Episode 22: Climate Change Part 2 –Climate Change is Water Change

Join us for Episode 22 of We Are Rivers, Climate Change Part 2: Climate Change is Water Change, where we build upon our knowledge of climate change science to explore changes affecting the already parched American Southwest.

2019 was a wild weather year around the globe with temperatures breaking records and extreme weather events like hurricanes, massive flooding and wildfires impacting communities, people, and ecosystems. No corner of the globe was spared from its impacts, including the Southwest and Colorado River Basin. Join us for Episode 22 of We Are Rivers, which builds on our understanding of the science behind climate change.

The Upper Colorado River Basin had record precipitation during the 2018 – 2019 winter, it was the second highest amount of precipitation recorded since 1900. At the annual Colorado River District Water Seminar, Jeff Lukas with the Western Water Assessment noted that not only did we experience a tremendous amount of precipitation but this winter was the coldest winter since 2010. The cold, wet winter built a significant snowpack in the mountains (130% of average snowpack in the Upper Colorado River Basin). Snowpack is essential for the region as the Colorado River and most other rivers in the region are primarily driven by runoff that melts throughout the spring and summer. Runoff provides rivers with flushing, peak flows and a firm baseline heading into fall. A wet, cold winter was welcome after one of the worst drought years in 2018, and this year’s snowpack pushed the state of Colorado out of a statewide drought conditions for the first time in 20 years.

However, winter wasn’t the only season in the record books this year. The Southwest experienced extreme heat and lack of precipitation in the later months of the summer. In his Colorado River District seminar presentation, Jeff Lukas noted that June – August 2019 was the 8th driest year since 1900, with July and August being the 6th warmest. Despite the significant snowpack, the hot summer temps coupled with dry soils and reduced late summer flows resulted in a smaller runoff that might have been anticipated. This year’s runoff was 118% of average at Lee’s Ferry versus the 130% of average snowpack for the Upper Colorado River Basin.

Warmer winter temperatures hold more moisture in the air – in turn, the warmer summer temperatures increase evaporation and dry the region out much faster than in the past. This not only reduces soil moisture but also river flows. Between 2000 and 2014, the Colorado River experienced a 20% reduction in flows when compared to the period of 1906-1999. According to Brad Udall and Jonathan Overpeck, one-third of this reduction is linked to warming temperatures and it’s likely that flows will only continue to decline as temperatures continue to rise.

“Weather whiplash,” a term coined by climatologist Dan Swain, can best describe our new normal in the Colorado River Basin. The whiplash of temperatures, precipitation, and extreme weather attributed to climate change affects all corners of the globe. Regions like the Southwest that are already dry will experience increased vulnerability in the form of higher temperatures, variable precipitation, earlier runoff, more intense wildfires and punctuated flooding events. These events will only intensify over time and will vary depend on the specific location within the region – some areas will get hotter and drier while other will experience more precipitation in the winter months. As Brad Udall says in the podcast, in the Colorado River Basin, climate change is water change.

One thing everyone can do to address the climate crisis is to call your representative and let them know it’s time to take action on climate change! We must reduce greenhouse gases and make our communities and ecosystems more resilient to a changing climate. We need to use more renewable energy sources, improve renewable portfolio standards, ensure regulations are in place to reduce greenhouse gases, and develop new technologies utilizing renewable energies. Let your representatives know that along with slowing global warming (by reducing greenhouse gases), we must adapt to the changes we are already experiencing. This includes protecting and restoring the wetlands, forests, and riverside lands that slow floods and provide clean water is essential to help us adapt to the new normal. Together, we can use water more efficiently and install green infrastructure to decrease polluted runoff, improve air quality, and lower temperatures. Make your voice heard today – do your part.

One hundred-fifty years ago this past August, John Wesley Powell and his crew camped where the Little Colorado River meets its larger cousin in the heart of the Grand Canyon. Thanks to stewardship and forethought, little has changed about the confluence since that time. The Little Colorado River – called Paayu by the Hopi, the Rio Chiquito by Spanish explorers, and the Flax River by pioneers – has carved a dramatic, steep and narrow gorge through the red rock of the Colorado Plateau, reaching over 3000 feet deep by the time it meets the Colorado River. Ravens still whirl overhead, coyotes still call from the mesa, and native fish still spawn in the spring-fed waters of the canyon.

Both Powell expeditions – in 1869 and 1871 – happened upon the Little Colorado River when it was in flood, its waters thick and brownish-red with silt and debris from monsoonal rains. This is typical of the Little Colorado, which experiences two hydrologic peaks: one in early spring from snowmelt in the White Mountains, and one in late summer as monsoons sweep across the desert Southwest, bringing much needed moisture to lands parched by summer heat. These brief floods can be large, moving tons of habitat-creating silt into the Colorado River and giving the river a tempestuous reputation. The highest recorded flow of the Little Colorado was a whopping 120,000 cfs in 1923.

Even back in 1869, the Powell Expedition members were relative newcomers to the area. Humans have inhabited the Little Colorado River since the early Holocene, over 8000 years ago. The Navajo and Hopi nations both maintain culturally important roots and sacred sites in the lower canyon – sites like Blue Spring which provides the Little Colorado with a perennial flow of cerulean blue water, and the Hopi Salt Mines that start where the Little Colorado’s canyon intersects the Colorado River at the start of Upper Granite Gorge in Grand Canyon National Park.

Native fish also evolved in the Little Colorado’s natural, year-round flows. The endangered Humpback Chub maintains its most important breeding ground just upstream of the mouth of the Little Colorado. The silt, debris, natural hydrograph and warmer water provided by the Little Colorado River are important to the larger Grand Canyon ecosystem downstream. And of course, people love to recreate there: The Little Colorado has provided a Caribbean-like refuge of warm, blue waters to Grand Canyon river runners and photographers for decades.

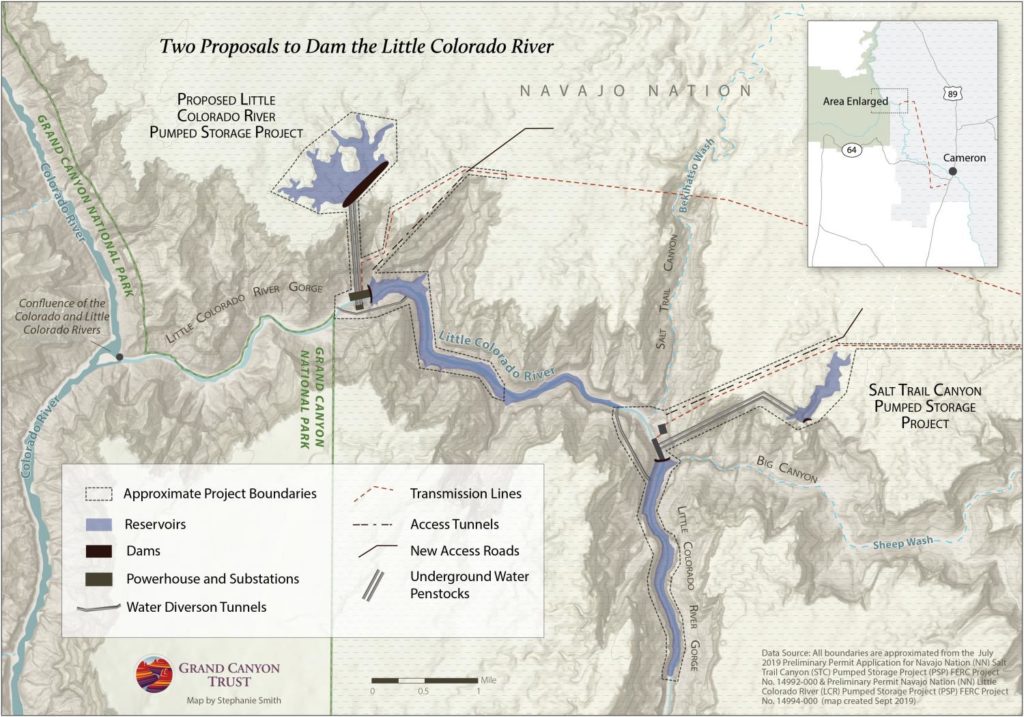

But all of that could change. While the Little Colorado River still retains all of the special qualities that it has had since time immemorial, it is increasingly threatened by development schemes. First, it was the proposed Grand Canyon Escalade, which thankfully the Navajo Nation Council voted against in 2017. Now the immediate threat is a pair of “pumped storage” preliminary permit proposals that could include building two new dams each just up from the confluence: A new 140-foot high by 1000-foot long concrete arch dam on the river and a new 240-foot high by 500-foot long dam on the mesa top, connected by an 8000-foot long by 32-foot diameter penstock, a new 2-mile long access tunnel for vehicles, a massive concrete tailrace, new powerhouse and associated infrastructure such as transmission lines. What is now one of the wildest and most sacred parts of the Grand Canyon would essentially become an industrial park should this unlikely proposal become reality. Sacred sites would be flooded, the ecosystem would be forever altered, and the character of one of the natural wonders of the world – the Grand Canyon – would be forever changed.

The preliminary permits for the proposed “Navajo Nation Salt Trail Canyon Pumped Storage Project” and the “Little Colorado River Pumped Storage Project” were filed by Phoenix-based Pumped Hydro Storage, LLC with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC,) and was published in the Federal Register, on September 23, 2019. This filing started a 60-day comment period under the Federal Power Act.

It is important to understand that a preliminary permit only allows the developer to hold a location for a potential future proposal. It is not a license application. In fact, a preliminary permit is not even required to submit a license application or receive a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) hydropower license. To learn more about hydropower licensing, visit the Hydropower Reform Coalition’s website.

While it is unlikely that this project will ever advance past this phase, proposals like this underscore the importance of permanently protecting our last, best rivers like the Little Colorado.

If this project is ever legitimately proposed, American Rivers will stop it. We will intervene in this preliminary permit process, but you too can help by taking action here.

Our predecessors fought off proposed dams in the Grand Canyon at Bridge Canyon and Marble Canyon nearly 50 years ago, protecting the natural and cultural wonder that we love today. Many people, including multiple tribes, came together to stop a proposed tram in the same area of the canyon.

Help us keep Grand Canyon free of dams and other unwise, and unwelcome, industrial development. The Grand Canyon is one of the most iconic landscapes in the world. We aim to keep it that way.

Blog by Mike Fiebig, Sinjin Eberle, and Matt Rice

Today marks the 51st Anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. While certainly not as splashy as last year’s high profile 50th today provides a great opportunity to take stock of the major steps the river community has taken to achieve the goals of our 5,000 Miles of Wild Campaign to protect and defend our nation’s remaining free-flowing rivers.

Along with our partners NRS, REI, OARS and Yeti, American Whitewater and others we launched this campaign in 2017 to protect 5,000 miles of rivers and 1,000,000 acres of riverside lands by October 2, 2020. Despite a political environment that has been openly hostile to conservation over the past couple of years, we and our partners have made great progress and have protected nearly 1,900 miles of rivers — and over 5,000 more miles are in the hopper.

Communities from Massachusetts and Montana have rallied behind protection of their backyard rivers. The hard work of groups like the Nashua River Watershed Association, Friends of the River, the Farmington River Watershed Association, Molalla River Alliance, and K.S. Wild helped organize river communities in support of these new designations. The rivers that these groups helped protect include East Rosebud Creek in Montana, important tributaries of the Rogue River, the Molalla, and Elk Rivers in Oregon; the Wood-Pawcatuck Rivers in Rhode Island and Connecticut; the Amargosa River, Deep Creek, Surprise Canyon and other desert streams in California; the Green River in Utah; the Farmington River and Salmon Brook in Connecticut; and the Nashua, Squannacook and Nissitissit Rivers in Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

In addition to these legislative protections we have also helped secure new administrative Wild and Scenic River protections for over 1,200 miles of rivers and nearly 400,000 acres of riverside land on public land that will keep them free-flowing and protect their outstanding values. In Oregon and Washington on the Malheur, Wallowa-Whitman, and Umatilla National Forests we helped secure Wild and Scenic eligibility determinations for vital tributaries of the Snake and Grand Ronde Rivers. Similarly in Montana on the Flathead, Custer Gallatin, and Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forests we won key long-term protections for portions of the Gallatin, Madison, Yellowstone, Boulder, West Boulder, Stillwater, Smith and Dearborn rivers.

In addition to protecting more Wild and Scenic Rivers as a part of the 5,000 Miles of Wild campaign, together with River Network, the River Management Society, Partnership Wild and Scenic River groups, and nearly 50 other groups nationwide we have also launched a new coalition to build greater public support for protecting more rivers and building greater capacity for our groups to advocate for river protection. Over the coming year we will be advocating together for Congress to protect more rivers as Wild and Scenic and provide for financial support to take care of the Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

We also worked with filmmaker Shane Anderson and Pacific Rivers which produced Run Wild, Run Free, a film about the passion and people protecting rivers as Wild and Scenic. Check it out if you can.

So what’s next?

There are over 1,200 miles of new Wild and Scenic designations moving their way through Congress that could be protected as soon as this year or early next. This includes nearly 500 miles of rivers flowing in the Wild Olympics in Washington, nearly 400 miles of northwest California’s remaining free-flowing rivers and streams including the Trinity and Eel River watersheds as well as over 150 miles of streams along the central coast, and 120 miles of the York River and tributaries in Maine.

River communities in several states are hard at work advocating for new Wild and Scenic protections that, based on my experience, I am confident will lead to designations in the near future. These include Deep Creek in Colorado, New Mexico’s Gila and San Francisco Rivers; rivers in the Greater Yellowstone and Crown of the Continent in Montana, the Nolichucky in North Carolina and the Nooksack in Washington State.

Finally we are advocating for thousands of miles of new administrative Wild and Scenic River protections as a part of the development of new management plans for our public lands across the country. In California U.S. Forest Service is finalizing plans right now that will protect at least 720 miles of eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers including strongholds for the rare Golden Trout, the California state fish on the Inyo, Sequoia and Sierra National Forests. Check out this great video to see how you can get involved.

With all of the energy around Wild and Scenic Rivers there are many opportunities get involved. Help us reach 5,000 Miles. Tell your river story, get involved in a local campaign, or start your own for your backyard river.

I sneak into the back of a crowded lecture room at Flathead Valley Community College in Kalispell, MT. I’m about two minutes late (as usual) and hoping that everyone is too fixated on the facilitator and first slide of the evening’s power point presentation to notice my tardiness. Fat chance. In the time it takes me to find a seat, I’ve already met eyes with about a half dozen folks I’ve come to know so well over the last few years. A couple of raft company owners, fishing guides and outfitters, other conservation colleagues, riverside landowners and friends alike, all shoot me warm smiles and nods of hello from their places in the room. I am late, but I belong here.

I’ve been conducting outreach in the Flathead Valley for the past five years, building relationships between American Rivers and local businesses, conservation organizations, and every interested stakeholder in between. These relationships have helped me understand just why folks love the three forks of the Flathead River, and what exactly Wild and Scenic designation has meant to their lives. This understanding is helpful for me as I can continue to build support for new Wild and Scenic River protection in the Crown of the Continent and elsewhere in Montana. That work aside, the Flathead National Forest has been working to update its Comprehensive River Management Plan (CRMP) for the three forks of the Flathead River (the North, Middle and South forks) that were designated as Montana’s first Wild and Scenic rivers back in 1976.

Before your eyes glaze over, hang with me for a minute.

One of the many benefits of federal Wild & Scenic River designation is that following designation, a CRMP must be written to identify all of the Outstandingly Remarkable Values (ORVs) of that river or rivers, as well as specific management recommendations that will ensure those ORVs are maintained for future generations. Development of CRMPs is the responsibility of the federal agency that manages the land through which Wild and Scenic rivers flow. In the case of the three forks of the Flathead, both the Flathead National Forest and Glacier National Park manage the land within these river corridors. When the three forks of the Flathead were originally designated, CRMPs were not a requirement. It wasn’t until an amendment was made to the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in the late 1980s that CRMPs were required. The existing CRMP for the three forks of the Flathead was written more than two decades ago, so an update to the plan is long overdue.

It’s break time at the meeting and I get up to stretch my legs and give a proper hello to my Flathead friends. Enthusiastic hugs are exchanged between some folks I haven’t seen for months and some I just saw last month. We talk about our summer plans, river trips we are going to take, and how we think the meeting is going. Everyone is generally pleased with the chance to be here and participate. And this is why the CRMP is so important and should matter to you. These planning processes happen but once in a generation, and as your elders will tell you, not many places are the same as they used to be. The whole point of a CRMP is to monitor and plan for change, to develop thresholds and triggers for the things we care about most, whether that’s scenery, fisheries, water quality or recreation. Each of these river values is identified and dissected in the CRMP. Over the course of 2018, the Flathead National Forest and Glacier National Park hosted a series of public meetings to solicit input and feedback from the public. This “scoping” process is an agency term for gauging concerns and interests from stakeholders, and is a legally required component of plan development.

After a year and a half of public meetings, the Forest Service and Park Service released their “Proposed Action” or draft plan for the three forks of the Flathead in July. As an American Rivers staffer and someone who holds the three forks near and dear, the draft felt incomplete. For the abundance of ORVs that exist on the three forks, most were addressed only superficially, and some not at all. Potential future threats and management actions were not identified. We expressed many of these concerns in our American Rivers Northern Rockies office comments to the Forest Service last week. And I’m pleased to say that many of my friends and colleagues in the Flathead submitted comments as well, citing similar omissions.

I have never written a CRMP before, so I can only imagine what a daunting task it must be for the federal agencies. But after the years I have spent in the Flathead valley getting to know the rivers and people that make it so special, I believe there is just the right combination of community support and bright minds at the helm to ensure that a truly comprehensive and forward thinking plan is created.

At the end of the meeting, I say my goodbyes and shake hands with our agency friends, thanking them for holding this process and listening to us. In an administration that has proven to care little about protecting our natural heritage on the national stage, it’s comforting to know that the river managers in the Flathead care a whole lot.

If you have the chance to participate in a CRMP process, I hope you do. It’s democracy at work, and your chance to be a part of something that will live on long after you do. If you haven’t yet weighed in the three forks of the Flathead planning process and would like to, it’s not too late. Sign up for alerts to get the latest news and notices of future meetings. The CRMP is still in the draft phase, and while we at American Rivers believe that it needs to be bolstered considerably, it can’t fall just to the agencies to make that happen. Let’s all do what we can to create a plan that we can all be proud of so when it’s the next generation’s turn to update it, they have the chance to protect the same river values that exist on the Wild and Scenic three forks today.

Around the world, communities are experiencing the impacts of our changing climate. In the last two or three years, more frequent and dangerous extreme weather events like devastating wildfires, destructive flooding and crippling drought have caused unprecedented damages to communities, threatened public health and wellbeing, and weakened local economies. Not only does climate change impact local communities, but the rising temperatures, droughts, floods, and impacts to water quality threaten the health of rivers across the country.

While the impacts of climate change are being felt by communities across the country and around the world, the science behind why these changes are happening is less understood. In this episode of We Are Rivers, we explore the science of how greenhouse gas emissions are affecting climate change. While the topic isn’t purely focused on rivers, it is river related: climate change is intimately connected not just to the health of our rivers, but to the health of every single natural process and ecosystem in the world.

Greenhouse gases are an essential part of what makes Earth inhabitable. Greenhouse gas molecules allow the sun’s light energy to pass through them when coming into the atmosphere, but then when the sunlight is re-emitted back out towards space as infrared heat energy the greenhouse gases trap some of this outgoing radiation, keeping our planet warm. But since the industrial revolution, the amount of greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere has increased preventing outgoing infrared radiation from escaping and causing Earth’s temperature to warm at a greater rate than what we experienced in the past.

Our climate is a complex system that responds to seemingly small changes in temperature. Scientists expect that if the concentration of greenhouse gases doubles compared pre-industrial levels, the earth could warm 5.4℉. While this may not sound like a lot, consider the extreme weather events we have experienced already with less than 2℉ warming, like massive hurricanes, outbreaks of tornadoes, and extreme flooding or heat waves. Former Science Advisor for President Obama, John Holdren has a great analogy for how to understand the impacts of seemingly small temperature increases on our climate. He says that much like our own bodies, when we have a 1 °F fever, we know it; when we have a 2 °F fever, we really know it. As our temperatures increase, the effects become more and more severe.

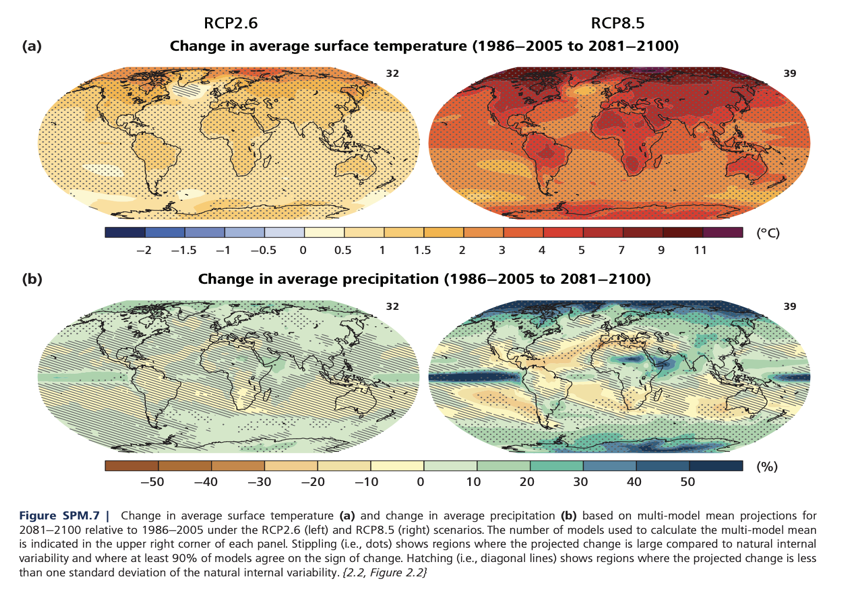

Fluctuations in the Earth’s climate are natural, but what we are experiencing today is not. There are pronounced changes in the climate system worldwide: deep ocean temperatures have increased along with sea surface temperatures, ice sheets are melting at an ever-increasing rate, and there’s more water vapor in the atmosphere. These are all undeniable markers of a warming climate, and the extent of these changes are well outside expected natural variability.

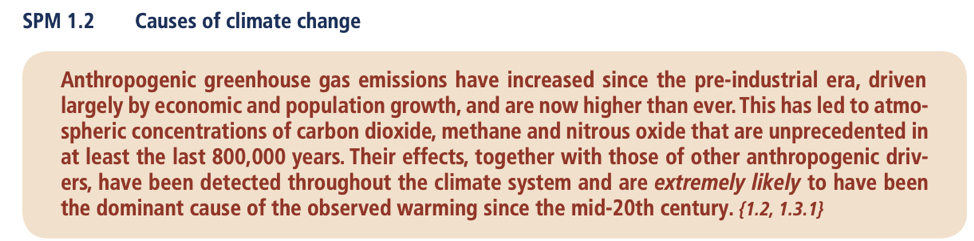

The scientific community has been instrumental in understanding the cause of climate change and what we might expect in the future. An intergovernmental panel of climate scientists from around the world is tasked with issuing official statements regarding climate change, and there is consensus among them about the extensive role anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are playing in global warming.

The Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC), was founded in 1988. Since their creation, the panel has issued five different assessment reports, each composed of three different sections with several hundred scientists working on each section. Reports are reviewed by many governments and processes before getting published, and the IPCC’s official statement on human greenhouse gasses, as of 2015, is as follows:

Climate change is happening all around us, and it’s our responsibility to understand how and why we are experiencing these effects and the role humans have. Join us in this episode of We Are Rivers, as Brad Udall, climate scientist, explains climate change and addresses some common questions about our changing climate. From the concepts and questions covered in this podcast episode, you will gain greater understanding and insight about how this broadly-accepted scientific understanding is creating challenges for communities, economies, and ecosystems all around the world.

Join us, as we dive into Episode 21 of We Are Rivers as we discover the science behind what is increasingly happening all around us.

Rivers across the country are constantly facing challenges— their fates often in the hands of regulators or other decision-makers. People wonder what they can do to influence these decisions. Do decision-makers care what the public thinks? Well, some do.

Every year, American Rivers highlights threats to rivers across the country in our annual report on America’s Most Endangered Rivers®. In 2019 and 2017, we listed the Buffalo National River on this list. The public told the decision-makers that they didn’t want their water contaminated with hog waste. And guess what? They listened. You can read the story here.

Right now is your opportunity to let us know what rivers you think are threatened. Do you think that your favorite river is facing a critical decision in the coming year? Have you been wondering… why isn’t my river on the list when it faces so many threats? Let us know!

We are excited to announce that we are now accepting nominations for our 2020 report. Nominations are welcomed from any interested groups throughout the United States.

Rivers are selected based upon the following criteria:

- A major decision (that the public can help influence) in the coming year on the proposed action

- The significance of the river to human and natural communities

- The magnitude of the threat to the river and associated communities, especially in light of a changing climate

The report highlights ten rivers whose fate will be decided in the coming year, and encourages decision-makers to do the right thing for the rivers and the communities they support. The report is not a list of the nation’s “worst” or most polluted rivers, but rather it highlights rivers confronted by critical decisions that will determine their future. The report presents alternatives to proposals that would damage rivers, identifies those who make the crucial decisions, and points out opportunities for the public to take action on behalf of each listed river.

Please help us make the most of this great opportunity in 2020 by nominating a river you think deserves to be included on our list. We are especially interested in highlighting threats this year which impact marginalized communities (although this is not a requirement for nomination).

Deadline for nominations is Friday, November 1, 2019. For more information or a nomination form, contact us at outreach@americanrivers.org.

This blog was written by Gerrit Jöbsis and Janae Davis.

It takes a village to raise a child. The same is true for making rivers and their communities more resilient to flooding and climate change. No single action or one party creates a more robust river. Resiliency comes from a community of partners in purposeful collaboration on many initiatives.

Collective efforts to build resilience along Waccamaw River in South Carolina exemplify communities coming together to reduce flood risks, protect critical floodplains and save money for residents.

Ravaged by hurricanes and recurring floods the communities of Horry and Georgetown Counites recognize that business as usual just won’t cut it when it comes to addressing the challenges being faced today. American Rivers’ partners are stepping up in different ways to address all too frequent flooding.

The City of Conway and Horry County are getting people out of harm’s way by leveraging FEMA funding that allows the purchase of repetitively flooded properties to relocate willing homeowners out of flood prone areas and reduce their vulnerability. These properties are at risk of flooding because they lie within floodplains; natural systems that store floodwaters and filter pollutants. Once purchased and after the homeowners have relocated, the municipalities remove the structures, returning the land to a natural state and benefiting the floodplain.

This is where another partner has stepped in. The Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge has agreed to take over the management of several of these properties once the structures are removed and the land restored. The 35,000-acre Refuge lies at the confluence of the Waccamaw and Pee Dee Rivers and includes parts of Horry County and the City of Conway. It is managed for wildlife, recreation and natural ecosystem values. An estimated 98 billion gallons of flood water were stored on Refuge lands during record flooding caused by Hurricane Florence in September 2018. This natural solution helped spare downstream communities in Georgetown County from the extreme flooding that occurred upstream.

The Refuge is also stepping up to make the area more resilient through a minor boundary modification that will allow 6,600 acres of land to be added to this federal preserve. The lands include those American Rivers helped identify along with municipal governments, federal agencies and other conservation organizations through a science-based assessment of lands. These lands help safeguard the area from sea level rise and flooding caused by climate change. The Refuge protects 152 acres of riverfront property purchased by the City of Conway and conservation partners, ensuring an additional buffer against flooding.

Horry County has worked hard to improve its floodplain management, increasing flood resiliency along the Waccamaw River. The County succeeded in improving its rating with the national flood insurance program lowering homeowner’s flood insurance rates and saving ratepayers over a half million dollars per year. They succeeded by working with the Waccamaw River’s floodplain as part of a nature-based solution that reduces flood risk and conserves riverside lands for recreation and wildlife habitat.

Communities along the Waccamaw River understand that working together and investing in floodplain resiliency is the best way to address flooding and increase defenses against climate change impacts. Clearly, these natural solutions and common-sense measures reduce risk and save money. Partners recognize that everyone’s contributions make the area safer from floods and that natural solutions are the key to their success.

In September of this year, as we tracked Hurricane Dorian’s path of destruction in the Bahamas, Charleston, South Carolina and Ocracoke Island, we are reminded that there is still much to be done to manage risks and make communities more resilient to natural disasters. As communities, we can come together, as the Waccamaw area did, to find ways to protect life, property and infrastructure from hurricanes, floods and other severe weather events.

President Trump’s first term is winding down, and the final year of any presidential term sees a flurry of proposed rules and other regulatory actions that seek to cement that president’s vision and legacy. Unfortunately, the legacy of an administration that tasked the likes of former Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator Scott Pruitt and former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke as the stewards of our environment and natural resources was never likely to be one of strong protection for rivers and clean water and wise stewardship of our natural resources.

In fact, the fire sale of regulatory proposals coming from EPA, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other agencies threatens to upend decades of progress in protecting and restoring water quality, wetlands, and endangered species. These proposals would undermine our most important environmental laws including the Clean Water Act (CWA), the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). But we can tell EPA, the Corps, and USFS that whatever they’re selling, we’re not buying!

Here are a few of the terrible deals on offer:

The EPA/Corps final rule repealing the Obama Administration’s Clean Water Rule that affirmed the Clean Water Act’s jurisdiction over small streams and wetlands is due to be released soon. Soon after, a new rule is expected which will roll back protection for small streams and isolated wetlands across the U.S., stripping federal protection from an estimated 18% of streams and half of the nation’s wetlands currently protected by the CWA. When these rules hit the street, American Rivers and our partners will file suit in federal court to block them. Click here for more information.

The Trump administration issued final rules undermining the implementation of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), curtailing protection for threatened species, bringing economic considerations into listing decisions that should be based solely on science, and strictly limiting consideration of climate change (!) in species listing and protection decisions. These changes were proposed under former Secretary Zinke and are coming to fruition under his successor, David Bernhardt, a long-time oil and gas lobbyist with a long history of antagonism to the ESA. The conservation community is gearing up to fight this in Congress and in court. American Rivers will work with our partners to ensure that the many fish and river-dependent wildlife under the Act’s protection have a champion in the fight.

Youth Climate Strike, Washington DC | Photo by Liam McAuliff

The EPA recently published a proposed rule that would severely curtail the authority of states and tribes under Clean Water Act section 401 to affect federal dam, pipeline and other infrastructure construction and operations through state water quality certifications. This authority is extremely important to states and tribes as it provides their citizens (all of us) a powerful say in federal infrastructure planning and licensing processes. American Rivers has worked with states and tribes on many occasions to improve dam operations, fish populations, and river health using section 401, and we have defended this authority all the way to the Supreme Court. Keep an eye out for an action alert that will provide you with an opportunity to make your voice heard on this important issue!

NEPA requires that federal agencies review the environmental effects of their projects and evaluate alternatives that might have a lesser impact on the environment and natural and cultural resources. As part of that review, the public is afforded ample opportunity to evaluate and comment on agency data and decision-making. This common sense, look-before-you-leap law has resulted in hundreds of potentially destructive federal projects stopped or modified to mitigate their impacts on the environment. The Trump administration is seeking to subvert NEPA through regulations to limit its scope and decisions that simply ignore its requirements. A recent proposed NEPA regulation from the U.S. Forest Service would wall-off much of national forest management decision-making from public scrutiny, eliminating transparency into decisions potentially affecting the water supplies of 66 million Americans. American Rivers is fighting NEPA roll-backs on multiple fronts. See here and here for more information.

On rare occasions you can find a real bargain at an everything-must-go sale, but often what’s on offer is just a lot of junk that nobody wants. Let’s let the Trump administration know that the regulatory rollbacks, lawless development, increased pollution, degraded wetlands, and lifeless rivers it’s selling belong in the dumpster.

Removing one obsolete dam is an accomplishment. Removing more than 30 in one year is unheard of.

Yet, that’s exactly what Cleveland National Forest (CNF) did in 2018. They removed 33 dams, which accounted for more than 40% of all dam removals in the United States in 2018. These removals are part of a broader effort CNF is leading to restore migratory corridors for fish and other aquatic species known as the Trabuco District Dam Removal Project. When complete, it will result in the removal of 81 dams that are no longer serving a purpose. In 2018, California had the highest number of removals, surpassing Pennsylvania, the leading dam removal state for the past 15 years.

How did they do it?

The Forest’s success is largely due to their ambitious approach to National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) compliance. The CNF identified dams and other instream barriers as inhibiting stream health, passage for aquatic species, and public safety hazards, and rather than expending resources thinking about each structure individually, they took a watershed-scale approach and evaluated the removal of all 81 dams within Silverado, Holy Jim, and San Juan Creeks within a single environmental assessment (EA).

Cleveland National Forest | Photo by US Forest Service

Dam removals that require a Clean Water Act Section 404 permit or are funded by federal dollars trigger one of three NEPA review processes that vary in review time, level of effort, and depth of analysis. Of the three, a Categorical Exclusion (CE) is the least rigorous, followed by an Environmental Assessment (EA). An Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), the most rigorous process, is generally required only for complex projects with potentially significant environmental impacts. As the level of analysis required by NEPA increases, so does the planning workload for federal staff and any consultants working on the project. This has ramifications on both the project timeline and budget.

Evaluating restoration and removal of the 81 dams in a single EA greatly reduced the time to complete NEPA and cost the Forest roughly $75,000. Additionally, having only one environmental assessment afforded the CNF flexibility in the timing and removal methods for individual dams.

The Trabuco District Dam Removal Project is well-suited for this programmatic approach given the size and proximity of targeted dams as well as their shared characteristics. The dams slated for removal were all small barriers concentrated on four nearby creeks within the Trabuco Ranger District. Nearly all were built or rebuilt by Orange County in the 1970’s to create pools for stocked rainbow trout, conserve water and wildlife, and provide water for fire suppression. This continuity made it easy to lump the dams into one cohesive project.

We also have a strong understanding of the anticipated benefits and impacts associated with dam removal as a river restoration tool. In areas where many small dams are scattered throughout a watershed, the full benefits of dam removal—improved fish passage, enhanced stream habitat, and restored natural stream processes— increase exponentially when project proponents can address multiple dams within the system. This makes the Cleveland National Forest’s approach necessary from a restoration standpoint and efficient from the permitting standpoint.

For other organizations looking to remove multiple dams, Kirsten Winter, the Forest Service biologist managing the project, recommends the programmatic approach for its efficiency and advises building in as much flexibility as possible regarding timing and removal methods. According to Winter, “This has been a great project and has built many partnerships for the Forest. There is a huge interest in dam removal and many partners are willing to fund this type of work for mitigation or just for habitat improvement.”

What’s next?

New approaches to permitting have the potential to speed the pace of dam removal on federal lands. A 2014 amendment to the Forest Service NEPA regulations added three new categorical exclusions, including modifications to water control structures, which includes dam removals. The new rule, which allows National Forests seeking to remove a dam to complete a Categorical Exclusion rather than a more arduous EA or EIS, increases the efficiency of dam removal projects while still maintaining public involvement and environmental protection.

Cleveland National Forest | Photo by USFWS

The Pacific Northwest Region (Region 6) of the U.S. Forest Service is also looking to increase the pace of aquatic restoration by taking an analogous, but slightly different approach to that used by the Cleveland National Forest. They are evaluating a region-wide environmental assessment on Forest Service land in the Pacific Northwest covering a suite of aquatic restoration techniques, including dam removal, rather than addressing specific projects. The premise for this, much like in the CNF, is that the restoration activities selected are ones in which the impacts and benefits of said projects are a known entity and can be predicted.

Hopefully, these alternate paths, along with the “many dams, one NEPA” strategy employed by the Cleveland National Forest will lead to more dam removals on federal land and improve the health of rivers nationwide.

For more information about the Trabuco District Dam Removal Project, contact Kristen Winter, Cleveland National Forest, 858-674-2956, kwinter@fs.fed.us

Hurricanes are getting stronger and flooding is becoming more frequent and severe. More than 100 dams breached in recent years in South Carolina and North Carolina because of hurricanes and flooding. These devastating storms take lives, destroy property and cause hundreds of millions of dollars in damages. Historically marginalized communities and communities of color often suffer the worst impacts, thanks to generations of systemic inequities.

So what are we doing to protect ourselves? On the plus side, champions including state Sen. Dick Harpootlian scored a win for public safety by defeating misguided legislation that would have exempted two-thirds of dams in South Carolina from safety standards.

In addition, Gov. Henry McMaster created the South Carolina Floodwater Commission to support public dialogue and encourage solutions for alleviating and mitigating flooding in coastal and river communities.

This is positive progress, but we must keep pushing for more. We need a major paradigm shift in how we value and manage our rivers. In order to protect communities, the Palmetto State must embrace five critical priorities:

- Get people out of harm’s way: Poor planning has enabled development in flood prone areas, putting people in harm’s way. Where possible, we should compensate willing sellers and restore natural areas that can absorb floodwaters and buffer homes and businesses from damages. The property buy-outs and restoration happening on the Waccamaw River are a good example of how federal funds can assist these efforts.

- Protect and restore floodplains: Floodplains are the natural, low-lying areas along rivers. Naturally functioning floodplains store and absorb floodwaters and reduce downstream flooding. We need to take advantage of these natural defenses.

- Pass the South Carolina Resilience Revolving Fund Act: This bill establishes state funding for buyouts of flooded properties and supports floodplain restoration. Sens. Stephen Goldfinch, Chip Campsen, Marlon Kimpson, Sandy Senn and Paul Campbell led the charge to get this bill through the Senate in 2019. The House of Representatives and Gov. McMaster must make passing this bill and signing it into law a top priority for 2020.

- Strengthen state dam safety laws and programs: Recent dam failures make it clear that our current standards, especially for dams in the Sandhills and Coastal Plain which are by far the most likely to fail, do not provide the level of safety we need to match the reality of today’s extreme flooding. With more than 2,300 regulated dams in the state, it’s time to confront this threat.

- Remove dams that do not meet safety requirements: We cannot wait until dams fail to take action. Poorly maintained and improperly designed dams that are not brought up to standard need to be removed to protect downstream communities and infrastructure before they fail.

The choice is ours. Our action — or inaction — will determine whether our rivers become corridors of destruction, or whether they will be lifelines to safer, more secure communities.

Rivers in South Carolina have always been an integral part of our heritage, our identity and our way of life. Now, they hold the key to our safety, and our future.

This op-ed originally appeared online on the www.thestate.com on June 13, 2019.

Since 2009, American Rivers has worked tirelessly protect the Waccamaw River. We’ve partnered with numerous organizations across North Carolina and South Carolina to provide greater access to the river and its recreation opportunities through the Waccamaw River Blue Trail. Much of the Trail flows through the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge, a 55,000-acre stretch of critical riverside lands set aside to protect important wildlife like the swallowed-tailed kite, coastal black bear, the red-cockaded woodpecker, and a wide variety of rare plants.

Waccamaw River | Photo by Gator Bait Adventure Tours

The Refuge allows countless photographers, kayakers, fishers, and hikers, history enthusiasts, birders, and naturalists to enjoy the beauty of the Waccamaw. In addition to providing unmatched opportunities for recreation that benefit the regional economy, riverside lands assure clean drinking water for local communities and reduce flooding to homes and businesses caused by increased hurricane and extreme rainfall events. American Rivers and our partners have been at the forefront of efforts to promote all of the benefits the river provides to both people and wildlife by supporting Refuge.

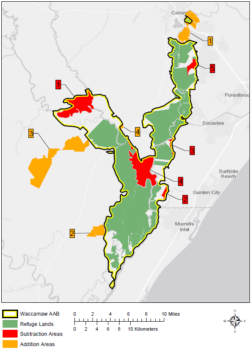

This week, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service released a proposal to change the boundary of the Refuge. The minor boundary modification will support the Refuge’s mission to promote the health of the river, its surrounding forests and the many benefits they provide for wildlife and communities.

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

It will remove 6,849 acres of land from the Refuge which no longer provide proper wildlife habitat due to local activities that have permanently changed the landscape. These areas are shown in red on the map. The current boundary will be changed so that 6,638 new acres, shown in yellow, will be added to the Refuge through the purchase of properties from willing landowners. These additional lands harbor critical habitat that will help local wildlife withstand the effects of climate change, improve public access to the river, enhance recreational opportunities, and support clean drinking water and flood protection.

The Waccamaw River is a lifeline for North Carolina and South Carolina, and is critical to the region’s economy, environment, lifestyle, and health of local communities. With a changing climate, growing population, and competing needs for water, protecting the Waccamaw River and its surrounding lands is more important than ever. The minor boundary modification is an opportunity to improve the resilience of local wildlife, provide additional opportunities for recreation for residents and visitors, and safeguard the wellbeing of communities along the Waccamaw River.

I encourage you to act now! We only have 30 days to voice our support for the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge minor boundary modification. Take a moment to let the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service know that you support the boundary modification and want to protect the Waccamaw River.

This blog was compiled by American Rivers Summer Interns Clara Silverstein and Berit DeGrandpre.

August marks the conclusion of American Rivers summer internship program. While American Rivers intern placements and their responsibilities are diverse, they all share a deep connection to the organization’s mission. Interning is a fantastic way to learn more about how nonprofits operate, develop lifelong skills and make a meaningful contribution to the goals of American Rivers.

Hear from the Summer 2019 interns about various aspects of their internship experience from learning to why they love rivers!

Addie Ewalt, Philanthropy Intern in Denver, CO, on a how she grew during the internship:

During my internship with American Rivers, it has been somewhat challenging to learn how to work with such a disbursed team and function remotely as a team member since I’m not in the Washington, DC headquarter office. I find that having team members in multiple states is really great for perspective and influence towards the organizations mission; however, sometimes working so far away from the rest of the team – it can feel like I am struggling to find my place and communicate regularly with everyone. I am always learning when I work on a new project with or for someone outside Colorado, which is definitely a positive aspect of being a remotely based intern. The minor challenges I have faced while working here feel insignificant to compared to the positive and very rewarding experience I’ve had as a part of the American Rivers team.

Avi Young, Legal Intern in Washington, DC, on his favorite river:

My favorite river is the Connecticut River! One of the best experiences of my life was kayaking down this river for 5 days with 12 friends. This was the first kayaking trip I had ever been on, and I completely fell in love with kayaking. My arms were sore for days after, and I received the worst sunburn of my life, but it was still one of the best experiences of my life. I am proud and fortunate to work for an organization that works tirelessly to protect rivers, so others can have similar experiences to my own.

Berit DeGrandpre, Foundation Relations Intern in Washington, DC, on something unexpected she learned:

Berit DeGrandpre | Photo by Cathy Yi

Since starting my internship at American Rivers, I’ve been blown away by the amount of people and resources that it can take to thoroughly execute a single conservation project. In the same vein, this has highlighted the incredible career diversity within the conservation field. One conservation project requires specialized conservation staff, as well as legal counsel, development and fundraising support, finance and accounting expertise, media and marketing strategies and countless other components that aren’t always obvious when looking at the face value of a single project. There are so many passionate people that contribute in their own various ways to a single dam removal or river restoration project. This process has been a really fulfilling thing to observe and be a part of.

Caitlyn Cook, Legal Intern in Washington, DC, on how she will use the skills she’s learned at American Rivers:

Working in the legal department, I learned to dive straight into whatever I was tasked with, no matter how unfamiliar or daunting. Applying the skills I’ve learned in school to accomplish real life objectives, that themselves lead to positive environmental impacts, has been an amazing experience. I now feel a confidence in my work and skills that I did not have previously and feel that I am ready to tackle whatever my next assignment will be!

Caroline Watson, River Conservation Intern in Durham, North Carolina, on why she chose an internship at American Rivers:

I am passionate about making sure that everyone has enough clean water to drink, which I believe starts with rivers. I also wanted to learn how integrated water management is applied to ongoing projects in North Carolina. My interest in the connection between rivers and drinking water was a perfect fit for American Rivers’ mission to protect, restore and conserve rivers as natural resources. I chose to do an internship at American Rivers to support their mission to conserve our drinking water supply and learn more about responsible water management.

National Arboretum | Photo by Cathy Yi

Clara Silverstein, National River Cleanup® and Corporate Relations Intern in Washington, DC, on the office culture:

The first thing I noticed when I got to the DC Headquarters of American Rivers was the office decoration — fly fishing poles, canoe paddles, and river maps everywhere. I love that the passion everyone shares for the work they do is so visible. Although I have almost walked into a hanging fly rod once or twice, they are a fun reminder of the joy that rivers bring to so many people.

Daniela Galeano, Urban Water Intern in Atlanta, Georgia, on a defining moment in her internship:

During my internship at American Rivers, I have been able to assist with Finding the Flint. Finding the Flint is a project created by American Rivers, The Conservation Fund, and The Atlanta Regional Commission to restore The Flint River’s headwaters and revitalize surrounding communities. Finding the Flint has been an incredible project to be a part of and valuable experience. Core partners have rallied around a central goal of involving not only environmental experts and Atlanta officials but have also been devoted to welcoming community members’ ideas and concerns. A memorable moment for me was speaking with community members at a Finding the Flint event. It was so inspiring to see their desire to improve their environment and their willingness to collaborate with American Rivers and each other. I hope to continue learning from this team and carry experiences with me in future endeavors.

American Rivers hosts interns throughout the year. Please visit the Careers and Internships page to learn about current opportunities!