In an era when Americans have become accustomed to hearing about disastrous environmental rollbacks on a weekly basis, we’re happy to share some good news out of Montana

On July 9, the Custer Gallatin National Forest released an updated forest plan that provides key protections for 30 Wild & Scenic eligible rivers totaling 253 river miles. That represents a 150 percent increase in the number of rivers protected and a 45 percent increase in the number of river miles protected compared to the existing forest plan that was written in the mid-1980s.

Every 30 years or so national forests update their forest plans, which guide management decisions for decades to come. Rivers that are deemed to be eligible for designation under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act are required to receive protections for the life of the forest plan from projects that would alter their free-flowing nature, clean water or outstanding values, such as scenery, recreation, fish and wildlife.

Many of the waterways that will gain new protections are located on the northern fringe of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, one of the last intact temperate ecosystems in Earth. All of them are critical for sustaining fisheries, clean water, and outstanding recreational opportunities such as fishing and paddling. Some notable rivers that will receive protections for the first time include the West Boulder River and West Fork Stillwater River. Hyalite Creek, which provides drinking water for the City of Bozeman, will also receive new protections.

While this updated forest plan is generally good news for river lovers, the Forest Service left out a handful of magnificent waterways that deserve protection. The most glaring example is the Taylor Fork, which flows into the Gallatin River just south of the resort community of Big Sky. The Taylor Fork is home to one of the only native Westslope cutthroat trout fisheries in the Madison Range and a place cherished by hikers, horse-packers, anglers, hunters and paddlers. It also harbors one of the densest populations of grizzly bears in the lower 48 states and serves a migration corridor for elk making their way from Yellowstone National Park to the Madison Valley.

The new forest plan also highlights an urgent need to permanently protect some of Montana’s most cherished rivers. For years, American Rivers has been working with our partners at Montanans for Healthy Rivers to pass the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act through the United States Congress. If passed, this Wild and Scenic Rivers bill would permanently protect 17 rivers and streams totaling 336 stream miles, including such gems as the Taylor Fork and Gallatin, Madison, Yellowstone and Smith rivers.

American Rivers greatly appreciates the Custer Gallatin National Forest for taking action to provide needed interim protections for many of our special rivers. Now, we need your help to tell Montana’s congressional delegation that now is the time to permanently protect the rivers we love.

Two minutes of your time can go a long way. Please TAKE ACTION today!

Historically, Colorado has had a love-hate relationship with the 1968 Wild & Scenic Rivers Act. While we have unarguably some of the wildest and most scenic rivers in America, Colorado has only one such designated section – the Cache la Poudre River above the city of Ft. Collins. New Jersey, a much smaller state with many fewer river miles, has five designated Wild & Scenic Rivers.

So why? The reason lies in the both real and perceived limitations such designation would place on how water is “developed,” and its various uses, across the state, including potential limitations on longstanding diversions for municipal and agricultural water needs. Unlike New Jersey, Colorado is an arid state where water is precious, and rivers often have been regarded as natural conduits for delivering and storing water that can be diverted and used, rather than as natural systems that need freedom and nurturing to thrive.

The Colorado River is a prime example, as the most over-tapped and heavily diverted river in the state.

Yet In 2007, the Bureau of Land Management and White River National Forest found the upper Colorado River, just downstream from its source in Rocky Mountain National Park as “eligible” for designation as a part of the Wild and Scenic River system. This finding alarmed the Front Range water providers, who siphon large amounts of water across the continental divide to the cities and farms of the East Slope. It is commonly said that “80% of Colorado’s water falls as snow on the West Slope, while 80% of the people live on the East Slope.” The last thing Front Range water providers have wanted was another layer of federal restrictions that could curtail their ability to move more water to thirsty cities in the metropolitan corridor.

There has long been strong support for Wild & Scenic River designation from conservation groups and others on both sides of the divide. These efforts would help protect what are called Outstandingly Remarkable Values, or ORVs, which qualify a river as eligible for protection. ORVs may be related to fish, wildlife, geological, or recreational values. Now, in this newly emerging recreation economy, these ORV’s are the backbone of some of the States’ most important and valuable draws to tourism, recreation, and rural lifestyle. More recently, Front Range diverters have recognized the importance of these ORV’s not just to the West Slope headwater communities, but to the State as a whole. The recreational opportunities and businesses depending on white water rafting and fishing are a huge economic asset. The fact that this all exists within a series of beautiful and remote canyons doesn’t hurt either.

Over the past 12 years, a group of people involved in the upper Colorado was established to try and develop a plan, and later an associated process, to protect the various values of the river, along with West Slope economic needs, while retaining flexibility for Front Range water users. What emerged from this effort was a multi-stakeholder plan to protect the river while addressing each of these needs, and establishing metrics for evaluating the condition of the ORV’s along with a process for resolving potential problems, should the river begin to show increasing signs of stress. While taking considerable effort by everyone involved, the process is working.

In 2015, the BLM and Forest Service recognized this process as an alternative to a “suitability finding” for Wild & Scenic designation. This sparked a five year “provisional period” where all the interested parties could come back to the table to hammer out a final management plan. There was light at the end of the tunnel to help give the river the protection it deserves, while providing certainty for existing and future water users. If the collaborative planning failed, the Upper Colorado River would retain its eligibility status and would have to undergo another suitability study.

The provisional period wrapped up in June with the adoption of the final, agreed-upon plan to evaluate, mediate, and provide solutions to protect the various values of the upper Colorado River, from the town of Kremmling all the way to Glenwood Springs.

This plan is a “living” document, and will be for some time. For instance, work is still being done to finalize a plan to collect, analyze, and monitor data over a longer period for fish, insects and sediment levels. An endowment fund is providing long-term financial support, to continue to discuss topics around governance, finance, scientific monitoring, and other cooperative measures to regularly check-in on progress to keep the Plan working, and stakeholders accountable.

The Wild & Scenic Stakeholders Group and resulting plan is not far from a traditional, Federally authorized Wild & Scenic designation. The newly Amended and Restated Plan provides a detailed process for cooperative monitoring and management of the ORV’s. All of the stakeholders are committed to making sure the Plan succeeds.

It has taken 12 long years to get here, and the work certainly continues. The stakeholders have gotten to know each other, and most importantly have built a rapport of trust and engagement with one another. Yet with the overarching goal of protecting the upper Colorado for a wide variety of uses, while providing certainty and good health for the river itself, the efforts put into this process will benefit everyone involved for decades to come.

This is a guest blog by Eric Kuhn, former General Manager and a member of American Rivers’ Science and Technical Advisory Committee and author of “Science Be Dammed, How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River.”

As Utah pushes forward with its proposed Lake Powell Pipeline – an attempt move over 80,000 acre feet per year of its Upper Colorado River Basin allocation to communities in the Lower Basin – it is worth revisiting one of the critical legal milestones in the evolution of what we have come to call “the Law of the River.”

The division of the great river’s watershed into an “Upper Basin” and “Lower Basin”, with separate water allocations to each, was the masterstroke that allowed the successful completion of the Colorado River Compact in 1922. But the details of how that separation plays out in water management today were not solidified until a little-discussed U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1955, in the early years of the decade-long legal struggle known as “Arizona v. California.”

Most, if not all, of the small army of lawyers, engineers, water managers, board members, academics, tribal officials, NGO representatives, and journalists now actively engaged in Colorado River issues are familiar with the 1963 Arizona v. California Supreme Court decision. It was Arizona’s great legal victory over California that cleared the road for the Congressional authorization and construction of the Central Arizona Project (CAP). Many in the ranks are also quite familiar with Simon H. Rifkind, the court-appointed Special Master who conducted lengthy hearings and worked his way through a mountain of case briefs and exhibits before writing his 1960 master’s report that set the stage for the court’s decision. Few of us, however, are familiar with George I. Haight. Haight was the first special master in the case, appointed on June 1st, 1954. He died unexpectedly in late July 1955. Two weeks before his death he made a critical decision that was upheld by the Supreme Court and set the basic direction of the case. Today, as the basin grapples with climate change, shortages, declining reservoir levels, and most recently, Utah’s quest to build the Lake Powell Pipeline exporting a portion of its Upper Basin water to the Lower Basin to meet future needs in the St. George area, Haight’s forgotten opinion looms large.

In late 1952 when Arizona filed the case, it was about disputed issues over the interpretation of both the Colorado River Compact and the Boulder Canyon Project Act. Among its claims for relief, Arizona asked the court to find that it was entitled to 3.8 million acre-feet under Articles III(a) & (b) of the compact (less a small amount for Lower Basin uses by New Mexico in the Gila River and Utah in the Virgin River drainages), that under the Boulder Canyon Project Act California was strictly limited to 4.4 million acre-feet per year, that its “stream depletion” theory of measuring compact apportionments be approved, and that evaporation off Lake Mead be assigned to each Lower Division state in proportion to their benefits from Lake Mead. California, of course, vigorously opposed Arizona’s claims. One of California’s first moves was to file a motion with Haight to bring into the case as “indispensable” parties the Upper Division states; Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. California’s logic was that the compact issues raised by Arizona impacted both basins and every basin state (history has shown California was right on).

The Upper Division states were desperately opposed to participating in the case. Backing the clock up to the early 1950s, these states, including Arizona, had successfully negotiated, ratified, and obtained Congressional approval for the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact. They were now actively seeking Congressional legislation for the Colorado River Storage Project Act (CRSPA), the federal law that would authorize Glen Canyon Dam (Lake Powell) and numerous other Upper Basin projects. Upper Basin officials feared that if they became actively involved in Arizona v. California, California’s powerful Congressional delegation would use it as an excuse to delay approval of CRSPA (as it had successfully done with the CAP). Thus, these states and their close ally, Arizona, opposed California’s motion.

The basis of their opposition was relatively simple; Under the compact, except for the Upper Basin’s obligations at Lee Ferry, the basins were separate hydrologic entities, the issues raised by Arizona were solely Lower Basin matters, and that Arizona was asking for nothing from the Upper Division states. Their strategy worked. In a July 11, 1955 opinion, Haight recommended California’s motion be denied. By a 5-3 decision, the Supreme Court upheld his recommendation and, except for Utah and New Mexico as to their Lower Basin interests only, the Upper Division states were out of the case. The Upper Division states cheered the decision. Arizona’s crafty Mark Wilmer devised a new litigation strategy built on Haight’s logic and ultimately his successor, Simon Rifkind, ruled that there was no need to decide any issue related to the compact. For more details, see Science Be Dammed, Chapter 15.

In convincing Special Master Haight to deny California’s motion, Arizona and the Upper Division states turned him into an ardent fan of the Colorado River Compact. Haight opined “The compact followed years of controversy between the states involved. It was an act seemingly based on thorough knowledge by the negotiators. It must have been difficult of accomplishment. It was the product of real statesmanship.” In justifying his decision, he found “The Colorado River Compact evidences far seeing practical statesmanship. The division of the Colorado River System waters into Upper and Lower Basins was, and is, one of its most important features. It left to each Basin the solution to that Basin’s problems and did not tie to either Basin the intra-basin problems of the other.” A few pages later, he says “The Compact, by its terms, provides two separate groups in the Colorado River Basin. Each of these is independent in its sphere. The members of each group make the determinations respecting that group’s problems,” and finally “because by Article III of the Colorado River Compact there was apportioned to each basin a given amount of water, and it is impossible for the Upper Basin States to have any interest in water allocated to the Lower Basin States.”

Fifty five years later, how would Special Master Haight view the problems the Colorado River Basin is facing where climate change is impacting the water available to both basins, through the coordinated operation of Lakes Mead and Powell the basin’s drought contingency plans are interconnected, critical environmental resources in the Grand Canyon, located in the Lower Basin, are impacted by the Upper Basin’s Glen Canyon Dam, and most recently two states, New Mexico and Utah, have found it desirable to use a portion of each’s Upper Basin water in the Lower Basin? With one major exception, I think he would be pleased. Haight understood that through Article VI, the compact parties had a path to resolve their disputes and implement creative solutions. The first part of Article VI sets forth a formal approach where each state governor appoints a commissioner, the commissioners meet and negotiate a solution to the issue at hand and then take the solution back to their states for legislative ratification. This formal process has never been used, but luckily, Article VI also provides an alternative. The last sentence states “nothing herein contained shall prevent the adjustment of any such claim or controversy by any present method or by direct future legislative action of the interested states.” After Arizona refused to ratify the compact in the 1920s Colorado’s Delph Carpenter successfully used federal legislation to implement a six-state ratification strategy (the Boulder Canyon Project Act).

The exception that would concern Haight is Utah’s unilateral decision to transfer about 80,000 acre-feet of its Upper Basin water to the Lower Basin via the Lake Powell Pipeline. The LPP violates the basic rationale that Haight used to keep the Upper Basin out of Arizona v. California and for which Utah and its sister Upper Division states fought so hard. The project uses water apportioned for exclusive use in the Upper Basin, terms carefully defined by the compact negotiators, to solve a water supply problem in the Lower Basin.

Defenders of Utah’s may believe a precedent has already been set– the Navajo-Gallup Pipeline, which delivers 7,500 acre-feet of New Mexico’s Upper Basin water to the community of Gallup and areas of the eastern Navajo Nation. But if that is to be cited as a precedent, it comes with an important caveat. New Mexico addressed the compact issues through federal legislation with the participation and consent of the other basin states and stakeholders. Utah, by comparison, apparently believes federal legislation, and by implication the consent of others in the basin, is not needed.

In the face of climate change induced declining river flows and increased competition for the river’s water, there is no question that the basic compact ground rules devised by the negotiators a century ago will face increasing pressure. There will likely be more future projects and decisions that, like the LPP, will challenge the strict language of the compact. The question now facing the basin is how will this revisiting be accomplished? Will it be done in an open and transparent manner that engages not just the states, but a broad range of stakeholders and implemented through legislation (not easy in today’s world, as a practical matter it requires no opposition from any major party to get through the Senate) or by a series of unilateral decisions designed to benefit or advantage individual states or specific entities, but with no input or buy-in from the basin as a whole?

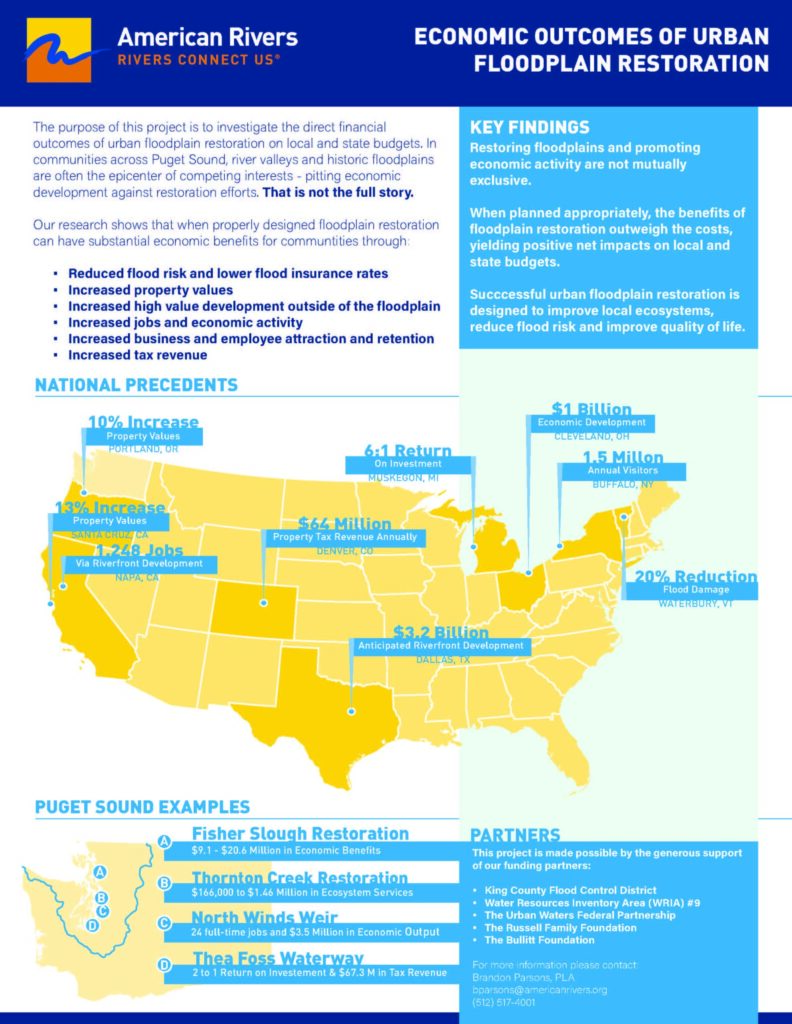

Restoration funding in the Puget Sound and across the country is generated from tax revenue. Over 50% of Washington’s revenue comes from sales, business & occupancy and property tax. Preliminary estimates show the state could lose $7 billion in revenue due to COVID-19 – potentially resulting in deep cuts across the board, including a decrease in restoration funding as salmon and Southern Resident orca populations continue to decline and flood risk intensifies. While COVID presents unprecedented challenges, funding shortfalls are common in the state budget and competition for funding is fierce. Moving forward, it will be even more essential for policy makers to understand the revenue implications of their funding decisions and invest in programs that will accomplish multiple benefits while showing a high return on their investment.

Similarly, local communities must be increasingly strategic about how to invest their limited resources to provide the most benefit to their residents. In urban communities, river valleys and their historic floodplains are often the epicenter of competing interests. Decades of floodplain development have replaced healthy habitat with industrial, commercial and residential development – degrading the environment and cutting off many communities from their greatest natural resource. These impacts disproportionately effect low income communities where access to clean water and open space are already more limited.

In their natural condition, these same areas would provide critical flood protection to communities and are essential to the recovery of the Puget Sound salmon and the Southern Resident orcas that depend on them. They would also provide important educational, recreational, and health benefits if they were publicly accessible. However, now many communities get a substantial portion of their tax revenue from their river valleys, forcing a perceived trade-off between restoration and economic growth.

The two are not mutually exclusive.

American Rivers believes that it is essential, now more than ever, to illuminate these economic outcomes of urban floodplain restorations so that families across the country can rediscover their rivers and communities can make smarter and more equitable land use decisions in the future.

A recent report on the Economic Outcomes of Urban Floodplain Restoration by American Rivers, ECONorthwest, and Environmental Sciences Associates (ESA) compiles examples from around the country on the direct financial benefits of urban floodplain restoration on local and state budgets. The report demonstrates that there is a substantial economic benefit when communities invest in floodplain restoration, through:

- reduced flood risk and lower flood insurance rates;

- increased property values;

- increased high-value development outside of the floodplain;

- increased jobs and economic activity;

- increased business and employee attraction and retention; and

- increased tax revenue.

The goal of this report is to illuminate the economic outcomes of investing in urban floodplain restoration as we work to reduce our flood risk, restore salmon populations, increase equity and grow our economies in an increasingly constrained and stressed environment. Our intent is that the results of this study will serve as a resource for communities as they make decisions about the highest and best use of their land in a way that balances healthy, functional rivers and economic growth. Although the geographic focus is the Puget Sound region of Washington, the findings of this report are broadly applicable to locations across the county with similar perceived tensions between floodplain restoration and urban development or communities interested in obtaining the highest economic return as they invest in their river corridors.

Generous financial support for this project was provided by the King County Flood Control District, Watershed Resource Inventory Area (WRIA) #9, the Urban Waters Federal Partnership, The Russell Family Foundation, and the Bullitt Foundation

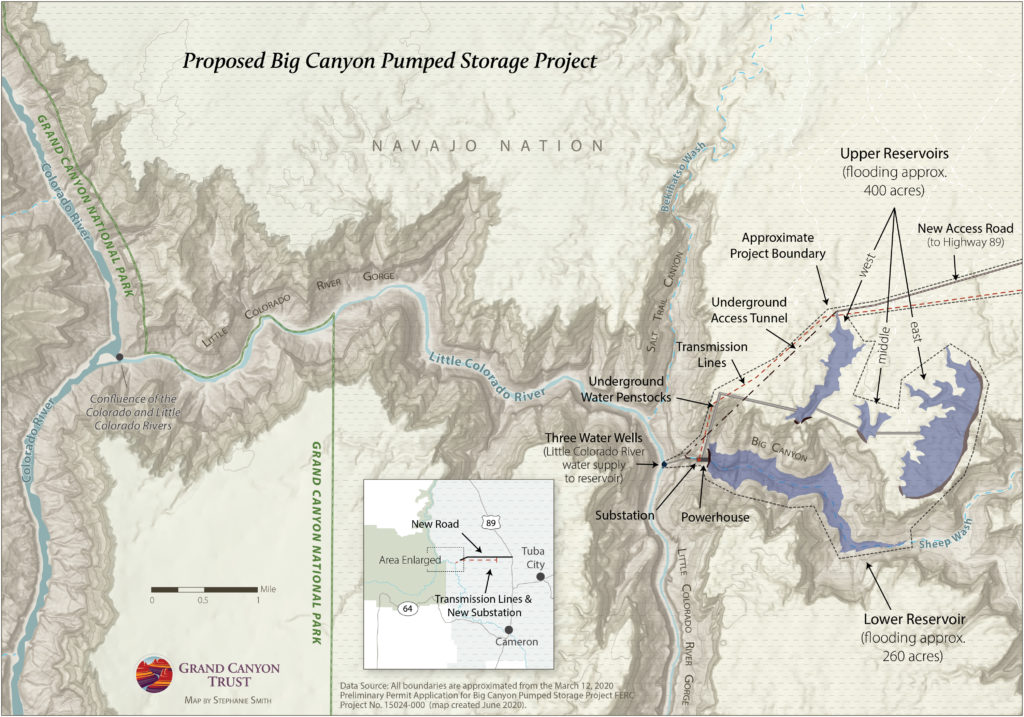

As we wrote in October, a Phoenix-based developer has proposed to build a pumped hydropower facility on and above the Little Colorado River in Arizona, one of the major tributaries to the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. Because this is an energy-related project, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) is the federal agency that would permit the project. The developer, Pumped Hydro Storage, LLC, actually applied for preliminary permits for two complete projects within the canyon, holding their place in line for two possible locations in the same area.

In November, we filed our comments with FERC, opposing the projects on a number of grounds. First and foremost, the idea of building new dams, reservoirs, and other related infrastructure (imagine the pipes, wires, roads, and other structures needed for such a facility) on such a major tributary of the Colorado River would be a destructive, resource intensive, and in all likelihood, impossible, endeavor. Secondly, the facilities would be situated firmly within the Navajo Nation, on Navajo land – yet the Navajo were barely even consulted on the project prior to the permit applications being submitted to FERC, and have since come out strongly against the projects being built on their lands, and very close to one of the most significant cultural sites to the Hopi as well. Lastly, the Little Colorado River is home to a major humpback chub recovery project, a fish on the brink of being down-listed from Endangered to Threatened due to the success of the program.

Including from American Rivers, the proposal generated a wide body of opposition from sources who don’t often speak out against projects like this, such as the Bureau of Reclamation and Department of Interior, multiple Tribal Nations and the two local Navajo Chapters in the area, multiple conservation groups, and even Arizona’s Department of Game and Fish. Basically, nobody outside of the developer feels that these projects are warranted, or even a very good idea, let alone feasible.

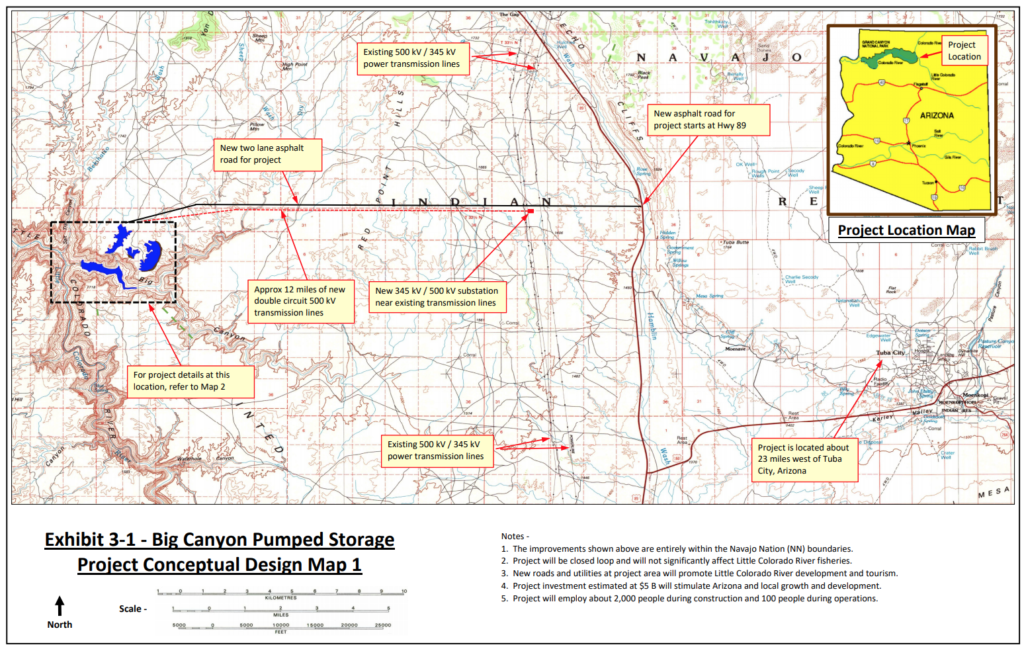

Now, Pumped Hydro Storage has applied for a new project with FERC (Permit 15024-000), which would be located not within the Little Colorado River, but in Big Canyon, a tributary to the Little Colorado about 23 miles west of Tuba City, Arizona. Unlike the original proposal, in this new one Pumped Hydro Storage is proposing to extract groundwater, bring it to the surface where it would rest in three different surface reservoirs, and build a fourth, lower reservoir and a variety of pipes and penstocks and other infrastructure to generate electricity. Here is how it is described in the permit application:

The proposed project would be located entirely on Navajo Nation land and consist of the following new facilities:

- A 450-foot-long, 200-foot-high concrete arch dam (Upper West Dam)

- A 1,000-foot-long, 150-foot-high earth filled dam (Middle Dam)

- A 10,000-foot-long, 200-foot-high concrete arch dam (Upper East Dam)

- each of which would impound three separate upper reservoirs with a combined surface area of 400 acres and a total storage capacity of 29,000 acre-feet of water

- A 600-foot-long, 400-foot-high concrete arch dam (Lower Dam) that would impound a lower reservoir with a surface area of 260 acres and a total storage capacity of 44,000 acre-feet of water

- Three 10,000-foot-long, 30-foot-diameter reinforced concrete penstocks;

- An 1,100-foot-long, 160-foot-wide, 140-foot-high reinforced concrete powerhouse housing nine 400-kilowatt pump-turbine generators

- And a whole lot more associated infrastructure, including a new 15-mile paved road, powerlines, a 30-ft diameter tunnel, and more.

Finally, an additional twist, as reported in a recent Associated Press article, the developer concedes that there was overwhelming opposition to his original proposal, and that he would consider pulling the proposals in the Little Colorado River if this Big Canyon proposal were allowed to move forward. From the article:

“Pumped Hydro Storage LLC recently applied for a preliminary permit for a project adjacent to the river on the Navajo Nation. Manager Steve Irwin said the shift was in response to overwhelming criticism that building dams on the river would disrupt the habitat of the endangered humpback chub.”

The article then goes on to say:

“But Irwin said he won’t pursue the dams on the river if the Big Canyon proposal moves forward. Documents filed with the federal government estimate the project will cost between $10 million and $20 million for studies, tests, surveys and maps, and to construct four earthen and concrete dams that would hold back groundwater.”

Many of the reasons that Pumped Hydro Storage, LLC’s initial proposal shouldn’t move forward apply to this new proposal as well; namely that the project would be built on Navajo Nation lands, and neither the local Chapter, nor the Navajo Nation government, have given their permission to construct the project on their lands. Second, the idea of pumping significant volumes of groundwater from one of the most arid regions of the country to profit from cheap electricity is misguided, at best. And just like the first round of proposals, destruction of significant Hopi holy sites, as well as threatening critical humpback chub and other fish habitat, through the massive extraction of local groundwater, is simply not acceptable.

In addition to how environmentally destructive and wasteful these projects are, this proposal is especially tone-deaf and exploitive at this moment in our history. The Navajo Nation is grappling with some of the highest number of cases, and deaths per capita, from the novel Coronavirus pandemic. One of the reasons why the outbreak has impacted the Navajo so heavily is the lack of readily available clean water. In fact, in the western Navajo Nation, the lack of basic infrastructure to deliver water to people’s homes is sorely lacking, and most of the people in that area have to haul water themselves many miles to have any at all. The idea of building expansive infrastructure to extract scarce groundwater for a hydropower project that extracts the resource and the capital from it, when people around the project who lack that access to that very resource are working hard to defend their communities against a deadly virus, could not be more misguided.

It is important to understand that a preliminary permit only allows the developer to hold a location for a potential future proposal. It is not a license application. In fact, a preliminary permit is not even required to submit a license application or receive a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) hydropower license. To learn more about hydropower licensing, visit the Hydropower Reform Coalition’s website.

We will intervene, again, in the FERC preliminary permit process, but you too can help by taking action here.

While it is unlikely that this project will ever advance past this phase, proposals like this underscore the importance of permanently protecting our last, best rivers like the Little Colorado.

The Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest released its new forest plan last week, and river lovers have plenty to celebrate. The new forest plan protects 45 Wild and Scenic eligible streams, 361 stream miles and more than 115,000 acres of wildlife-rich riverside lands. This is nearly triple the number of stream miles protected under the 1986 forest plan and great news for everyone who loves free-flowing rivers, healthy fisheries, and clean water.

By law, the U.S. Forest Service is required to periodically update forest plans that guide management decisions on every national forest. As a part of this process, the Forest Service identifies streams that are eligible for protection under the Wild & Scenic Rivers Act. While only Congress can designate new Wild & Scenic rivers, waterways that are deemed eligible for designation must be protected in their current state for the life of the forest plan, which is about 30 years.

Among the cherished waterways that will receive administrative protections under the new forest plan are the Dearborn River and forks of the Sun River and Teton River along the Rocky Mountain Front, as well as the Smith River and Tenderfoot Creek. The latter two waterways are included in proposed Wild & Scenic legislation called the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act. This legislation would protect 17 rivers and streams totaling 336 river miles in the Upper Missouri and Upper Yellowstone river systems.

Montanans from across the political spectrum understand that permanently protecting our state’s free-flowing rivers and clean water is critical to our state’s future economic prosperity and outdoor way of life. Last March, a statewide public opinion poll commissioned by the University of Montana found that 79 percent of Montanans support the proposed Montana Headwaters Legacy Act.

For the last decade, American Rivers has been working with our partners at Montanans for Healthy Rivers to build support for protecting Montana’s wild rivers and streams. With your help, we hope to have this proposed Wild & Scenic legislation introduced in Congress by this summer.

June is National Rivers Month, and American Rivers is teaming up with NRS, Orvis and Under Solen Media to break down barriers to the outdoors. We’re following Faith Briggs and Adam Edwards as they share their adventures and lead conversations about making the outdoors safe and accessible for all.

Learn more about #JustAddWater

We hope you’ll join us!

You can register for these free film screenings and Q&A events by signing up on the #JustAddWater page:

Conversation 1 – Online premiere of Water Flows Together, a story about Colleen Cooley, a female Navajo river guide and her deep kinship with indigenous lands and the San Juan River, which flows along the edge of Bears Ears National Monument. Followed by a Q&A with Colleen and Sinjin Eberle from American Rivers.

Conversation 2 – Online premiere of Una Razón para Pescar (A Reason to Fish). Dan Diez’s passion for fishing is rooted in a story — a story about Dan and his grandfather — that involves traditions born in Cuba, the search for a new home, and a relationship with water that symbolizes a freedom often taken for granted. Followed by a Q&A with Simon Perkins from Orvis, Amy Kober from American Rivers and Katie Guerin from City Kids.

Conversation 3 – Online premiere of River of Return. For Sammy and Jessica Matsaw, there is no divide between humans and the Earth. Their people, the Shoshone-Bannock, are part of the ecology of the Middle Fork of the Salmon River. Together, they are reintroducing indigenous youth and aim to restore equilibrium to their people and this place. Followed by a Q&A with Sammy and Jessica Matsaw of River Newe, Mark Deming from NRS and Amy Kober from American Rivers.

Conversation 4 – Screening of This Land, a story about land access told through a journey of inclusion and empowerment, followed by a Q&A film screening and Q&A on Thursday, June 4. Faith and Adam will be joined by Whit Hassett + Chelsea Jolly, the directors of This Land, Mike Fiebig from American Rivers, and Ángel Peña from Nuestra Tierra.

With parts of the country and the West slowly, tenuously re-opening, we know people are loading up trailers and trucks, putting air in tires and crafts, dusting off sun hats and heading out the door to visit places they miss, and do the things that make them feel whole.

But the world has changed, is indeed still changing underfoot, and in our desire to get back out there, the checklist of what to bring might be better served as a checklist of how we recreate in ways that are thoughtful and considerate not just toward the places we go, but the people we encounter there.

With that in mind, and in celebration of June as National Rivers Month, we compiled tips for recreating thoughtfully during a time when COVID-19 is causing stress for, well everyone, but especially front-line workers and small, rural communities at the gateway to popular recreation hotspots.

1) Consider Your Impact: This isn’t a new concept; for those of us who rely on wild lands and rivers for our well-being, we know how critical it is that we care for them—that we move consciously through them and measure our gains with the long-term impacts our presence may pose. That same ethos can serve us well in the time of COVID if we expand our lens to the gateway communities that often rely on places we love for revenue from tourism, and are also often rural, with limited health and emergency resources. It’s the job of every recreationist now (and perhaps always) to consider how their added presence in a place contributes or detracts from the community (or communities) that call that place their permanent home by knowing and respecting all local guidelines and restrictions for going out and recreating. And, of course, by following #6.

2) Forget the Parks: In a recent article for High Country News, Craig Childs wrote: “Forget the parks; seek out the spaces in between, the backyards and alleys. It’s a great time to explore an irrigation ditch or the woods at the edge of town — to see what’s around you…”. Let Craig’s charge serve as a challenge: what nearby plot of public land or stretch of river, back alley or small park, might not be “the best”, but that you could come to know without putting others, or yourself, at risk?

3) Stay Close (to home): In many states, recreationists are restricted in terms of how far they can travel to ride a bike or get on the water. In Colorado, for example, residents were encouraged to travel no more than 10 miles from home to recreate. Even as those restrictions change, and they will, we know that people visiting hotspots and then travelling home, or coming from a hotspot to a rural mountain town, is part of how the virus spread in the first place. Those places will remain (if we fight for them – see #7), and now is the time for patience.

4) Take Some Distance (from others): You can honor social distancing recommendations and still be out. Get creative. Consider small crafts, like packrafts or kayaks, rather than cramming big crews into one raft. Enjoy smaller groups of friends. Maybe take some alone time. Consider non-peak hours – set the alarm earlier, or take an off-hour lunch break. Maybe your new at-home schedule means you can recreate during the week days, and log Zoom calls on the weekends. Whatever the trick, keep away from the crowds, and when you can’t – wear a mask. Masks are more about keeping others safe around you than protecting yourself (think #1 here).

5) Look close, hold still: Writer Krista Langlois recently penned a piece called “The Beauty of Staying Still” for the Adventure Journal. In it, she argues for the intimacy that comes with slow, unstructured time spent in a place, and offers up an alternate way for understanding our current reality: “staying still doesn’t have to be a sentence. It can be a gift.”

6) If You’re Sick, Please: We probably don’t have to say it, but we will, because even if you think you’re being cautious, this wildly contagious virus is outmaneuvering our understanding of it. Even if you think “aha”, I’ll go solo, any encounter with people or the places they visit can put them at risk. Stay home and off the trail for at least two weeks. Rest. Get well. And, while you’re staying the course and making sure you don’t expose others, become a couch warrior for the places you can’t wait to visit once you’re able and allowed.

7) The Fight Goes On: Take some of the time at home to get educated, up-to-speed, and to advocate for the rivers and places you miss. They aren’t going anywhere, unless we let them. If we stay vigilant, those sanctuaries will still be there when we can visit again without putting communities and fellow humans at risk. When it comes to rivers, there are some things you can do at home, starting today. First, thank Senators Udall and Heinrich for introducing a bill to designate the Gila River in New Mexico as Wild & Scenic. Next, let’s protect our vital headwaters streams by opposing the rollback of the Clean Water Rule. Finally, discover how rivers act as an economic engine, for nearly every small town and city across the country.

Finally, don’t forget what rivers mean—all the ways they matter. Sure, they’re important for bringing you together with people care about. But they’re also timeliness in a way this pandemic isn’t. That gentle rocking of the boat, the technicolor reflection at last light, the soothing (or unnerving) churn of water in motion—those are things that have been and will be well beyond this pandemic. Lean into the memory and solace of them. Lean into each other. We’re all on this wild ride, this river, together—even if we’re in different boats.

The Chehalis River Basin, located in southwest Washington, is the second largest watershed in the state. The river and its tributaries provide spawning habitat for some of the only wild salmon runs in the state that are not protected under the Endangered Species Act, for now. The Chehalis watershed is also home to The Chehalis Tribe and the Quinault Indian Nation, many vibrant small communities and some of the most productive agricultural land in the state.

Decades of development in the floodplains of the Chehalis River and long-term logging in the upper watershed, coupled with climate change, is exacerbating major flooding resulting in impacts to communities, farms and even to Interstate 5, a major north-south transportation corridor.

Unfortunately, the Chehalis Basin Flood Control Zone District is proposing to build a massive dam on the Chehalis River to control flooding. The dam would severely threaten this ecosystem and degrade critical fish and wildlife habitat, while not effectively controlling flooding. The Office of Chehalis Basin is now accepting public comments on its Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the Chehalis River Basin Flood Damage Reduction Project.

American Rivers recognizes that flooding creates significant impacts for residents, towns, agriculture and transportation. The current and future problems from floods in the Chehalis Basin are a result of many decades of human building, land management, and transportation patterns. Two of the largest floods in the basin’s history occurred in 2007 and 2009 reigniting the need for wholistic ways to reduce flood risk. Climate change will result in more frequent and intense flooding events and larger flood damage if immediate and sweeping actions are not taken. Based on the modeling in the Draft EIS, the number of structures inundated during major flooding and catastrophic flood events by 2080 will remain incredibly high, even with the dam. And with an expected price tag of about $1 billion, this proposed dam on the Chehalis River will be a huge burden on taxpayers and deliver only minimal benefits to a small portion of the basin in return. Other places across the county have shown that flood control, habitat creation and community amenities can be integrated into the same projects and program – a good use of hard-earned taxpayer dollars. We need new out-of-the box solutions that don’t force unacceptable trade-offs for fish, wildlife and public safety.

With the recent dam failure in Michigan sweeping headlines, why would we as a society choose to build a dam on the Chehalis River in a location with hillslope instability? In addition to the Edenville Dam failure in Michigan, dozens of dams failed in the Carolinas five years ago. Thousands of residents were evacuated due to the partial failure of nation’s tallest dam, Oroville Dam on the Feather River, three years ago. These disasters aren’t specific to one region, they are impacting communities nationwide.

Take action by May 27 in opposition to the proposed Chehalis Dam. Based on the Draft EIS, it is clear that the dam, if it were to be built, would push the Chehalis River’s spring Chinook population to the brink of extinction and would further decimate the basin’s struggling steelhead population. In addition, hundreds of acres of quality forest, riparian habitat, and wetlands would be destroyed. Please take a minute to protect the Chehalis River’s people and wildlife from this misguided dam proposal. Together, we can create commonsense, fiscally-sound solutions that can meet the twin challenges of flood control and restoration.

Lastly, a new film by our colleague Shane Anderson with North Fork Studios and Pacific Rivers premiered on May 17. Chehalis: A Watershed Moment eloquently tells the story of the Chehalis Basin and the critical decisions we now have to determine its future. This hour long film is available to watch on You Tube.

Water has always been the architect of life in Colorado. Communities have worked within the availability, demands, and constraints of water to engineer lives and livelihoods. Water designs our lives as much by its availability as it does by scarcity—perhaps even more. In 2013, the State of Colorado recognized the impending impacts of rising populations, increasing demand across the state and the West, and a changing climate, then-Governor John Hickenlooper called for a plan to address these issues. He directed the Colorado Water Conservation Board—the government entity tasked with conserving, developing, protecting and managing the state’s water—to work with diverse stakeholders and develop Colorado’s first water plan. You can learn more about the Plan from Episode 6 in our podcast series.

In some ways, Colorado’s Water Plan articulated and formalized ways to meet the needs of agriculture, land use, and storage that were already in place. But it also did something else: for the first time, the Colorado Water Plan called for the consideration and integration of environmental and recreational flow needs. This decision came from growing recognition of the critical role rivers play in local economies, and the immense ecosystem services that healthy, functioning rivers and streams provide for all values—human and environmental. With this in mind, the Water Plan outlined a goal of inspiring community-driven development of Stream Management Plans for 80 percent of locally prioritized rivers and streams.

In the first episode of this miniseries, we hear from Nicole Seltzer, Science and Policy Manager of River Network, who talks us through the fundamentals of the stream management planning process. Holly Loff, Executive Director of Eagle River Watershed Council, shares on-the-ground experiences of a community planning effort along the Eagle River, and Chelsea Congdon-Brundige, a watershed consultant in the Roaring Fork Valley, shares her highlights from a similar but unique effort for the Crystal River.

As you’ll hear in the podcast, a critical component of Stream Management Planning is the diversity of stakeholders and interests at the table; the important and foundational role of science; and the way each Plan is unique to the community that builds it. SMP’s (as they’re often referred to) are really more about process than a final product, and the greatest win is the long-lasting trust inspired through tough but important conversations across values. SMPs aren’t designed to prioritize any one interest, but instead to bring agriculture, the environment, municipal needs, and recreation alongside one another for the best possible solutions for all.

Rio Grande Headwater Restoration Project

If you’re inspired by this first Episode, and we suspect you will be, make sure to tune in for part 2 (coming 6/1/20) . We’ll hear from some of the same voices and from new ones from the Rio Grande Basin – including Heather Dutton with the San Luis Valley Water Conservancy District and Emma Reesor with Rio Grande Headwaters Restoration Project – about the groundbreaking and inspiring ways communities are working together to plan for the future of the rivers and streams that bind them, and all of us, together. Join us – and listen in today!

A dam failed in Michigan yesterday, forcing thousands of residents to evacuate their homes. The Edenville Dam, which failed, and the Sanford Dam, which was compromised, are on the Tittabawassee River, a tributary of the Saginaw River. The failures followed days of heavy rainfall and sent floodwaters into downstream communities. Residents of Edenville, Midland and Sanford were evacuated.

A dam failure and a flood, in the middle of a global pandemic: it’s a worst-case scenario. The immediate focus needs to be protecting public health and safety. Governor Whitmer encouraged people to seek shelter with friends or relatives, and to take precautions to prevent the spread of coronavirus.

How did this happen?

Why did these particular dams fail? Was it because of heavy rains? Climate change? Faulty, aging infrastructure? Lack of action by the dam owner? Right now, we know the following:

- The Edenville Dam was plagued by concerns and safety violations. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission revoked its hydropower license in 2018 due to concerns that the dam could not withstand a significant flood. FERC flagged problems for the dam’s owner starting in 1999.

- Climate change is bringing more severe and frequent flooding at a time when our nation’s infrastructure is aging and outdated.

- The American Society of Civil Engineers has repeatedly given our nation’s dams a grade of D in their “Report Card for America’s Infrastructure” – citing age, downstream development, dam abandonment and lack of funding for dam safety programs. More dams will fail, endangering people and property, unless we act to repair essential infrastructure and remove dams that no longer make sense. The Association of State Dam Safety Officials estimates there are more than 2,000 high-hazard dams nationwide in deficient condition.

- The dam failure in Michigan isn’t the first “wake up call” when it comes to the need to address aging infrastructure. Dozens of dams failed in the Carolinas five years ago; thousands of residents were evacuated due to the partial failure of nation’s tallest dam, Oroville Dam on the Feather River, three years ago; and last year the Spencer Dam failed in Nebraska forcing evacuations. These disasters aren’t specific to one region, they are impacting communities nationwide.

Dale Kolke, CA DWR

While we’re still learning about the specifics of this disaster which is still unfolding in Michigan, the following three actions are necessary to protect communities in the future:

- Increase, don’t decrease, public safety and environmental safeguards – The safety of federally licensed hydropower dams is overseen by FERC. While FERC revoked the dam’s license in 2018 due to safety concerns, that clearly was not enough to prevent this week’s catastrophe. Moreover, on the same day the dams failed, President Trump signed a new executive order to roll back more regulations under the guise of restarting the economy. Further gutting the regulations that safeguard human lives and safety and protect the environment is the wrong way to produce a sustainable economic recovery.

- Strengthen evaluation and enforcement – Michigan has a working dam safety program. Even so, state dam safety offices are historically underfunded with a limited number of staff responsible for inspecting thousands of dams. We must improve these efforts by making it the responsibility of dam owners to inspect and maintain their dams; requiring more frequent, detailed inspections of deficient dams and increasing penalties for unsafe dams and violations; and, requiring dam owners to ensure that funds are available to repair or remove dams in the event they can’t or won’t meet safety standards. As communities continue to grow and development expands, many dams may also be misclassified as infrastructure and development increases downstream.

- Increase funding for dam removal and water infrastructure – Dam removal can be the best way to address a dam that poses a safety risk. There are tens of thousands of dams across the country that no longer serve the purpose they were built to provide and whose removal could eliminate the cost and liability associated with owning a dam. Unless they are well maintained, their condition only gets worse every year. The most cost-effective and permanent way to deal with obsolete, unsafe dams is to remove them.

Healthy rivers are the lifeblood of our communities and our environment, and we depend on essential infrastructure to provide water, power and other services. It’s time to prioritize river protection, and investment in smart infrastructure. Our communities, our economy and our lives depend on it.

If there ever was a river deserving of inclusion into the national Wild and Scenic Rivers system, the Gila River in Southwestern New Mexico is it. Thanks to the leadership of New Mexico Senators Martin Heinrich and Tom Udall, we have the opportunity to protect this amazing, historic watershed, permanently. Late last week, the Senators introduced the M.H. Dutch Salmon Greater Gila Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which would protect nearly 450 miles of the Gila and San Francisco Rivers and their tributaries under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the premiere federal river protection legislation in the United States.

“Dutch” Salmon was a self-described New Mexican “redneck environmentalist,” who spent his whole life fighting for the Gila and against harmful dams and diversions, until he passed away a little over a year ago. Dutch authored many books about the Gila including the seminal book, Gila Descending, about his 200-mile trip down the Gila with his hound dog and cat; it is only fitting that the Senators honored him with this bill.

I have traveled amazing wild rivers from Alaska to Florida, Maine to Arizona. One look at the Gila and you recognize the magic of its natural flow and exceptional beauty. The Gila is precisely what the framers of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, including Senator Udall’s father, Stewart Udall, had in mind when they set out to create a national system of protected rivers. In addition to passing the scenic eye-test, the Gila and its tributary, the San Francisco River, are full of other outstanding values. Geologically rich, the Gila is home to amazing box canyons, pinnacle rock formations, and numerous caves that supported the Mogollon culture – providing the rich cultural history still evident today through extensive rock art panels and intact cliff-dwellings.

Ecologically, the area is renowned for its high-quality bird habitat and populations of unusual species like the endangered Southwestern Willow Flycatcher, threatened Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Common Black Hawk, Montezuma Quail, and Elf Owl. The watershed is also a stronghold for the rare Gila trout and a major conservation strategy is underway to protect the fish from other, non-native species. American Rivers is working with the Senators to enable agencies to protect and restore Gila trout while preserving the free-flowing nature of the river.

The Gila is also full of both easily accessible and backcountry recreational opportunities – boating, hiking, hunting, fishing, essential fish and wildlife habitat, cultural richness, and on and on…supporting a vibrant and growing recreation-based economy that benefits Southwestern New Mexico in numerous ways.

Over the past several years, the Senators and their staffs have worked incredibly hard with the local community—listening, answering questions, and resolving any potential concerns. It’s been some time since there have been any Wild and Scenic designations in New Mexico (the most recent one was a 12-mile stretch of the Rio Grande in 1994!) and in my experience, this is exactly the kind of careful work to build understanding and durability for river protection that sets the example for locally-driven efforts across the country.

The Senators’ work builds upon the support of the local Grant County Commission, who voted late last year in support of Wild and Scenic River protections for the Gila River and its tributaries on nearby National Forest Service lands. The Commissioners, such as Chairman Chris Ponce, recognize the value the Gila provides its citizens both as a place of safe, free, family-friendly outdoor recreation, and as a growing source of economic benefits for Silver City, the gateway to the Gila, as it diversifies its economy.

Efforts of this magnitude and scope provide us an incredible opportunity, and Senators Heinrich and Udall deserve our help. Please take a minute to thank them for their leadership to protect the Gila as Wild and Scenic and about your love and appreciation of wild rivers.