On June 13, the U.S. Forest Service initiated a regulation change that if successful would eliminate current public participation and reduce the role of science in the vast majority of land management decisions for the nation’s 193 million acres of National Forests. A part of the Trump Administration’s push to rollback regulation, the rule would gut one of the essential bedrock laws that protects the right of the general public to know about and participate in decisions that affect federal public land, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

Unfortunately the proposed changes on National Forest lands would create loopholes to increase the speed and scale of resource extraction including logging and mining — while eliminating public awareness and input on up to 93% of proposed projects. The Forest Service has proposed to fast-track environmental review under new “categorical exclusions” allowing the agency to move project planning behind closed doors by cutting out the public from the decision-making process and eliminating any science-based review of impacts to wildlife, recreation, and drinking water, the most valuable resource on our public lands. The rule also runs counter to the agency’s push to manage forests to conserve watershed health and clean drinking water.

National Forests provide drinking water to over 66 million people in 3,400 communities across 33 states. The U.S. Forest Service values the water that flows off of our National Forests alone at over $7.2 billion annually. Healthy forests perform many of the functions of traditional water treatment facilities and water infrastructure. They store water, filter pollutants, and transport clean water to downstream communities, all while operating naturally and essentially for free. In addition to providing these water delivery and filtration services, riparian forests are also considered to be among the most ecologically important. Municipalities, and ratepayers, are increasingly recognizing the value of sound forest management upstream that saves them money.

The proposal would also remove one of the basic safeguards that prevents the agency from fast-tracking potentially harmful projects affecting high value lands and rivers including municipal drinking watersheds, Wild and Scenic Rivers, roadless areas, and potential wilderness areas.

Further, this proposal would facilitate an increase in unnecessary and expensive road-building on National Forest lands contrary to the trend, supported by the agency for years, to remove roads in the vast network of legacy roads as a way to improve watershed health and reduce growing maintenance costs. The sheer number of existing forest roads and stream crossings, many of them poorly designed, represent the largest source of sediment to water bodies from forestry operations.

This rule seeks to turn back the clock on sensible management of our public lands that currently accounts for the myriad of benefits that flow from them, especially clean drinking water. The Trump Administration seeks to remove your voice from decision-making and rollback protections for rivers. Take action now to keep them from doing so.

As the Bloede Dam Removal Project in Patapsco Valley State Park in Maryland is now complete, American Rivers and our partners are reflecting on the history of the project and the site. You can check out photos of the finished project in this recent blog. Now, we want to invite members of the public to share their visions for how to commemorate the unique design of the Bloede Dam, the human and natural history of the surrounding area, and the life of the dam’s inventor, Victor G. Bloede.

Do you love history? Then we have a competition for you!

Bloede Dam | Photo by Jarob J Ortiz

Over the course of the next month, we invite you to learn about the history of the Bloede Dam and why it was such a unique structure with unique operational challenges. Of course, we will be doing typical things for historical interpretation like signs at overlooks and 3D models. However, we want to see what ideas others have for helping the history of this site live on!

Are you up to the challenge? Do you want to win acclaim within the local community? If so, share your ideas with us in this Official Entry Form.

If you really just want to read about the history, you can go straight to the historical documentation here.

All entries into this competition are due by Friday, October 4, 2019. For more information, please see the official entry form at the link above.

Disclaimer: American Rivers reserves the right to utilize any (or none) of the ideas submitted into this competition in the historical interpretation of Bloede Dam.

Bloede Dam was on the Patapsco River in Patapsco Valley State Park in Maryland. The dam was the most downstream structure, and therefore, the lynchpin to reconnecting upstream habitat. American Rivers removed two dams upstream in 2010—Simkins Dam and Union Dam. Finally, more than 65 miles of spawning habitat for blueback herring, alewife, American shad, hickory shad and more than 183 miles for American eel have been reconnected in the Patapsco.

Bloede Dam had served no functional purpose for decades and posed a serious public safety hazard in Patapsco Valley State Park. There were a number of injuries and deaths, with at least nine dam-related deaths since the 1980s, the most recent of which occurred in June 2015.

Patapsco River | Photo by Jessie Thomas-Blate

Today, the construction site is all put back together. The Grist Mill Trail running through the project site has been repaved and is ready for action!

Patapsco River | Photo by Jessie Thomas-Blate

Parts of the slopes are growing new trees and other vegetation, so we ask that people stay on the trails while the site works to restore itself.

Patapsco River | Photo by Jessie Thomas-Blate

We’ve planted thousands of trees on the site to help stabilize slopes and eventually provide shade to the trail. In a few years, this place will not be recognizable.

Patapsco River | Photo by Jessie Thomas-Blate

This is the project manager, Serena McClain. This project could not have happened without her. We are very proud of the work that she has accomplished on the Patapsco River.

Photo by Jessie Thomas-Blate

Of course, here at American Rivers, no person is an island. We work as a team. Here is part of the American Rivers Bloede project team with a tree that we planted in the park in Serena’s honor.

Patapsco River | Photo by Jessie Thomas-Blate

The river’s ready for you to come visit! Have a seat on a bench in an overlook, bring a fishing rod and toss in a line, float around in a tube, have a picnic on a gorgeous exposed rock, or take a hike or bike down the new trail. The Patapsco is a beautiful place to visit (and now safer too!). You can watch a river do its own work to restore itself over the coming years as we will be doing. Nature can do amazing things.

Here in the Pacific Northwest, most people would agree that when it comes to our future, we want healthy rivers, salmon and orcas. We want clean energy. And we want economic opportunity.

But for too long, the conversation surrounding salmon and other native fish recovery and the possible removal of dams on the lower Snake River has been stuck in tired frames: environment vs. economy. salmon vs. agriculture. Seattle vs. Eastern Washington. Meanwhile, salmon and southern resident orcas are slipping toward extinction; the region’s affordable power is at risk; and communities from the Pacific coast to Idaho are missing out on economic potential. Plus, a changing climate is adding new threats and uncertainty to much of what society has taken for granted.

Lower Snake River | Photo by Alison M. Jones

In order to have a constructive conversation, we need to acknowledge the benefits the lower Snake River dams have provided, and we need to understand our options should they be removed. We need to understand not only the costs of removing the dams but also the benefits to the region. We need to understand the true impact – both negative and positive – on existing commerce. We also need to explore what the benefits of a healthy, free-flowing river and revitalized salmon and steelhead runs would look like for the entire Pacific Northwest.

An analysis released by ECONorthwest tackles some of these questions. The main takeaway: there would be substantial public benefits from restoring the lower Snake River.

We live in the Pacific Northwest, a region where we embrace bold ideas, are inspired by natural wonders and dream big about the future. Let’s not shy away from asking “what if?…”

This new study contributes to the dialogue, presenting information and asking key questions. Here are some more questions we’d like to explore, together with others across the region, as a way to move this important discussion forward.

What if we stopped focusing so much on our differences and came together to identify shared values and priorities?

What if we set our sights on a vision for the future that includes healthy salmon, clean energy, thriving agriculture, a strong economy — and ensured everyone moves forward together?

What if we could make investments to revitalize a lower Snake River that sustains people, fish and wildlife?

Lower Snake River | Photo by AlisonMeyerPhotography.com

More than 75 years ago, when the Bonneville Power Administration started building dams on the Columbia River, they hired Woody Guthrie to write songs about the river and the promise of federal hydropower dams. The Lower Snake River dams were built in this spirit of hard work and progress.

Can we harness that same optimism and can-do spirit of “Roll On, Columbia”, when considering restoring a free-flowing lower Snake River? Why couldn’t a revitalized river be a source of great hope, pride and opportunity for our entire region?

Today, we have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to change the course of history and greatly reduce the extinction risk for endangered salmon and steelhead. To do this, we need healthy dialogue and open minds to foster the emergence of new economies. The people of the region deserve to have the information and they deserve to have their voices heard. Let’s get the information and let’s move forward together. Let’s all keep asking “what if?”

On a sunny summer morning in the mountains of North Carolina, I stepped into an inflatable kayak and set off down the Tuckasegee River. Known affectionately as the Tuck, this river was named after daksiyi, the Cherokee word for “box turtle place.” It flows from the mountains of northeast Georgia across North Carolina and into Tennessee, forming a part of the Little Tennessee River watershed.

My colleague and I were paddling the newly established Tuckasegee Blue Trail — a pristine 60-mile stretch of stream celebrated for fishing, boating and exploring. Just as hiking trails are designed to help people explore the land, blue trails like this one help people discover rivers.

Tuckasegee River | Photo by Jack Henderson

Today, we paddled my favorite section of the Tuck. My heart pounded as we navigated Dillsboro Drop — a beautiful, natural rock ledge and the first in a series of class II and III rapids. I knew the area was rich in native mussels and fish, who moved back after a dam was removed from this exact spot in 2012. We continued over rocky riffles teaming with trout and by riverbanks shaded with native river cane and rhododendron as we eased our way downstream. While we took a break on one of the sandy riverside beaches, families floated by in rafts and canoes, and bald eagles soared overhead. I breathed in the mountain air and considered how special this place is — and why I work every day to protect it.

The Tuck has long been a focus of American Rivers’ conservation efforts in the Southeast. After years mapping out a vision and working alongside local leaders to identify goals for conserving the river and its adjacent lands, we’re thrilled to finally celebrate the official designation of the Tuckasegee Blue Trail in 2019. The newly available blue trail map pinpoints the best spots for fishing, wildlife spotting, cultural exploring, picnicking and camping.

Connecting local people with their hometown river is just part of American Rivers’ broader efforts to protect this aquatic home for myriad fish, mussels and river life found nowhere else in the world.

“The sicklefin redhorse is a fish native just to western North Carolina,” says Mike LaVoie, the Natural Resources Manager for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. “This fish used to migrate in large numbers and really provided a dependable source of protein after a long winter. Even though it wasn’t described by science until the early 90s, Cherokee always had a name for it, which translated to ‘wearing a red feather.’ Traditional ecological knowledge superseded scientific knowledge for this species’ significance.” The Cherokee people have deep roots in the Tuck, controlling just a tiny fraction of their original aboriginal land, and play an active role in river restoration in the Little Tennessee watershed.

“It’s about us helping to put that puzzle back together,” LaVoie says.

Another critical piece of the restoration puzzle is lessening the impacts of climate change, urbanization and erosion on water quality and the river ecosystem.

Tuckasegee River

“If you put a frog into a bucket of hot water, it will jump out,” says Jason Meador of Mainspring Conservation Trust, an organization dedicated to conserving and restoring lands and waters of the Southern Blue Ridge. “If you gradually let the water warm up, the frog will never realize it’s a problem. Sedimentation is the same way: It happens over decades, and no one notices the problem until it’s too late.”

American Rivers is taking a landscape-wide approach to conserving the Little Tennessee watershed along with partners like Mainspring Conservation Trust and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians as part of the Little Tennessee Native Fish Conservation Partnership. This Partnership supports the first Native Fish Conservation Area designated in the country and joins 25 state and federal agencies and nongovernmental organizations in conservation. The Partnership works with local communities to protect native species such as the endangered Appalachian elktoe mussel and the sicklefin redhorse fish in this amazingly diverse ecosystem.

Together with our partners, we are executing projects, such as river restoration, and leveraging funding on a scale none of us could make possible on our own. We are engaging local farmers and communities and raising their awareness of the uniqueness of their river system.

“How well people take care of the land determines how healthy our river and waters are,” Meador says. “Once we engage with folks and they understand the watershed concept, they realize why our little creek is so important and why we must do everything we can to make it healthier.”

High Falls, Tuckasegee River | Photo by Kasia Halka

LaVoie adds: “Our vision is to have a river system that more resembles how it was before Europeans were in the area, and to have our native fish and mussels abundant and available for Cherokee to utilize for subsistence purposes. We are constantly thinking about clean water and what it means for human use and native fauna. We want more of our community in the river fishing, swimming and connecting to it, so that they value it and can sustain it into the future.”

Back on the Tuckasegee Blue Trail on that vibrant summer day, I wondered: What if we can take out the Cullowhee Dam and help the Tuck flow freely once again? What if we can write a new future for the Appalachian elktoe mussel and sicklefin redhorse? What if we can find new ways to give people greater access to their river? What if we can keep the rivers in the Little Tennessee swimmable, fishable and drinkable for future generations?

All this — and more — is possible, with our strong partnerships, dedicated supporters and a clear vision of what the future could be.

Harpeth River, Nashville, TN

The Harpeth River has a great variety of fish and is a hotspot for fishing, paddling and hiking. It has many public access points throughout the 125 miles of river making it easy for families to swim, fish, and paddle. While canoeing and fishing, you’ll come across great blue herons, river otters, smallmouth bass, darters, salamanders, and more. Folks also stop to camp or swing on a rope swing. This is a family friendly and small river that is near and dear to the hearts of many middle Tennesseans.

Maumee River, Grand Rapids to Toledo, OH

It is great to kayak the stretch between Grand Rapid and Maumee/Toledo. Depending on the time of year, it can be shallow enough to almost walk across or high enough that you don’t have to portage. It is a great way to get away from the city and feel like you are in a different world.

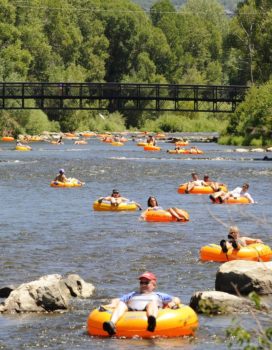

Tubing on the Harpeth River | Photo by Judy Heumann

French Broad Paddle Trail, Asheville, NC

The French Broad Paddle Trail is a series of access points and campsites along the French Broad River connecting over 140 miles of river. The paddle trail begins in Rosman, NC, taking paddlers over flat and whitewater. It passes through an incredibly beautiful geographical region of the Southeast. Many different sections exist to paddle. Find out more here.

South Fork of the American River, Coloma to Greenwood, CA

The Class II section of the South Fork of the American River (C to G) is a gentle float trip, but tenacious kayakers find plenty of play spots along the way as well. Most of C to G is calm with very few rapids of note. Take-out is available at the Greenwood Creek River Access and is managed by the Bureau of Land Management, making it free to park for the day.

Trouble Maker Rapid on the South Fork American River | Photo by Julie Fair

Whitetop Laurel Creek, Damascus, VA

You can find Whitetop Laurel Creek along the Virginia Creeper Trail in Southwestern Virginia. The Virginia Creeper Trail is a great place to combine river play, fishing, and biking, in a way that you can alternate between activities and keep it fun for kids all day.

Desolation/Gray Canyons of the Green River, Sand Wash to Swasey’s, UT

This 84 mile stretch cuts through the remote ramparts of Tavaputs Plateau in central Utah. A Class II-III premier multi-day trip on the Green River is typically done in 5-9 days, and is great for families who have whitewater experience. Permits are required, and an annual lottery is held each winter.

Rogue River, OR

Family-friendly 4-day trip on a class III stretch punctuated by 2 class II rapids. Lots of fun ducky opportunities, rocks to jump off, and side creeks to explore. If you go in the fall the salmon fishing is great.

Communities along the Waccamaw and conservation partners, have made the Waccamaw River a recreational and economic attraction, moving it out of the shadow of nearby Myrtle Beach and into the spotlight across the region. By protecting riverside tracts of land and creating an ideal setting for people to enjoy the river’s natural beauty, recreation and tourism to riverside communities and the Waccamaw River has flourished.

Waccamaw River | Photo by Gator Bait Adventure Tours

American Rivers and our partners are celebrating the Waccamaw River and its immeasurable benefits for people and nature by launching Welcome to the Waccamaw!. This story map provides an interactive and engaging way to understand the significance of this blackwater gem, its threats, and steps we can take to protect this national treasure.

Considered one of the finest blackwater rivers in the Southeast, the Waccamaw River provides communities in North and South Carolina with clean drinking water, scenic landscapes, diverse fish and wildlife, and outstanding recreation opportunities which substantially benefit the regional economy. The river’s crown jewel is the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge, which protects the diverse habitat of the river corridor and the greater Winyah Bay watershed for wildlife like the swallowed-tailed kite, coastal black bear and a wide variety of rare plants. Additionally, the area provides amazing outdoor recreation opportunities for boating, fishing, birdwatching and more.

Recurring floods resulting from a spate of recent hurricanes and extreme rainfall events have flooded homes, businesses, roads and communities along the Waccamaw River. Rather than a threat, a healthy Waccamaw with protected floodplain lands are part of the solution, valuable assets for increasing flood and climate resiliency. The river’s vast forested floodplains store floodwaters to protect downstream communities, provide critical habitat for rare plant and wildlife species, and filter pollutants essential for the region’s clean drinking water.

Waccamaw Flooding | Photo by Robbie BischoffWelcome to the Waccamaw! helps people understand the many community and environmental benefits of the Waccamaw River and Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge. It describes the impacts of flooding and climate change, along with rapid population growth and poorly planned development that threaten the area. The story map also shows how protecting and restoring floodplains, and other riverside lands are part of the solution to improve the resiliency for communities along the Waccamaw by reducing flood risk.

Explore Welcome to the Waccamaw! to learn about how the health and security of surrounding communities are closely tied to the river, the refuge and their abundant forested floodplains.

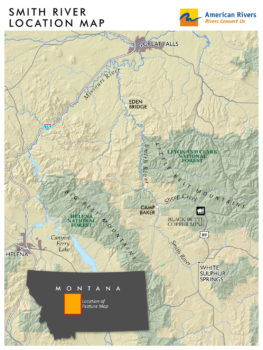

Now that the public comment period has closed on a draft study of the environmental impacts of a proposed copper mine in the headwaters of Montana’s Smith River, a lot of folks have asked us – what’s next?

Before answering that question, let’s recap what the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) heard from the public during the 60-day comment period that ended on May 10. A total of 12,600 people submitted comments to the Montana DEQ, at least 90 percent of whom opposed construction of the controversial mine. The state initially reported receiving only 2,500 comments, however recently it was discovered that another 10,000 comments submitted through third-party websites got stuck in its spam filter.

So on that front, we crushed it. Thanks to each and every one of you who sent in comments.

Smith River Area Map

That said, the public comment period wasn’t a popularity contest, as mine proponents and state regulators like to remind us. If it was, the mine proponent, Sandfire Resources America, would have folded up its tent and headed home to Perth, Australia, and the Smith River would stay just the way it is – not perfect, but damn near.

The biggest news to come out of the public comment period was that the proposed Black Butte copper mine was exposed for what it is – a risky experiment built on false assurances.

How do we know this? Because American Rivers and our conservation partners hired a team of top-notch mining and natural resource experts who examined the draft environmental impact statement with a magnifying glass. Here are a few things they discovered:

- Despite Sandfire’s claim that the mine tailings would be rendered non-flowable by mixing them with a cement paste and therefore not pose a threat to surface or groundwater, the cement would start dissolving in acid in a matter of weeks.

- The DEQ’s conclusion that the mine wouldn’t pose a threat to water quality or fisheries in Sheep Creek and the Smith River was based in part on the flawed assumption that the double liner underneath the mine tailings would never tear and never leak. The fact is, ALL liners eventually leak.

- The DEQ’s conclusion that the mine wouldn’t dewater Sheep Creek (the Smith River’s most important rainbow trout spawning tributary) was based on a flawed model that underestimated how much water would have to be pumped from the mine.

- The DEQ didn’t address the fact that Sandfire holds 525 mining claims on 10,000 acres of adjacent federal lands. Consequently, it didn’t assess the cumulative impacts that dramatically expanded mining operations would have.

Smith River | Photo by Pat Clayton

Despite these serious flaws, the Montana DEQ still plans to release its final environmental impact statement on the Black Butte copper project early this fall. Once that happens, the DEQ can then issue a Record of Decision (ROD) that approves the application as submitted, approves the application with modifications, or denies the application if it doesn’t comply with Montana’s laws, specifically those pertaining to water quality.

While we are hoping that the thousands of comments Smith River advocates submitted and the technical comments our team of consultants submitted convince the DEQ to deny Sandfire the permit it needs to build the mine, we are prepared to carry on this fight if the state abrogates its responsibility to uphold Montana’s environmental laws.

When we say the Smith River is too precious to risk, we mean it.

Whatever the outcome, you can rest assured that Sandfire will not start building its proposed copper mine in 2019, as it is telling its investors. This fight was always going to be a marathon, not a sprint.

This blog post was written by Kelly Romero-Heaney, Water Resources Manager for the City of Steamboat Springs. Join us to learn more about Steamboat’s connection with the Yampa River.

The Yampa River is wild…mostly.

Its 7,660 square mile watershed contributes to over 250-miles of river flowing through Steamboat Springs and down to ranching towns, like Hayden, Craig, and Maybell before carving its way through the spectacular Yampa Canyon in Dinosaur National Monument where it meets the Green River in Echo Park.

Yampa River | Photo by City of Steamboat Springs

Unlike the majority of Colorado rivers, there are no trans-basin diversion conveying its waters to the East Slope to serve the sprawling Denver Metro Area and there is no major reservoir on the Yampa River that would interrupt its natural flow of water and sediment. But the Yampa River is still a managed system and wild only to a degree. Several small reservoirs – the largest of which is Stagecoach Reservoir at 36,000 acre-feet – can influence flows in the late summer. There are hundreds of agricultural diversions that support flood-irrigation of hayfields and municipal and industrial diversions that supply the Yampa Valley communities plus two coal-fired power plants. There is even an artificially constructed Recreational In-Channel Diversion – a recreational water right that doesn’t take water out of the Yampa but that conveys flow in a way to enhance the recreational experience for rafters, kayakers, SUP-ers, and tubers in Steamboat Springs. In addition to a century of riparian vegetation removal to make way for hayfields and urban development, decades of gravel-mining has reconfigured the channel above Steamboat and disconnected the river from its floodplain in spots.

Only a bunch of scrupulous water managers would conceive of footnoting a phrase that fits so nicely on a bumper sticker –The Yampa is Wild. But truth be told, the Yampa is about as wild as it gets in Colorado.

Yampa River | Photo by City of Steamboat Springs

Living on a wild river means that the people that use the river – the ranchers, the recreationalists, and the water drinkers – have adapted to flow variability on this scarcely regulated river. For example, 2018 was a particularly hot and dry year with stream temperatures nearing 80-degrees Fahrenheit in Steamboat Springs. To reduce stress on aquatic life, the City responded with voluntary river closures to all river recreation. Tube rental companies and fly-fishing outfitters took an economic hit and visitors to the area didn’t get to play in the Yampa River as planned. In contrast, this summer the Yampa River is flowing fast and wild late into this summer thanks to a last season’s great snowpack coupled with a lingering wet and snowy spring. The Yampa is so fast, in fact, that tube rental companies are shut down due to dangerously high water conditions. But the rafting is fun, the hayfields are green, and the trout and native whitefish are receiving a reprieve from multi-year droughts and the warm water they’ve endured.

Being a wild river also means that the Yampa is measurably healthier than most rivers thanks to the incremental flow of water, sediment, organic matter, seeds, and debris that its natural flood waters deliver to its floodplain. This recipe for a healthy river system provides a corridor for wildlife and river runners alike.

Geovanny on the Yampa | Photo by Kelly Romero-Heaney

Geovanny (my husband) and I spent a therapeutic hour paddle-boarding sans kids last Sunday evening. It was a shorter float than expected due to the still swift current, but just an hour float from the river’s Walton Creek confluence to its Fish Creek confluence told the tale of this managed yet still wild river. Our float began in a backwater slough formed by historic gravel mines and surrounded by dense willows and alders. We quickly met the main channel where a steady pattern of pool, glide, riffle, run required a degree of concentration to stop this less than experienced SUP-er from falling into the bumpier waters. We paddled by the ski area’s snow-making intake, beneath a cottonwood forest with osprey nests above, by a fly fisher casting from her paddleboard, by a tourist family skipping rocks from a high bank, and through an irrigated hayfield on a city-owned conserved parcel.

A railroad bridge spanned the final bend before our takeout and as I drifted towards the center of the trusses, I spotted a dark furry movement to river left. A black bear appeared from the willows and fearlessly trotted across the bridge just as I approached it. There was nothing I could do to stop from drifting just beneath him as he went along his merry way. I surrendered to the current, hoping that he didn’t leap, smiling with gratitude that I live on this this vastly wild river.

Join us and listen in to Episode 4 of Ripple Effects as we explore the incredible connection the City of Steamboat Springs has with its local river, the Yampa.

Twenty years ago, the annual run of alewives (a migratory fish essential to the marine food web) up Maine’s Kennebec River was zero. Today, it’s five million — thanks to the removal of Edwards Dam and additional restoration measures upstream. The Kennebec and its web of life have rebounded in many ways since Edwards Dam came down in 1999.

A rush of water surged through Edwards Dam as the Kennebec was freed on July 1, 1999

The removal of Edwards Dam was significant because it was the first time the federal government ordered a dam removed because its costs outweighed its benefits. The restoration of the Kennebec sparked a movement for free-flowing rivers in the U.S. and around the world.

According to the dam removal database maintained by American Rivers, 1,605 dams have been removed in the U.S. since 1912. Most of these (1,199) have occurred since the removal of Edwards Dam in 1999. The year with the most dam removals was 2018 (99 dams removed). 2017 was the second most productive year, with 91 dams removed.

The lesson from the Kennebec after twenty years? Dam removal works. Our partners at the Natural Resources Council of Maine report that since Edwards Dam was removed on July 1, 1999, tens of millions of alewives, blueback herring, striped bass, shad, and other sea-run fish have traveled up the Kennebec River, past the former Edwards Dam, which blocked upstream passage since 1837. Abundant osprey, bald eagles, sturgeon and other wildlife have also returned.

“The precedent setting 1999 Edwards Dam removal continues to surprise us all with the dramatic recovery of the river and its native fish,” said Steve Brooke, who worked for American Rivers in Maine and led the Kennebec Coalition. “Each year the numbers of returning fish grow and document the fact that our rivers can restore themselves given a chance.”

Kennebec River | Photo by Liam McAuliff

On a basic level, dam removals matter for the specific rivers and ecosystems that are restored to health. But looking at the bigger picture, dam removals also matter in terms of our relationship with all rivers – because with every individual act of restoration we’re creating a new and compelling picture of what the future can look like. We’re spotlighting the benefits that healthy, free-flowing rivers can naturally provide. We’re demonstrating the power of local citizens to drive positive change. And we’re proving that communities can reclaim their rivers and their stories.

Here’s a look at some recent river restoration successes – and rivers to watch for the next big opportunities:

Northeast

The Penobscot River

Success: Penobscot River (Maine)

On the Penobscot River, removing two dams (Great Works in 2012 and Veazie in 2013) and installing fish passage at others opened nearly 1,000 miles of habitat to migratory fish. Thanks to modifications at other dams in the watershed, hydropower production on the river has remained the same. Learn more

What’s next:

In dam-dense New England, partners are working across hundreds of rivers and dams to reconnect habitat. We are excited about the upcoming removals and potential for new dam removal projects that would hold big wins for migratory fish, including dams on the Ipswich River in Massachusetts, Sheepscot and Presumpscot Rivers in Maine.

Southeast

Neuse River | Photo by James Willamor

Success: Neuse River (North Carolina)

Removing Milburnie Dam on Raleigh’s Neuse River in 2017 improved public safety (15 people drowned in the hydraulic created at the abandoned powerhouse) and restored habitat for migratory fish including shad and striped bass. Learn more

What’s next:

This summer American Rivers staff and partners in North Carolina are kicking off a project to remove the Ward’s Mill Dam, which is the #1 ranked dam in the North Carolina barrier prioritization tool. This project will improve public safety, habitat for eastern hellbenders and freshwater mussels and recreation.

American Rivers is also working in the Cullowhee community in North Carolina to remove a deteriorating dam that currently provides the pool where Western Carolina University and the county draw their drinking water. We are working closely with our partners to envision a “run of river” intake that does not rely on a dam to provide drinking water. This project will support a resilient water supply, expanded habitat for endangered species, and create recreation opportunities in a river park.

Mid-Atlantic

The Patapsco River | Photo by Jim Thompson

Success: Patapsco River (Maryland)

In addition to eliminating a public safety risk, the removal of Bloede Dam will give a tremendous boost to the health of the river ecosystem, including fisheries critical to the food web of the Chesapeake Bay. The removal of Bloede Dam is the linchpin of a decades-long restoration effort that also included the removal of Simkins Dam (2010) and Union Dam (2011). Removal of Bloede restores more than 65 miles of spawning habitat for blueback herring, alewife, American shad, and hickory shad in the watershed, and more than 183 miles for American eel.

What’s next: Potomac River (MD)

The Potomac River Industrial Dam is located on the North Branch of the Potomac River in downtown Cumberland, Maryland. This outdated infrastructure not only blocks 43 miles of habitat for American eel and other aquatic species, it is a barrier to the city’s broader vision for a thriving river-centered recreation economy. With ownership of the structure in question, the project has remained in limbo. Now is the time to refocus on efforts to address this unsafe dam.

Northwest

Elwha River | Photo by Lance McCoy

Success: Elwha River (WA)

Removal of Elwha and Glines Canyon dams began in 2011 and was completed in 2014, and since then the entire watershed — from the headwaters in Olympic National Park to the sea – has rebounded back to life. Learn more

What’s next:

Middle Fork Nooksack (Washington)

Removal of the Middle Fork Nooksack Dam near Bellingham will begin in the summer of 2020. The effort will reestablish access to approximately 16 miles of critical spawning and rearing habitat for Puget Sound Endangered Species Act listed chinook salmon, steelhead, and bull trout. The project will also maintain the City of Bellingham’s municipal water supply.

Lower Snake River (Washington)

Removing four dams on the lower Snake River in eastern Washington provides a once in a generation opportunity to recover endangered wild salmon and steelhead runs in the Columbia-Snake watershed (including Idaho’s Salmon and Clearwater rivers, northeast Oregon’s Imnaha and Grande Ronde, and southeast Washington’s Tuccannon), while creating new economic opportunities and investing in a clean energy future.

Midwest

The Baraboo River

Success: Baraboo River (Wisconsin)

Five dams were removed from the Baraboo River, beginning in the 1990’s. Since then recreation has increased and surrounding communities plan to add new opportunities for water recreation and riverside trails. They hope to earn National Water Trail Status with the longest free-flowing (120-miles) and fully-accessible river trail.

What’s next:

Mississippi River (Minnesota)

American Rivers and our partners are calling for removal of two U.S. Army Corps of Engineers locks and dams on the Mississippi River in Minneapolis. Restoring a free-flowing river in the Mississippi Gorge would create new recreation and economic opportunities, improve fish and wildlife habitat and allow the Twin Cities to reconnect with a revitalized river.

Kinnickinnic River (Wisconsin)

Removing two aging dams on the Kinnickinnic River in River Falls would revitalize and restore the Lower Kinni’s cold water habitat, resurrect an entire mile of this world class stream, and fully restore the historic Junction Falls waterfall in the heart of the city. Learn more

California

Klamath River | Photo by Daniel Nylen

Success: Holy Jim Creek, San Juan Creek, and Trabuco Creek

The Cleveland National Forest removed 33 dams in total—18 dams from Holy Jim Creek, four in upper San Juan Creek, 10 in lower San Juan Creek and one from Trabuco Creek—in 2018. The dams were originally constructed for varying uses; however, years of disuse and, in some instances, a 40-year maintenance backlog resulted in the decision to remove these structures as a way to restore these streams and provide access to habitat for fish and wildlife. The efforts of the Cleveland National Forest demonstrate the power of coupling smart management of outdated water infrastructure with the potential re-establishment of extirpated species like the southern California steelhead trout.

Klamath River (Oregon, California)

Removing four dams on the Klamath River – slated to begin in 2021 — will restore more than 300 miles of salmon habitat for salmon, and improve water quality. Learn more

Want to keep up to date about river restoration successes? Sign up and we’ll share news and alerts.

What is a toxic algae outbreak and where do they occur?

If your river or lake is choked with green slime, it might be a toxic algae outbreak. These outbreaks are triggered by several factors, including warm temperatures and excess nutrients from agricultural and urban runoff. Last year there were toxic algae outbreaks in Oregon, Florida and other states across the country. Because the algae thrives in warm temperatures, summer is the time to be aware of outbreaks in our communities.

How can they harm people and pets?

Toxic algae outbreaks are a serious threat to our health, economy, drinking water supplies and fisheries. The algae releases harmful toxins in the water as it grows. It can be toxic if consumed, causes skin and respiratory irritation, and can be fatal to dogs that swim in or drink the water. Salem, the capital of Oregon, was under an advisory for weeks in the summer of 2018 because of a toxic algae outbreak in its water supply. Children under six years old, pregnant women, nursing mothers and adults with compromised immune systems were told not to drink the water. An outbreak in Lake Erie in 2014 left 500,000 people in Toledo, Ohio without drinking water for three days.

Sassafras River, VA | Photo by Eric Vance

What causes outbreaks?

Land-use practices and climate change are making toxic algae outbreaks worse. That’s because the algae is fueled by phosphorous and nitrogen in fertilizer running off farmlands, and runoff from urban and suburban areas. Plus, the algae thrives in warmer waters – and temperatures are rising with climate change.

What can we do to stop these outbreaks and protect clean water?

On a national level, one crucial first step is stopping the Trump administration’s rollback of the Clean Water Rule. Among many other benefits, this rule protects the streams and wetlands that are natural sinks for excess nutrients. They keep chemicals out of our water supplies, which prevents algal blooms.

On the local level, we need to keep advancing green infrastructure solutions that reduce the flow of pollution into local streams. What does this look like? – green roofs, more trees, rain gardens, more natural areas. All of these solutions naturally absorb and filter pollution, minimizing the toxins that flow into our streams, rivers and lakes.

Learn more

Visit Environmental Working Group and the Center for Disease Control to learn more about the health impacts of toxic algae.

This blog is part of our series on America’s Most Endangered Rivers®– Buffalo National River. Learn more about how you can help rivers like the Buffalo in our Action Center.

Today is a good day for the Buffalo National River.

Thanks to the hard work of local advocates and thousands of our supporters from across the country, Arkansas’ Governor Hutchinson has made a deal to close the industrial hog farm that has been impacting water quality and causing algae outbreaks stretching 70 miles downstream in the Buffalo National River. Further, the Governor plans to institute a ban on new medium and large-scale hog farms in the watershed. This is a huge win, and it couldn’t have happened without our supporters taking action.

Thank you for stepping up!

In 2017, and again in 2019, American Rivers partnered with local groups to fight this hog farm through our annual report on America’s Most Endangered Rivers®. We shined a national media spotlight on this issue and elevated it in the public eye beyond the local community. We also shared a series of eight blogs highlighting why the Buffalo National River is such a special place and urging people to take action on behalf of the river. Between 2017 and 2019, our activists across the country sent thousands of letters to the Governor asking that the permit for the farm be denied.

You told the Governor that polluting the Buffalo National River with hog waste was unacceptable, and the Governor heard the message loud and clear!

Buffalo National River | Teresa Turk

We are so grateful for the local advocates that put their hearts and souls into fighting this hog farm on the Buffalo, including Ozark River Stewards, Ozark Society, Buffalo River Watershed Alliance and others. Without the boots on the ground, it is nearly impossible to fight projects such as this. They did a fantastic job drawing the attention of people across the country to harm being brought to America’s first National River, the Buffalo.

Our local partner, Teresa Turk, expressed her appreciation for our partnership by saying, “Wanted to let you know the incredible news today! The governor is closing the hog factory. All the great efforts and support from American rivers helped to make this happen!!!” Another local partner, Lin Wellford, said, “I definitely think Endangered Rivers played a huge part in taking our plight to a national level. Kudos to you and all your staff for helping us finally hit a tipping point that no one thought we would ever hit. Please spread the news far and wide to give all those other river advocates hope that they too may slay the dragons they face.”

Buffalo National River | Teresa Turk

With these types of campaigns, it can be helpful to have both local and national energy combined to get people’s attention. This is a great example of how American Rivers works with local groups to protect rivers from harmful threats and pollution. We are very proud and supportive of these local advocates who do whatever it takes to make the situation right for the river.

We hope you will join us in celebrating this victory! This as an example of what can happen when we all work together to get the job done.