A crisp 12-page ruling has brought to a close a lawsuit that began back in 2013, in which the state of Florida asked the U.S. Supreme Court to consider an “equitable apportionment” of waters shared with the Georgia in the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) River Basin.

The Court has found that “Florida has not met the exacting standard necessary” to warrant a Court decision in its favor against the interests of another state.

Essentially, the Court found that Florida failed to prove that Georgia’s water consumption caused the collapse of the oyster fishery in Apalachicola Bay. The decision makes a point to note that Florida did not sue the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which plays a major role in managing river flows in the ACF basin. And it cites the report of the first Special Master appointed to hear this case, who found that the solution Florida proposed with its suit – a cap on Georgia’s water consumption – might not even work without the Corps of Engineers being at the table.

The Court’s opinion acknowledges the collapse of the bay fishery, and it acknowledges the complexity of the environmental factors that determine the bay’s health. But what have long been seen as flaws in Florida’s legal strategy in this case have now produced a unanimous decision against Florida.

This decision does not give anyone a free pass to disregard the health of the Apalachicola River and Bay. The Court noted: “We emphasize that Georgia has an obligation to make reasonable use of Basin waters in order to help conserve that increasingly scarce resource.”

Indeed, Georgia must continue to improve its stewardship of the basin’s rivers, with or without legal pressure from Florida. We and our conservation partners will continue to help the State of Georgia ensure that it does that! And, critically important, the Corps should heed the call of environmental groups and improve its management of water in the basin to support the environment.

It’s a shame that communities around Apalachicola Bay have had to suffer the very real consequences of a degraded and damaged ecosystem. And this ruling closes off one legal pathway to fixing these problems. But as this door closes, other doorways to real solutions for the basin might open.

The good news is that stakeholders throughout the basin can now move forward toward solutions that will benefit the environment and communities throughout the entire basin, upstream and down. We at American Rivers support the ACF Stakeholders effort and the group’s Sustainable Water Management Plan for the basin.

If a river system is not healthy at its downstream end—particularly, if it cannot support a healthy estuary—then there are problems upstream that need attention. As climate change poses increasing threats to rivers and communities throughout the region, American Rivers and our partners look forward to continuing efforts in a collaborative spirit to ensure the health of rivers throughout the entirety of this vital river basin.

2020 was a tough year. What takeaways will you bring to this new role?

Because of the pandemic, we’ve all been stressed and anxious. But nonetheless, it’s quite impressive what the river movement accomplished last year: 69 dams removed and some major protections advanced for rivers in Montana, Oregon and elsewhere. We proved that rivers really do connect us — especially in the face of so many crises.

I think we’ve also been reminded that connecting to the outdoors, to rivers and to the peace of nature can give us and our families the emotional level setting that is especially important this year.

While our country has been facing the pandemic, climate change, environmental injustice, and an economic crisis, we’re also seeing how investing in healthy rivers can be part of the solutions to these interconnected challenges. We’ve seen how rivers can bring people together, and how protecting clean water and rivers strengthens communities. American Rivers is poised to keep building on its reputation for doing that.

Why should river lovers be optimistic?

We are facing several crises in this country. We see public health, economic, racial and climate challenges every day. Yet, moments of stress and challenge also present new opportunities to be creative and find a way to solve big problems. I joined American Rivers because I believe that we have unprecedented opportunities, right now, to bring ecosystems back from the brink of disaster and to fundamentally change the way humans manage water scarcity and floods.

American Rivers will keep removing dams and restoring rivers. We will keep working toward a future of clean water for everyone. The work that we do can absolutely help address and resolve the crises we are facing.

Rivers are great teachers. They teach us about persistence, that a little trickle of water can carve a massive canyon. Little by little, we can make a huge difference. During my career in conservation, I have seen this work, alongside our members, supporters and allies, have an enormous, positive impact — just like that trickle of water.

After 30 years of working for positive environmental change, what keeps you going?

I’ve worked in conservation, but I’ve also been in the private sector. I’ve worked with industries, I’ve worked with government. I’m inherently an optimist. I’ve learned there are so very many well-intended, great people. We just need to work with everyone because at the end of the day people do want clean water. People do love rivers. American Rivers is the leading organization for bringing people together around protecting and enhancing something that we all have in common. And that basic human connection is incredibly hopeful.

Why does your life need rivers?

My sense of self is defined by rivers. I grew up in a small family with just my mother and older brother. Across the street from our home was a small creek that led directly into the Potomac River. So, my brother and I spent countless hours in that creek, in the surrounding woods and wandering along the shores of the Potomac. It was in that creek and on that river that I both physically and emotionally grew up.

We need it physically to drink. Wildlife needs it as habitat. But emotionally, psychologically, deep in our souls, there is magic in moving water because it connects us to greater forces than ourselves, it connects us to the natural world, and it connects us community to community. Water can also take us on a journey. This is part of the role of American Rivers — to be the voice for why we need rivers.

What’s your favorite river?

I have to start with the Potomac. I know each wave at each water level. It’s the river that gave me a love of rivers. I was a rafting guide through the Wild and Scenic stretches of the Chattooga River in Georgia. You can be on this protected river — not that far from Atlanta — and feel emotionally so far away.

I love the Chattahoochee in the Southeast, as well. The Killik River in Alaska that flows north out of Gates of the Arctic. I was on a trip up there once and we were seeing muskox and grizzly bears. That’s a river that’s way the heck and gone.

I’m so proud that American Rivers works on that full spectrum — from an urban river that needs serious restoration to something so pristine and untouched. We work on rivers of all sizes and in all locations, with all different needs, to protect and restore the magic rivers hold. That’s a pretty important and exciting mission.

When President Biden took office earlier this year, American Rivers prepared a bold blueprint for action that calls on the administration to investment in rivers and clean water. Priorities in the next year include reversing rollbacks that hurt ecosystems and communities, improving how we manage floodplains, and investing in a national dam removal initiative. One of our most important calls to action — and the one that’s closest to my heart — is to protect exponentially more rivers under the landmark Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

Wild and Scenic designations safeguard rivers against future activities — like mining, development, or dams — that could do harm to the many benefits a river provides, like clean water and wildlife habitat. Further, because they require stakeholder input, they bring communities together around shared concern and care for local rivers and streams.

Right now, bills to protect over 6,700 miles of proposed Wild and Scenic Rivers and streams are making their way through the Congressional approval process. That includes the River Democracy Act, which would designate over 4,600 river miles in Oregon in one fell swoop; legislation that would nearly double the number of river miles protected in Montana, and a long-awaited bill to safeguard streams on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula.

Given that the total miles of protected rivers nationwide is just under 13,000, these new protections represent a 50 percent increase in the entire Wild and Scenic Rivers System. That’s pretty impressive.

Wild and Scenic designations don’t happen on a dime. They’re usually the hard-won result of people—everyone from passionate river lovers and business leaders to conversation groups and tribes— working together to make them happen. Most often, they’re the product of decades of trust building, stakeholder input and collaborative development.

While it feels like something is in the air for Wild and Scenic Rivers these days — or maybe in the water — current efforts are riding on decades of work. The Gila River in New Mexico, for example, was first proposed for addition to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System by Congressmen Manuel Lujan Jr., a Republican, and Harold Runnels, a Democrat, way back in 1974. The Gila is today once again proposed for protection.

So Wild and Scenic Rivers are having a moment. And, while that moment is overdue, it’s also right on time. Rivers in America remain vulnerable to damming, mining, oil and gas development, and other development pressures. Protections for our last, best rivers — these critical suppliers of clean water, vital habitat, reprieve and sanity — should be a top priority of the Biden administration. And, there’s a lot the administration can do. For starters, it should:

- 1. Issue an Executive Order calling for protection of rivers and riverside lands by doubling the size of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System as a part of protecting 30 percent of Earth’s natural areas by 2030 (30 x 30) — and as a climate resilience strategy. Early progress can be made toward this goal by actively supporting the pending Wild and Scenic River bills in Congress.

- 2. Issue an Executive Order that directs each federal agency, as part of its normal planning and environmental-review processes, to emphasize the importance of identifying rivers with Wild and Scenic potential and to avoid or mitigate adverse effects on rivers identified as eligible for Wild and Scenic River designation under land-management plans or the Nationwide Rivers Inventory, until Congress has acted on their consideration.

- 3. Dedicate additional funding and personnel resources to the protection and management of Wild and Scenic Rivers.

We’re ready to work with the Biden administration on these and other important ways to protect and preserve the rivers that are so very key to the history, and future, of our country.

If Congress passes and President Biden signs every piece of current introduced legislation to protect rivers, approximately 6,700 new miles of rivers would be permanently off limits to future mining, development and dams. But that’s just a number.

One of the wonderful things about Wild and Scenic Rivers is how unique every individual designation is, and how often the process and structure of the protection reflects the unique character of the community that pursues protection for their river. With that individual flavor in mind, I wanted to share some stories about some of the exciting proposals making their way through Congress right now.

OREGON: Senators Wyden (D-OR) and Merkley (D-OR) announced the River Democracy Act in January after an unprecedented public process in which Oregonians recommended rivers on public land, such as our National Forests, that they wanted to see protected. The result is the introduction of legislation to protect Oregon’s greatest natural wonders — its rivers — to conserve clean drinking water, fish and wildlife habitat, and outstanding recreation that supports sustainable economic development across the state.

With over 2.5 million Oregonians getting their drinking water from Oregon’s public lands, according to the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, it is not surprising that drinking water providers are strongly supporting Wyden and Merkley’s bill, which seeks to protect over 4,600 miles of rivers and streams in the McKenzie, the Deschutes, the Grande Ronde, the Rogue, Illinois and Nestucca river watersheds and elsewhere.

NEW MEXICO: The M.H. Dutch Salmon Greater Gila Wild and Scenic Rivers Act would protect nearly 450 miles of the Gila and San Francisco rivers and their tributaries. Silver City, New Mexico, an incredibly vibrant community and the gateway to the Gila, is the seat of a county that is heavily dependent on mining, as well as the recreational, emotional and cultural benefits of the outdoors. The support for protecting the Gila is strong — even among the pro-mining residents and politicians, who want to see the benefits of a Wild and Scenic designation for the Gila to help the community diversify the county’s economy.

I have witnessed firsthand, on the river and in public meetings about protecting the Gila, some of the most deeply personal stories from business owners and mayors about the value of the river to their community and their families. One mayor said something to the effect of, “We don’t need to go to Disneyland, we have the Gila.” This is where residents of Grant County have spent generations fishing, camping, or just sitting with friends, parents and kids. And the Gila river watershed provides lifetimes of memories for free.

MONTANA: The Montana Headwater’s Legacy Act would protect nearly 336 miles of rivers — nearly doubling the protection of the best, free-flowing rivers in a state that’s truly defined by rivers. Sections of the Madison, Gallatin, Yellowstone, Smith, Boulder, Rock Creek, and the Beartrap Canyon of the Madison are all included in the bill.

This campaign was born more than a decade ago out of a truly grassroots effort that has included an incredible amount of public outreach asking Montanans what they wanted to protect and why. This approach was groundbreaking and painstaking, including hundreds of meetings fully open to the public, some even advertised on local radio stations. The results speak for themselves, with over 3,000 Montanans and more than 1,000 Montana businesses voicing their support for significant new Wild and Scenic River designations.

WASHINGTON: In mid-February, Washington Senators Patty Murray and Derek Kilmer, both Democrats, announced they would reintroduce the Olympics Wilderness and Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which would protect 464 river miles and more than 126,500 acres flowing out of Olympic National Park and the surrounding National Forest. The Elwha, the Hoh, the Queets, the Bogachiel and the Quinault are just a few of the incredible rivers that would be forever protected under this legislation.

These rivers are extraordinary in so many ways, including in the amount of rain that falls annually in their watersheds and the massive size of the old-growth trees that rest in some of the logjams along their banks. The “OP,” as locals call the Olympic Peninsula, is also where I caught my first steelhead with my older brother in 1999. Spend a day on these rivers and you really feel a sense of awe. Immersed in the moss-covered canopy and torrential rain-swollen rivers has felt to me at times like going back in time.

NOLICHUCKY: The Noli as the Nolichucky River is affectionately called, is a gem located in Tennessee and North Carolina that is home to a 7-mile, 3,000-foot deep gorge flowing through National Forest land that has been proposed for Wild and Scenic. This whitewater stretch has a dozen class II-IV rapids. The Forest Service has found the river “eligible,” recognizing its Wild and Scenic potential and providing administrative protection to the Nolichucky.

Some ask why we need to go the extra mile to permanently protect the Noli, since it already enjoys some temporary protection. One of the river’s chief advocates, Kevin Colburn of American Whitewater, put it best, “Just because you’re engaged doesn’t mean you should never get married.” We are hoping Sen. Richard Burr (R-NC) of North Carolina, who is retiring in 2022 and who has introduced bills in Congress to protect North Carolina’s New and the Perquimans rivers as Wild and Scenic will champion the Noli as one of his final acts in the U.S. Senate.

This is really just a snapshot. Development of Wild and Scenic proposals is underway on rivers across the nation. In California alone, Representatives Huffman (D-CA), Carbajal (D-CA) and Chu (D-CA) are championing a number of Wild and Scenic bills, including the Northwest Mountains and Rivers, San Gabriels and Central Coast proposals, which total 684 miles of new Wild and Scenic River miles.

In Michigan, we recently completed an assessment of Wild and Scenic potential. The state, known for its lakes, has a number of rivers worthy of protection, including the Huron, the Maple and the Brule. In Virginia, early-stage conversations about potential river reaches are ongoing.

In addition to this inspiring momentum, we’re starting to think bigger. Recently, I’ve been working with International Rivers Network, The Nature Conservancy, WWF and others to help develop strategies for durable river protections internationally, informed by our experience with the Wild and Scenic Rivers System. In one positive development, the International Union for Conservation of Nature recently developed language to build an international support network of protected river systems akin to the Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

As part of our 2021 Blueprint for Action, American Rivers is calling on the Biden administration to make protecting rivers a priority as part of the President’s commitment to protecting 30 percent of Earth’s natural areas by 2030 (30 x 30). We will continue to provide the strategic vision, advocacy and outreach needed to pass the legislation currently under consideration.

The American Society of Civil Engineers recently released their new Report Card on America’s Infrastructure. And while America’s infrastructure receives a C- overall, our water infrastructure is faring far worse: stormwater infrastructure gets a D, wastewater infrastructure gets a D+, while drinking water leads the pack with a C-. The ASCE report is just one indicator of America’s need to look at its priorities and re-invest in basic necessities. And nothing is more necessary than clean water.

The recent American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 is a good start at tackling this problem. The legislation directs $500 million for grants to States and Indian Tribes to assist low-income households pay for drinking water and wastewater services. The financial burden of these services often has a dramatic impact on low-income households who are required to allocate a greater percent of their income. The legislation also broadly makes $350 billion usable for “necessary investments” in water and sewer infrastructure.

While this funding is a good start, it is temporary and doesn’t fully get at the root of our clean water infrastructure challenges. A recent water infrastructure proposal, titled the Water Quality Protection and Job Creation Act of 2021 invests $50 billion over five years in direct water infrastructure investment. Key to this program is that it invests $40 billion to capitalize low-interest rate loan programs for municipalities while also allocating $4.5 billion in grants to handle sewer overflows and water pollution control programs. The success of this Act is its balance of low-interest loan programs (which are a critical component to maintaining water infrastructure) and grant programs for low-income communities who often don’t have the financial security to procure an infrastructure loan.

When it comes to funding infrastructure, there are some key principles we need to take into account:

- Invest in water – Too often our infrastructure funding prioritizes energy and transportation and leaves water behind. Water is largely dependent on strained local funding, which often isn’t enough to meet the clean water needs of those communities. To overcome this funding gap, water infrastructure needs federal and state investment.

- Focus on impacted communities – Because water infrastructure depends on local funding, low-income communities often struggle the most to make infrastructure investments. Even in cities that can afford more local infrastructure funding, commonly the lowest income communities (often communities of color) still don’t get the investment they need. Federal infrastructure legislation must ensure these communities get the investment they need.

- Invest in natural solutions – Natural infrastructure solutions encompass a broad range of approaches that are cost effective, climate smart ways of addressing infrastructure challenges. In water infrastructure, these practices play a key role in complementing traditional concrete-focused infrastructure, that is often more expensive and less adaptable to changing climate trends. The Clean Water for Green Infrastructure Act is a great way to start building this key piece of water infrastructure.

- Remember the source – Much of our drinking water comes from rivers, and most of our wastewater ends up back in the same rivers. When investing in infrastructure, we need to make sure we are protecting naturally functioning rivers and water quality. Rivers are significant economic engines for the country, investing in them is also helping support the communities they run through, in so many ways.

We have a long way to go to build back our national water infrastructure. Natural, sustainable and equitable water infrastructure is the best way to support healthy communities and healthy rivers.

Almost two months into his new Administration, President Biden has taken important steps to address the issues of justice, the economy, public health and climate change. In late January, he signed an executive order putting climate change at the center of both domestic and foreign policy. This order includes things like rejoining the Paris Climate Agreement, incorporating environmental justice into federal agencies’ missions and identifying how to ensure climate resilient solutions like natural infrastructure are incorporated into federal agency plans and programs. He’s also committed to reversing, rescinding or replacing a number of harmful regulatory rules the Trump Administration established that weaken environmental protections, including the Navigable Waters Protection Rule — also known as “The Dirty Water Rule.”

As a part of the most recent COVID relief bill, The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, measures were taken to assist every American on a number of topics – including water. In President Biden’s first major piece of legislation, he set a tone of inclusiveness and showed a glimpse of his plans to address environmental injustices. The bill allocates $500 million for grants to States and Native American Tribes to assist low-income households. Projections show that by 2022, one third of Americans will not be able to afford their monthly water bill, and Covid-19 has made water affordability even more critical and challenging at the same time. Additional funding ($30 million) has been allocated to the Bureau of Indian Affairs to provide and deliver potable water to Tribes across the country. These are only some initial steps to protect and restore our river and water systems, but they are essential in making our communities more resilient.

From investing in clean water and healthy rivers to removing dams, addressing flooding and community health and providing renewed support for the Wild and Scenic River Act, we turn to American Rivers’ resident experts to learn about short and long term actions the new administration can take to improve the health and long-term resilience of the rivers we love and the communities that rely on them.

As the Biden Administration turns their attention towards long-term solutions for rebuilding from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s essential any future infrastructure or economic stimulus bill include investments in improving water infrastructure, flood management and watershed restoration. In American Rivers’ report, Rivers as Economic Engines, we call on Congress to invest $500 billion over 10 years to protect and restore our rivers and water systems. We recommend a framework that prioritizes investment in three main areas:

- Improve Water Infrastructure ($200 billion over 10 years) and encourage “One Water” solutions to maximize economic, social and environmental benefits. This includes ensuring safe and affordable clean water and sanitation – particularly in Black, Indigenous, Latino and other marginalized communities – by funding the improvement of water systems, and prioritizing investments that focus on green infrastructure and water efficiency.

- Modernize Flood Management ($200 billion over 10 years) to incentivize a shift from outdated flood management policies to a multi-benefit approach that protects communities, ensures public safety, and restores river health. This includes incentivizing natural infrastructure solutions for flood management and community resiliency and ensuring flood management plans that include climate resiliency planning and prioritize natural infrastructure or nature-based solutions.

- Restore Watersheds in Our Communities ($100 billion over 10 years) to restore rivers, make agriculture more water efficient and sustainable and improve recreation opportunities. This includes prioritizing integrated water management planning, incentivizing agricultural improvements including updating irrigation infrastructure, and developing a new 21st Century Civilian Conservation Corps that will restore river and riparian habitat and improve recreational access.

These investments will not only enhance our environment, make communities more resilient and ensure more equitable access to clean water, but they will also create the jobs we need to build back better.

The House has also introduced HR. 2 “The Moving Forward Act”. This legislation is for $1.5 trillion to help rebuild American infrastructure — addressing roads, bridges, and transit systems, but also schools, housing, and broadband access. The legislation also includes over $65 billion for improvements to safe drinking water and wastewater systems and needs. If passed, these investments will help respond to the critical water needs of underserved, Indigenous and communities of color.

We have an historic opportunity to restore rivers and clean water while building back better, stronger and more equitably from the impacts of COVID-19. Tune into our most recent episode of We Are Rivers to learn more about American Rivers’ priorities for the Biden-Harris administration and the opportunities to invest in solutions that make everyone stronger.

This blog was co-authored by Emma Reesor, Executive Director of the Rio Grande Headwaters Restoration Project and Fay Hartman, Conservation Director Colorado River Basin with American Rivers.

In south central Colorado, the Rio Grande River ties together generations of people and communities across the San Luis Valley. Braided together by shared ethics of caring for land and water, everyone in the San Luis Valley depends deeply on the Rio Grande – for their livelihoods, the rich diversity of wildlife, and activities they enjoy, as well as their connection to the rich history of people who have come before them. Water management has always been a challenge in this arid region, and our new film, Through Line, showcases a new generation of water managers, who are facing challenges like climate change, growing pressure to the water supply, and renewed water export threats head on.

“Everything we do revolves around it. The river is the community. It makes us whole. It completes us,” says 4th generation San Luis Valley farmer Doug Messick in Through Line.

Today, the Rio Grande is more important than ever, providing critical benefits for the community from water for agriculture and recreation to important wildlife habitat and clean drinking water for local and downstream communities. Like many other southwestern rivers, the Rio Grande faces many challenges, including degraded habitat, over appropriation of water, and decreasing flows caused by drought. Communities across the San Luis Valley recognized these threats and developed the Rio Grande Headwaters Restoration Project (RGHRP) in 2001, to restore and conserve the health of the Rio Grande for the diverse ecological and human communities who depend on it. Over the past 20 years, the Restoration Project has partnered with farmers and ranchers, state and federal agencies, local communities, and other non-profits to address challenges facing the river through holistic restoration projects that improve fish and wildlife habitat, agricultural water use, recreation opportunities, and overall river health.

The San Luis Valley community has come together to restore the Rio Grande because the region depends on this shared and finite resource. Through Line showcases the many ways the river provides for the community – benefits that extend beyond the river corridor across the entire Valley, as water flowing in rivers and streams is inherently linked to the groundwater below.

Today, a new challenge faces the river and community, in the form of a water export proposal. Renewable Water Resources (RWR) is proposing to pump 22,000 acre-feet of water from the San Luis Valley’s confined aquifer and export it from the Valley to urban communities on Colorado’s Front Range. This proposal would reduce aquifer sustainability, permanently dry up at least 20,000 acres of farmland, and negatively impact the rivers, streams, and wetlands that give life to the local communities and wildlife populations. The San Luis Valley is united in opposing the water export because it threatens the very backbone of the community, its water supply.

Through Line celebrates the importance of protecting and restoring the Rio Grande. It describes both the history and future of water management in the Valley through the voices of modern managers—specifically a growing number of women in a historically male-dominated profession— working together to ensure that the needs of communities are met alongside the needs of the river itself, underscoring that while the challenges may be many, “the future health of the Rio Grande is in good hands” as Karla Shriver describes. The film touches on just how detrimental the water export proposal would be for the Valley, the river, and all that depend on it.

“If our little community doesn’t work together to protect our land and water, everything’s lost,” says Ronda Lobato in Through Line. And she’s right. The Rio Grande and San Luis Valley are a magical part of Colorado and the southwest. A healthy, flowing Rio Grande ensures this special place will continue to thrive today and in the future.

Late last fall, a new dam and reservoir project was proposed on the East Fork of the Virgin River in southwestern Utah, just upstream from Zion National Park. The proponents of the project, Kane County Water Conservancy District, argued that the proposed $30 million dam would be relatively “small” by dam standards (a mere 90 feet high!) and the resultant Cove Reservoir would impound just over 6,000 acre-feet of water. But all dams can have outsized impacts on free-flowing rivers and the fish, wildlife, and ecosystems that depend upon them.

The East Fork Virgin River supplies water to Utah’s first Wild and Scenic River, the Virgin River, which carved the precipitous canyons of Zion National Park. The river is also home to two endangered fish (the woundfin and Virgin River chub) and the endangered Southwestern Willow Flycatcher. American Rivers was skeptical that a new, nine-story dam would benefit these species, as was claimed by developers in the project proposal and Draft Environmental Assessment (EA). You may know that an EA is an abbreviated environmental analysis meant for projects that would not cause significant, adverse impacts, but projects that do have the potential to cause significant harm often require a more thorough and lengthy Environmental Impact Statement (EIS).

On February 24, the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) determined that due to the extensive concerns brought in the comments submitted during the Draft EA, the agency would require a full EIS for the proposed Cove Reservoir project later this spring. The EIS process will give those who care about the Wild and Scenic Virgin River, Zion National Park and endangered species more opportunities to weigh in on this dubious, taxpayer-funded project, which has been designed to benefit just 6,000 acres of agricultural lands in Kane and Washington counties. American Rivers, along with our local partners, have discovered that nearly two-thirds of those agricultural lands that may benefit from the project have already been developed into commercial and residential development projects, bringing the legality of the project into question as well.

We realize that environmental analyses of proposed dam projects can be technical, full of jargon and confusing. But we’ve got your back: The comments submitted by American Rivers and our partners have slowed this damaging project and has positioned the East Fork Virgin River to receive the in-depth environmental analysis it deserves. This means that there will be more opportunities for you to weigh in on this proposed project later this spring. In the meantime, you can keep track of the Cove Reservoir Project through NRCS on this website.

If you had lived in Oregon in late 2019, and perhaps you did, you would have received an unprecedented invitation from Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR). The gist of it was this request: “Tell me about the rivers you love. Tell me the rivers and streams with the cleanest water, the best recreation, and that are the most important to fish and wildlife. Tell me which rivers you want us to protect.”

In the months to follow, Wyden and his team, with help from partners like American Rivers, collected nominations for streams and rivers that Oregonians care to protect and preserve. And Oregonians definitely care. Wyden’s call was met by more than 15,000 nominations. Everyone from hunters and anglers to outdoor businesses and elementary school kids weighed in asking Sen. Wyden to protect their most cherished rivers and streams including those in the McKenzie, the Deschutes, the Grande Ronde, the Rogue, Illinois and Nestucca river watersheds. Importantly, ahead of this public call, Sen. Wyden worked at the government-to-government level to invite and incorporate input from sovereign tribal nations.

The momentum from these asks and the feedback received has carried forward and culminated in the recently introduced River Democracy Act, the most meaningful Wild and Scenic Rivers effort since the act was passed in 1968 through a bipartisan vote in the Senate of 92-8.

A Wild and Scenic is sort of like the national park system for rivers. It protects the free-flowing nature of rivers and safeguards them against damming and harmful development, while still leaving room for river management that is in line with river conservation. A Wild and Scenic designation also protects 1/4-mile of land on each side of a designated river, making this a powerful tool for protecting the full suite of resources — habitat, water, food — that are so important for wildlife and overall watershed health.

The River Democracy Act would protect over 4,600 miles of rivers and streams in Oregon but Sen. Wyden is protecting far more than miles of rivers or acres of high-value riverside land. His sweeping act defined by an unprecedented public process would protect Oregon’s most valuable natural resource, which provides clean drinking water, fish and wildlife habitat and supports Oregon’s outdoor recreation economy. According to Earth Economics, that economy supports 224,000 jobs statewide and generates $15.6 billion in consumer spending. The legislation supports good hunting, fishing and other outdoor recreation, and supports small businesses as more and more Oregonians find refuge in the outdoors.

The potential benefit of the River Democracy Act is huge. And, inspiring. Especially when you consider that most of the streams up for protection are small, easy-to-neglect tributaries that are vital to the health of better-known rivers.

When I saw the call, my family and I crammed into our 2005 Toyota 4-Runner and wandered our way into the Oregon wilds to find the small streams that we thought should be protected. Watching my kids discover these lesser-known but incredibly vital creeks moved me. In so many ways, small streams — even tiny ones — are like salmon to a grizzly bear. Rivers may be the more charismatic megafauna, and for good reason. But here’s the thing: Without all the little streams, bigger rivers would stop chugging along — they simply wouldn’t exist at all.

The streams we fished, floated, dipped in and marveled at are rare havens, where creatures escape the impacts of climate change, and farmers and ranchers make sustainable livings. They provide drinking water and offer refuge — for fish and birds and mammals, and for us. Every single one is worthy of its own blog post, story, rallying cry and protection.

Wyden said: “Rivers and streams are Oregon’s lifeblood, providing clean drinking water for our families, sustaining our thriving outdoor recreation economy, and nurturing the quality of life that brings new investments, businesses and jobs to our state.” And it’s true — not just for Oregon, but also for rivers and their tiny counterparts across the nation.

The River Democracy Act does something else that’s important, and timely. It recognizes the importance of protecting sources for drinking water — it sees the forest and the threats posed to the forest by climate change. The bill establishes a new national source for funding to restore rivers that have been devastated by fire and that provide drinking water, such as those that burned in Oregon in 2020.

And yet, even if the River Democracy Act becomes law, the nearly 7,500 miles of rivers and streams protected in Oregon will still represent a miniscule fraction of Oregon’s 110,994 total miles of rivers. Just 0.004 percent of the 3.5 million miles of streams and rivers in this country are protected as Wild and Scenic. Sure, a Wild and Scenic designation isn’t the only way to protect these rivers. But it is a powerful and arguably underutilized tool.

And right now, river protectors have momentum on our side. Biden’s pledge to advance the protection of at least 30 percent of the nation’s lands and waters by 2030 comes out of a growing recognition of the immense value these resources provide, and the myriad ways they are threatened. Wild and Scenic protections like the River Democracy Act move this vision forward.

The River Democracy Act still has to make its way through Congress and onto the President’s desk. But legislation like this one, and the process that led to it, move us in the right direction. We have to be ambitious and bold when it comes to our rivers and streams. Because as ambitious and bold as we might be, the threats to rivers are doubly perilous. It’s a David and Goliath situation. And while Goliath may not know it yet, he needs healthy rivers and streams, too — so it’s a battle David just might win.

This blog was written by Page Buono & Sinjin Eberle, American Rivers Communications Director, Intermountain West.

Over the last few weeks, we’ve focused our attention on the recent study published by the Center for Colorado River Studies about the future of the Colorado River, given some alarming new data synthesized by the Center. You’ll likely recognize the authors—Kevin Wheeler, Jack Schmidt, Eric Kuhn, Brad Udall and others—who are no strangers to ongoing dialogue about the river. In our first post, we covered the broad takeaways, the potential ramifications of the study’s finding on water management in the West, and on the importance of the inconvenient science it elevates. In the second post, our “Changed River” edition, we let the line “The Colorado River has been profoundly altered from its highest reaches to its delta” percolate and came out even more committed to the preservation of the river and inspired to consider and address new challenges revealed by the study that will demand even more aggressive action on behalf of the river.

In this, our “Climate & the River” edition, we’ll highlight findings from the study that underscore how important it is that, as we look to the future, we model future hydrology not only by understanding the past, but by looking ahead to the impacts of back-to-back and longer-term droughts paired with warming temperatures that precipitate aridification. As climate scientist Brad Udall likes to say, it’s a “hot drought,” where warmer temperatures are leading to less water in the river, even if precipitation is actually remaining roughly the same.

The stakes of including, or ignoring, the likelihood of a hotter and drier future in our decision making are high. Authors open their study with this quote for a reason:

“The likelihood of conflict rises as the rate of change within the basin exceeds the institutional capacity to absorb that change.” Wolf, A. T., S. B. Yoffe and M. Giordano (2003).

If you’re eager for the takeaways, you can skip to the bottom of this post. If you’re curious about how they arrived there, and why, read on!

The assumptions we make to inform future management are critical, and when it comes to predicting future hydrologic conditions that answer the questions: “How much water will be available? In what form? And when?”, it is irresponsible not to model and plan—to the greatest extent possible—for the conditions climate science predicts.

To that end, the authors compiled diverse sets of data to represent a range of past and future conditions and applied them to the management alternatives that we highlighted in the first blog of this series. The findings of their analysis underscore discrepancies between projections that look solely to the past, those that ground themselves in recent hydrologic regimes, and those that forecast to the future based on various climate projections.

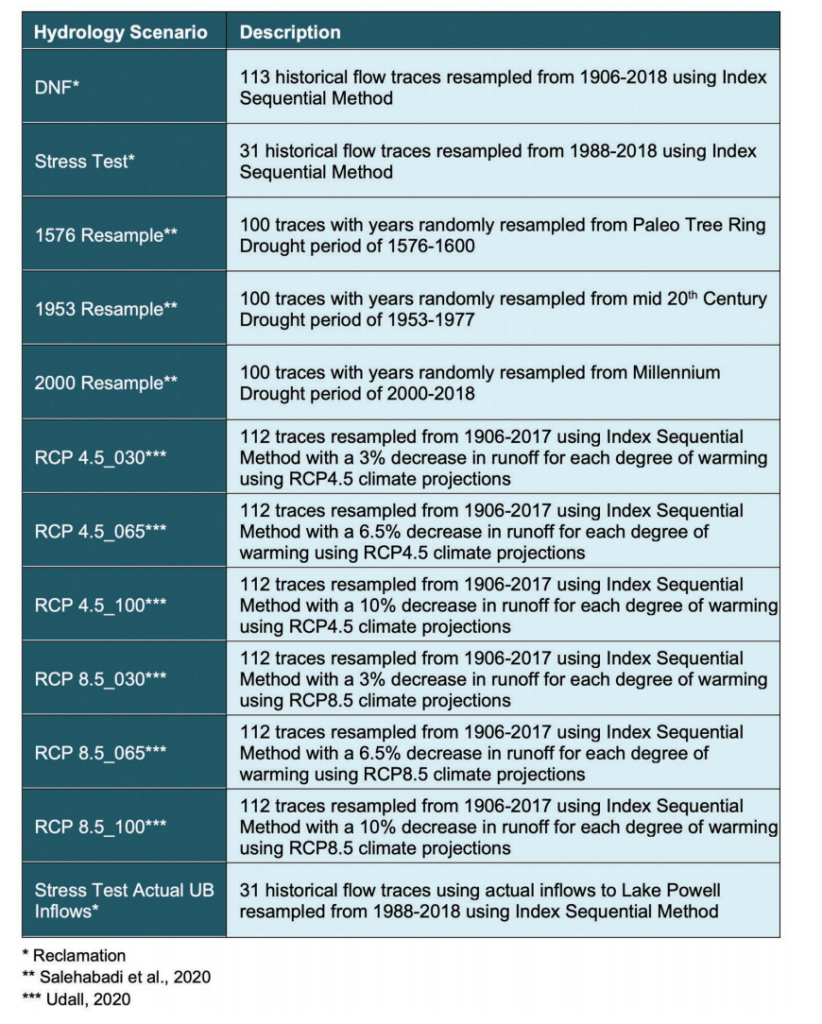

Currently, the Bureau of Reclamation utilizes two different hydrologic model sets, one called the Direct Natural Flow (DNF) and the other called Stress Test hydrology. Each model is derived from the average flows across different periods in history. The DNF model relies on estimated natural flows from 1906-2018. Authors of the study point out that this 113-year period includes what’s referred to as the “20th century pluvial period” from 1906-1929, an unusual, bountifully wet period, from a hydrologic perspective. According to Udall, the patterns represented by the DNF data are unlikely to re-occur in current management timeframes. The Stress Test hydrology skips this period and jumps to a 31-year range between 1988-2018, which includes both high flow years, and years of drought beginning in 2000 – what the authors refer to as the ongoing “millennium drought.” In addition to those, authors integrated or developed the following forward-looking data sets:

Now, if that looks super technical, it’s because it is! These detailed and diverse data sets allowed the authors to model unique scenarios, including three different scenarios of extended drought, all of which have occurred in the past, and for decreases in runoff associated with the anticipated effects of aridification. They chose these hydrology sets to test alternative management strategies under long periods of low runoff, and the kind of runoff we might see under increasingly warmer temperatures, both of which the authors describe as “…plausible futures that should be considered in planning purposes.” The range of futures hydrology predict average flows at anywhere from 14.76 million acre feet (maf), the flows modeled under the DNF hydrology scenario, and down to 9.71 maf a year under the RCP 8.5_100 data set.

The authors integrated these hydrologic scenarios alongside multiple scenarios for consumptive use and management in an attempt to better understand possible future impacts to the Colorado River, and those who depend on it. As the study points out: there is more work to be done here, and the authors hope this inspires future studies that imagine more management scenarios. But even though they aren’t comprehensive, the overall observations the authors make after running these scenarios are prescient, and compelling.

In a nutshell, the authors state that “climate change is causing flow declines, and additional declines are likely to occur,” and point to the following as both evidence and inspiration for more creative thinking as we plan for the future:

- Between 2000-2018, flows in the Colorado River were approximately 18% less than from 1906-1999.

- The ongoing drought and low-flow years that we’ve seen since 2000 are, quite likely, not going away any time soon. And even they may not be accurate representations of the future because as temperatures rise and catalyze further aridification of the region, more dramatic declines in flows are likely.

- Given the unpredictability of the future paired with the immense likelihood of less, not more water, is it incumbent upon water managers and users to plan and think proactively and creatively.

- The DNF hydrology predicts approximately 2 maf/year more than we’ve seen the last 20 years, while the RCP 8.5_100 hydrology predicts nearly 3 maf/year less than we’ve seen in the last 20 years. As Udall says, that 5 maf range is, frankly, enormous.

Authors warn that these conditions paired with unrealistic aspirations for development of future flows will “result in a difficult, basin-wide reckoning.” Incremental tweaks to the management of the river may no longer work, and the study calls upon us to think now about a drier future, not to wait until we’re there. And perhaps to acknowledge that, in many ways, we already are.

Despite the challenges of working through a pandemic, river restoration practitioners continued to pursue dam removal projects in 2020 to revitalize local economies and communities and reconnect 624 upstream river miles for fish, wildlife and river health. Sixty-nine dams were removed in 2020 across 23 states, including: California, Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington and Wisconsin.

A total of 1,797 dams have been removed in the U.S. since 1912. The states with the most dam removals in 2020 were Ohio (11), Massachusetts (6) and New York (6).

Local partners, engineers and construction crews worked under extraordinary circumstances to complete these projects, delivering a wide range of benefits to their rivers and communities. For example, on the Middle Fork Nooksack River near Bellingham, Washington, removing a water diversion dam and installing a new water intake opened 16 miles of habitat for salmon, restored cultural resources, and ensured a sustainable supply of clean water for the city. The project, an effort of American Rivers, the Nooksack Indian Tribe, Lummi Nation, City of Bellingham, Paul G. Allen Family Foundation and others demonstrates the power of public-private partnership and innovative solutions to infrastructure challenges.

More than 90,000 dams block rivers in the U.S. Dams harm fish and wildlife habitat and ecosystem health and can pose safety risks to communities. The failure of Michigan’s Edenville Dam in May 2020 was the latest high profile example of the threat aging, outdated dams pose to public safety. A recent UN report highlighted the growing risk of aging water infrastructure.

American Rivers’ report, Rivers as Economic Engines, outlines how investing in water infrastructure and river restoration creates jobs and benefits the economy. For example, according to a study by the University of North Carolina, the ecological restoration sector directly employs approximately 126,000 workers nationally, and supports another 100,000 jobs indirectly, contributing a combined $25 billion to the economy annually.

On a much larger scale than the projects featured on the 2020 list, Congressman Mike Simpson (R-ID) recently shared a vision for infrastructure investments in the Pacific Northwest that includes removal of four dams on the lower Snake River, which would be the biggest river restoration effort in history. While details need to be addressed before legislation can be enacted, Congressman Simpson’s proposal illustrates how river restoration can be part of transformational solutions that include clean energy, agriculture, job creation and economic revitalization.

Learn more about this year’s dam removal projects:

- View the national map of dam removals

- Access the American Rivers dam removal database

- Take action to support federal investment in river restoration

Some other interesting projects from around the country in 2020 include:

NORTHEAST: South Branch Gale River Dam, South Branch Gale River, New Hampshire

The South Branch of the Gale River was blocked by a 21-foot high concrete and earthen dam in Bethlehem, New Hampshire, in White Mountain National Forest. The dam was a complete barrier for fish and disrupted natural riverine processes. The Littleton Water and Light Department (LWLD) constructed the dam and associated infrastructure in 1955 for water supply; however, it was no longer in use and had become a maintenance burden. In keeping with the original Special Use Permit from the Forest Service, the dam had to be removed if it was not in use. Removal of the dam was a priority as measured under several river connectivity prioritization methodologies and will restore connectivity to approximately 15 miles of river above the dam and approximately 21 miles of river downstream of the dam. Working together on this project, the partners included the LWLD, American Rivers, New Hampshire Department of Ecological Resources, New Hampshire Fish and Game, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, The Nature Conservancy, and the U.S. Forest Service.

SOUTHEAST: Burson Lake Dam, Reedy Creek, South Carolina

This project, led by staff at the Francis Marion-Sumter National Forest, removed a dam that had created a recreation lake because the spillway was undermined. This earthen dam was built in 1990, and its spillway was damaged by spring 2020 rain events. The U.S. Forest Service (USFS) decided to remove the dam due to increased risk of failure during 2020 hurricane season (before scheduled repairs could be completed). USFS repurposed part of funds intended for culvert replacement by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to pay for dam removal. A USFWS restoration team did the construction. USFS intends to use this as a demonstration site to show dam owners in the Piedmont/foothills what a restored site looks like. This project restored the aquatic community and potential rare species habitat for Bartram’s bass, removed a safety hazard, eliminated ongoing maintenance costs to taxpayers, and promoted greater climate change resilience.

MIDWEST: Elkhart River Dam, Elkhart River, Indiana

The Elkhart River Dam, an approximately 8-foot-tall low-head dam, was built around 1890 to increase the elevation of the river to divert water into raceways that were used to power industry in downtown Elkhart, Indiana. Over time as development occurred, these raceways filled and the dam no longer served a purpose. The dam gave rise to the name of Waterfall Drive, the street located adjacent to the former dam. The former dam was located approximately one-half mile upstream of the Elkhart River’s confluence with the St. Joseph River. With the Elkhart River being the largest tributary of the St. Joseph River, this dam served as a significant barrier to fish migrating out of the St. Joseph River. The dam’s removal reconnected 40 miles of upstream habitat, allowed for the recolonization of 16 species of fish in the Elkhart River and population integration for approximately 50 fish species, including endangered or threatened species (e.g., greater redhorse, longnose dace, and northern brook lamprey).

NORTHERN ROCKIES: Rattlesnake Creek Dam, Rattlesnake Creek, Montana

This dam removal reestablished the connection between the Rattlesnake Wilderness at the headwaters and the Clark Fork River for the first time in more than 100 years. Ultimately, all manmade structures will be removed, 1,000 feet of stream channel will be restored, and 5 acres of wetland and floodplain will be created. A public-private partnership was formed to accomplish this project between the City of Missoula, Missoula Water, Trout Unlimited, the Watershed Education Network, and the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks.

NORTHWEST: Pilchuck River Diversion Dam, Pilchuck River, Washington

The Tulalip Tribes worked with the City of Snohomish and many project funders to completely remove two adjacent dams on the Pilchuck River in Washington State primarily to provide unimpeded threatened and endangered species fish passage to over 36 miles of pristine upstream habitat for the benefit of Chinook, coho, chum, and pink salmon, steelhead trout, bull trout, cutthroat trout, and a variety of other aquatic species. The project is expected to increase fish stocks, increase safety, reduce risk from potential dam failure, and increase recreational opportunities.

As we teased in a blog last week, we’re back to continue breaking down the compelling, and quite frankly, sea-changing recent study coming out of the Center for Colorado Rivers Studies at Utah State University. In it, we highlighted key findings from the study’s authors, Kevin Wheeler, Jack Schmidt, Eric Kuhn, Brad Udall and others. If you missed the initial release, you really should take a few minutes to at least read the Executive Summary, as it does a great job illustrating the challenges that the entire Colorado River ecosystem faces in the face of climate change. We also took the opportunity to pivot off of a blog post by John Fleck, author and Director of the Water Resources Department at University of New Mexico, about the same study.

At the end of our post, there was what amounts to a Top 10 List of key takeaways from the Center’s white paper, and a few of them seemed especially relevant to American Rivers body of work in the Colorado Basin, and to how we are thinking about the future of the Colorado River.

We can’t stop thinking about the line, “The Colorado River has been profoundly altered from its highest reaches to its delta,” which is something we all know, but describing it in that way is significant. There can be no argument that there has been major alteration to the river, from the highest headwaters trickling down from Poudre Pass (and the Grand Ditch, built between 1890 and 1936) all the way to the first dam built on the Colorado River, Laguna Dam near Yuma (1903) on to Morelos Dam on the Mexican border. Major impoundments and diversions like Flaming Gorge and Fontenelle on the Green, Granby Dam in the Colorado headwaters, tributary dams like Ruedi on the Frying Pan and the Aspinall Unit on the Gunnison, and yes, Lakes Powell and Mead, whose storage levels drive the vast majority of the policy rules, compacts, and guidelines that manage the river. We also should acknowledge two other aspects of this changed river – that ecosystems like the Grand Canyon, Glen Canyon, Black Canyon, and the San Juan are changed due to these alterations, but also that nearly 40 million people, a 1.4-trillion-dollar economy, and millions of jobs depend on the sum of all of these parts.

Is the system altered? Absolutely. But does that mean it’s dead and that we should not keep doing whatever we can to preserve it? Absolutely not.

The Colorado River system is highly managed, strained, stressed, and challenged, but is also one of the most loved, revered, enjoyed and sacred rivers in the world. Tribal communities whose lands are currently located hundreds of miles from its banks still call the Colorado River sacred. Millions upon millions of visitors, from across the country and around the globe, from all walks of life, gaze onto it’s waters every year. Tens of thousands of people raft, fish, swim, kayak, and yes, drink, it’s flowing bounty. It preserves life in so many ways, but the most prominent way is in our hearts. The Colorado River is one of us, and we are it.

In part, that is why the statement from the white paper was so striking. Even if you are not a dedicated river conservationist, you know that the Colorado River has been providing so much, for so long. Now with the onset of a warming climate, even the baseline amount of water the river carries is declining – and will decline over the next 30 years. Our laws and policies around the river were built on a totally different climate, with a totally different set of pressures, and demands, than what we have today.

The science matters, and teasing out the detail, as well as the topline implications from this report will take time, and it will catalyze critical debate, and demand hard choices. American Rivers, our partners, and our team here in the Colorado Basin is ready, and enthusiastic, about confronting and helping to solve the challenges facing the Colorado River. But we can’t solve these challenges alone. Ultimately, we need everyone who relies upon, and who loves the Colorado River on board. Hopefully you are too!

Next week, we will be teasing out more from the report around how climate change is causing flow declines and that additional declines even more likely to occur looking forward. Stay tuned!