This podcast was written by Annemarie Lewis, host of We Are Rivers. She is a college student at Colorado College and a river enthusiast. She started making podcasts about water conservation while in high school and plans on, “Living a life full of water conservation advocacy.” Her hobbies include backpacking, climbing, river running, and she is an amateur piano player. Read Annemarie’s river story here.

For this episode of We Are Rivers, we take a break from understanding the policies that manage and protect our rivers to focus on why it is we care about protecting rivers in the first place. In Episode 16 we hear from two of our listeners: Eliza Stein and Jordana Barack as they share their river stories. You might recall that we kicked off We Are Rivers in episode one, “The Value of Rivers,” with a discussion of the economic, spiritual, and environmental significance of rivers. Rewind to Episode 1 for further introspection as to why rivers are so incredibly important to all of us across the country.

Eliza Stein and Jordana Barack are both whitewater rafters with strong passions for rivers and the power they hold. Their appreciation of rivers is the central thread tying their stories together as they, like each of us, have different backgrounds and life experiences. Eliza recently graduated college, where she learned how to raft, and is currently working both as an EMT and at the “Mountain Chalet” outdoors store in Colorado Springs, CO. Jordana’s career has long been intertwined with water; for the last 8 years she has worked for New Belgium Brewing, a company’s whose core product intrinsically depends upon a robust supply of clean, safe, reliable drinking water. She started behind the bar telling the story of New Belgium and today is the Brewery’s corporate secretary. Despite their different stages in life, Eliza and Jordana both gravitate to the same space for emotional fulfillment: wild, free-flowing rivers.

Rivers attract all sorts of people, whether you live in a dense urban area or smaller rural community. Almost every American lives within a mile of a river or stream – and rivers do in fact connect us all. Some of us have the opportunity to spend multiple days on wild, remote rivers, others ride or drive over or next to rivers on their way to work or school, while others see rivers as their livelihood. Regardless of how rivers are experienced, it’s vital that we all share our stories of connection and appreciation for them.

Unfortunately, not everyone is able to experience wild and remote rivers. River running can be an expensive sport that often requires significant time to explore, particularly those reaches far from the beaten path. For those of us lucky enough to experience them firsthand, we have a responsibility to tell our stories, to attend water conservation meetings, and to help others experience the power of rivers in whatever way that may be. If not us, who?

I myself got involved with rivers through my high school geology teacher, who doubled as a world class kayaker. He took me under his wing and taught me how to kayak. Ironically enough, I was absolutely terrified of being in water before he encouraged me to bite my fear. The first time I got in his boat, I was in a pool not more than four feet deep in Glenwood Springs, Colorado. “Are you ready?” He asked. I nervously nodded my head, tightly squeezed my eyes shut, and plugged my nose. A final whimper emerged, and then I was submerged. He flipped the kayak over with me in it so that I could feel what it was like to be upside down in a boat, a dark, oxygen deprived place. When I resurfaced, I looked at him for a moment and then embarrassingly started bawling.

In that moment, you couldn’t have convinced me that within a month, I would be paddling 90 miles down the San Juan river with him and a group of classmates who were also beginning their lives on the river, or that I would run a podcast series about rivers and water conservation through American Rivers. And yet, here I am. My mentor flipped me over a dozen more times that day, dealing with my cranky mood, and eventually the dark oxygen deprived place wasn’t so scary anymore.

The moral of the story is this: had he not enabled me with his gear and enthusiasm, and told me all about the problems facing rivers, this podcast series wouldn’t exist, and everything you’ve enjoyed about it would be “poof!” Change starts with a story, a mentor, and deep breath, and it grows. It is our responsibility as river runners to tell our stories, to show up, and to enable our sport to reach a more diverse group of people. I’m excited to share my most memorable river memory with you as a part of American Rivers’ 5,000 Miles of Wild effort. Check it out here.

The stories of how Eliza Stein and Jordana Barrack became involved in river running, their favorite memories on water, and what they hope to accomplish with water conservation and inclusivity will be featured in this episode, so I encourage you to listen in. Stories have the power to emotionally relate people to issues and causes, and this relation creates solidarity, this solidarity fosters cooperation, and this cooperation leads to conservation.

Join us by listening to Episode 16 of We Are Rivers, The Power of a Story. After you’re done, take a moment and share your story with us as part of our 5,000 Miles of Wild story collection.

The Clean Water Act’s path toward protecting our waters has many twists, turns, and apparent dead ends. The law’s treatment of stormwater– the polluted and untreated rain and snowmelt that runs off of streets and parking lots into our creeks and rivers – is one of the convoluted chapters. Some thirty years ago, Congress amended the Act to begin reining in this most widespread of pollution sources. Urban areas, in particular, were required to develop stormwater management programs to reduce future discharges, particularly those from municipal operations and from new development projects. These programs have had many successes, but still struggle to adequately restore and protect our urban waters.

In large part, the difficulties in reducing urban stormwater pollution stem from the way the Clean Water Act has been implemented by the EPA. The permit programs administered by the Agency and its state partners generally do nothing to get at the real source of the stormwater problem – the vast acreages of concrete, asphalt and rooftop that already dominate urban watershed. Owners or operators of existing “impervious areas,” as they’re called, are almost never required to take on-site steps to reduce runoff. This creates huge inequities in efforts to prevent stormwater pollution: new property developers must take costly steps to control runoff, and the strained budgets of municipal agencies are forced to bear the expense of controlling pollution from exiting parking lots, businesses, and institutions. Meanwhile, our waters are slow to heal.

The ramp to Interstate 95 over the Middle Branch Patapsco River | Photo by Famartin

In 2015 American Rivers and its partners Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), Los Angeles Waterkeeper, and Blue Water Baltimore sought to change this. We filed a series of petitions with the EPA requesting that they follow the law, and require that owners of certain impervious areas obtain stormwater permits where their runoff causes or significantly contributes to water quality impairments. The EPA rejected those requests, even as they acknowledged that these areas were the source of serious water pollution. In an effort to hold the Agency accountable, we took the Agency to court, challenging decisions it made to reject our efforts to protect the Dominguez Channel in Long Beach, CA and the Back River, near Baltimore, MD. In August 2018, we won our first case, in the Central District of California. Just last Friday, we won the second, when the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland ruled in our favor. As a result of these twin victories, EPA’s efforts to turn away from these permanent pollution sources, and to count on ineffectual local stormwater programs, have been soundly rejected.

Going forward, we have the responsibility of making sure that the EPA, its regional administrators, and state agency partners respond diligently, and commit to meaningful measures to reduce stormwater from large commercial, industrial and institutional properties that discharge harmful pollutants to our waters. Fifty years after the passage of the Clean Water Act, Americans in cities across the country, large and small, deserve to the promise they were made in 1972 – to have waters that are fishable, and swimmable, and healthy enough for all Americans to enjoy.

Dr. Mack Dallas was born in Upson County, Georgia in 1933, in a community where the landscape and culture are dominated by the upper Flint River. People in his hometown of Thomaston went to the river to get cool in the summer, to hang out on the weekend, to fish the river’s big shoals for hard-fighting shoal bass, to float past Sprewell Bluff… to be out in nature was easy: the river has always been the place.

Back in 2012, when I’d just started working on conservation issues on the Flint, Dr. Dallas told me why his experiences with the river and his community led him to join Flint Riverkeeper’s founding board in 2008: he had witnessed the river, the community’s lifeblood for as long as he could remember, drying up before his eyes.

“You could walk across it in your Sunday shoes without them getting wet,” he told me.

He was referring to three drought events starting in 2000, in which the great river Dr. Dallas and his neighbors knew had turned to a trickle. Each dry spell resulted in flows in the upper Flint running 30 to 50 percent lower than anything Dr. Dallas would have witnessed in the 20th century—even during the driest times. There have been four droughts in the 21st century here, with a nasty one in 2016 that thankfully was short-lived.

Potato Creek, Flint River Basin | Photo by Alan Cressler

Dr. Dallas has since passed away, but my conversation with him early in my work on how American Rivers could address low flows on the upper Flint has stuck with me.

The Flint River’s headwaters spring up just north of Atlanta’s international airport and flow to the Fall Line of central Georgia between Macon and Columbus. Arguably more than on any river in the Southeast—or even the eastern United States—the 21st century has found the upper Flint suffering dramatic and relatively sudden strains of water scarcity. Because of this, American Rivers has identified it as a good place to dig deeper into a collaborative approach to addressing water supply issues.

In 2013, American Rivers convened a collaborative forum called the Upper Flint River Working Group, which brought together partners in the basin to envision a river system healthy enough to maintain the various social, ecological, recreational and economic benefits the Flint River system provides: water supply, recreation, fisheries, property values and a healthy river ecosystem, to name a few. The working group is a voluntary collaborative made up of the staff leadership of all the large water utilities in the upper basin, local conservationists, non-profit conservation organizations, and sustainability staff of Atlanta’s international airport.

This spring, after five and a half years of working together, we’ve published Ensuring Water Security for People and Nature, a report outlining the Working Group’s progress and how we’ve made inroads into communicating across agencies and interest groups in order to address water security and drought resilience in the basin, both for the ecology of the river and the communities that depend on the river for water supply, fisheries, recreation and more.

The report looks back at the five-year history of the group itself, at the dialogue and collaboration that have led to specific achievements and successes. It captures the group’s consensus-based for managing the river system in the future. And, it details the future plans of the working group: to continue improving management actions for water availability and to collaborate with more river stakeholders and with scientists researching the upper Flint, who can assist in understanding water needs in the basin.

Shoals Spider-Lilies | Photo by Alan Cressler

Ultimately, lasting solutions to the regional effects of global climate change, urbanization and the myriad other threats facing our nation’s river systems must be tackled at the local level. Water managers, scientists, activists and people like Dr. Dallas who understand the river’s history and local significance, must identify and respond to the pressures posed to the river, for the benefit of people and ecology.

I hope our ways of addressing water scarcity in the Flint can help as the same challenges begin to strike more and more parts of the country. Meanwhile, here in the Georgia Piedmont, we hope to be more prepared for the next drought, whenever it arrives.

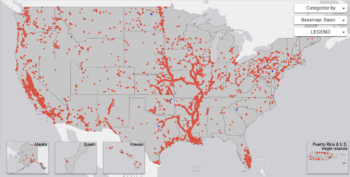

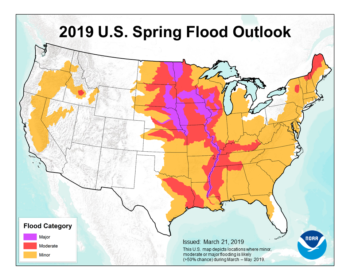

We’ve all been watching the dramatic footage of flooding in the Midwest, destroying homes, fields of crops, infrastructure and even air force stations. The scale of the damage is daunting and it can be hard to wrap our heads around the scope of change that is needed in order to avoid such catastrophic damage in the future. In the coming weeks and months, the communities and landowners across the Midwest will want to act as quickly as possible to get back on their feet. A key step will be deciding whether to rebuild back the way things were, or to choose new options that could make us more prepared for the next flood.

There’s a famous quote by Gilbert White, the founder of the floodplain management movement: “Floods are an act of God; flood damages result from the acts of man.” The rain will always fall, but the decisions we make about how we manage our rivers and use our floodplains determines how extensive the damages are during a flood.

The rivers across the Midwest, and much of the country have been dramatically altered from their natural states over the last century. Before Europeans settled in the Midwest, big rivers like the Missouri and Mississippi would spread their flood waters out across wide floodplains, slowing the flows, and rejuvenating robust floodplain habitats. As farmers sought to make their land tillable, they straightened streams and created extensive levee systems to keep flood water off their land and in the streams. About a century ago, the Army Corps became the official flood control agency of the United States building monster levee systems along our big rivers. At last count, they oversee almost 30,000 miles of levees across the United States.

As shown in this excellent piece by Propublica, relying on levees can have unfortunate consequences. Levees create the illusion of safety, and the “protected” floodplain can be attractive places for people to build communities and businesses. But trapping flood waters in a narrow channel forces water to move downstream more quickly, which puts stress on levees. When floodwaters overtop or breach a levee, the results can be catastrophic to the communities and fields behind it. To make matters worse, when levees fail, it tends to happen at the same spots meaning we see a damage and repair cycle play out flood after flood.

In many areas across the country where a historic reliance on levees has led to increased flood risk, communities and landowners are choosing to reduce the risk of future levee failures by creating more room for flood waters to spread out across the floodplain. These natural flood management approaches to alter levee systems and make room for rivers to flood can come in many forms.

- After the 2011 Missouri River floods, a flooded landowner was tired of having his levee fail during floods, and asked the Army Corps to do a levee setback rather than rebuild it back along the river.

- In 2010, the Army Corps worked with Iowa Department of Natural Resources to acquire the 300 acres of floodplain land and transfer it to the Green Island Wildlife Management after a repetitively damaged levee breached on the Maquoketa River in Iowa.

- In Yakima County, Washington, after repetitive damage to their levee system, the flood control district is proactively reconnecting the Yakima River to the floodplain to reduce future flood damage.

Each of these projects reconnected the river with the floodplain and reduced flood risk. But they had another thing in common — they were implemented after levees were damaged by a flood. Unfortunately, examples like these are few and far between. After a flood, there’s pressure to rebuild levees as fast as possible, to be ready before the next flood hits. Unless an alternate solution has been identified and planned ahead of time, there may not be time to plan a levee setback or get landowners on board with an acquisition or new idea.

After the 2011 Missouri River flood, the Omaha district of the Army Corps explored levee setbacks, and potential to implement projects after a flood. River managers across the Midwest should build upon their past success and planning to implement projects that give the river additional room to flood whenever they are repairing damaged levees. We need to work as quickly as possible with landowners and other stakeholders to identify opportunities to create more room for rivers to flood within the existing flood control system.

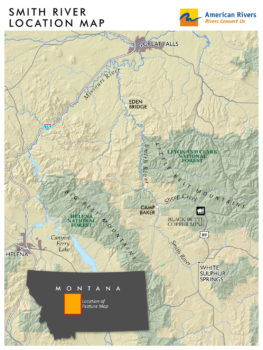

For those of us who love rivers and call Montana home, March is the time of year when hope springs eternal. Not just because the sunshine comes with newfound warmth and the deep snows of winter finally begin to melt, but also because it’s when we find out if we won a permit to float the Smith River – Montana’s only permitted river.

For the 19th consecutive year when I checked my drawing status, I was greeted with the dreaded word, “unsuccessful.” Fortunately, I have lots of friends who also put in for Smith River permits, and one of the lucky ones already has invited me on a trip this fall.

That’s the good news.

The bad news is a proposed underground copper mine along Sheep Creek in the Smith River’s headwaters took a big step forward when the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) released a draft environmental impact statement (EIS) on March 11. Despite the fact that the so-called Black Butte copper mine would be located in the Smith’s headwaters and the rock in which the copper ore is located is highly prone to creating acid mine drainage, the DEIS concluded the mine would have “no impact to water quality, air quality or aquatic resources.”

A harmless mine. Talk about an oxymoron.

The Montana DEQ’s conclusion stands in stark contrast to what our own expert mining consultants have told us. In a guest blog published in August 2016, Tyler Shepherd, who spent his entire professional career in the mining industry, wrote that the Black Butte copper mine would “irreparably contaminate the Smith River.”

The copper mine is being proposed by Sandfire Resources America, a subsidiary of Perth, Australia based Sandfire Resources. It would be located on 1,888 acres of leased private ranch lands adjacent to and underneath Sheep Creek, the most important trout spawning tributary in the entire Smith River system. The mine site is located about 19 miles upstream from Sheep Creek’s confluence with the Smith River. Since Sheep Creek moves along at about four miles per hour, that means any mining pollutants would reach the Smith River in less than five hours.

So, when Sandfire says there’s no need to worry about the mine impacting the Smith River because it’s almost 20 miles away, call me cynical.

Now that the draft EIS has been released, the public has until May 10 to submit written comments. The Montana DEQ will host at least two public meetings at which they will present information and take public comment – in Livingston on April 29, and in White Sulphur Springs on April 30. We are urging to the DEQ to hold at least two additional public meetings, one each in Helena and Great Falls.

American Rivers and our partners have hired a team of expert consultants in the fields of hydrology, geochemistry, fisheries biology and environmental law to carefully pour over the draft EIS to determine if it has any fatal flaws. As soon as our team finishes its review, we will draft our written comments and send action alerts to our members and activists so you can submit your own informed comments on the proposed mine.

How you can help protect the Smith

If you would like to receive our action alerts on the proposed Black Butte copper mine later next month, please sign up here. During the scoping phase of the EIS, American Rivers generated more than 8,000 public comments. Now that the draft EIS has been released, we’ve set a goal of generating 20,000 comments opposing this dangerous mine.

World Recycling Day is March 18th and today we are not only celebrating this “recycled” holiday, but also kicking off the 2019 National River Cleanup® season. March is when the weather (usually) starts to warm, and thousands of volunteers from Maine to Alaska begin exiting their homes to participate in local river cleanups.

Every year, cleanup volunteers find thousands and thousands of plastic bottles and bags. In fact, plastic containers are in the top 5 most common trash items found at river cleanups. Plastic litter takes up to 1,000 years to naturally break down into microplastics.

We live in a plastic world. And let’s be honest, trying to live 100% plastic-free right now can be very difficult, if not impossible.

ORSANCO’s Ohio River Sweep | Photo by Lisa Cochran

So what can you do? Integrating the 5 R’s (Refuse, Reduce, Reuse, Repurpose, Recycling) into your everyday lifestyle is the first step. By refusing and reducing your plastic product purchases and uses, you will make a huge impact. Even if you can’t achieve the first 4 R’s, then your best option is to recycle these items. Think of it this way: the less plastic you use or the more you recycle, the less likely it will end up in our nation’s waterways. And of course, you can also organize or volunteer at a river cleanup!

Thankfully, the overuse of plastics is finally being addressed. Maryland announced a ban on Styrofoam food containers becoming the first state to do so; Cities across the country have banned plastic straws from restaurants and/or businesses; and after 100,000 people signed a petition, Trader Joe’s pledged to switch from plastic produce bags to compostable ones. As we take action locally and nationwide, the power of consumers and communities has never been greater.

When cleanup volunteers begin finding less plastic pollution in their communities, we’ll know we’re on the road to achieving success and having plastic-free rivers!

Join us in celebrating World Recycling Day:

- Take the pledge to pick up trash before it enters your river or creek

- Participate in the viral ‘Trashtag Challenge’ that has been taking over social media. We dare you to take a photo before and after of an area that needs cleaning. Once you’ve finished cleaning, post the pictures on social media with the hashtags #trashtag and #rivercleanup.

- Organize a cleanup with National River Cleanup®, or volunteer for an existing cleanup near you

“If there is a point to being in the canyon, it is not to rush but to linger, suspended in a blue-and-amber haze of in-between-ness, for as long as one possibly can. To float, to drift, savoring the pulse of the river on its odyssey through the canyon, and above all, to postpone the unwelcome and distinctly unpleasant moment when one is forced to reemerge and reenter the world beyond the rim-that is the paramount goal.” ― Kevin Fedarko, The Emerald Mile: The Epic Story of the Fastest Ride in History Through the Heart of the Grand Canyon

Rigging boats at Lee’s Ferry | Photo by Caleb Roberts

I still remember the late-February evening in 2017, sipping a porter at my home in Brevard, North Carolina, when I opened my e-mail to find a new arrival to my inbox with the subject line “You have won a Grand Canyon River Launch Date.” This message from the National Park Service thanked me for submitting an application for a 2018 launch and notified me that, if I desired, myself and 15 companions could journey into the Grand Canyon the following fall. Needless to say, I was ecstatic. A few months earlier, a few friends and I decided to apply for a weighted lottery permit to raft the Grand Canyon in the autumn of 2018. Of the collectively-applied-for 30 dates, we pulled two permits. I pulled one for November 17th, and our friend Emory succeeded with a Thanksgiving Day launch date. We ended up choosing to use Emory’s permit, and upon confirming with the National Park Service, our dreaming shifted to planning; we were heading to Lee’s Ferry in less than two years!

The team at Lee’s Ferry | Photo by Caleb Roberts

The following year-and-a-half was a whirlwind. We expanded our group to 16 river runners; 9 ladies and 7 men, hailing from California, Montana, Colorado, North Carolina, and Canada. Most people only knew a few others at the time, but fantasies of the Canyon and trip planning over group messages started to pull the new friends together. 21 months later, after endless planning, permitting, gear-wrangling and renting, money exchanges, transportation logistics, team member changes and miles traveled… amazingly, we were all in Arizona, sprawled across the floor of my friend Anona’s home in downtown Flagstaff. Sleeping pads were strewn about, last minute gear-checks and casual conversation filled the room, and a general sense of excitement buzzed about. We were heading to Lee’s Ferry the following morning with our outfitter, Ceiba Adventures, from whom we had rented 6 oar rigs, along with food and cooking supplies for our upcoming 24-day and 277-mile journey down the Colorado’s deepest canyon. We were anxious, stoked, nervous but generally delighted to be finally leaving the civilized world for a few weeks, and solely focused on traveling downstream through a wonderland of whitewater, geology and culture.

Our collective pushed off from our camp at Lee’s Ferry the following morning to a warm breeze and beautiful sunshine. As the Grand Canyon National Park ranger told us the evening prior, we had only one appointment in the next 24 days; to be at Pierce Ferry by the morning of December 15th. When else in our lives had we only one appointment in the next 3 ½ weeks? As Kevin Fedarko says in his book, The Emerald Mile, “If there is a point to being in the canyon, it is not to rush but to linger, suspended in a blue-and-amber haze of in-between-ness, for as long as one possibly can.” We had a long way to go and plenty of time to get there.

Blasting through the lower hole in the notorious Crystal Rapid | Photo by Jack Henderson

The next 277 miles would test us physically, mentally and spiritually, but we would also find many lessons and gifts between the stone walls, rushing waters and open sky. Towering waves and sticky hydraulics would grapple with our control of the rafts, strong eddy lines would attempt to push our vessels off course, sandy winds would disrupt evening sleep, heavy midnight rain would flood camp, and bitter chills would be cause for morning fires to ensure warmth. However, we would be pleasantly surprised by cozy afternoon sun, giggle to endless raft guide jokes, be inspired to learn about the geology of the Grand Canyon (Vishnu Schist, an intrusive igneous rock, is over 1.71 billion years old!), share laughter within a homemade camp sauna, rappel down side canyons, cook delicious meals over open fires, and cheer each other on as we rowed and kayaked through endless beautiful whitewater.

Running the strong line through Upset Rapid | Photo by Jack Henderson

The journey through the Grand Canyon reaffirmed my own feelings that protection of open spaces and clean and plentiful water is vital to our nation’s health and longevity. A vague yet powerful sentiment arising from feeling small in large spaces. A floating morsel of adventurous attitude amongst an amphitheater of granite, sand and rushing river. The Grand Canyon and the Colorado River, although mighty and powerful, is an ironic wild space; a huge expanse of rugged natural landscape between two of the largest man-made nature-controlling devices in the United States.

I come from a background in natural resource management, outdoor recreation, water quality, stream restoration and self-propelled adventure travel, where wild spaces are sought and appreciated. Living in the southern Appalachians, I am no stranger to large hydropower projects on special rivers. The Tennessee, Little Tennessee, Pigeon, Ocoee and Savannah rivers are all restricted by impoundments for sake of generating electricity and flood control. The effects of these dams include dewatering of stream channels, restricting migration of fish and negatively fluctuating water temperatures.

Amongst it in Lava Falls | Photo by Jack Henderson

In Arizona, the Colorado River is impounded above the Grand Canyon by Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Powell, and below by Hoover Dam and Lake Mead. Historically, snow would melt from the Rocky Mountains in Colorado and springtime high-flow torrents would cascade down the Colorado River. This would form a liquid crescendo of momentum, gathering silt and sediment along its journey through Colorado, Utah and Arizona before rushing through the Grand Canyon as muddy brownish-red (where the name Colorado comes from). “Too thick to drink, and too thin to plow” has been used to describe many rivers within our nation, but it undoubtably pertained to the Colorado before the dams were in place. Since the gates were closed on Glen Canyon Dam in 1966, the silt and sediment traveling down the barren landscape between the Rockies and the Grand Canyon, now becomes trapped within Lake Powell, and thus the water released from Glen Canyon Dam runs a cold, clear green versus its historic muddy brown.

Happy crew below Serpentine Rapid | Photo by Jack Henderson

High flow releases occur sporadically to mimic these historical pulses, with the purpose of shifting sediment around the canyon; rebuilding sandbars, beaches, etc., yet the river runs colder and clearer on average than its pre-dam days. The reservoirs themselves are also becoming less efficient. As sediment builds up behind the dam, there are fewer acre-feet available for water storage. These negative impacts, combined with evaporation and lower volume inputs into Lake Powell are components of a dire situation in the southwest. Human alteration of the landscape and climate change have caused shortages of water for consumption, energy, agriculture and cleaning all across the arid southwest, and predictions for the future suggest worsening drought conditions and increasing human populations. Fortunately, the landscape between the dams, the Grand Canyon of the Colorado, is still protected and managed as a special wild space. Grand Canyon National Park is a product of many people’s dedication and enthusiasm towards conserving natural beauty, ecologically rare habitats and recreational opportunities. The National Park Service does a fantastic job of managing a wilderness experience for boaters between the rims.

Looking downstream from Nankoweap upon an emerald green Colorado River | Photo by Jack Henderson

24 days after our first moments together at Lee’s Ferry, our crew docked our rafts at Pierce Ferry under an open sky on Lake Mead. We were exhausted, but our hearts were full. 3 ½ weeks away from the ‘real world’ brought our focus back to the important themes of life; community, hard work, laughter, good food, the natural world and love. Trips like these not only recharge our bodies and minds, but also can have a large impact on our interest and inspiration towards conserving and protecting the places that just brought us so much adventurous joy. I encourage everyone to spend time on rivers; whether it be 277 miles through northern Arizona’s Grand Canyon, or even just a few moments in a canoe on a neighborhood pond.

Rafts and kayaks along Tequila Beach below Lava Falls | Photo by Jack Henderson

This is a guest blog by Dakota Goodman and Gregory Fitz.

In October 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act into law. The legislation had been sponsored in Congress by Senator Frank Church of Idaho. The National Wild and Scenic Rivers system was conceived around the remarkable idea that some rivers were so valuable to the cultural and environmental legacy of a region that they, and some of their surrounding area, should be preserved as natural, free-flowing waterways for the benefit and enjoyment of future generations. Since then, almost 13,000 miles of 208 rivers across the country have been protected. Six of those rivers are in Washington.

To celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, we’re going to spend some time over the course the year telling the stories of Washington’s designated rivers: Illabot Creek, the Klickitat River, the Pratt River, the Skagit River, the White Salmon River and the Middle Fork of the Snoqualmie River. Each is a unique part of Washington’s astounding network of rivers and each earned its designation in the national system through the hard work and foresight of advocates.

In this final installment of our series, we’ll take a closer look at the Middle Fork Snoqualmie River and Pratt River, in Washington’s North Cascades.

The Middle Fork Snoqualmie River and Pratt River

Middle Fork Snoqualmie River Bridge | Photo by Monty VanderBilt

The Middle Fork Snoqualmie River begins at Chains Lakes in Washington’s Alpine Lakes Wilderness Area. From there it flows south to Williams Lake, then runs until it joins the North Fork Snoqualmie River near the City of North Bend. The South Fork Snoqualmie joins soon after and together they form the main stem Snoqualmie River. The Middle Fork Snoqualmie flows almost 41 miles long and has a single major waterfall, Nellie Falls, which is 150-feet tall. Along this route in the upper river valley, the major tributaries of the Taylor River and Pratt River add significant volume to the Middle Fork. Eventually, the Snoqualmie and Skykomish Rivers join to form the Snohomish River, which empties into Puget Sound at Everett.

The Snoqualmie River takes is name for the Snoqualmie People, (Sduk-al-bixw) a Coast Salish Native American people whose ancestral home included the Snoqualmie Valley. A federally recognized treaty tribe, many Snoqualmie members still live and work in the region and rely on the surrounding national forests for subsistence harvest.

The Pratt River begins as a tiny creek when it drains from Upper Melakwa Lake. From there it flows into the larger Melakwa Lake and continues almost 10 miles to the confluence with the Middle Fork of the Snoqualmie River. It is named for George A. Pratt, a prospector of European descent who discovered iron deposits in the area in 1887.

National Wild and Scenic Rivers Designation

The Middle Fork of the Snoqualmie River and the Pratt River were both designated as Wild and Scenic in December of 2014. They were included in a package of public lands bills that was attached to the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act and signed into law by President Obama. In Washington, the bill expanded the Alpine Lakes Wilderness by 22,000 acres and protected 27.4 miles of the Middle Fork of the Snoqualmie River and 9.5 miles of the Pratt River within the Wild and Scenic River System. Included in this legislation was 14 miles of Illabot Creek, which we profiled in our last post in this series.

Fly fisher on the Snoqualmie | Photo by Monty VanderBilt

Like many rivers throughout the country, the Middle Fork Snoqualmie and Pratt’s Wild and Scenic designation was the result of many years of dedication on the part of river and wilderness advocates. The rivers flow through an area of immense rain and snowfall and are prone to dramatic flooding. Dams had often been proposed and remained a contentious issue in the Snoqualmie valley, despite the widespread regional appreciation for the undeveloped nature of the watershed. As early as 1990, the U.S Forest Service had recommended the Middle Fork Snoqualmie and Pratt Rivers as eligible for Wild and Scenic designation based on their “outstanding, regionally significant recreation, fisheries, wildlife, geological and ecological values.”

It took years for that recommendation to be acted upon, but in August of 2007, Representative Dave Reichert and King County Executive Ron Sims, and others, announced a proposal to expand the Alpine Lakes Wilderness and include the Middle Fork Snoqualmie and the Pratt Rivers in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Unfortunately, the bill never came up for a vote in the 110th Congress.

The Middle Fork of the Snoqualmie River and Pratt River: Today

The Middle Fork Snoqualmie and the Pratt Rivers remain a pair of beloved, crucial Washington watersheds in a state rich with hundreds of beautiful river miles. They flow through a rugged valley only about hour outside of Seattle and are among the rivers most used by anglers, paddlers and whitewater rafters because of their proximity to the state’s major population center. Native cutthroat trout and whitefish thrive in these waters. Flowing from high, protected headwater lakes, both rivers contribute important clean water resources to the downstream communities and, eventually, the lower Snoqualmie and Snohomish Rivers. The valley hosts many hikers, boaters, anglers, and mountain bikers along vast networks of trails and the protected forests and riparian zones are exceptional habitat for all sorts of species, an especially important feature in an area slow close to a fast-growing city.

Pratt River valley | Photo by Monty VanderBilt

River Management Planning Process

Presently, the Forest Service is working on developing a Comprehensive River Management Plan (CRMP), a process required by the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act post-designation. They are gathering input from the public, tribes, and state and local agencies to inform this long-term management plan that is used to protect and enhance important values of the Middle Fork Snoqualmie and Pratt Wild and Scenic Rivers of the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest. The CRMP will provide guidelines for the river and land management and identifies the ways in which the Forest Service will protect and enhance the Wild and Scenic Rivers’ free flowing condition, water quality, and “outstandingly remarkable values.”

For more information on the planning process or to provide input during the river assessment, please visit tinyurl.com/MidForkSnoqualmie. The Forest Service is accepting comments from now through March 15, 2019.

In celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, we have teamed up with a number of partners and outdoor gear companies to collect 5,000 wild-river stories and to protect 5,000 more miles of such rivers nationwide. Share your story and learn more.

On February 14, the Trump Administration published a proposed federal rule that would roll back protection for streams and wetlands across the United States. But we don’t have this accept this awful valentine — Write to the Administration today and let them know that you support healthy rivers and clean water. Urge the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the Corps) to abandon this “Dirty Water Rule.”

The story behind this rule is a little complicated. Here’s the background:

The extent of the jurisdiction of the Clean Water Act (the Act) over the nation’s waters has been contested almost since the Act was passed into law in 1972. Opponents of the Act – associations purporting to represent developers, agricultural interests, and industry groups – seek to narrow the Act’s application, leaving as many of the nation’s streams and wetlands as possible beyond the law’s reach. Conversely, champions of rivers, wetlands and clean water – like your friends at American Rivers – argue that the Act’s call to protect the “waters of the United States” extends to the small streams and isolated wetlands that are so vital to clean water and the health of freshwater ecosystems. After all, we can’t adequately protect the waters of the U.S. if we ignore the small streams and wetlands from which they spring.

San Pedro River | Photo by Steve Sprager

After two convoluted Supreme Court rulings created tremendous uncertainty about the extent of the Act’s reach, the Obama Administration engaged in a lengthy rulemaking process to clarify the authority of the Act to protect small streams and wetlands that are so important to river health and contribute to the drinking water supplies of one in three Americans. Following years of painstaking scientific, economic and legal analysis, hundreds of public meetings, and a comment period that produced over a million comments, the “Clean Water Rule” was adopted, reaffirming the Act’s broad authority. Shortly after taking office, President Trump and then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt launched an effort to sweep away this carefully crafted rule and once again expose hundreds of thousands of miles of small streams and wetlands to unregulated pollution and degradation.

The latest salvo in this effort is the new Dirty Water Rule proposed on Valentine’s Day. The proposed rule would strip the Act’s protection from ephemeral streams (those that flow only a short time after heavy rain and snowmelt) that are particularly important to fragile freshwater ecosystems in the desert Southwest and other arid parts of the country. Moreover, the proposed rule would throw into doubt the Act’s protection of intermittent streams, those that run only at certain times of the year.

Wetlands with no apparent surface connection to other nearby water bodies would lose protection as well. This would abandon decades of previous regulatory practice and potentially expose up to half of the nation’s wetlands to pollution and degradation unrestrained by the Act, including prairie potholes, vernal pools, coastal prairies, and other important natural features of the American landscape.

Warner Wetlands, Oregon | Photo by Greg Shine, BLM

In contrast to the existing Clean Water Rule, the rule proposed by the Trump Administration is unsupported by scientific evidence, was promulgated with little public input, and is being rushed through the rulemaking process with limited opportunity for public comment. That’s why it is so important that you make your voice heard right now. The comment period runs only until April 15.

American Rivers and other champions for clean water worked for many years to put the existing Clean Water Rule in place. Over one million comments supported that effort. Now we need a similar outpouring, this time in opposition to the Trump Administration’s Dirty Water Rule. Follow this link to an action alert and draft letter that you can use to submit your own comments on this ill-conceived rule.

Streams and wetlands are the cradles of rivers, helping to gather and deliver water downstream, preventing flooding, filtering pollution, and serving as nurseries for fish and wildlife. Though flows or surface connections may not be readily apparent, scientists, water managers, anglers, hunters, paddlers, and nature-lovers of all kinds know how important small streams and wetlands are to healthy river systems. Let’s make sure they’re protected. Send a letter today urging the EPA and the Corps to withdraw the proposed Dirty Water Rule.

This is a guest blog by Catherine Schoeffler Comeaux.

“Throw me something, Mister!” is the official cry of Mardi Gras parade watchers lining the streets of Lafayette, Louisiana begging for beads during the weeks of fun and foolishness leading up to Lent. Revelers go home with loads of plastic jewels but also leave the streets covered with discards and debris. Much of the abandoned lightweight litter drifts into storm drains that lead directly to the Bayou Vermilion.

The Bayou Vermilion winds 33 miles through Lafayette Parish. Paddlers take to the bayou as an intra-urban getaway, fishers enjoy angling for catfish along its banks, and boaters regularly buzz about on the calm waters. Once considered one of the nation’s most polluted rivers, today it is a cultural and economic asset thanks to restoration efforts; however, litter is still one of the insults the bayou continues to endure. The Mardi Gras parades, with their encouraged hurling of loose plastics, are a dependable contributor to the litter and waste that afflict the waterways. Two local Mardi Gras krewes, the social clubs who put on the parades, have started taking action to change the situation.

A proud krewe member | Photo by By Skyra Rideaux

The Krewe de Canailles (pronounced dah Kah-NYE), which means mischievous in Cajun French, has taken a fun, up-bayou approach to the recurring Mardi Gras runoff. By asking its members to replace plastic trinkets typically thrown with unique eco-throws handed to parade goers, the Krewe de Canailles is trying to stop the problem at its source. Paul Kieu, co-founder of the krewe, explains, “All of us in the krewe love canoeing, kayaking, and having fun on Louisiana waterways, and we see all sorts of plastic trash every time we drive past a coulee or up close while on the water. While we all love traditional style parades, we wanted to be unique in ours to minimize our impact on the streets. We encourage our marchers to hand their throws to the people on the street rather than throwing, in which case people often leave them on the ground.”

The Krewe of Rio has partnered with Lafayette Consolidated Government’s Project Front Yard initiative to pilot a new process for Mardi Gras parades. Volunteers help reduce waste by collecting cardboard and plastic packaging before the parade. The volunteers then follow the “last float” which gets loaded with discarded beads and litter in the wake of the festivities. In the past two years, aided by the bags provided by American Rivers, 55 volunteers collected 700 pounds of plastic film, 10,140 pounds of beads, and thousands of pounds of cardboard for recycling and reuse.

Mardi Gras attracts visitors from all over the country to passé un bon temps, and Mayor-President Joel Robideaux’s goal is to make a great first impression. “Lafayette presents a family-friendly Mardi Gras experience to parade-goers every year. We want to continue the tradition of showcasing our food, music, and culture to visitors during the season, while also being mindful of what we leave behind after the festivities are concluded. This partnership [with Krewe of Rio] is an excellent way to highlight our community’s commitment to the beautification of our city.”

The success of these efforts has caused many other krewes to ask the question, “What can we do to make Mardi Gras cleaner?” Thanks to American Rivers for being a part of this movement to nudge the traditions of Mardi Gras in cleaner greener direction so that preventing excess waste and litter becomes the standard practice of Lafayette’s Mardi Gras celebration.

—

The day after Mardi Gras, Lent arrives and springtime cleanup efforts begin with opportunities to reflect on how we as a community can better reduce our waste and control litter. The University of Louisiana at Lafayette will encourage community members and students to participate in The Big Event on March 30th when hundreds of volunteers will clean at bayou side parks and along coulees. The following week, Lafayette Consolidated Government in partnership with the Bayou Vermilion District will host their 35th annual Trash Bash when paddlers and boaters will be on the water removing litter.

For more information about the history of the Bayou Vermilion, paddle trail maps and upcoming bayou related events, visit www.bayouvermiliondistrict.org.

Catherine Schoeffler Comeaux is a Recycling Clerk for Lafayette Consolidated Government. She also serves on the Bayou Vermilion District Board of Commissioners.

Although 2018 has passed, we are still celebrating National River Cleanup®’s successes! In 2018, National River Cleanup registered cleanups at 3,166 sites, mobilized 57,228 volunteers and removed almost 2,000,000 pounds of trash.

Volunteer with bowling ball | Christina River, DE | Photo by Joe Butera

While cleaning up waterways and communities, volunteers were busy picking up usual items such as water bottles and tires, but this year was a little different. Volunteers in 2018 found some unique and, at times, bizarre findings. Here are a select few:

- Plastic raven statue

- Mannequin head

- Bowling ball and… a disco ball

- Blow torch

- Cash register

- 15 unmatched sandals

- Washing machine

Cleanup organizers and volunteers spend a lot of time outside getting dirty, but it’s important to recognize the time and effort it takes before that to plan a successful event (approximately 10 hours for an average size cleanup). For larger cleanups, it takes much longer. Organizing a cleanup takes determination and dedication.

National River Cleanup is proud to work with cleanup organizers and volunteers nationwide to help make their cleanups even more successful and protect waterways near and dear to our hearts!

In 2016, we launched the National River Cleanup Champions program to shine a light on cleanup organizers and all the great work taking place across the country. The categories for the 2018 awards are:

- Most River Miles Cleaned

- Most Pounds of Trash Collected

- Most Volunteers Mobilized

- Tiny but Mighty

- Cleanup to Watch

Want more?

Check out what some of the National River Cleanup organizers had to say:

Great Los Angeles River Cleanup | Photo by William Freas

Friends of Los Angeles River (FOLAR): “We are thrilled to be recognized by National River Cleanup as the 2018 Cleanup Champion for mobilizing the most volunteers. Our Great LA River Cleanup is 30 years old this year, which promises to be our biggest and most impactful yet. Over the years we’ve mobilized over 55,000 people to remove a cumulative 500 tons of trash. This is a true display of River stewardship and the power of community.”

Amigos Bravos: “Taos County River and Lands Clean Up is a strong community collaboration removing at least 2 tons/year for the last 12 years. Organizational leaders include: Rocky Mountain Youth Corp (AmeriCorps), lends many youth to the effort and their organizational prowess; Amigos Bravos, a state-wide water conservation NGO who helps to organize the effort, gather supplies and promote the cleanup; the Taos County Solid Waste Disposal provides heavy equipment, large dumpsters and volunteers; and the Forest Service, Camino Real Ranger District provides vehicles, equipment, and site location identification. Numerous other community members and organizations also support this trash removal effort. Taos is plagued with illegal dumping sites and we are proud to work towards a cleaner future for our County’s forests, waterways, and inhabitants.”

Uncompahgre Watershed Partnership: “Tiny but mighty? Hoo-ray for the Uncompahgre Watershed Partnership, Ouray Ice Park and the clean-up crew! One reason for the amazing weight of debris collected is that it hadn’t been done before, so there was a lot of heavy old junk in there. But it sure was great to get it out, and when I climb in the gorge, I smile, thinking about our efforts during our inaugural Love Your Gorge event.” – John Hulburd”

Boardman River Clean Sweep | Photo by Norm Fred

Boardman River Clean Sweep: “The Boardman River Clean Sweep started 15 years ago as a one-time cleanup on the Boardman River in Traverse City, MI. We invited our entire paddle club and expected 8 or 10 to arrive, but 80 excited paddlers showed up. Now we clean 21 rivers, and multiple illegal dumping sites along our rivers and tributaries. We have fostered 14 other organizations who now clean their local rivers with our help.”

CT River Conservancy: “For 22 years, CRC volunteers have gotten their hands dirty and feet wet for cleaner rivers. Less trash is being found in the Connecticut River and tributary streams. But single-use plastics like plastic bags or beverage bottles, as well as dumped tires and Styrofoam have been persistent. CRC’s Source to Sea Cleanup goes beyond cleaning up tons of trash. Thousands of volunteers leave the cleanup fired up to make more of a difference. They join us in taking action to pressure our government leaders, businesses, and manufactures to “Stop Trash Before It Starts” by passing laws that reduce trash and improve recycling, voluntarily offering better options to consumers, and taking responsibility for manufactured products from creation through use and reuse. Our volunteers’ are helping overhaul the larger trash system!”

Thornapple River Watershed Council: “Organizing is easy when there are experienced dedicated participants willing to help rain or shine. The Council and Barry Conservation District have been doing this joint cleanup for more than 20 years with the support of volunteers, sponsors and organizers. A few years ago, we started using an online registration process which helped organize who wanted to go where allowing us to steer resources and maximize our efforts. Each year offers some unique finds from 100’s of tires to large screen TV’s. In recent years, the trash yield has been low and the health of our tributary is good due to our efforts and the efforts of local municipalities, canoe liveries, riparian owners and educational instructions.”

Thank you to all National River Cleanup organizers for being champions of our rivers!

- Organize a cleanup with National River Cleanup®, or sign up for an existing cleanup near you

- Learn more about recycling with our National River Cleanup® recycling guide

- Take our River Cleanup Pledge to pick up trash and help us fill our virtual landfill

- And more!

It’s celebration time. Today, the U.S. house passed a landmark, bipartisan bill protecting more than 600 miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers and other public lands and waters nationwide.

“This is the biggest advancement for river protection that we’ve seen in nearly a decade,” said Bob Irvin, President and CEO of American Rivers.

S. 47, which the Senate passed earlier this month by a vote of 92-8, forever safeguards beloved rivers from Massachusetts to California from new dams and other harmful development. It’s a fitting celebration as the nation marks the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

The bill adds the following stretches of river to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System:

- 256 miles of the Rogue, Molalla, Nestucca, and Elk rivers in Oregon

- 110 miles of the Wood-Pawcatuck rivers in Rhode Island and Connecticut

- 76 miles of Amargosa River, Deep Creek, Surprise Canyon and other desert streams in California

- 63 miles of the Green River in Utah

- 62 miles of the Farmington River and Salmon Brook in Connecticut

- 52.8 miles of the Nashua, Squannacook and Nissitissit rivers in Massachusetts and New Hampshire

The bill includes other critical river protection and restoration measures, including:

- Authorization of the Initial Development Phase of the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan, a long-term climate adaptation, water supply reliability, river restoration and lands management plan for farms, fish and people in Washington state.

- Reauthorization of the Land and Water Conservation Fund, the nation’s largest and most important conservation program that provides hundreds of millions of dollars annually to secure the purchase and protection of public lands.

- Creation of the Frank and Jeanne Moore Wild Steelhead Sanctuary, protecting steelhead habitat in Oregon’s North Umpqua River watershed in honor of Frank Moore, a World War II veteran and his wife, Jeanne, beloved stewards of the river.

- Mineral withdrawals to protect the Yellowstone River in Montana, the Methow River in Washington and the Wild and Scenic Chetco River in Oregon from harmful mining.

- The long-overdue name change for Oregon’s Wild and Scenic Whychus Creek.

American Rivers President Bob Irvin praised Rep. Grijalva and Rep. Bishop, the Chairman and Ranking Member of the House Natural Resources Committee, for their commitment and leadership in championing the bipartisan legislation.

“Clean, free-flowing rivers are vital for our drinking water supplies, local economies and the outdoor recreation industry. We urge the President to sign this bill into law,” Irvin said.

The legislation is the result of years of hard work by local communities, businesses and advocates including the Nashua River Watershed Association, American Whitewater, the Farmington River Watershed Association, Molalla River Alliance, and K.S. Wild.

Along with the designation of East Rosebud Creek in 2018, Montana’s first new Wild and Scenic River in 42 years, today’s action is a major step forward for the 5,000 Miles of Wild® campaign, an effort led by American Rivers and American Whitewater, with support from NRS, OARS, YETI, REI, Nite Ize, Keen Footwear, Yakima, Kokatat, Chaco and other partners to protect 5,000 additional river miles and one million acres of riverside by October 2020.

To everyone who spoke up, attended a meeting, shared their story, called their member of Congress: thank you. Your voices matter, and when we speak up for rivers we all win.

Cheers to 620 miles. Cheers to new Wild and Scenic Rivers. Cheers to you, our supporters, who made this victory possible!