Two summers ago, I floated the Middle Fork Salmon, in the heart of Idaho’s Frank Church–River of No Return Wilderness. The trip had everything, spectacular scenery, great fishing, wonderful companions. The only thing missing was abundant salmon and steelhead which, before the construction of the four lower Snake River dams, made the 800 mile journey from the ocean to the Middle Fork Salmon to spawn. I came away from that trip knowing that restoring this amazing migration is critical to the future of the Pacific Northwest and our nation.

Communities across the Pacific Northwest have been in crisis for decades, feeling the pain from dwindling salmon runs. These iconic fish once filled our rivers, sustaining native tribes and powering local economies dependent on fishing, recreation and tourism. At the same time, infrastructure across the region is aging and our rivers and water quality face ongoing threats. The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified problems, adding new stresses for families and communities, exposing inequities and forcing many businesses to close their doors.

The challenges facing salmon and communities are urgent and require bold solutions. That’s why we welcome a groundbreaking proposal announced by Congressman Mike Simpson (R-ID). In a new video, he outlines a plan to revitalize the rivers and economy of the Pacific Northwest. The $33.5 billion package of infrastructure investments would advance salmon recovery, clean energy, agriculture and economic opportunity regionwide, and honor treaties and responsibilities to Northwest tribes.

The proposal’s river investments include:

- Restoring the lower Snake River in southeast Washington through the removal of four federal dams

- Water quality improvements in the Columbia Basin, Puget Sound, and Washington and Oregon coasts

- Restoration of salmon in currently blocked areas in the upper Columbia and upper Snake rivers

- Funding for the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan

- Incentives to remove select fish-blocking dams in the Columbia Basin

- Increasing tourism and recreation opportunities

You can read Congressman Simpson’s proposal here. There are a host of benefits for the region, including the restoration of the lower Snake – what would be the biggest river restoration effort in history. But there are also elements that require more conversation. For example, the framework includes wide-ranging restrictions on the application of federal environmental laws and extensions of licenses for hydropower dams throughout the entire Columbia Basin. In creating a path to restore rivers and salmon, we must not grant a broad license for other environmental harms.

American Rivers is committed to working with Congressman Simpson and the entire Northwest congressional delegation to make this package as beneficial as it can be for our rivers and communities.

A legacy of collaboration

Congressman Simpson’s fresh thinking and comprehensive approach builds on a legacy of collaboration in the region.

From the Yakima to the Owyhee, the Pacific Northwest has a track record of crafting innovative, bipartisan solutions to challenging water and river issues. Governors Inslee and Brown, and Senators Murray, Cantwell, Merkley and Wyden have supported these efforts in the past and they have a critical role to play now.

As Congressman Simpson says,

“The question I am asking the Northwest delegation, governors, tribes and stakeholders is “do we want to roll up our sleeves and come together to find a solution to save our salmon, protect our stakeholders and reset our energy system for the next 50 plus years on our terms?” Passing on this opportunity will mean we are letting the chips fall where they may for some judge, future administration or future congress to decide our fate on their terms. They will be picking winners and losers, not creating solutions.

We can create our own solution on our own terms.”

Economic benefits for the region and the nation

Congressman Simpson’s proposal is also an example of how investing in healthy rivers can be a down payment on a future of abundance and prosperity. A well-crafted, comprehensive solution would not only benefit the Northwest, but the nation as a whole by restoring salmon runs, bolstering clean energy and strengthening the economy of one of the most dynamic regions in the country.

Our Rivers as Economic Engines report details how investing in smart infrastructure and healthy rivers can revitalize local economies.

Salmon – and people – need healthy rivers

For decades, Northwest tribes have been spearheading salmon recovery solutions in the Columbia-Snake and regionwide. The Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) adopted its first resolution advocating for removal of the four lower Snake River dams in 1999.

In a statement last year, Chairman Shannon F. Wheeler said, “We view restoring the lower Snake River as urgent and overdue. To us, the lower Snake River is a living being, and, as stewards, we are compelled to speak the truth on behalf of this life force and the impacts these concrete barriers on the lower Snake have on salmon, steelhead, and lamprey, on a diverse ecosystem, on our Treaty-reserved way of life, and on our people.”

In his video, Congressman Simpson says, “My staff and I approached this challenge with the idea that there must be a way to restore Idaho salmon and keep the four lower Snake River dams. But after exhausting dozens of possible solutions, we weren’t able to find one…In the end we realized there is no viable path that can allow us to keep the dams in place…I am certain if we do not take this course, we are condemning Idaho salmon to extinction.”

At American Rivers, we’ve seen dam removal work on rivers nationwide. More than 1,700 dams have been removed in our country, restoring free-flowing rivers and revitalizing river ecosystems. From Maine’s Penobscot River to Washington’s Elwha, White Salmon and most recently the Middle Fork Nooksack, American Rivers has helped spearhead successful dam removal and river restoration efforts.

We need your voice: speak up for a comprehensive solution

Big problems require big solutions – and the Pacific Northwest has always been a place of big ideas.

American Rivers applauds Congressman Simpson for tackling this region’s interconnected challenges. This is a historic opportunity to invest in what makes the Northwest strong. Congressman Simpson has given us a great place to start.

President Biden took steps to make Americans more resilient to climate change and the increasing floods that many communities are facing by signing an executive order that directs federal agencies to considering reversing harmful environmental actions taken under the previous administration. In addition to restoring National Monuments like Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante and revoking the permit for the Keystone XL Pipeline, this sweeping executive order reinstated the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard — a key step toward improving protection and management of the nation’s floodplains.

In our 2021 Blueprint for Action, American Rivers called on the Biden-Harris Administration and Congress to reinstate the standard, which requires federally funded infrastructure to be built to a higher standard that is safer and more resilient to floods. It also urges all federal agencies to use nature based solutions wherever possible.

Higher flood standards mean safer, more resilient communities.

The United States has been wrestling with increasingly severe floods for decades. As flood damage rises, so does the federal cost of flood response and recovery. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter took steps to protect federal taxpayer investments, public safety and river health from flooding when he signed an executive order that required federal agencies to avoid actions or development in the 100-year floodplain whenever practical.

By 2015, it had become clear that the so-called “100-year flood” was no longer an adequate measure of flood safety if communities were to be resilient to the more frequent and intense floods brought by climate change. As a part of his Climate Action Plan, President Barack Obama established the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard. This standard required that federal projects must be able to handle a larger flood and steps were taken to make sure that agencies had as much flexibility as possible to use a standard that works for their projects. The standard offers three options:

- Climate-Informed Science Approach: Agencies use the best-available science to determine future flood conditions — design infrastructure and buildings accordingly.

- Freeboard Evaluation Approach: This approach takes the 100-year flood and adds 2 feet of “freeboard.” Infrastructure and buildings must be able to handle this larger flood. For critical facilities like hospitals, the standard is raised to 3 feet of freeboard for an added margin of safety.

- 500-Year Elevation Approach: This approach requires that infrastructure and buildings be able to handle the 500-year flood, i.e., the flood that has a 0.2 percent chance of occurring in any given year.

Encouraging nature-based solutions.

In an important move for the health of rivers, the standard also states that, “Where possible, an agency shall use natural systems, ecosystem processes, and nature-based approaches when developing alternatives for consideration.” This key policy was the first interagency instruction to all federal agencies that they should use nature-based solutions in floodplains whenever possible.

Nature-based solutions to flooding — such as restored wetlands, reconnected floodplains, natural floodways and natural vegetation — are generally more resilient, sustainable and cost-effective than traditional static, concrete strategies alone. They also beautify and provide quality of life and economic benefits to communities.

Nature-based solutions have been growing in popularity and support from communities across the nation in recent years thanks to their ability to solve multiple challenges for communities. For agricultural areas trying to reduce excess nutrient runoff into rivers and streams, restoring floodplains can improve water quality and give rivers room to safely flood. Upgrading undersized culverts and bridges to accommodate a larger flood also improves passage for fish and other river critters. And breaching levees can allow fish to access spawning and rearing grounds, while the flooded floodplain captures carbon and recharges groundwater supplies. Nature-based solutions can even bring economic benefits and revenue to local cash-strapped communities.

An error gets corrected.

Despite the clear benefits of the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard to communities across the country, the previous administration revoked the standard in 2017. Just days later, Hurricane Harvey hit the Gulf of Mexico, bringing devastating flooding to Texas communities.

By reinstating the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard, the Biden-Harris administration is sending a clear signal that science is a priority, and that administration will aggressively push to ensure that American communities are increasing their resilience to flooding and climate change. This is a start for President Biden, but it is just the first step toward implementing equitable, integrated flood management and prioritizing nature-based solutions in states and communities across the country. American Rivers is eager to work with the Biden-Harris administration to take additional steps to improve protection and management of the nation’s floodplains.

This blog was written by Julie Fair and Daisy Schadlich

During the summer of 2020, American Rivers and partners completed the restoration of three small meadows in the Upper West Walker River Watershed. The meadows – Upper Sardine, Lower Sardine, and Cloudburst – are located at around 8,500 feet in elevation on the east side of Sonora Pass in the Eastern Sierra.

Historic land use, especially unregulated grazing, resulted in degradation in these three meadows. Heavy grazing can result in soil compaction and erosion that can be self-perpetuating. When meadows are degraded, they are less resilient and therefore more prone to further damage. A large flood event in 1997 exacerbated the effects of grazing in these meadows, resulting in erosion and gullies that were unnaturally draining the meadows. In addition, in Lower Sardine Meadow, flow from an adjacent hillslope was being concentrated into culverts under Highway 108 rather than spreading flow across the meadow surface. This further contributed to meadow drying and erosion.

Yosemite Toad

These meadows are unique in part because Upper and Lower Sardine provide breeding habitat for Yosemite Toad, a federally threatened species. These toads are very particular about their breeding habitat; they depend on shallow ponded water at high elevations. Snowmelt from the surrounding peaks pools in the wet meadows in the spring and early summer. After breeding, adult toads move to upland areas where they overwinter in animal burrows. Juveniles mature quickly and are out of their ponds in a matter of weeks. They then move to the wooded upland to fill up on food and find a burrow before the colder weather comes.

Dryer meadows mean less intact habitat for Yosemite Toad and other species that depend on healthy, wet meadow systems. Additionally, Lower Sardine had a historic dirt road cutting through the meadow that threatened Yosemite Toad habitat. Toads were known to breed in the tire ruts of the road in the springtime, and although the road was formally closed by the US Forest Service, it was still being used by off-highway vehicle users, sometimes squishing young toads.

Restoration

American Rivers worked with our partners to decommission 580 feet of the old dirt road and construct 660 feet of new walking trail to reroute people away from sensitive Yosemite Toad breeding habitat. The project also placed dirt and rock to fill gullies, arrest erosion, protect toad habitat and restore the meadows’ ability to provide natural water storage. In addition to these enhancements, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) installed two new culverts under Highway 108 at Lower Sardine meadow to restore more natural flow to the meadow surface.

Photo by Julie Fair

restoration | Photo by Julie Fair

One culvert at Upper Sardine Meadow was too steep for toads to climb out of when they followed the flow upstream in their transition, leaving them stranded in the pipe. To fix this, Caltrans installed a low-angle ramp that allows the toads to climb out of the culvert and access upland habitat on the other side of the highway.

In total, the project repaired 2,500 feet of eroded channels and swales and restored and protected 38 acres of wet meadow. American Rivers has been working with the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest and California Trout, with help from Forest Creek Restoration, since 2018 to restore these sites. The project was funded by California State Parks Off Highway Vehicle Program, California Department of Fish and Wildlife Watershed Restoration Grants Program under Proposition 1 and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.

This blog was written by Sinjin Eberle & Page Buono

The Center for Colorado River Studies at Utah State University recently published a preprint edition of their new white paper titled, “Alternative Management Paradigms for the Future of the Colorado and Green Rivers.” The authors of the paper include Kevin Wheeler, Jack Schmidt, Brad Udall, and former Colorado River District General Manager, Eric Kuhn, among a few notable others in the climate modeling and Colorado River management space (Disclosure: Jack Schmidt and Eric Kuhn both serve voluntarily on American Rivers’ Science and Technical Advisory Committee.) The new publication builds upon a 2020 white paper, “Strategies for Managing the Colorado River in an Uncertain Future.” Wheeler et. al ran scenarios for various planning strategies on one of the most managed rivers in the world, the Colorado, to better understand the implications of those decisions in a hotter and drier future. Using the same computer modeling tools used by basin managers (the Bureau of Reclamation CRSS model), they integrated new climate and river flow data and looked out decades into the future to explore and predict water supply conditions under various scenarios.

The outcome of the study, in short: we’ve got to be more creative, and we need to have some hard conversations about what kind of future we want for the Colorado River and all who depend upon it. American Rivers has been engaged with the authors of the study, and we’re coming up to speed with its prescient findings. But even more important than that, our desire is to spark a conversation with you about what kind of future lies before us, what this new science tell us about various realities on the river, and how can we design solutions for the river, together.

John Fleck, author of a pair of recent books on western water, recently posted his take on the study, including some of the key highlights. He underscored that “Under a relatively optimistic scenario (things don’t get any drier than they’ve been in the first two decades of the 21st century), stabilizing the system would require:

- The Upper Basin to not increase its uses beyond its current ~4-million-acre feet per year of water use.

- The Lower Basin to adjust to routinely only getting ~6-million-acre feet of water.”

Basically, that means adapting to living in a 10-12 million-acre-foot (MAF) river, rather than a 17 MAF river as the Colorado River Compact assumes. Obviously, this stuck out to us too. While the Law of the River (the Colorado River Compact) essentially promised 7.5 MAF for the Upper Basin and 8.5 MAF for the Lower Basin (then added in Mexico’s allocation later), the Alternative Management Paradigms study makes clear that this is now an unattainable, and unwise, ambition.

Fleck points out that “Upper Basin water users have averaged about 4-million-acre feet/year since the 1980’s, but with plans to use more. The Lower Basin has reduced their use from the allowable 7.5 MAF to 6.9 MAF on average over the last five years. So to balance things out, Upper Basin use can’t grow, and Lower Basin use needs to shrink. More than it already has.”

The authors write that “the primary purpose of this White Paper is to provide provocative new ideas,” and they warn that “the current management approach that allows only incremental changes to the Law of the River may be insufficient to adapt to the future conditions of the basin.”

With both the warning and the desire for new ideas and thoughtful conversation in mind, we wanted to share some of the top conclusions from the study as an invitation for further conversation:

- The Colorado River has been profoundly altered from its highest reaches to its delta. In the highly constructed and managed basin—complete with numerous transbasin diversions and large dams—the native river ecosystem has been profoundly altered, the Upper Basin less so than the Lower, but still to significant degree.

- Unrealistic future depletion projections for the Upper Basin confound planning. There simply isn’t enough water to meet the aspirations for growth of the Upper Basin. “Unreasonable and unjustified estimations create the impression that compact delivery violations…are inevitable. Such distortions mislead the public about the magnitude of the impending water supply crisis and make identifying solutions to an already difficult problem even harder.”

- Climate change is causing flow declines and additional declines are likely to occur. 2000-2018 flows in the Colorado River are nearly 20% less than during the 20th century. Even accounting for this decline is not sufficient for future planning—increased temperatures and the resulting aridity will likely precipitate further decline.

- The Colorado River exists in a tenuous balance between supplies, demands and storage. Unplanned changes in this balance are likely to lead to highly undesirable outcomes. The Colorado River is already stretched. Any actions that decrease the inflows or increase demand are untenable. “If the Millennium Drought conditions continue and the 2007 UCRC future depletion projections materialize, the Colorado River’s water supply cannot be sustainably managed.”

- Likely lower inflows and/or any increases to Upper Basin consumptive uses will result in a difficult basin-wide reckoning. Future reductions in water supply are likely, due to the effects of climate change, exacerbating tensions between the Upper and Lower Basin, especially if the Upper Basin increases its demand. Negotiations are already massively difficult. Planning for a supply that science suggests will not be realized makes difficult processes profoundly more difficult.

In addition to those “difficult reckonings” it is clear that unless something is done, the environment—the river itself—has the most to lose. But in addition to those, the study outlined these additional takeaways that are key to understanding the expansive challenge facing the Colorado River:

- Lower Basin shortage triggers based on combined Lakes Powell and Mead storage are more logical and clearer than existing triggers (and different from simply looking at the individual lake levels on their own)

- Neither a Fill Mead First nor Fill Powell First scheme promotes or improves Lower Basin water security

- Flaming Gorge Reservoir releases provide little Upper and Lower Basin Risk Protection

- Humans have significant control over demands but little control over inflows

- Dire situations require solutions far from historic norms

As Kuhn, Fleck and others have stated for years, the study demands a reimagining of what we want versus what we need when it comes to water, and it grounds us in future-looking predictions of what we’re likely to have, which isn’t more and will likely be less. This is, perhaps, the epitome of inconvenient science, but it’s important science nonetheless, and if history has taught us anything, it is science that we can’t ignore. Doing so will cost us greatly.

You can read the study HERE, and you can learn more by staying engaged with us as we continue the work of distilling and contextualizing this research through additional blog posts, and other outreach, in the near future. We hope to catalyze a dialogue here—dare we say, a movement—and we look forward to your reactions, comments and ideas.

In late 2019, U.S. Senator Ron Wyden from Oregon issued an unprecedented request of Oregonians to tell him which rivers across the state we should protect as Wild and Scenic. He asked us to essentially to vote for the rivers and streams with the cleanest water or most outstanding recreation, or fish and wildlife habitat.

We at American Rivers were preparing to get out the vote. We had well-laid plans to barnstorm the state along with our partners collecting data on rivers, hosting public events and forums to hear from Oregonians rural and urban about their favorite streams and why. When the COVId-19 pandemic hit, and data collection and public forums were replaced by justifiable lockdowns and lifesaving stay at home orders. But we still had to chronicle the incredible richness of Oregon’s free-flowing streams and meet Senator Wyden’s call to action.

With in-person school, then camps and play dates cancelled for my kids my ability to travel to chronicle these streams without my family was not an option. We needed to get creative, so we came up with the idea of doing 7 “River Camps” around the state. One early summer evening my 4-year-old son and 8-year-old daughter sat around the dining room table and drew circles around rivers a map of the state of Oregon. Some of the trips would be within an hour of our house and some involved 7-hour drives and in-depth 9-day camping trips within a stone’s throw from the California or Nevada borders.

Throughout our trips (so far, we’ve seen 5 of the 7 wonders) we did research on the river dependent native species, the importance of salmon, the shade of old-growth trees, and the indigenous tribes that have called these watersheds home since time immemorial. We saw all kinds of wildlife—birds, bears, deer, and even a cougar swimming across the Rogue River. We even caught an ocean-bright salmon—a miracle that nourished us for days.

We saw with our own eyes the evidence of why the small streams are so important. My kids snorkeled in these streams seeing baby salmon, steelhead, and cutthroat trout when the larger rivers were so warm that they would be lethal to the same fish. Wading in their waters you could feel the dramatic difference in temperature between ankle-shocking cold small streams and the warmth of the big rivers they flowed into.

Our first trip was to Thirtymile Creek, a tributary creek of the lower John Day Wild and Scenic River located in north-central Oregon. At 281 miles, the John Day is the longest free-flowing river in the contiguous United States and Thirtymile Creek is an essential summer steelhead stronghold. To get to this rugged and remote high desert area isn’t easy but it is worth it for the expansive canyon scenery, solitude and fish and wildlife habitat. As we dropped into the steep canyon hundreds of birds could be heard as we neared the creek. In years past, we’ve seen an abundance of deer that use the Thirtymile canyon for forage and cover.

Miles of Thirtymile Creek were acquired by the Bureau of Land Management several years ago to establish a new public access point to launch multi-day river trips from the Rattray family. Rita Rattray, who still runs shuttles for boaters, was born on the ranch near the banks of the John Day River which she said still looks like it did back then early in the 20th Century. The first time I met Rita and her husband who once outfitted guided hunting and fishing trips on the John Day, he summed up the importance of Thirtymile Creek. He said, “You can run up and down the length of the John Day River to find fish, but there is no need, this is to best 100-yards of fishing on the whole damn river,” pointing the mouth of the creek. According to the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife fish biologists that were doing surveys of the creek that same year Thirtymile Creek is a stronghold for the summer steelhead, providing essential habitat.

Our second “River Camp” was on the Little Deschutes River, which flows over 100 miles south to north out of the Mount Thielsen Wilderness in the southern Cascade mountains. The Little Deschutes River is home to Redband rainbow and brown trout, resident and migratory birds, and provides essential habitat for the Oregon Spotted Frog which was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Additional protections for the river will help protect this fish and wildlife and recreation.

My wife’s family which has been in Oregon for five generations has owned property, a tree farm, on the Little Deschutes for over 50 years that abuts BLM land and serves as a destination each year for the extended family to camp each 4th of July. The property is named “WUG” after the last names of the three siblings who originally agreed to purchase it over five decades ago. The river has literally connected this family and its friends for generations through family gatherings, weddings, surprise birthdays.

I once met a rancher and head of a central irrigation district in nearby Prineville who was a part of a contentious settlement agreement American Rivers had negotiated. I happened to mention my wife’s family property. “You mean WUG?,” he said. “I grew up swimming there in the summer.” He ended up inviting me to come see his ranch sometime. Every year, this beautiful little river helps knit together the social fabric of our family and maybe the community.

Our third “River Camp” was close to home, only about an hour West of Portland, on the Little North Fork Wilson River that flows into its larger and better-known cousin the Wilson River near the Oregon coast. On this hot September day, the Wilson was low and warm so we could wade across easily from where we parked on a gravel bar. In the rain-swollen winter this gravel bar would have been underwater. We hiked up the Little North Fork and saw a lush river corridor full of birds and walked in the cold water of the river seeing baby salmon and a cutthroat trout of about 12 inches. I was told by fish and wildlife biologists that the Little North Fork is a haven for all kinds of species including birds, deer and elk, salmon and amphibians. After a couple hours of hiking and swimming in the creek we headed back to the car where we found the gravel bar now full of people swimming and barbequing, using this river as a beautiful and no-cost place to spend a summer Sunday afternoon. While they were not there to chronicle the native species that these rivers support, it was a great reminder of the value of a river as a place just to relax with family.

Throughout our travels I learned two major lessons—one ecological and one sociological. First, I came to learn just how important the lesser-known tributary streams are to the larger well know rivers and why they deserved protection. Tributary rivers and streams—Indigo, Silver and Lawson Creeks, the Little North Fork of the Wilson River and Lookingglass Creek to name just a few provide the ecological life support system for the larger, better known rivers such as the Rogue, Illinois, Wilson, and Grande Ronde Rivers. These are the beating heart of our public lands in Oregon. I saw evidence of their importance this on during our travels and will highlight them more in the weeks to come.

Second, I learned the importance of these rivers and streams not just for fish and wildlife, but to the people who rely on them for a free place to swim, camp or fish, a place to sustainably make a living, or for their drinking water. The communities where these streams flow such as Brookings, Tillamook, Post or La Pine rely on these streams for all of the outstanding values that they provide.

Seeing all of this through the eyes of my kids of course has left an indelible mark on me. Hopefully a little has rubbed off on them. By the end of our “River Camps” it became as clear as the water in the rivers and streams we explored that these are the special places where the earth is already proving resilient in the face of climate change. These are the waters that are worth fighting for, and we have Senator Wyden to thank for leading the charge.

Note: David will be chronicling some of the other rivers and streams he’s been exploring under consideration for protection as Wild and Scenic in Oregon.

American Rivers sees the first one hundred days of the new Biden Administration as an opportunity for real change in protecting our Nation’s waters and water resources. In our 2021 Blueprint for Action , we identify overturning or reversing the anti-water protection regulations and actions of the past four years as a top priority for our engagement with the Biden Administration.

On President Biden’s first day in office, he issued numerous executive orders impacting the regulatory rollbacks enacted by the last Administration that weakened critical environmental protections. President Biden’s Executive Order on Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis ordered federal agencies to review the regulatory actions from the past four years. These reviews cover most of the Federal agencies and are listed in detail in the Executive Order. These reviews include myriad issues under the jurisdiction of the EPA, including water, air, and toxics—many provisions important to American Rivers priorities. Reversing, replacing, or rescinding these rules is critically important to protecting the Nation’s water resources and enabling American Rivers to pursue its work. We view these early Executive Order actions by the Administration as a tremendous first step toward success for American Rivers priorities.

There are several key water rules and actions that we opposed over the last four years included in the Biden ordered reviews. Undoing these actions are critical to American Rivers’ work. These include:

- Navigable Waters Protection Rule;

- Nationwide wetland permits;

- Lead and Copper Rule;

- Coal Ash Rule;

- NPDES Electronic Reporting Rule;

- Steam Electric ELGs;

- Perchlorate decision;

- Section 401 State Certification of Water Quality Rule;

- Maryland’s Phase III Watershed Implementation Plan;

- Proposal to increase Shasta Dam capacity.

President Biden also directly rescinded several previous Executive Orders for actions that American Rivers had previously opposed. Trump’s Executive Order 13778 was repealed. This order directed EPA to begin repealing the Obama era Waters of the United States (WOTUS) rule. Biden’s action now indicates to EPA to examine the Trump era Navigable Waters Protection Rule for replacement. Executive Order 13868 was also repealed. This order resulted in the new rule governing Clean Water Act (CWA) Section 401 requirements. This action also indicates Biden wants EPA to review the Section 401 guidance, and the Section 401 Certification Rule issued last year. The issuance of these two regulations caused American Rivers to join with partner environmental groups in legal action to overturn these environmentally harmful rules.

These opportunities to reverse the last Administration’s harmful regulations are exciting developments. Once the changes are complete, it will enhance critical protections of our Nation’s rivers, streams, and critical water resources. With these tremendous environmentally protective changes, American Rivers will now pursue more progressive policies that will continue the advancement of our mission to protect wild rivers, restore damaged rivers and conserve clean water for people and nature.

By 2050, most people on Earth will live downstream of tens of thousands of large dams built in the 20th century, many of them already operating at or beyond their design life, according to a UN University analysis.

The report, “Aging water infrastructure: An emerging global risk,” by UNU’s Institute for Water, Environment and Health, provides an overview of dam aging by world region and details the increasing risk of older dams. According to the report, most of the 58,700 large dams worldwide were constructed between 1930 and 1970 with a design life of 50 to 100 years, adding that at 50 years a large concrete dam “would most probably begin to express signs of aging”.

Aging, unsafe dams are a growing threat in the U.S. From the failure of the Edenville Dam in Michigan in May 2020, to the failure of multiple dams in the Carolinas, this is an issue that continues to put lives and property at risk.

The Biden-Harris administration can begin to address this challenge by investing in dam safety and dam removal. In our 2021 blueprint, American Rivers calls on the administration to launch a national fund to prioritize and fund dam removals.

This includes:

- Fund barrier removal to improve habitat, connectivity, water quality and public safety

- Develop a schedule for reviewing the operation of federal facilities

- Develop accurate budget projections that reflect the true costs of maintaining and operating federal water infrastructure.

- Facilitate dam removal and river restoration through the hydropower relicensing process.

“From Michigan to the Carolinas, we’ve had multiple wake up calls that too many dams are outdated and unsafe. This report raises another alarm that we must not ignore,” said Brian Graber, senior director of river restoration for American Rivers.

“The U.S. has been a leader in dam removal and river restoration. We must continue to lead by investing more in dam safety and river restoration to keep our rivers healthy and our communities safe.”

Most things found at cleanups are cigarette buds, plastic bottles and cans. Sometimes it’s a few tires, couches and shopping carts. Then there are things you would (to put it lightly) not expect.

Here are some of those interesting cleanup finds:

A $100 bill

Yes, you heard that correct. A volunteer during a Friends of Poquessing Creek cleanup found a $100 bill during a cleanup outside of Philadelphia and rather than keep it for themselves, they donated it to the group organizing the cleanup. Although cash is not that unusual to find, a $100 bill is. If this isn’t more of a reason to participate in cleanups, we don’t know what is.

Watershed Council

Halloween costumes and decor

Why are these items being found during April cleanups? We have no idea, but it happens more than you think. If you are planning outside Halloween décor or taking a walk in your costume, please make sure your items are secured. Or else, you may cause a fright at a future cleanup.

Swamp monster Elmo

Imagine this: While canoeing with your child, you start picking up litter, but you both get the feeling that something is watching you. You shrug it off and get back to cleaning. Then, just as you turn your head, you see something… Is it a rock? Is that a face? What is that thing? – False alarm. It’s only a floating, mud-covered Elmo in need of rescue.

A punching bag

Don’t worry, we’re just as confused as you.

Vacuum cleaners

The Mayor’s Grand River Cleanup hosted by West Michigan Environmental Action and sponsored by Cascade Blonde American Whiskey, volunteers found not one, but TWO vacuum cleaners during their annual fall cleanup.

Clean rivers mean clean drinking water and clean drinking water is good for people, wildlife and communities. It’s also vital making great whiskey! Without clean water, great whiskey isn’t possible. That’s why Cascade Blonde is committed to helping to protect and restore our nations rivers.

Have you come across an interesting item during a cleanup? Share the photo(s) with us and Cascade Blonde American Whiskey, sponsor of National River Cleanup® on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. Tag @americanrivers and @cascadeblonde.

The convergence of a multi-decadal, climate-fueled drought, a trillion-dollar river-dependent economy, and a region with growth aspirations that rival any place in the country has peaked speculative interest in owning and profiting from Colorado River water. An “open market,” as described by investors in the recent New York Times article, Wall Street Eyes Billions in the Colorado’s Water, while extremely unlikely, would present a grave danger to rural communities, farms and ranches, clean, safe, reliable drinking water for people, and ultimately the health and sustainability of the Colorado River ecosystem itself.

Water speculation is not a new concept in the West. Unfortunately, the article gives short shrift to the role of states in managing surface water in the public interest. In all Colorado River Basin states, the surface water is held by the state and water rights are issued for certain specified beneficial uses. These rights cannot be changed to other uses without thorough regulatory review by the state to ensure no “injury” to other water rights holders (like a neighboring ranch or the next town over) and to ensure that public interest is protected. Tribal rights in the Colorado River Basin also come with a number of court-ordered or legislative restrictions on how water may be transferred.

Additionally, there is absolutely no logic to the idea that states would agree to let a private investor have its own “account” in Lake Powell, just so it could “sell” that water back to the Upper Basin states.

Water in Colorado and throughout the West is tied to the land and must, by law, be put to a specific use like agriculture, energy, or municipal drinking water. Water cannot be bought and held without putting it to “beneficial use,” which means that in order to profit from held water rights, these investors would have to move the water. In all likelihood, it would move away from a farmer’s field to a city – in many cases, never to return. So, while water speculation isn’t a new concept or threat, framing investments in land in order to secure water rights as “beneficial to the environment” is a new tactic. But the end remains the same: profit for few investors at the expense of human and wildlife communities, and the river, will be the only actual benefit.

Unfortunately, the article falsely implies that Demand Management follows the export model for water, which is not the case. Instead, the guiding concept behind demand management is to NOT move water from farms to cities to facilitate municipal growth. Instead, Demand Management aims to reduce water supply risk for all water users in the face diminishing water availability by temporarily and voluntarily reducing water use. If designed and implemented appropriately, Demand Management can generate environmental and recreational flow benefits, while keeping water local and in the local watershed or even the broader Colorado River basin. The purpose of Demand Management is to sustain productive agriculture, not permanently dry it up.

For these reasons, American Rivers is partnering with The Nature Conservancy, Trout Unlimited, several ranching families, and the State of Colorado to test, model, and better understand the consequences and benefits of Demand Management and to design a program that can be implemented at scale to reduce risk, preserve agriculture, and benefit the environment. It is critical to understand that the farmers and ranchers involved in these programs are leading efforts to keep water with the land and preserve Colorado’s agricultural heritage for future generations in the face of an increasingly water scarce reality.

Not all investments of capital wealth in water are designed strictly for profit. There are a number of innovative private companies that are dedicated to helping solve some of the West’s most pressing environmental challenges by leveraging private capital. In Southwest Colorado, Quantified Ventures’ is working with local stakeholders on a Wildfire Mitigation Environmental Impact Fund. Like much of the west, Southwest Colorado is facing an increased threat of wildfires from past fire suppression policies, drought conditions and beetle-infested forests. This Wildfire Mitigation Environmental Impact Fund will utilize capital from private investors as well as revenues from biomass generated from forest thinning to offset the financial burden that any entity covers for wildfire mitigation in wildland-urban interface of the San Juan National Forest. The project fosters regional collaboration through shared financing and project implementation, while creating the opportunity to scale up wildfire mitigation by creating a revolving loan fund that reinvests proceeds into future projects. Because of the revolving loan, the impact of the fund will grow over time as capital is re-deployed for forest health treatments in new areas beyond this initial plan.

There is some promise in approaches that deliver private capital investments to benefit the restoration and protection of rivers and streams. These investments can expand or enable projects that are eventually funded by public agencies, NGOs and local landowners. However, we fear that the private equity firms looking to the Colorado Basin and the water it provides as a commodity are really only interested in one thing—profit.

When we first saw this photo, many of us asked the question, “what is that?” or “where can I get one for my river?”

It all started three years ago when Westchester Parks Foundation (WPF) created the “Clean River Project” with a school group in White Plains, NY. The project’s purpose is to address floatable trash, a major water quality issue, on the Bronx River.

To do this, WPF installed two booms about 7 miles apart, that float across the Bronx River from bank to bank and supported by cement polls. The booms are comprised of connected floatation devices with a lip that sits half in/half out of the water. Basically, it catches trash floating down the river. After floating for a week or two, the booms end up looking like this (see picture below).

River | Photo by Erin Cordiner and Westchester Parks Foundation

Also featured in the photo are volunteers removing floatable trash caught by a boom. This photo was captured at an event hosted by WPF and Riverkeepers and resulted in around 40 volunteers collecting 5,244 items from the river—equaling 288 pounds of trash. These volunteers together put in a total of 156 hours of work for this cleanup event!

Every other week WPF volunteers arrive on site, slide on their waders and hop into the river to remove the collected trash one by one. This activity happens quite regularly to make sure the booms, and river are kept clean.

As they remove the trash, volunteers count bottles, cans, straws, and more. One volunteer is tasked with recording every piece of trash pulled out. This allows WPF to track the number of pieces of trash and the type of trash. Erin Cordiner, WPF’s Director of Volunteer Programs says, “the information we collect helps find the sources and stops trash from entering the river in the first place.”

According to WPF, the three most common things found are Styrofoam, cigarette butts and plastics. Sometime this year the high school volunteers will be analyzing the compiled data of their research to propose different strategies to help prevent more river pollution.

To address these issues, WPF engages volunteers by promoting outreach to local businesses whose products end up in and along the river, creating a uniting message surrounding the harm to our waterways caused by non-biodegradable materials.

WPF engages the public to advocate for and invest in the preservation, conservation, use, and enjoyment of the 18,000 acres of parks, trails, and open spaces within the Westchester County Parks system. Their 2019 National River Cleanup® winning photo is only a glimpse into the astounding work that they do every day. During the peak season of April-November, WPF engages with their community with all kinds of events every single day!

It’s all about community engagement… and clean parks of course! WPF notes, “Events like these bring together their community, at all ages, and shows them exactly what happens to their trash if it is not disposed of properly. It is a chance for people to really see how trash can wind up in their local parks that they might not otherwise notice. Once you get a few people involved with a local project, it doesn’t take long before you are able to inform an entire locality about positive change that is possible through simple acts of volunteering!” They have since been able to expand to two locations with four school groups. They are always looking for more local groups, school groups or otherwise, to get involved with their Clean River Project so reach out to them if you’re interested!

If you are an organizer and looking for a new way to clean up and catalog the trash in your river while engaging community members, this may be the project for you. The booms need to be checked regularly to collect the trash. If anyone is looking to do a similar project, WPF invites you to reach out to them. They are willing to offer advice, logistics and more to help you get started.

Congratulations to WPF, winners of the 2019 National River Cleanup® Photo Contest. Thank you for all your hard work keeping our rivers clean!

As President-elect Biden’s Cabinet appointments take shape, one thing is clear: addressing climate change and environmental justice will be at the forefront of his administration. That’s a good thing for the planet and for rivers and clean water.

In historic choices, Biden named Rep. Deb Haaland to be Secretary of the Interior and Michael Regan to be Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Haaland, a citizen of Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, will be the first Native American Cabinet secretary. Regan, who has led North’s Carolina’s Department of Environmental Quality, will be the first Black man to run the EPA.

Also joining the Cabinet will be former Michigan Governor Jennifer Granholm as Secretary of Energy. Former Iowa Governor Tom Vilsack will be returning to serve as Secretary of Agriculture, a position he held for eight years under President Obama.

In addition, Biden named former EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy to head a new White House Office of Climate Policy, where she will lead the administration’s domestic climate change initiatives. Her counterpart on the international front will be former Secretary of State and Senator John Kerry, who will serve as a special envoy on climate change.

Leading the White House Council on Environmental Quality will be Brenda Mallory. She is an experienced environmental lawyer, working at EPA and CEQ and most recently at the Southern Environmental Law Center, a public interest environmental law firm that has represented American Rivers in litigation.

Each of these appointments reflects President-elect Biden’s commitment to make addressing the existential threat of climate change a top priority for his administration.

Perhaps no appointment better signals the importance of addressing climate change than Biden’s appointment of Brian Deese to lead the National Economic Council. In the Obama administration, Deese was a senior advisor to the President on climate and energy policy, where he helped negotiate the Paris climate agreement. President-elect Biden has pledged to reenter the Paris agreement on the first day of his administration.

With the appointment of Deese to lead on economic policy, Biden is making clear that addressing climate change and restoring the nation’s economic health go hand-in-hand.

At American Rivers, we recognize that the impacts of climate change often register first and hardest on rivers, with more frequent droughts and devastating floods. These impacts, in turn, fall disproportionately on Black, Latino, and indigenous communities. To address these problems, American Rivers developed our 2021 Blueprint for Action for healthy rivers and clean water. In addition, our comprehensive report, Rivers as Economic Engines: Investing in Clean Water, Communities and Our Future, provides a roadmap for the new administration and Congress on how investing in healthy rivers and clean water can help address climate change, further environmental justice, and rebuild our economy.

With the team President-elect Biden is putting in place, American Rivers should find a receptive audience for our policy recommendations, helping to repair the damage the Trump administration inflicted on rivers and clean water and forge a better, more equitable future of healthy rivers and clean water everywhere, for everyone.

American Rivers recently praised PacifiCorp and parent company Berkshire Hathaway for stepping up to ensure dam removal and river restoration on the Klamath River in Oregon and California. While we applaud PacifiCorp for taking responsibility for the damage that their dams have caused on the Klamath, they still have work to do on Washington’s Lewis River. American Rivers, the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, the Yakama Nation and other partners are working hard to hold them accountable.

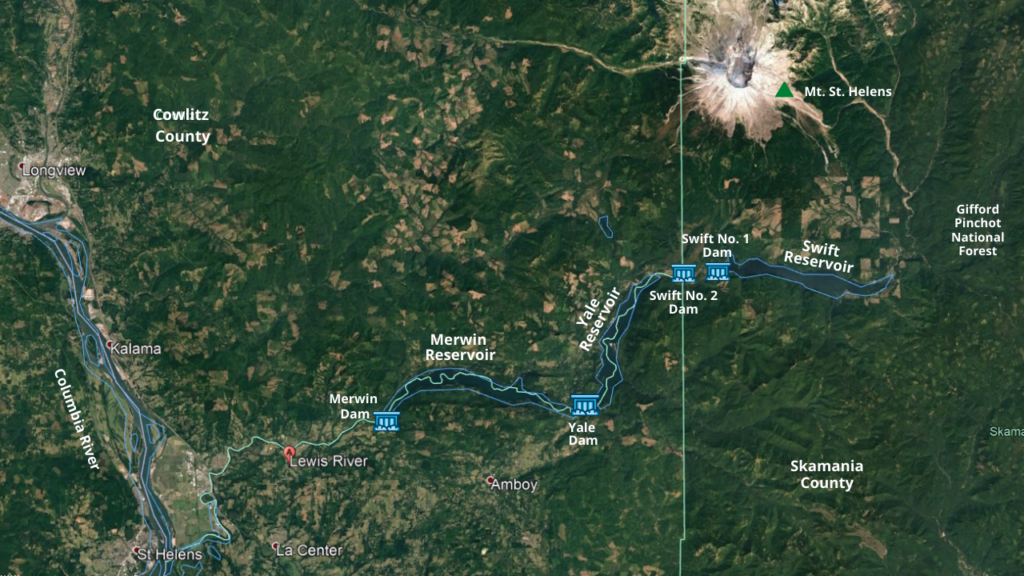

The Lewis River flows through southwest Washington beginning at Adams Glacier on Mt. Adams and drains a basin of roughly 1,400 square miles. The river winds its way through Gifford Pinchot National Forest before joining the Columbia River near La Center, WA.

The Cowlitz, Yakama, Klickitat, and Chinook people have all called the basin home since time immemorial and the river was home to abundant salmon, central to their life and culture. Today, four large hydropower facilities block the river, preventing salmon and bull trout from returning to their home waters. Constructed between 1931 and 1958, the Lewis River hydroelectric project consists of Merwin Dam, Yale Dam, and Swift No. 1 and Swift No. 2 which are joined by a canal. Cowlitz County Public Utility District owns the Swift No. 2 facility, while PacifiCorp owns Merwin, Yale, and Swift No. 1 and operates all four facilities to produce a total of 580 megawatts of hydroelectricity – enough power to supply approximately 460,000 homes per year. While some salmon not used for broodstocking at the Lewis River or Merwin hatcheries are trapped at the lowermost dam and transported above the uppermost dam by truck, these facilities deny access to traditional spawning habitat for a majority of adult Lower Columbia River salmon and prevent juvenile salmon from outmigrating to the ocean.

In 2004, the utilities signed a settlement agreement with American Rivers and other non-governmental organizations, eleven federal and state governmental agencies, the Cowlitz Indian Tribe and the Confederated Bands and Tribes of the Yakama Nation. This agreement accompanied the most recent license required to operate the dams, which was granted by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in 2008. The agreement stipulated that the utilities must provide fish passage facilities which would allow anadromous fish to move through each of the three project reservoirs by their own volition – opening up over 170 miles of spawning habitat. The requirement of full fish passage throughout the entire Lewis River was celebrated by salmon advocates throughout the region.

In 2016, the utilities presented information to the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in an attempt to evade their obligation to build fish passage facilities by claiming that habitat restoration actions can provide equivalent benefits to fish passage at a lower cost. Despite the significant scientific and technical information disputing this conclusion, NMFS and USFWS issued a determination that deemed fish passage “inappropriate” four years later. The federal agencies stated that PacifiCorp would likely not need to build two of the proposed facilities and could defer a decision to build the other two facilities until 2031 and 2035.

Emboldened by the decision made by NMFS and USFWS, the utilities have submitted amended applications to FERC that would allow them to renege on their agreement of building fish passage facilities throughout each of the three reservoirs. As stipulated in the 2004 Settlement Agreement, if fish passage is deemed inappropriate, the utilities will instead implement a habitat restoration plan. The utilities have proposed and filed applications for the “In Lieu plan,” a program which would seek to improve 41 miles of aquatic habitat in the headwaters of the Lewis River at the cost of $21 million — a savings of over $160 million from the original fish passage plan. Despite insufficient evidence provided by the utility companies or by NMFS to suggest that fish passage is inappropriate, the utilities are forging ahead with a cheaper plan that will fail to recover federally threatened Lower Columbia River salmon and bull trout populations.

NMFS requires that members of the Aquatic Coordination Committee (ACC), a committee formed under the 2004 Settlement Agreement to help coordinate and consult on aquatic measures related to the projects, to reach a consensus agreement before NMFS will consult on the proposed habitat restoration plans. Members of the ACC, which includes American Rivers staff, are now being asked to sign off on the utilities’ attempt at skirting their obligation to provide fish passage through the reservoirs. In addition to American Rivers, other parties to the ACC that have voted not to approve the In Lieu plan include the Lower Columbia Fish Recovery Board, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Cowlitz Tribe, and Trout Unlimited.

There has been insufficient evidence provided by the utility companies or by NMFS to suggest that fish passage is inappropriate, and to move forward with the In Lieu habitat restoration plan without the consensus of the Settlement Agreement parties is premature. The In Lieu plan put forth by the utilities does not present a comparison of habitat restoration impacts to impacts of full fish passage through the reservoirs. Generally, the In Lieu plan errs on the side of over-estimating the benefits of habitat restoration while under-estimating the benefits of full fish passage through the dams.

There remains too much uncertainty when it comes to how and when salmon and bull trout populations will respond to habitat restoration. American Rivers does not support the In Lieu plan put forth by the utilities and does not agree that the In Lieu plan will aid in Lower Columbia River salmon recovery.

Sixteen years ago, PacifiCorp and Cowlitz County PUD made a promise to address the damage that their dams inflict on the Lewis River by installing fish passage. Now, they are trying to get out of this obligation. They have a responsibility to restore the Lewis River’s salmon runs and that means ensuring fish passage at the dams. For the river, the salmon, and all who benefit from a healthy Lewis River, we won’t settle for less.