The Chattooga River has acquired a number of distinctions and nicknames over the years, including the honor of being considered by many as “The Crown Jewel of the Southeast.” In South Carolina, the Chattooga is considered one of the state’s “Seven Natural Wonders” and is featured prominently during the annual SC-7 Expedition. It begins as small streams, high on the slopes of the Appalachian Mountains near Whiteside Mountain in North Carolina. Nurtured by other streams and abundant rainfall, it travels 50 miles until it ends at Lake Tugaloo between South Carolina and Georgia.

To say the Chattooga River is a popular destination would be quite the understatement. On any given day, the Chattooga is abuzz with activity as people seek to enjoy the river through whitewater rafting and kayaking, flyfishing, and swimming, as well as hiking and camping in the forests that surround the river. You can sense the energy in the atmosphere when you are standing along the Chattooga, whether it is the palpable excitement exuding from thrill seekers as they prepare to launch their boats into the turbulent waters; the serene silence as a solitary angler casts a line into the river; the carefree feeling as a family splashes around along the river’s edge; or the contemplative wonder as folks take in the beauty of one of the many waterfalls along the river corridor. With all this activity, it can be difficult to imagine how not so long ago the Chattooga was practically unknown to the outside world.

Centuries before European settlement of the area, the Cherokee and other tribes living along the Chattooga served as stewards of the river and its vital natural resources. The canebrakes along the river, the supply of fish and other aquatic resources, and the abundant forest resources played important roles in the cultural life of those who called this area home. A small Cherokee settlement called Chattooga Town was located along a well-used trading path and adjacent to an important river crossing that connected Cherokee communities on both sides of the Chattooga River. Even after European settlement, the rugged landscape of the area helped keep local communities small and isolated even well into the 20th century and the local knowledge of the river was not as readily available to those who lived outside the region. That all began to change as word of the Chattooga River started to spread beyond these local communities.

Although the Chattooga caught the attention of theater goers who watched the movie Deliverance in 1972, which prominently featured the river, by that point the Chattooga was already starting to see a rise in awareness within certain circles, especially among environmentalists and outdoor recreationalists. In fact, when Congress passed the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 the Chattooga was specifically identified as one of 27 rivers across the country to be studied for possible future inclusion in the new National Wild and Scenic River System. Following the study, it was concluded that the Chattooga was indeed eligible and on May 10, 1974, the Chattooga River became the first river in the Southeast designated as a Wild and Scenic River (WSR).

So what is Wild and Scenic River designation and why does it matter? The National Wild and Scenic Rivers System was created to preserve certain rivers with outstanding natural, cultural, and recreational values in a free-flowing condition for the enjoyment of present and future generations. When a river is added to the National System, it is given a classification—wild, scenic, or recreational, which are measures of the level of development along the river at the time of designation (the Chattooga WSR has sections of the river representing all three classifications). Additionally, the Chattooga WSR is managed to preserve the following “Outstanding Remarkable Values:” ecology, geology, history, recreation, and scenery (for more details visit this website.) Commenting on the importance of WSR designation for the Chattooga, CEO of the outfitter Wildwater, Jack Wise states that “The Chattooga River would be a very different place today without the direct actions of a few pioneers. Today’s beauty and other special qualities of the Chattooga National Wild and Scenic River are due to the foresight of a coalition of river runners, state, and national legislators with the help of the US Forest Service.”

Some of the influential individuals and organizations during this early effort included Claude Terry, co-founder of American Rivers (and consultant and stunt double for John Voight in Deliverance), who convinced Jimmy Carter, governor of Georgia at the time, to join him in running the infamous Bull Sluice rapid in a tandem canoe. Carter grew up in awe of nature’s wonder. But it wasn’t until he first paddled the Chattooga River that he understood the power and majesty of a wild, free-flowing stream. The Wild President, a film produced by American Rivers and NRS in 2017, tells the story of Carter’s soul-stirring journey with Claude Terry on the Chattooga, and how the experience motivated him to push for legislation that would protect 57 miles of the Chattooga River as a Wild and Scenic River, preventing any damming or other activities that threaten the rivers’ values. “Once you get to know an area, it becomes part of you, and you can’t help but want to protect it” said Carter.

Today, the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River Corridor is co-managed by the three national forests that straddle the tristate border: Chattahoochee National Forest in Georgia; Nantahala National Forest in North Carolina; and Sumter National Forest in South Carolina, which serves as the lead forest for the Chattooga WSR. As with anything of this scale and complexity, managing the Chattooga WSR involves near constant collaboration and engagement with local communities, stakeholders, and leaders in all three states. The rivers’ WSR designation and management ensures that the river remains clean, natural and free flowing. In fact, the Chattooga is one of the last remaining free flowing or un-dammed rivers in the Southeast.

Speaking of collaboration and engagement, throughout 2024 the Forest Service and community partners will be celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Chattooga’s Wild and Scenic River designation, with a specific emphasis on river stewardship. They will take the time in 2024 to reflect on the successes and the challenges of the past 50 years since the Chattooga’s WSR designation. Secondly, throughout the year they will also reengage with local communities in river stewardship through hands-on service events and projects, such as river cleanups. As they do this, the Forest Service and partners want to be intentional in connecting with underserved communities to ensure everyone has the opportunity to access and steward the Chattooga River. Finally, although 2024 is a time to celebrate an important milestone, the three forests plan to also focus on developing future stewards of the Chattooga.

District Ranger, Robbie Sitzlar from the Andrew Pickens Ranger District (Sumter National Forest) shares, “As much as we want to take the time to celebrate where we’ve been and where we are today, we know that it is critical that we continue to develop the next generation of river stewards through engaging children and families. Because, at the end of the day, each one of us has a role to play in the health of the Chattooga and with ensuring that future generations can enjoy the unique beauty and recreational experiences that the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River Corridor offers.” Throughout 2024, YOU are invited to join us in celebrating the Chattooga River and what it means to South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia and the nation. Come and enjoy all that the Chattooga WSR has to offer, while remembering that it is up to each one of us to do our part in ensuring this important resource can be enjoyed for generations to come.

To learn more about the many recreational opportunities that the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River offers and how you can get engaged with stewarding this important river, check out the Forest Service Interactive Visitor Map and visit the national forests’ websites:

- Sumter National Forest, South Carolina: www.fs.usda.gov/scnfs

- Chattahoochee National Forest, Georgia: www.fs.usda.gov/conf

- Nantahala National Forest, North Carolina: www.fs.usda.gov/nfsnc

To learn more about the National Wild and Scenic River System, visit: www.rivers.gov

Greg Cunningham worked for the National Park Service for 15 years at national parks in Virginia, Hawaii, and South Carolina. In 2022, he started with the Forest Service and currently serve as the Staff Officer for Recreation, Heritage, and Engineering for the Francis Marion and Sumter National Forests in South Carolina. He can be reached at Gregory.Cunningham2@usda.gov

Dr. Janae Davis is the Southeast Conservation Director for River Protection at American Rivers. She can be reached at jdavis@americanrivers.org.

Beneath the meandering channels that run across a Sierra Nevada meadow in spring, your eye may catch silver flashes dancing along the banks. In the Pine Creek watershed of Lassen County California, those glimmers could be Eagle Lake Rainbow Trout (ELRT), a California Heritage Trout, Species of Special Concern, and endemic subspecies of rainbow trout. These iridescent salmonids travel upstream to spawn in the meadows and cascading headwaters of Pine Creek each spring. Their journey begins as soon as the creek swells with snowmelt and spills into Eagle Lake, but the window to return is narrow and unpredictable.

Fortunately for these special trout, partners across the conservation field have come together and are working to restore their critical spawning habitat. American Rivers has been engaged in the Pine Creek watershed since 2015, and has proudly collaborated with the Lassen National Forest, Trout Unlimited, Susanville Indian Rancheria, the Pit River Tribes, and many other partners to build relationships and restore the watershed. American Rivers successfully implemented a riffle construction project in McKenzie Meadow in 2020, creating pools and riffles along the stream channel which enable ELRT to migrate upstream. In 2023 American Rivers implemented a project in Confluence Meadow to fill the eroded western channel and reactivate the flood plain along Pine Creek These projects have created critical habitat for ELRT migration and will help keep the water table higher throughout their spawning season.

But the obstacles facing ELRT are significant. While their resilience and quick growth rate make them a world-class stocking fish outside of Pine Creek, ELRT are threatened by changes in hydrology and an increasingly variable climate within their native spawning habitat. Following the arrival of Euro-American settlers, the Pine Creek watershed experienced changes in land use including grazing, road and railroad construction, water diversions, and ditching. Additionally, the watershed sits where the Sierra Nevada meets the Great Basin and experiences a drier and more variable climate than most other Sierra watersheds.

Of Pine Creek’s 35 stream-miles, only 7 flow year-round in the upper watershed. The fractured volcanic bedrock in the watershed slowly drains the lower reaches of the creek, cutting off access to the lake’s refuge until the waters rise again the following year. The seasonal connection between Pine Creek and Eagle Lake is fed by snowmelt from the high elevation headwaters. As snowpack and the timing of snowmelt become increasingly unpredictable and variable in the face of a changing climate, the critical hydrologic connection between Pine Creek and Eagle Lake doesn’t always persist long enough or at the right time for ELRT to spawn and for juveniles of the previous year’s cohort to migrate downstream to the lake. Ultimately, the shift in Pine Creek’s hydrology has contributed to declines in ELRT populations below sustainable levels and the fate of this iconic fish now depends on hatchery-based spawning.

As we continue to engage in the Pine Creek watershed, American Rivers is working to advance landscape scale watershed restoration. Last year, we took on a leadership role in convening the Eagle Lake Partnership and acquired funding to enable a Partnership framework which is effective, transparent, and inclusive. Funding at this early stage has allowed us to engage the Pit River Tribe and Susanville Indian Rancheria to co-develop a Partnership MOU and fund tribal priority projects and trainings. The inaugural meeting of the partnership was attended by over 40 individuals representing the Lassen National Forest, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, permitting agencies, funders, tribes, NGOs, private timber industry, grazers, the Lassen Resource Control District, and the local Firesafe Council. The partnership is working to develop a restoration plan for a 100,000-acre project area, which includes fuel reduction treatments, meadow and river restoration, recreation and road improvements, all while incorporating traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). This large-scale collaborative effort will help increase the pace and scale of projects which ultimately benefit native flora and fauna beyond the Eagle Lake Rainbow Trout, and Sierra Nevada ecosystems as a whole.

The challenges ELRT face are not unique and reflect many of the challenges faced by other native California salmonids. From the Klamath watershed in northwestern California to the headwaters of the Sierra Nevada, American Rivers is dedicated to working in collaborative partnership, restoring vital habitat, and providing a sustainable and lush home for fish, wildlife, and the communities that need healthy rivers.

“Without this river, we would not be able to survive,” says Vicente Fernandez, acequia mayordomo and community leader in New Mexico.

New Mexico is the state hardest hit by a recent Supreme Court ruling that left virtually all of the state’s streams and wetlands vulnerable to pollution. This federal action opens the door to potential harmful downstream impacts to the Rio Grande, Gila, San Juan, and Pecos rivers.

It threatens Vicente’s livelihood, and so many others across New Mexico.

This is why the Rivers of New Mexico are #1 in America’s Most Endangered Rivers of 2024 – our annual report that amplifies local leaders calling for solutions to urgent river threats.

This year’s report shines a spotlight on threats to clean water nationwide – for example:

- Tennessee’s Duck River, a drinking water source and hotspot for biodiversity, is at risk from excessive water withdrawals

- California and Mexico’s Tijuana River, is choked with pollution causing illness and beach closures

- California’s Trinity River, a vital source of clean, cold water for the Klamath River, is at risk from water diversions

- Connecticut’s Farmington River, the drinking water source for nearly 400,000 people, is threatened by a hydropower dam causing toxic algae outbreaks

We chose the 2024 list of Most Endangered Rivers with support from partners nationwide. Groups and individuals shared their nominations, and as we do every year, we built the list based on three key criteria:

- The importance of the river to people and wildlife

- The magnitude of the threat

- A decision point in the coming year that the public can influence

This is the 39th year of America’s Most Endangered Rivers, and it has a track record of results. By teaming up with local partners, generating significant media attention, and galvanizing the public to contact decision-makers and call for solutions we make a big impact together. Over the years, this campaign has helped stop pollution in the Buffalo National River, and it helped protect the Boundary Waters from mining. It played an important role in protecting Wyoming’s beautiful Hoback River, and it has contributed to dam removal efforts from the Penobscot to the Klamath to the Eel.

We’re confident that with your help, we can keep the positive momentum going.

You can learn about America’s Most Endangered Rivers of 2024 by reading the report and watching our video presentation. We also hope you will take action for the rivers, and support our partners – the heart and soul of this campaign.

And, if anyone asks you why protecting small streams is so important for ensuring clean drinking water in New Mexico and nationwide, you can introduce them to Splashy – a little character we dreamed up to advance efforts to strengthen the Clean Water Act.

Stronger clean water protections at the federal level are essential to safeguarding America’s Most Endangered Rivers of 2024, and rivers everywhere.

“All water is connected. We cannot allow pollution anywhere without risk to the rivers we rely on for our drinking water,” said Tom Kiernan, President and CEO of American Rivers. “Our leaders must hold polluters accountable and strengthen the Clean Water Act to safeguard our health and communities.”

America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2024:

#1: Rivers of New Mexico

Threat: Loss of federal clean water protections

#2: Big Sunflower and Yazoo Rivers – Mississippi

Threat: Yazoo Pumps project threatens wetlands

#3: Duck River – Tennessee

Threat: Excessive water use

#4: Santa Cruz River – Arizona

Threat: Water scarcity, climate change

#5: Little Pee Dee River – North Carolina, South Carolina

Threat: Harmful development, highway construction

#6: Farmington River – Connecticut, Massachusetts

Threat: Hydropower dam

#7: Trinity River – California

Threat: Outdated water management

#8: Kobuk River – Alaska

Threat: Road construction

#9 Tijuana River – California, Mexico

Threat: Pollution

#10: Blackwater River – West Virginia

Threat: Highway development

For Women’s History Month, Katie Schmidt, Associate Director of the National Dam Removal Program at American Rivers, reflected on what motivates her to continue advocating for healthy, free-flowing rivers nationwide.

I want my grandchildren’s grandchildren to be able to enjoy clean, free-flowing rivers. I want a world where they hear the birds sing, see fish swimming in the rivers, and enjoy the blooms of spring and the vibrant colors of fall. I want clean air for them to breathe and clean water for them to drink.

As a whitewater paddler, I have developed a deep connection to rivers and a desire to protect them. Rivers are my happy place, where I feel most alive, most joyous, and I want that experience to be available in the world our children inherit.

I was seven months pregnant when I first was on Capitol Hill. When I discussed the need for protecting rivers and access to clean water, I had a built-in “talking point” that this work was important not only for people today, but for the future. Last month my family joined me on a trip to Washington, D.C. for our annual lobby days. In between my meetings and their museum visits I took them to the Capitol Building. Even though they don’t understand what all I do yet, they know I go to Capitol Hill to “talk to people about rivers.”

In my role at American Rivers, I get to work with partners across the country who are restoring rivers by removing dams. For the past several months, I have been leading webinars for our community of practice and they each start with, “Welcome, I am excited that you are here,” and I am. We cannot do this work alone; we must work together to restore rivers and protect them from future harm.

My mother and my grandmothers instilled in me a sense of wonder and respect for the natural world. I still carry forward one of the lessons from my grandmother who would always tell me, “Don’t pick the wildflowers. If everyone picked them, there wouldn’t be any flowers left to enjoy.”

When I became a mother, working to protect the environment was no longer a choice – it became a necessity. My two boys are my north star, my source of hope and direction even as we experience the impacts of climate change. For them, and for the children of generations to come, I am working to restore rivers.

What motivates you? Tell us in the comments!

President Joe Biden on Saturday signed a $460 billion package of spending bills approved by the Senate in time to avoid a shutdown of many key federal agencies including EPA, NPS, NOAA, and DOI. The legislation’s success is met with mixed reactions as cuts to key programs will make it more difficult for agencies to improve river health and fully address climate change.

President Biden signed a budget package for water, environment, and energy agencies that includes earmarks for water projects and an EPA spending cut. Across 64 river health programs, less than half of the programs maintain level funding and a majority will see budget cuts under the final appropriations agreement for Fiscal Year 2024. This package while holding the federal government’s overall discretionary budget to roughly the same as last year means some river programs will see a cut due to the raise of inflation and other costs that are unaccounted for total spending.

Last year, the Fiscal Year 2024 River Budget recommended federal priorities for agencies, including the Department of Interior, Department of Agriculture, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and Environmental Protection Agency, to promote climate-smart agriculture practices, improve water infrastructure, restore watersheds, modernize flood management, and support dam removal and rehabilitation. The River Budget spotlighted needs in five key categories including promoting climate-smart agriculture, restoring watersheds, modernizing flood management, improving water infrastructure, and rehabilitating dams.

The partial budget package, signed into law, will place a focus on Western water infrastructure with modest increases to the Klamath Project ($47M), Lower Colorado River Operations Program ($49M), and the Central Valley Restoration Fund ($46M). As populations in the West grow and water supply shrink due to drought, this could not come at a better time but more needs to be done. The package does fund EPA’s geographic programs at the same level as last year, which is good but not great because costs due to inflation impacts agencies as they do companies and people. This package will ensure that we continue to address climate change and protect federal lands and endangered species while maintaining current staffing levels at national parks, wildlife refuges and more.

Below are a few other highlights from the FY24 Senate and House appropriation bills:

| Agency | Program | FY 24 Rec. From | Minibus 3/6/26 | About the Program |

| Army Corps | Engineering with Nature | $20M | $10.5M | Aligns natural and engineering processes to deliver economic, environmental, and social benefits |

| Environmental Protection Agency | Chesapeake Bay Program | $93M | $92M | Restores and protects water quality and ecological integrity in the Chesapeake Bay |

| National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund | $65M | $65M | Protects, restores, and conserves Pacific salmon and steelhead |

| Bureau of Land Management | Wild and Scenic Rivers | $7.5M | Not referenced, but committee says agency will receive funding | Preserves rivers with outstanding natural, cultural, and recreational values |

| Bureau of Reclamation | Klamath Project | $35M | $46.6M | Provides funding to improve water supplies in the Klamath River Basin |

| National Parks Service | Partnership for Wild and Scenic Rivers Program | $5.5M | $5.3M | Protects outstanding rivers and river-related resources through a collaborative approach |

| U.S. Fish and Wildlife | National Fish Passage Program | $30M | $15M | Restores rivers and conserves aquatic resources by removing or bypassing barriers |

| Forest Service | Legacy Roads and Trails Program | $100M | $6M | Stormproofs stream crossings and fixes culverts that are necessary for fish passage in national forests |

*For a full update on river programs, see here.

While not perfect, we will urge our lawmakers to move forward with bipartisan solutions to deliver the necessary funding for river health programs in FY25 and beyond. We thank Senator Murray (D-WA), Senator Collins (R-ME), Congresswoman Kay Granger (R-TX), and Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) for working toward a bipartisan solution that meets the needs of people and rivers. Their leadership is instrumental in protecting our communities and giving rivers a fighting chance to bounce back. We understand tough choices must be made for us to find compromise and make progress on priorities.

Unfortunately, the approps package does have its drawbacks. It rejects hiring staff to work with producers and rural communities, chips away at EPA’s environmental justice programs, and makes us more dependent on oil and gas production. Reduced funding will only set rivers back. And while the Army Corps sees a boost in funding (an increase of $21 million), fewer funds are directed to flood and storm damage reduction. Additionally, the Fish and Wildlife Service will receive a $51 million cut and the National Park Service will receive a $150 million cut. However, the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration gets a near 8% increase to its climate programs. At the end of the day, less funding means greater risks to communities and rivers when pollution standards are watered down, projects get canceled or delayed, and rulemakings cannot be started, finalized, and effectively implemented because of cost constraints or the inability for agencies to get the capacity they need to succeed.

This week, the Biden Administration announced the President’s Budget for Fiscal Year 2025, a set of federal agency priorities and funding requests. With the Fiscal Year 2025 discussions underway, stay tuned about how we can work together and put pressure on Congress and the Administration to support robust funding for our priorities and uphold our community’s topline recommendations in the River Budget for FY25.

In her anthology Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry, writer and editor Camille T. Dungy sheds a light on nature writing by African American poets; a genre that has not commonly been counted as one in which African American poets have participated. She has noted, “Because of erasures from so many narratives about the great outdoors, the idea that Black people can write out of a personal relationship to nature and have done so since before this nation’s founding comes as a shock to many people.” I’m excited to share the work of “water writers” as I call them, from the Black literary tradition, and illuminate connections between nature and culture. As a multidisciplinary artist and writer myself, I am passionate about telling river and water stories through the genre of nature writing and sharing the works of writers who have influenced me.

Many are familiar with Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes, and may know his poem, The Negro Speaks of Rivers, first published in 1921. Hughes writes of the Mississippi’s “muddy bosom” turning “all golden in the sunset.”

Hughes juxtaposes the Mississippi’s description with regal and ceremonial images and action, including, bathing in the Euphrates, building near the Congo, and looking upon the Nile and her pyramids. This poem elevates and conjures an ancient African regality for the Gulf South’s Mississippi River, and African Americans gazing upon her.

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Hughes begins and ends with, “My soul has grown deep like the rivers.” Mother Mississippi is where my soul grows deep too.

Next, I’m thrilled to highlight the work of the 19th Poet Laureate of the United States (2012-2014), Natasha Trethewey. Like me, she yields from the Gulf Coast and writes about race and relationship through narratives of the river and natural world. Her poem Elegy [“I think by now the river must be thick”] is an elegy for her father, and summons memories of casting and catching. She writes:

All day I kept turning to watch you, how

first you mimed our guide’s casting

then cast your invisible line, slicing the sky

between us; and later, rod in hand, how

The invisible line between them, a color line, becomes invisible as she writes in metaphor about fishing and fathers; a nature writer who invokes cultural and social forces through “water writing.”

Finally, I’ll frame author, anthropologist, and filmmaker Zora Neale Hurston’s work as “water writing.” In Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo, Hurston shares the story of Kossula “Cudjo” Lewis and his community, located where the Mobile River meets the bay, in Plateau, Alabama in 1927.

Hurston relates Kossula’s firsthand account as a survivor of the Clotilda and the community of formerly enslaved Africans said to have been the cargo of this “last slave ship.” In one of her most significant vignettes, Hurston visits this community, situated at the confluence of the Mobile River and Chickasaw Creek, at the mouth of the Bay on a sweltering hot day. Her interview includes the heat and thirst in the cabin, she writes of Kossula’s thirst:

I waited but not a sound. Presently he turned to the man sitting inside the house and said, “Go fetchee me some cool water.” The man took the pail and went down the path between the rows of pole-beans to the well in the daughter-in-law’s yard. He returned and Kossula gulped down a healthy cup-full from a home-made tin cup.

Hurston captured the importance of “cool water” in this passage, allowing readers to experience the swelter, the rustle of pole beans, the metallic clink of the pail, and the relief of the cool water fetched. These cool waters are the site of baptisms in the community, and today, are the sacred waters embracing the remains of the Clotilda.

My hope is that everyone who loves rivers will recognize their cultural significance and celebrate the Black Literary tradition’s nature writing authors. Let us hear the river and water stories of African American writers that claim rivers as spaces of conflict as well as celebration.

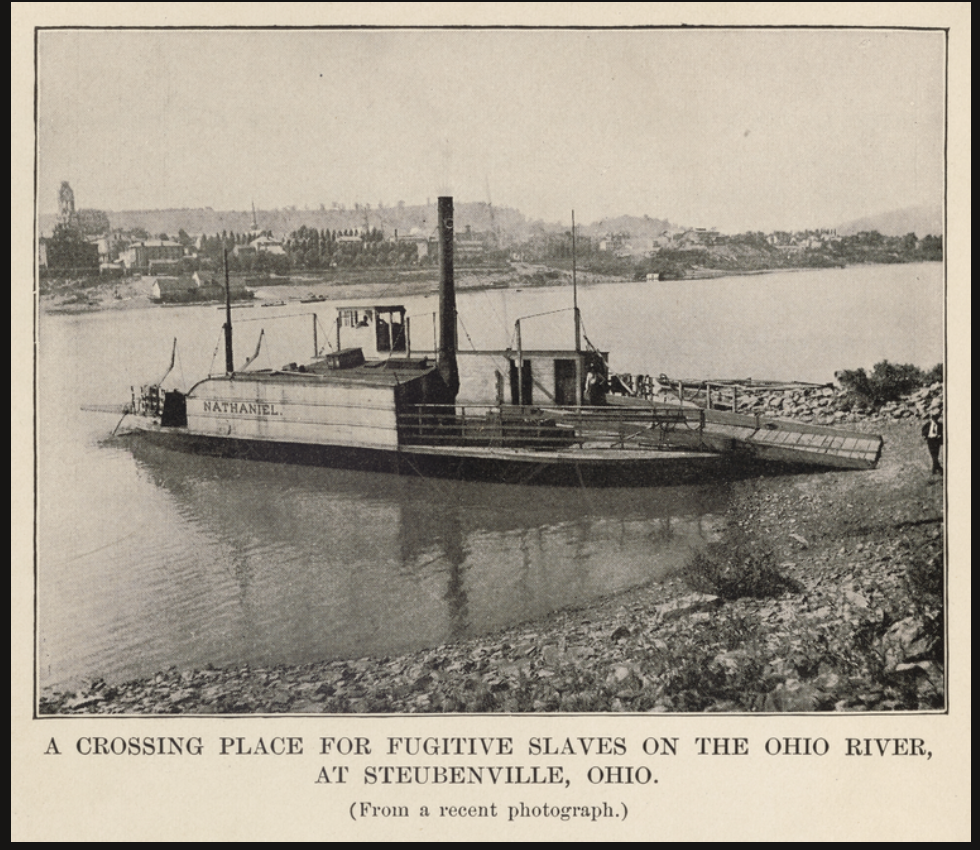

Rivers have been sites of trafficking as well as sites of crossing and emancipation. Rivers have been the sites of lynching and drowning as well as sites of baptism and jubilation.

In his poem, Gwendolyn Brooks: America in the Wintertime, Black Arts Movement poet, author, publisher, and educator Haki R. Madhubuti writes:

you have fought and fought most of the twentieth century

creating an army of poets who learned

and loved language and stories

of complicated rivers, seas, and oceans.

May we all speak the love language of the water writers and commit ourselves to the cause of healthy rivers and clean water for people and nature.

When it comes to wild rivers, Idaho is among the richest within the lower 48 states. But the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest is about to abandon protections for some of the state’s most cherished free-flowing gems.

The Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest is neither the pan nor the handle of Idaho; it’s in between. This area boasts the headwaters of the Lochsa, Selway, and Salmon rivers, renowned for their big whitewater and multi-day river trips. The Clearwater River’s middle, north, and south forks are well-known angling destinations for steelhead, westslope cutthroat trout, and bull trout. These are the streams where endangered fish will return following the eventual removal of the Lower Snake River dams between Lewiston, Idaho and Tri-Cities, Washington. Scientists have referred to Nez Perce-Clearwater country as the Noah’s Ark for salmon because its higher-elevation rivers will remain cold enough to sustain healthy fish populations even as climate change worsens.

In 2021, the Biden Administration established a goal to conserve at least 30 percent of U.S. lands and freshwater by 2030, an initiative commonly referred to as America the Beautiful. It is the job of public land management agencies, including the U.S. Forest Service, to meet the administration’s climate goal by inventorying and applying protections to deserving lands and inland waters.

Granting long-term administrative protections to Wild and Scenic eligible and suitable rivers is one of the most effective ways to make them more resilient in the face of climate change. The Forest Service’s science points to the importance of protecting climate refugia – rivers are anticipated to remain cold enough by 2040 to support coldwater fish species. With only a fraction of rivers having any type of protected status, the administration is far from meeting its America the Beautiful goals, meaning that contributions by every national forest count.

Other nearby national forests in Idaho and Montana are playing their part. Since 2015, five forests have revised their land management plans and collectively more than doubled the number of rivers protected and increased protected river miles by more than 75 percent.

Sadly, the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest is eliminating protections for 86 percent of its Wild and Scenic eligible rivers in its new forest plan. Across four million acres of inland rainforest, the Forest is offering up just 12 streams to support the administration’s broad-reaching climate goals. Since forest plans typically last for decades, the detrimental decisions made now by the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest will adversely affect rivers and fish for generations.

In all, the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest’s new forest plan would remove protections from nearly 700 stream miles. Among the waterways that would lose protections are tributaries to the Lochsa River and the North and South Forks of the Clearwater River. The North Fork Clearwater River, which has been protected for more than 30 years, provides nearly 80 contiguous boatable miles and unsurpassed habitat for bull trout and westslope cutthroat trout. The South Fork Clearwater River is renowned for its unmatched B-run steelhead fishing, miles of walk-and-wade shoreline, and robust whitewater. The Forest is also arbitrarily abandoning protections for:

- 72 percent of streams that have been protected since 1990

- 80 percent of streams anticipated to provide future climate refuge for threatened and endangered coldwater fish

- 70 percent of streams that have cultural significance to the Nez Perce Tribe, including the Bear Creek Salmon Hole

- Streams with superlative scenery and recreational values such as the longest waterfall at 300 vertical feet, the best place to view spawning salmon, and the most popular natural hot springs found on the Forest

The Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest is stripping protections from these special rivers based on false assumptions that Wild and Scenic River eligibility and suitability will hamstring forest management and endangered species recovery. Wild and Scenic protections prevent wholesale commercial logging and clearcutting within designated corridors, but allow vegetation management, wildfire mitigation, habitat restoration projects, motorized travel on existing roads and trails, and other activities, as long as they don’t diminish river values. In fact, well-planned projects can enhance river protections.

If adopted as written, the revised Nez Perce-Clearwater Forest Plan will not only violate the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and agency planning policy, but it would also undermine President Biden’s Climate Policy. American Rivers is asking Forest Service leadership to correct the egregious errors in the new forest plan to ensure that we protect the best rivers and streams we have today for future generations.

Join other river advocates: Tell the Forest Service to uphold protections for Idaho’s rivers.

Climate change is playing out right before our eyes and as the planet warms, storms will increase in intensity and severity followed by longer periods of drought. These are not insurmountable problems – this is a design and systems issue that proactive investments in climate resilience would address.

In December 2023, another atmospheric river hit northern Washington and Oregon causing major flooding including the highest levels ever recorded in the Stillaguamish River.

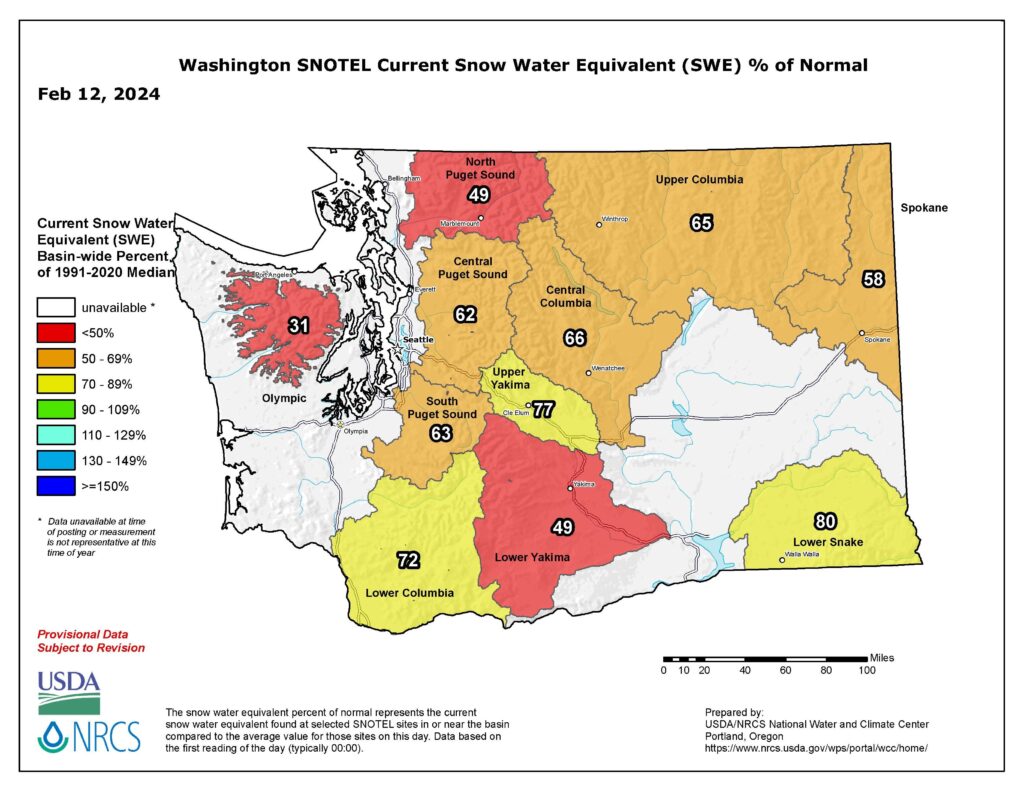

However, much of this precipitation fell on the west side of the Cascades and did not help the drought-starved eastern side of the states – where most of our food is produced.

The long narrow bands of warm water vapor that make up atmospheric rivers extend far out into the Pacific Ocean and carry vast amounts of water. A strong atmospheric river can transport 7.5-15 times the average flow of water at the mouth of the Mississippi River. Similar atmospheric rivers were responsible for record rainfall in the Pacific Northwest in November 2021 which caused over $180 million in damages to northwest Washington and billions in British Columbia. In the case of California, a series of atmospheric rivers dropped 30 trillion gallons of water on the state in 2022 and 2023 resulting in over $30 billion in damages to farmland and infrastructure. An atmospheric river in February, 2024 caused significant flooding and over 475 mudslides in southern California. The damage of which is still being calculated.

While these types of storms are not new, they are becoming increasingly intense and frequent with climate change and intense El Niño weather patterns. With increasing ocean temperatures, warmer air holds more water- resulting in larger storms. These events provide between 30-50% of all precipitation on the West Coast.

Simultaneously, increasing temperatures on land are causing the snow line in many places to increase in elevation resulting in rain instead of snow. While historically metered out over several months of snowmelt, precipitation now comes all at once across a larger drainage basin – contributing to larger floods and prolonged periods of drought.

As stated previously, most of the rain from these storms is trapped on the west side of the Cascade Mountains, contributing little to the desperately needed snowpack in agricultural areas in the Columbia River Basin. In July, 2023 the state of Washington declared a drought emergency for 12 counties due to expected water supply falling 75 percent below normal. Current winter precipitation projections estimate this drought will continue into 2024, causing further undue hardship for water users and the environment.

Communities across the Northwest, and indeed the country, are addressing this in different ways. Indigenous knowledge is being increasingly adopted and communities are developing integrated nature-based solutions to restore floodplains – nature’s sponge.

In their natural condition, floodplains store water, reducing downstream flood damage and recharging groundwater levels while also providing critical habitat for threatened and endangered salmon species.

Washington’s Floodplains by Design (FbD) program promotes the idea of integrated floodplain management that aims to improve the resiliency of floodplains by incentivizing multi-benefit approaches that help make communities and the environment safer, healthier, and more resilient to a rapidly changing climate. This approach looks at the entire river or watershed to understand the different dynamics of flooding, and the diverse needs represented in the floodplain. By working collaboratively across interests, nature-based solutions can be developed to minimize flood risk while also supporting agriculture, salmon restoration, Tribal Treaty rights, and responsible economic development. Not every project can mean a win for every interest, but with strategic vision and benefit-sharing, we can work collaboratively towards a watershed system that will, over time, function better for people, fish, farms, and cities.

During the 2023 global climate conference (COP28) in Dubai, Washington’s FbD partnership was recognized as a leading nature-based approach to climate and community resilience in the face of rising sea levels and increased flood risk. On December 2, The Nature Conservancy’s (TNC) Global Climate Adaptation Director Daniel Morchain, highlighted FbD during a panel discussion emphasizing the need to bring nature-based climate solutions to scale, noting FbD’s collaborative and multi-benefit approach to watershed climate resilience.

FbD was founded by TNC, and currently led by the Washington State Department of Ecology, the Bonneville Environmental Foundation with support from American Rivers. The FbD partnership aims to accelerate integrated efforts to reduce flood risks to communities, and restore fish habitat along Washington’s river corridors. This approach relies on collaboration and engagement from all parties to create long-term solutions and has resulted in reconnecting over 11,374 acres of floodplains, removed or reduced flood risk to 8,482 homes or structures and reduced flood risk for 85 different communities.

Recognition at COP28 comes on the heels of FbD receiving Washington’s Climate Commitment Act funding to advance floodplain management along the Quillayute River- a project that will increase climate resilience for the Quileute Tribe in the face of rising sea levels and riverine flooding.

FbD shows that the impacts of climate change are not insurmountable problems, and it is only by working together across multiple interests that long term solutions can be developed. Increased investment in climate resilient programs like FbD are critical to address the climate crisis.

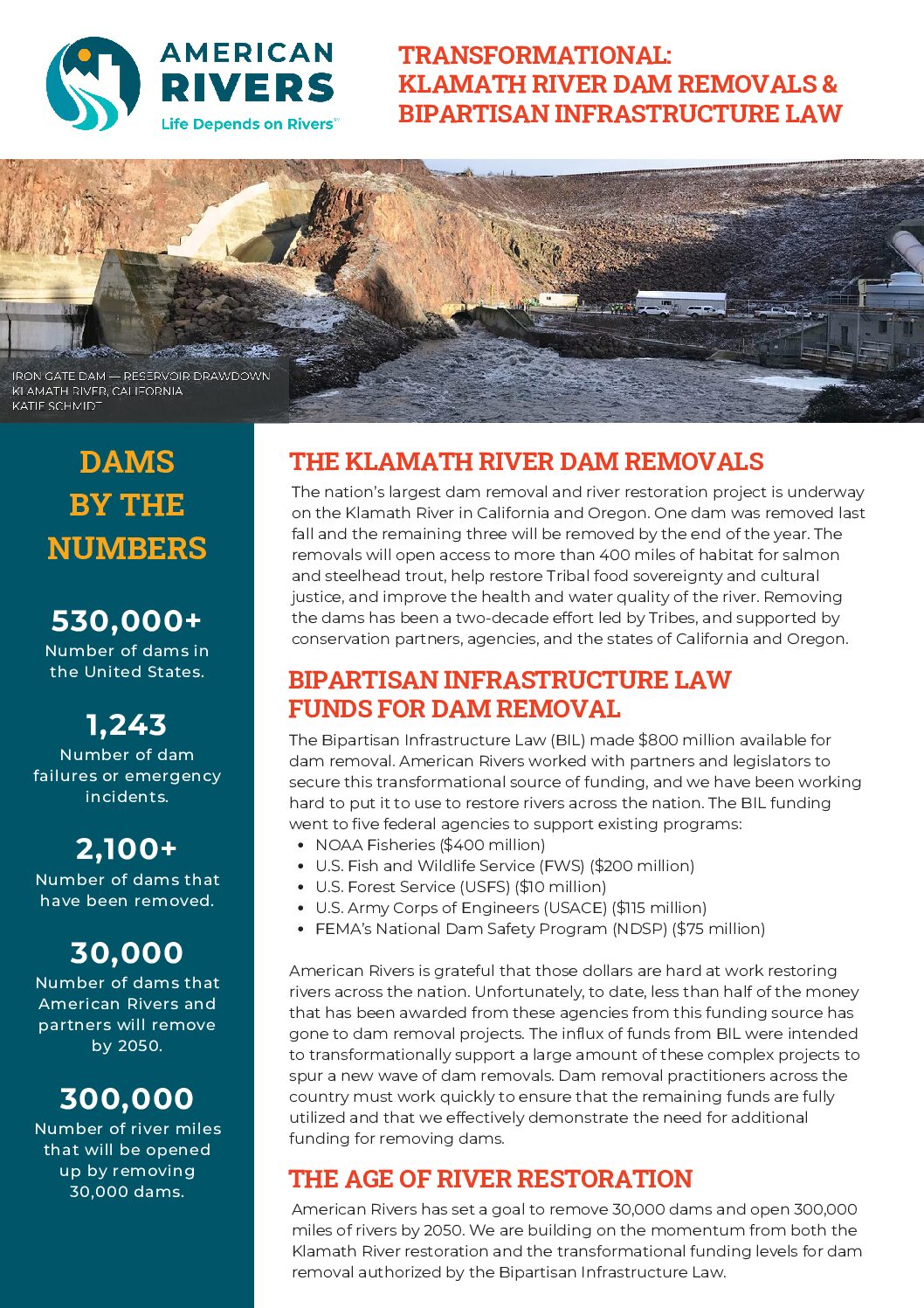

Giddy smiles and stomping feet. We stood next to the Klamath River and watched muddy water rush out from the tunnel under the Iron Gate Dam. The twenty-degree weather couldn’t freeze out the excitement of our group; even as we tried to kick feeling back into our toes, an energy pulsed through us as we watched part of the largest dam removal and river restoration project in history take place.

Our American Rivers dam removal team visited the Klamath River on Thursday, January 11, 2024. This was the first day water was released from the Iron Gate Dam reservoir in preparation for removing the dam. As with every dam removal, there are short term impacts for long term gain. The mud, the sediment: this is normal and expected. This is the river healing itself. And based on the successes we’ve seen with other dam removals – from Oregon’s Sandy River to Washington’s Elwha and White Salmon – we expect the Klamath to come back stronger than ever.

One dam on the Klamath was removed this fall and the remaining three will be removed by the end of the year. The removals will open access to more than 400 miles of habitat for salmon and steelhead trout, help restore Tribal food sovereignty and cultural justice, and improve the health and water quality of the river. Removing the dams has been a decades-long effort instigated by Indigenous grassroots advocates, led by Tribes, and supported by conservation partners, agencies, and the States of California and Oregon.

The Klamath River restoration project sets the bar high and is kickstarting a renewed energy to restore and protect rivers through dam removal across the nation.

American Rivers has set a goal to remove 30,000 dams and open 300,000 miles of rivers by 2050. We are building on the momentum from both the Klamath River restoration and the transformational funding levels for dam removal authorized by the BIL.

I am so grateful and excited to be part of this pivotal moment in river restoration history. Enthusiasm alone does not cut it, however. Though nearly everyone in our country lives within a mile of a river, there is a large gap in the public knowledge on what rivers provide and the importance of restoring and protecting them. I have conversations with folks about this all the time. I have these conversations with members of Congress and their staff, with new partners and dam owners, and sitting on my front porch with friends as we watch our kids run around. Someone asks why I care about dams and I get to share that removing a dam is the fastest way to restore a river.

I want to share a few details of why dam removals are necessary, the benefits provided by these projects, and how we are working together to remove more dams than ever before.

Why Dam Removals are Necessary

More than 530,000 dams block rivers across our country.i Of the 91,843 dams large enough to be included in the National Inventory of Dams, only 19% provide flood risk reduction, 18% provide irrigation or water supply, and 3% provide hydropower.ii Many other dams provide other important services, but these percentages show that many no longer do – possibly more than half of them no longer provide the services they were built to provide decades to centuries ago if you consider the other 440,000 smaller dams that are not in the National Inventory. Too many dams have reached the end of their useful lives and pose public safety risks, negatively impact fish and other aquatic life, and can be costly liabilities to their owners. Countless dams are abandoned, not profitable, or require costly repairs and upgrades that push dam owners to consider removal. Removing dams restores native aquatic life to rivers, increases climate resilience, and reduces the risk of aging dams failing and causing catastrophic flood damages and even loss of human life.

Rivers are dynamic and start to come back to life almost immediately after a dam is removed.iii

Benefits of Removing Dams

- Safety for communities. Dam removal is a permanent dam safety solution. In the last few years alone, dam failures or near failures have forced hundreds of thousands of people to evacuate, caused millions of dollars of property damage, and loss of life.iv In addition, hundreds of drownings have occurred at low-head dams because of the dangerous forces caused by flow hydraulics downstream of the dams.v

- Fisheries, wildlife, and natural heritage. Dams are a major cause of species decline in U.S. rivers, from migratory fish like salmon and herring, nonmigratory fish like trout, and other aquatic species like freshwater mussels. Removing dams is a proven approach to restoring healthy conditions for native river species, with documented results showing increases in fish and other aquatic species populations.vi,vii

- Tribal rights. In a continued effort to more equitably consider Tribal Nations’ water, fishing, and cultural rights, focusing some of these incentives on dam removals where Tribal rights have been infringed allows us to begin to resolve some of these ecological and cultural impacts.

- Jobs. Removing a dam is an intensive infrastructure endeavor providing construction, engineering, scientific, planning, and other jobs. Dam removal projects support 12 to 15 jobs per $1 million invested.viii

- Climate resilience for rivers. Free flowing rivers that are connected to their floodplains are better able withstand the impacts of climate change by limiting and controlling flooding.ix Because free-flowing rivers do not produce methane, and ponded water does, some dam removals can also reduce potential sources of greenhouse gases.x,xi

Removing 30,000 Dams by 2050

American Rivers set a goal working with our partners to remove 30,000 dams and open 300,000 river miles by 2050. More than 2,000 dams have been removed in the country so far, and we want to increase that by a factor of ten. The transformational funds provided by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law are helping to meet the momentum of the moment brought on by removing the four dams from the Klamath River.

Why 30,000 dams? I wondered the same thing, at first. The more that the number has sat with me, the more that it makes sense. When you consider that there are more than 530,000 dams in our country, removing 30,000 dams is completely reasonable (less than 6%). If we really want to restore habitat connectivity and water quality and habitat in a meaningful way, we need to remove a lot more dams.

Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Funds for Dam Removal

With the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), $800 million was made available for dam removal. American Rivers worked with partners and legislators to secure this transformational source of funding and we have been working hard to put it to use to restore rivers across the nation. The BIL funding went to five federal agencies to support existing programs:

- NOAA Fisheries ($400 million)

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) ($200 million)

- U.S. Forest Service (USFS) ($10 million)

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) ($115 million)

- FEMA’s National Dam Safety Program (NDSP) ($75 million)

Two years since the bill passed, 89 dam removals have been funded.xii,xiii American Rivers would like to thank each agency for their work to distribute and manage this funding and for their support of dam removal projects. We are grateful that those dollars are hard at work restoring rivers across the nation.

Unfortunately, to date, less than half of the money that has been awarded from these agencies from this funding source has gone to dam removal projects. We have worked with the heads of agencies, regional staff, and partners to address this, yet we continue to see the funds go to more shovel-ready and short-term projects for fish passage. Dam removals are generally large projects that require a lot of funding and several years of work to see the project through from inception to the physical removal of the barrier. The influx of funds from BIL were intended to transformationally support a large amount of these complex projects to spur a new wave of dam removals.

NOAA Fisheries, FWS, and USFS have until 2026 to utilize the allocated funds. With only a few years left, American Rivers and dam removal practitioners across the country must work quickly to ensure that the remaining funds are fully utilized and that we effectively demonstrate the need for additional funding for removing dams.

Dam Removal Projects Across the Nation

American Rivers is grateful for the work achieved thus far, and we need to keep working with partners, agencies, and dam owners to continue this good work. Below are five ongoing projects that demonstrate the need for these resources.

- Cypress Branch Dam, Cypress Branch, Maryland

– Located in the Lower Chesapeake Bay Basin, the dam serves no purpose and is in an advanced state of disrepair. American Rivers is working with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on this project and is seeking funding through the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Covington Millpond Dam and Drakes Millpond Dam, Cottingham Creek and Three Creeks, South Carolina

– Located in the Lower Pee Dee Basin, these two dams were breached by Hurricane Florence and continue to prevent aquatic organism passage. Both dam owners are engaged in the process and American Rivers is seeking funding from NOAA Community-based Restoration Program. Removal of these dams would reduce flood risk to downstream communities and infrastructure, and also restore natural flows to approximately 100 square miles.

- Powell Dam and Junction Falls, Kinnickinnic River, Wisconsin

– Located in the Lower St. Croix River Basin, Junction Falls produces 1% of energy needs for the community and Powell Dam was decommissioned in 2022. The owner of the dams, City of River Falls, has resolved to remove both dams as part of a major river restoration plan. The dam owners are working with the Kinni Corridor Collaborative and are seeking funding from USACE, programs funded by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and other public and private funding sources.

- Scott Dam and Cape Horn Dam, Eel River, California

– Located in the Upper Eel River Basin, these potential dam removals would make the Eel River California’s longest free flowing waterway. Federal funding is critical to support restoration of the Eel River watershed after PG&E has removed its in-water facilities. California Trout, Trout Unlimited, and American Rivers are working with a broad coalition to support dam removal.

- Lake Jefferson Dam, East Branch Callicoon Creek, New York

– Located in the Upper Delaware River Basin, this is an unsafe and uneconomical high hazard potential dam that is nearly a century old and has no fish passage. The dam owners are fully committed to removal and have sought assistance from American Rivers and FWS to remove the dam. American Rivers is seeking funding through NOAA Community-based Restoration Program, FWS, and additional sources.

The Age of River Restoration

Twenty-five years ago, people just like me sat on the banks of the Kennebec River, listening to the bells toll from downtown Augusta, Maine as the first notch came out of the Edwards Dam. That day launched a movement to remove dams across the country and restore the rivers on which they were built and over 1,800 dams have come out since then.xiv

The dam removals and river restoration on the Klamath River in Oregon and California is an opportunity to kickstart a new wave of dam removals at an unprecedented level. The BIL funding is a down payment and we will all need to work together to secure funding and support for restoring rivers for generations to come.

Removing a dam is the fastest way to restore a river back to life and free-flowing rivers are critical to support biodiversity and climate change adaptation. Life depends on rivers and rivers depend on us to remove dams.

I am hopeful for our future, and for future generations, that we can look back on this moment and know that we are working to restore rivers for the benefit of all.

For additional information on the National Dam Removal Community of Practice and our webinars on dam removal, please see www.americanrivers.org/DamRemovalCOP

[i] Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership, National Aquatic Barrier Inventory and Prioritization Tool, www.aquaticbarriers.org

[ii] U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, National Inventory of Dams, https://nid.sec.usace.army.mil/#/

[iii] O’Connor, J.E., J. J. Duda, and G. E. Grant. (2015). 1000 dams down and counting: Dam removals are reconnecting rivers in the United States. Science 348(6234), 496-497. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa9204

[iv] Association of State Dam Safety Officials, Dam Incident Database Search, https://damsafety.org/Incidents

[v] American Society of Civil Engineers, National Inventory of Low Head Dams, https://www.asce.org/communities/institutes-and-technical-groups/environmental-and-water-resources-institute/national-inventory-of-low-head-dams

[vi] NOAA Fisheries, Successful Fish Passage Efforts Across the Nation, https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/insight/successful-fish-passage-efforts-across-nation

[vii] McCombs, Erin, Dam removal and freshwater mussels: effective restoration and prioritization through case studies, https://scholarworks.umass.edu/fishpassage_conference/2014/June10/46

[viii] Value of Water Campaign, The Economic Benefits of Investing in Water Infrastructure, https://thevalueofwater.org/media/new-analysis-finds-closing-investment-gap-water-infrastructure-would-create-13-million-jobs

[ix] Ganey, S. and L.Spurrier, PEW, 8 Benefits of Healthy, Free-Flowing Rivers, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2022/09/22/8-benefits-of-healthy-free-flowing-rivers

[x] Environmental Protection Agency, Research on Emissions from U.S. Reservoirs, https://www.epa.gov/air-research/research-emissions-us-reservoirs

[xi] Levasseur, A. et al. (2021). Improving the Accuracy of Electricity Carbon Footprint: Estimation of Hydroelectric Reservoir Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 136 (2021) 110433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110433

[xii] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fish Passage Portal, https://interagency-bil-fish-passage-project-1-fws.hub.arcgis.com/

[xiii] American Rivers is internally tracking and has found 89 dams are funded for removal

[xiv] American Rivers, Dam Removal Database, https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/American_Rivers_Dam_Removal_Database/5234068

[xviii] Association of State Dam Safety Officials, Dam Incident Database Search, https://damsafety.org/Incidents [1] American Rivers, Dam Removal Database, https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/American_Rivers_Dam_Removal_Database/5234068

Guest blog for the Southwest River Protection Program by Mike DeHoff, Returning Rapids Project

Recently I found myself looking up the definitions for “cubic feet per second” and “acre feet.”

Cubic Feet Per Second (cfs) – a means to measure water in motion.

Acre Foot (af) – a means to measure impounded water.

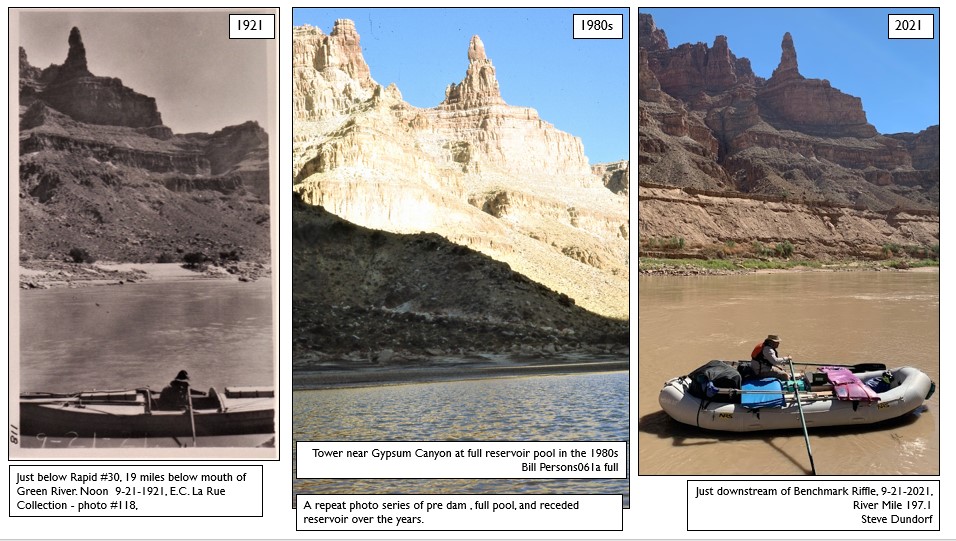

When Lake Powell reservoir behind Glen Canyon Dam was full or nearly full in the 1980s and 90s, both means of water measurement could be found in Cataract Canyon. In the heart of Canyonlands National Park, Cataract Canyon starts where the Green River and Colorado River come together in a craggy and uniquely sublime landscape where sun, sandstone, and ravens dominate the 2,000-foot-deep canyon system. This 41-mile stretch of river corridor is the furthest upstream section of the Colorado River that was affected by Glen Canyon Dam’s impoundment of river water.

Much like other western spaces, the boundary between river and reservoir was drawn with manifest destiny in mind. Elevation was used to create this boundary, drawing a topographic line from the massive concrete dam structure that sits 186 river miles downstream from the heart of Cataract Canyon. Three thousand seven hundred and twenty feet above sea level designates a man-made water storage basin for the reservoir known as Lake Powell.

Anyone who traveled through Cataract Canyon in the last two decades of the 20th century would have encountered both cubic feet per second and acre-feet: Cubic feet per second as a flowing living river for the first 40% of Cataract where boaters were greeted with a symphony of successive rapids. Then the river would slow down and the water’s character would change – not only in color as the river dropped its sediment but also in definition. In the heart of Cataract Canyon, you had to travel across miles of impounded water – many thousands of acre-feet of impounded water – until the canyon walls finally permitted a place where a road met the flooded river corridor and you could take your boat out of the water.

Over the last 20 years, this has changed. Cataract Canyon has seen a fascinating transformation as Lake Powell reservoir has receded in the face of climate change and overallocation. Now, even though the reservoir has left an impact, acre feet cannot be found in Cataract Canyon. Now it is all flow. With the full shift to cubic feet per second – to water in motion – ecologic characteristics that only a flowing river can bring have returned. Native plants and animals are thriving again in a now healthier high plateau desert canyon.

The reservoir, the dam, and its acre-feet of impounded water still persist downstream. Nature is challenging this engineered boundary allowing Cataract Canyon to be the last wild – non-engineered – section of the Colorado River. Downstream in Glen Canyon is where the Colorado does shift from its wild cubic foot per second self into being a commodity that is separated, distilled, stored, and used by millions of people for personal and economic benefit.

For anyone who finds rivers fascinating, Cataract Canyon is now one of the finest open-air river laboratories in North America. The Colorado River gathers a healthy sediment load as it flows from its mountainous source and into the expansive Colorado Plateau. When Lake Powell reservoir was full and the waters shifted from cubic feet per second to acre-feet in lower Cataract Canyon – all the sediment load carried by the river was dropped out of suspension and into the submerged river corridor. That sediment buried rapids, cultural and historic sites, side canyons, and a fascinating geologic record that was displayed in a deep canyon.

The natural processes that coincide with cubic feet per second are now at work remobilizing the sediment that was left behind as Lake Powell reservoir retreated from Cataract Canyon. Rapids that were covered with mud – the byproduct of impounding the Colorado into acre feet – are being carved back out. The river is reclaiming its gradient as Lake Powell shrinks to one-third of its former self. Where once there was the silence of still water, there is now the purring of eddy currents, burbles of boulders rerouting the current, and as of Fall 2023, 10 rapids have been carved back out of the mud.

When impounded water was contained in lower Cataract Canyon, the annual fluctuation of the reservoir level scrubbed the canyon walls of any vegetation. Thanks to flowing water, now there are willows, cottonwoods, and other native plants populating the river banks as they have out-competed invasives. Side canyons are scouring out the reservoir-deposited sediment and similar riparian recovery can be seen there as well. This speedy large-scale ecological repossession is incredible to observe and brings many questions to mind. Will the reservoir ever be so full that it inundates Cataract Canyon again? How do we manage this river corridor for the future? What resources do we prioritize over others?

This is just one capsule exemplifying bigger dilemmas we now face in the Southwest. While acre-feet of water may enable the quenching of economic thirsts in the region, it is a river flowing with cubic feet per second that will continue to bring life to the canyons and river corridors we revere. Mike DeHoff lives near the Colorado River in Moab, Utah, and is part of the Returning Rapids Project research team. Visit the Project’s webpage for a detailed dive into the returning rapids of Cataract Canyon, as well as photo matches, maps, data, preliminary findings, and a portal to donate.

University of Montana wildlife biology student Jaydon Green traveled throughout western Montana this fall photographing rivers for American Rivers through the eyes of both an artist and a scientist. He shares with us his experiences of learning to capture the essence of wild rivers.

These are just a few of the 28 special rivers flowing within the Lolo National Forest that deserve protections to ensure they remain clear, cold, and copious well into the future. Interning with American Rivers allows me to share the beauty of wild rivers with you.

Rattlesnake Creek

Growing up, I spent a lot of time walking around outside looking for bugs, birds, and other little critters I could see in my neighborhood. This quickly developed into a passion for exploring and discovering animals and plants that can’t be seen in everyday city life. When I moved to Missoula, one of the first things I noticed, and soon fell in love with, was how interconnected the city is to nearby nature. Rattlesnake Creek is somewhere I often return. The sounds of the creek, the rustling leaves, the call of a bird- evoke a sense of inner calm. I feel like a kid again. Chasing the pileated woodpeckers from tree to tree. Watching the deer seamlessly navigate the twists and turns of the intricate forest floor. I always find something I haven’t seen before, and my childhood self couldn’t be happier.

Fish Creek

I arrived at the North Fork Fish Creek Trailhead before first light and took one of the freshest breaths of air I have ever inhaled. The air was cool and crisp, and the ground was covered in dew. A thick surreal fog had settled in the valley. In the dawn light, tears of joy came to my eyes when walking through a previously burnt forest, as I saw thousands of young trees growing and bringing back life. As I walked down this trail taking pictures and exploring, I lost track of time.

Thompson Falls

As a wildlife biologist, I find comfort in the natural world, where the land appears untouched and the waterways create their own paths. I remain stubborn in believing that development could never amaze me in the same way that patterns in the bark on a tree do. When visiting the Thompson River and nearby Thompson Falls Dam, I was shocked by the contrasting dynamic between natural and man-made.

Clearwater River

Seeley Lake’s symbiotic relationship with the Clearwater River is unmistakable. Beyond providing a stunning backdrop, the river serves as a lifeline for Seeley, offering recreational opportunities, sustaining wildlife, and fostering a sense of community. The river, much like area residents, adapts and flows, embodying the resilient spirit of this close-knit community. I was approached by several locals who asked why I was taking photographs. This led to rich conversations with people who share a deep love and connection to this river. The Clearwater River isn’t just some river; it’s a character in Seeley Lake’s story. When photographing this area, I sought to capture the way the town embraces the river, and the river, in turn, is part of Seeley Lake’s identity.

further Resources

Learn how rivers stir our creative juices

Learn more about why Western Montana rivers deserve new protections

Learn more about the American Rivers Northern Rockies office and our work to protect rivers in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming

When I first set foot in the Klamath watershed as a scientist back in 2008, dam removal seemed little more than a dream. An official decision had not yet been made by the Department of the Interior about whether dam removal was in the best interest of the Klamath basin, including its people, while salmon populations had declined to the point where the Secretary of Commerce closed West Coast commercial salmon fishing. Large-scale restoration projects were discussed as “possibilities,” but were by no means certain. And, though the ecological outcome of years of adverse land and water use practices was clear, the National Research Council reaffirmed in a report released that year that we lacked a “big picture” understanding of the Klamath River and its ecosystems.

Fast forward 15 years and I’m on the edge of my seat as three dams on the Klamath River see their final days, with a fourth already removed. How did we arrive at this historic juncture? How does a river that boasted the second-largest salmon population in California become constricted and sickly over the course of a century, and how did we progress from catastrophic fish kills to restoration and the climax of the world’s largest dam removal project?

There is no neat beginning, but the story behind the Klamath dam removals is deeply tied to people of the watershed, a narrative that stretches back to time immemorial. The Hoopa, Karuk, Klamath, Modoc, Yurok Tribes, and others stewarded the landscape and thrived along the Klamath and its tributaries, with the river constituting a core element of daily life, ritual, and culture. Prior to the damming of the Klamath River and as late as the 20th century, epic salmon runs were common. But an influx of settlers in the 19th century led to the widespread displacement of the region’s Tribes and the adoption of land and water use practices that negatively impacted the watershed. In the early 20th century, as hydropower became a priority for many of the surrounding communities, construction began on the first of four large hydropower dams totaling 400 vertical feet: Copco No 1 (1918), Copco No 2 (1925), J.C. Boyle (1958), and Iron Gate (1962). While the dams provided modest amounts of power for the surrounding communities, the ecological impacts were severe. By the 21st century, salmon populations, a key indicator of ecological health and an important species in their own right, had fallen to less than 5% of their historical average.

The decline of the Klamath’s health did not go unnoticed by those who call the watershed home, and after a massive fish kill in 2002 that resulted in more than 30,000 dead salmon, momentum began to build towards solutions amongst groups with different interests. Led by the Tribes, a years-long campaign to protect and restore the Klamath followed, with protests at the headquarters of Scottish Power, PacifiCorp, and Berkshire Hathaway to demand removal of the four dams. In 2010, PacifiCorp signed the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement (KHSA) alongside Tribes, counties, state, and federal agencies, but it failed to pass through Congress. Restoration of the Klamath seemed on the ropes until 2016, when PacifiCorp, who owned and operated the four dams, began implementing a revised KHSA that did not require Congressional approval, eventually transferring ownership of the dams over to the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC). While the legal push for removal had cleared a major hurdle, struggles around relicensing continued into 2020. Despite the setbacks, and thanks in large part to Tribal leadership, the efforts of activist groups, and, ultimately, collaboration within the entire Klamath community, Copco No. 2 was removed in the fall of 2023, reconnecting parts of the watershed that hadn’t seen water from the Klamath River in nearly 100 years.

Since joining the Coalition for the Klamath Basin in 2001, American Rivers has worked alongside conservation groups to restore the ecological health, function and native diversity of the Klamath River basin, with an eye to the eventual removal of the dams operated by PacifiCorp. Now we are witnessing the removal of the remaining three dams in real time, simultaneously the largest salmon restoration project in history and the largest dam removal in history. It is a moment to celebrate, and the product of a long and serpentine history. We would be wise to reflect on the legacy of activism and advocacy that brought us to this point, the seemingly insurmountable obstacles and setbacks that had to be overcome, and the bridges that needed to be built to sustain the push towards removal. As we look beyond dam removal, we should recognize that while a freed Klamath River is momentous, there is much work, collaborative work, that needs to be done before the river is healed. This work is already happening. Tribes and private ranchers are working together to restore other parts of the Klamath watershed, ensuring that the knowledge and work of restoration stays within the basin. Dam removal on the Klamath has included work to ensure that drinking water supplies, recreational opportunities, and wildfire readiness are part of the conservation solution. I am proud of the work and commitment people of the Klamath have shown, not just to healing the river, but healing each other.