Tucked away in northern Arizona, sheltered from the generally dire news about water in the West and especially the Colorado River basin, lie the headwaters of the Verde River. The upper section of the Verde River, between Paulden and Clarkdale, along with its critical tributaries Granite and Sycamore creeks, are some of the most ecologically healthy and economically important free-flowing rivers remaining in Arizona.

Local advocates have been working to protect the Upper Verde for over a decade because of its uniquely intact ecosystem and cultural importance. Notably, nearly 15 years ago, the Upper Verde was facing the existential threat of the Big Chino pipeline, a now dormant but not dead groundwater pumping project that would have effectively dewatered the Upper Verde River. But while the river has so far evaded serious development proposals, its flow has certainly been reduced by regional groundwater withdrawal and climate change-driven aridification. And there’s nothing in place to permanently safeguard the river to remain as it is—incredibly wild, undeveloped, and free-flowing.

The Upper Verde has already been found by Prescott National Forest to be both eligible and suitable for Wild and Scenic designation because of its free-flowing status and numerous outstanding values. In a revamped effort to bring permanent protection to this special river through Congressional designation, in late 2021, American Rivers and numerous partners formed the Upper Verde Wild and Scenic River Coalition. Building upon the existing foundation of community support, the coalition over the last two years has made significant progress towards the goal of designating the Upper Verde as Arizona’s next Wild and Scenic River, including introducing the effort to Arizona delegates this past March.

But why the Upper Verde?

The Upper Verde and the campaign to designate it a Wild and Scenic River exemplifies American Rivers Southwest River Protection Program’s goal of protecting our region’s most ecologically and culturally important rivers that remain. Unlike many of our rivers in the Southwest, the Upper Verde is not (yet) in crisis, nor has it been so seriously altered by the consequences of human consumption that it is no longer recognizable. Certainly, the river faces unprecedented threats from climate change, unconstrained groundwater withdrawal, mismanaged recreation, and invasive species. But with the Upper Verde, we have the increasingly rare opportunity to act proactively to protect a wild river. Imagine if we reflected on the consequences of not acting this way for the majority of our waters in the Southwest, but for this river, this time, we made a different choice.

Why Wild and Scenic River designation?

Designation under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act is the highest form of protection for free-flowing rivers in the United States and recognizes rivers of outstanding regional and national significance. The Verde River is the longest free-flowing river remaining in Arizona and holds immense ecological and cultural value, particularly for the Yavapai-Apache Nation. The birthplace of the Verde, the Upper Verde is a crown jewel of the state, providing clean drinking water, exceptional habitat for rare plants and animals, and excellent outdoor recreation opportunities.

The Verde River watershed is only 5.8% of the land area in Arizona, but it contains some of the best remaining riparian areas in our arid region – lush, green riverside habitats that are critical to our wellbeing, to wildlife, and a healthy ecosystem. As a thriving riparian area, the Verde River supports a large fraction of Arizona’s vertebrate species: 78% of breeding bird species, 89% of bat and carnivore species, 83% of native ungulate species and 76% of reptiles and amphibians genera (CWAG, 2022). The Verde River supports 9 of the 22 native fish species protected by the Endangered Species Act in Arizona. The Upper Verde River specifically is some of the best remaining habitat for the Sonora sucker, Desert sucker, Roundtail chub, Spikedace, Razorback sucker, and Loach minnow.

- Recognition as a Wild and Scenic River will:

- Ensure clean water supplies

- Conserve scenery, wildlife, recreation, cultural sites, access to hunting and fishing, and Verde Valley agriculture

- Prevent future large dams and diversions

- Provide more resources for monitoring and management

- Provide opportunities for public engagement

- Assure river access for recreation, hunting, fishing, and traditional uses

- Maintain the river and its remarkable ecosystem as it is for future generations

- Wild and Scenic River status does not:

- Restrict grazing permits

- Alter existing water rights

- Constrain private property rights

Rivers are the lifeblood of Arizona’s desert landscapes, but most have been lost, destroyed, or degraded. Arizona only has two Wild and Scenic Rivers, a lower section of the Verde and Fossil Creek, which constitute less than 1/10th of 1% of the state’s river miles. The Upper Verde remains a refuge for wildlife and nature for people to enjoy and appreciate. Let’s keep it that way!

In June 2023, American Rivers teamed up once again with the Vamos Outdoors Project to float the Wild and Scenic Skagit River. Students from Latine, Migrant, Multilingual, and Newcomer families enjoyed a vibrant afternoon on an ecological gem of a river right in their backyards. We gave the students a few waterproof disposable cameras, and this is what they captured…

A dense, low cloud cover and some morning drizzle stood no chance against nine fired-up high school students. Despite an early Saturday start, the students arrived in Rockport, Washington bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, excited for a day on the Wild and Scenic Skagit River. One student had just graduated high school the night prior and was up celebrating with family until 4 a.m.! When asked about why he wasn’t sleeping in on his first day as a high school graduate, he replied, “I wouldn’t miss this.”

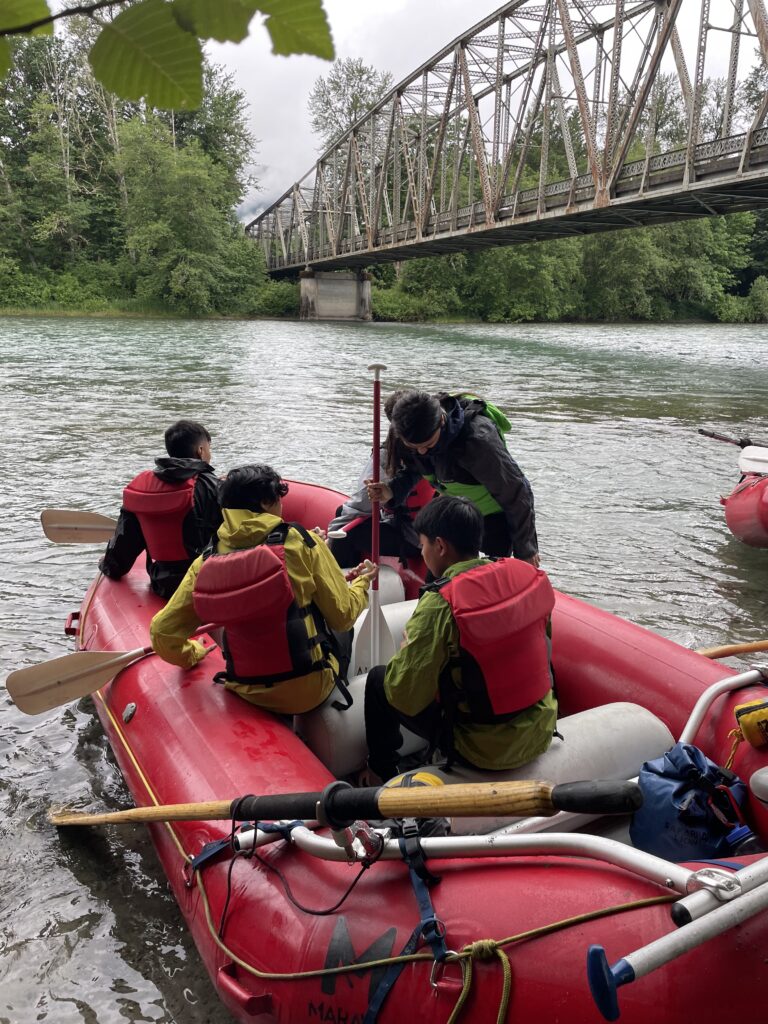

The group set out in two rafts from the Marblemount Boat Launch just off of Highway 20 in eastern Skagit County. The two-boat system quickly gave rise to some friendly competition: which raft team could paddle the fastest, which team could splash the other team the most, and which boat could spot more bald eagles. We floated first past the Cascade River: a cold, clear tributary to the Skagit River which provides excellent habitat for salmon and steelhead spawning and rearing, as well as fantastic whitewater boating opportunities. American Rivers is currently working with partners to designate the Cascade River as an Outstanding Resource Water (ORW) under the Clean Water Act, which would protect the river from activities that might negatively impact its near-pristine water quality. By safeguarding existing water quality, an ORW designation for the Cascade River would help protect clean drinking water for downstream communities, support the local economy, bolster the health and abundance of fish and wildlife species in the Skagit River watershed, and ultimately ensure that the Cascade River will remain as special in the future as it is today.

As we snaked our way through the mid- Skagit’s gentle rapids, the students had a long discussion with our guides about how they got their jobs, and we talked about pathways for students to become outdoor professionals themselves—careers in which several of the students expressed great interest. One of our guides was pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in environmental studies. We talked about the importance of environmental advocacy and opportunities for the students to continue their education if they were interested in environmental protection as a profession. The primary goal of these trips with the Vamos Outdoors Project is for the students to just have fun, which tends to be pretty easy to accomplish given their brilliant attitudes! A secondary goal is to empower the next generation of river advocates. American Rivers recognizes that river protection is perpetual work, and fostering the next generation of river advocates is essential for the longevity of healthy rivers.

The river was clear in most places, allowing for easy salmon spotting. We reviewed the life cycle of Pacific salmon, pointing to places along the river where we might likely see different life stages (e.g., juvenile salmon under low hanging branches for protection, adult salmon along the river’s edges in medium sized gravel appropriate for spawning, etc.). Most students already knew the handy way of recalling the five species of Pacific salmon, which all utilize the Skagit River’s cold, clean water to spawn and rear. The students also got to see areas where the river has eroded banks underneath State Route 20 (AKA the North Cascades Highway), and the 4,430 cubic feet per second pushing our rafts along made the power of water even more evident. In response to this erosion, stakeholders and Tribes in the Skagit River basin have constructed bank stabilization structures like the ones pictured here.

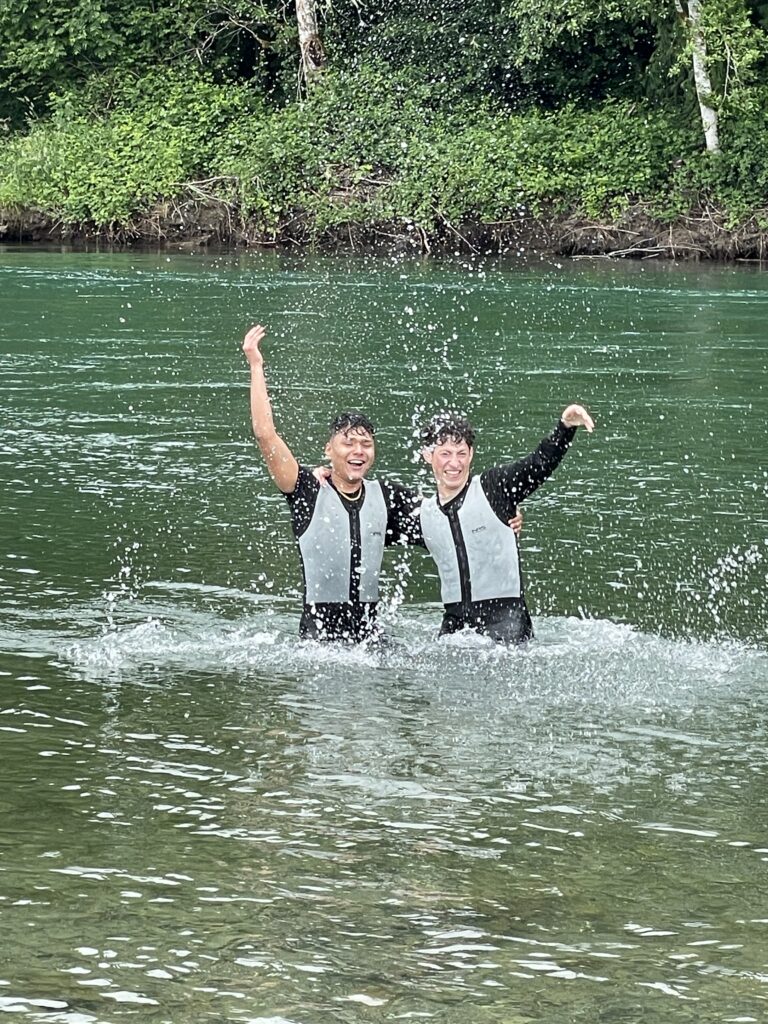

The air temperature was in the low 50s; the water temperature in the upper 40s! The last thing on this American Rivers staffer’s mind was swimming, but the students had other ideas… Our lifeguard-certified guides pulled the rafts over to a sandy bank and every single student ran straight into the water. Hoots and hollers echoed up and down the river. Boats passed by—their operators bundled up in puffy coats and Gore-Tex—watching in awe as the students dunked themselves underwater. The students were fully immersed in the experience—a reminder of all the joy that rivers offer us.

After we hauled the boats out at the takeout, we all gathered for lunch, where we shared our ‘rose, bud, and thorn’ of the trip: something you loved, something that you want to do better, and something that challenged you. Swimming in the river was a very popular ‘rose.’ Many of the students wanted to improve their paddling technique and learn more about whitewater boating, which was a clear signal that we need to continue to offer these opportunities! While the trip leaders thought the weather would present a challenge, not a single student mentioned it. With full hearts (and a warm change of clothes), the students headed back home.

American Rivers is honored to partner with the Vamos Outdoors Project to offer experiences like this to Latine, Migrant, Multilingual, and Newcomer students who have been traditionally underserved in conservation, environmental education, and outdoor pursuits, disconnecting them from their rivers and the environmental threats that disproportionately burden their communities. Listening to laughter carrying over water; seeing smiles big enough to lift heavy clouds; and watching budding river advocates connect with the incredible rivers right in their backyards is truly our ‘rose’ here at American Rivers.

Today marks the 55th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (WSRA) – one of our nation’s landmark conservation laws. Rivers that are designated as Wild and Scenic receive the highest level of protection in the United States – ensuring that future generations can enjoy their free-flowing nature, clean water, and outstandingly remarkable values.

Like many great conservation stories, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act has its roots in Montana.

The Big Dam Era

The 1940s-1970s mark the era of large-scale hydroelectric dam building in the United States. In three short decades, more than seventy thousand dams were constructed along our nation’s waterways – including more than 150 large-scale dams along the Columbia, Colorado, and Missouri river basins. Once wild rivers in the west, they were rapidly being transformed into stair stepped reservoirs and human controlled rivers in order to support agriculture in the arid west and generate electricity to fuel fast growing metropolitan areas. While this feat of human ingenuity drove certain types of prosperity in certain places, it came with significant costs. For the first time in human memory, the Colorado River ran dry before reaching the Gulf of California. Once among the finest salmon fisheries on earth, the Columbia River Basin’s oceangoing fish, along with the Puget Sound Orcas which depend upon healthy salmon runs, faced the very real possibility of extinction. The decision to construct the dams also occurred with little to no consultation with Tribal Nations. No place was too sacred for large-scale hydro development projects – not even within Grand Canyon or Glacier national parks.

An idea is born – the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act

Wildlife biologists John and Frank Craighead came up with the idea for the WSRA while fighting the proposed Spruce Park Dam on the Middle Fork of the Flathead River and the Glacier View Dam, which would have inundated the North Fork Flathead River underneath a massive reservoir inside of Glacier National Park. Although these two projects were defeated, the Craigheads quickly realized natural rivers were becoming scarce, and that stopping one project simply pushed the problem elsewhere. A more systematic approach to river conservation was needed.

In a 1957 issue of Montana Wildlife, John Craighead made the case for protecting the Flathead as well as other rivers nationwide: “Rivers and their watersheds are inseparable, and to maintain wild areas we must preserve the rivers that drain them.”

The Craigheads organized, built community support, and engaged elected leaders from around the nation. With support from Interior Secretary Stewart Udall and senators Lee Metcalf (D-Montana), Frank Church (D-Idaho), and others – the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act passed the U.S. Senate unanimously and was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on October 2, 1968.

Montana & the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act Today

Today, Montana ranks 7th highest in the nation with a total of 408 miles of Wild and Scenic river miles on five segments – the Upper Missouri, the three forks of the Flathead, and East Rosebud Creek. Of Montana’s approximately 169,829 miles of rivers and streams, less than 0.02% have been protected as Wild and Scenic rivers. Since 1976, only 20 miles of one stream, East Rosebud Creek, has received new Wild and Scenic river protections. Meanwhile Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah have added nearly 1,000 miles of new Wild and Scenic rivers since 2009.

The next chapter – the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act

While Montana continues to lag behind our neighboring states in terms of Wild and Scenic river miles protected, the good news is that the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act (MHLA) is our opportunity to write the next chapter in our river conservation legacy.

Introduced by Senator Jon Tester during the last two Congresses, the MHLA would protect 20 streams totaling 385 river miles in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. This includes iconic rivers such as the Yellowstone, Madison, and Smith by designating them as a part of the National Wild and Scenic River System. As Montana’s population continues to boom, the MHLA is our insurance policy to protect these rivers as they are today, for the future generations.

As we celebrate the 55th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, let’s remember that river conservation is ultimately a story about people – folks who cared enough to raise their voices and take action. Will you help us write the next chapter?

Ask Rep. Zinke to support the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act! It only takes 90 seconds to make a difference! Together, we can protect the rivers that flow through our hearts and communities.

Thank you for taking action for Montana’s rivers!

Rivers are the veins and arteries of our world, and they are essential to all life. In the U.S., we depend on our 3.5 million miles of rivers for our drinking water and the food we eat. Rivers provide crucial habitat for fish and wildlife, opportunities for recreation, and spiritual and cultural connections for us, our families, and our communities.

Rivers make life possible, yet we are losing them.

Pollution, dams, habitat destruction, and climate change are harming rivers, fish and wildlife, and our families and communities. Lack of clean drinking water, increasing floods and drought, and species extinction are disproportionately impacting communities of color, Tribal Nations, and people in poverty.

In order to heal our rivers and create the positive, systemic change we need for the long-term, we must unite as a powerful movement with a bold vision for clean water and healthy rivers for all.

As American Rivers celebrates our 50th anniversary this year, we’re looking ahead to the next 50 years. We created this graphic to illustrate the future we are working towards, together with our partners and supporters. Achieving this vision will take all of us.

On this World Rivers Day, we celebrate our rivers and recommit ourselves to the important work ahead.

Susana Sanchez-Young’s illustrations are almost musical: They are catchy, buoyant, and expressive. The East Bay-based mom of two is the founder of The Designing Chica and an art director at the Los Angeles Times. Her clever bilingual plays on pop-culture references are emblazoned on everything from coloring books and paint kits to stickers and wall art. Susana’s art is infectiously happy, and we loved teaming with her to celebrate American Rivers’ 50th anniversary — and the vibrancy of rivers. Find Susana on Instagram @TheDesiginingChica.

We are proud to offer a T-shirt featuring an original design by The Designing Chica for Hispanic Heritage Month, which will help support our longtime partners at the Hispanic Access Foundation.

What inspires your art?

My crazy, cultural upbringing inspires my art and my life. My mother is from Guatemala, my father is from Nicaragua, and I was raised in Hollywood. My parents taught me to love my culture, our music, and speaking Spanish at home. My hard-working mother and aunts and grandmother would take me to clean houses with them after school — houses of movie stars and directors and writers in the Hollywood Hills. There were enormous rooms filled with art and photography, and my job would be to dust and clean out the trash. I would take forever because I loved staring into canvases that were out of this world and taller than me. I would collect all the thrown-out newspapers and magazines, and I would take them home to create collages. I would admire the designed spreads from Vogue before I knew that graphic design and lettering was a career!

Tell us about The Designing Chica. Why did you start it?

When I was pregnant with my first child, I could not find nursery art that represented my bicultural family. I knew chicos and chicas like me wanted representation. At the time I was an art director and designer at the Washington Post, working late hours. I was stressed and tired with a hectic commute, but since I had design and illustration skills, I thought, “Why not create something for myself?” I became my own client! I gave myself more work, but it became therapeutic and fun. I created a type-driven alphabet design that I fell in love with.

Lots of people started asking me to make them custom designs and stationery for their children’s rooms. When my second child turned two, I launched The Designing Chica. Self-funded! I was still working 10-hour days, seeing my kids only in the morning and coming home after a two-hour commute at midnight. I was always exhausted, but excited to create because I had all these ideas percolating in my head. I would stay up late and I sketched and designed postcards with bilingual sayings. It became my passion, and my designs took off!

What inspired you about this project with American Rivers?

I grew up going to Yosemite every summer and spending countless hours in the Merced River. I loved seeing fish swim around my ankles and trying to catch them! I loved collecting and throwing rocks, trying very hard to make each rock skip. I loved bird watching and seeing the birds jump into the water and flutter back out with something to eat in their beaks. I loved staring at the stream over my legs and how the colors would shimmer and change with the reflection from the sun. My siblings and I would splash around and just have a blast for hours. Being in the river as a child was my happy place. As an adult, nothing has changed. You have to pull me away from every river we go to as I can just stay and sit in the water for hours. This piece for American Rivers was inspired by those beautiful memories, made only possible by my hard-working immigrant parents.

What is your favorite river?

The Merced River in the Yosemite Valley is number one in my book! I take my kids to Yosemite every year now so I can relive my childhood memories, and to make new ones with my husband and children.

Lastly, what drove us to purchase our East Bay home seven years ago was a tiny river in our backyard. Every day I get to go outside and listen to the creek’s waterfall and it’s my little private paradise. Sometimes there’s a group of ducks floating along, and hummingbirds buzzing about. Deer come and go, owls and hawks are my outdoor pets, and I once saw a river otter swimming and splashing around like he owned the place. My little river is a beautiful sight to wake up to. The river gives me life!

One of the primary concerns when planning for dam removal is the impact of sediment transport on water quality, river health, and the communities that depend on healthy rivers. Sediment forms when rocks and soil weather and erode. We think of rivers as something that moves water, but just as important is its ability to move and shape the earth. Sediment comes in all shapes and sizes—everything from silts and clays to coarse sand and gravel. Each of these kinds of sediment mean different things for rivers and aquatic life. Coarser material like gravel and sand often makes up the bed of the river and help create and maintain complex habitat upon which many aquatic communities depend. The presence of dams can starve downstream reaches of sediment, which can lead to increased bank erosion.

Dams create reservoirs and reservoirs accumulate sediment over time—more than 100 years in the case of the four dams being removed from the Klamath River. The degree of sedimentation downstream following a dam removal depends on multiple factors, such as sediment volume, sediment management plans (i.e., phased removal of a dam and passive release of material, dredging), the river’s geomorphology, and the composition of the sediment itself (e.g., fine grain, mud, or coarse). Studies of previous dam removals have shown the resilience of rivers following dam removals. Rivers have the capacity to recover from the influx of sediment after dam removal within a period of days to a few years and tend to thrive afterward. After an initial phase of disturbance following a large removal, the geomorphology of the river stabilizes as the river begins to heal.

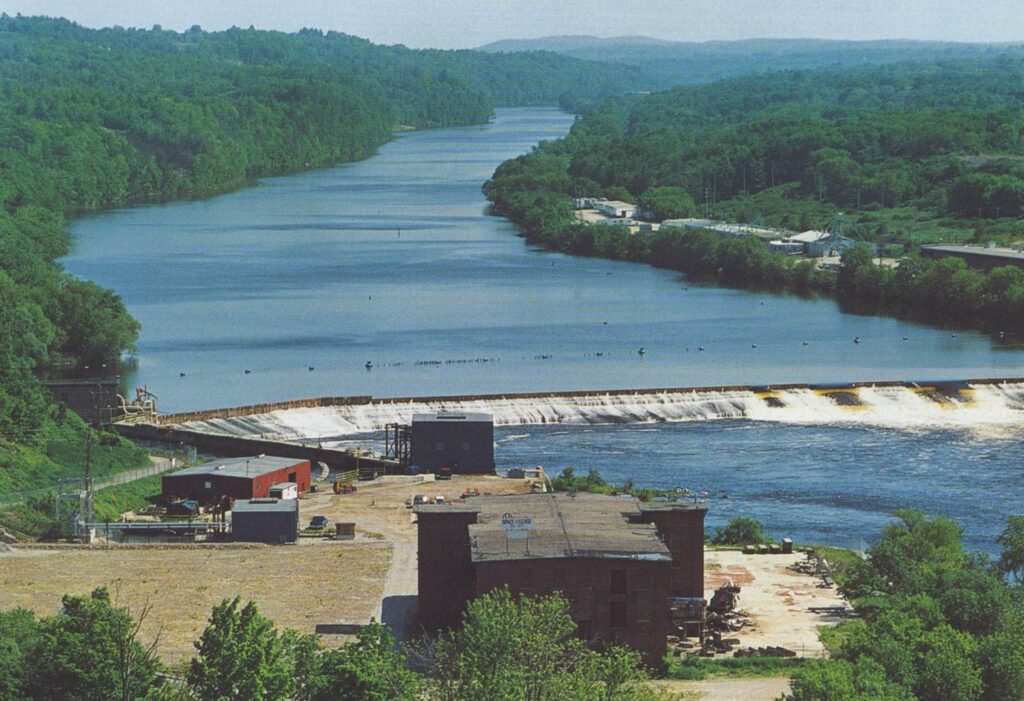

We can get a sense of how one day the Klamath River will thrive again by looking to other successful removals. The removal of Edwards Dam on the Kennebec River in 1999 is a story of restoration and revitalization. Its removal reconnected migratory corridors that had been cut off for 162 years, improving habitat for Sturgeon, alewife, eagles, and osprey. Millions of alewife now return to the Kennebec.

Another high-profile dam removal where passive release of sediment was utilized is the Condit Dam on the White Salmon River in Washington State. The 125-foot-tall Condit Dam impounded 2.4M cubic yards of sediment, 59% of which was comprised of silt, clay, and very fine sand. More than 60% of the reservoir sediment eroded within 15 weeks of breaching the dam Salmon and steelhead have rapidly recolonized the White Salmon River mainstem and tributaries thanks, in part, to natural river dynamics that allow these systems to recover quickly. In fact, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, redds were found throughout the former lake area less than a year after the dam was initially breached.

The 2018 Bloede Dam removal on the Patapsco River in Maryland serves as another useful case study. The 34-foot-tall dam impounded approximately 186,600 m3 of stored sediment, 50% of which eroded within the first six months following removal. River herring were documented (via eDNA) upstream of the former dam site within the first year following removal, and American eel populations skyrocketed from 36 in 2018 to more than 36,500 in 2022. Like the Klamath River dam removals, each of these removals entailed a period of recovery and depended on cross-sector collaboration and advocacy.

While the impacts of dam removals vary significantly, the evidence of the last 20 years points to the effectiveness of dam removal and the long-term benefits for communities, fish, and wildlife. With more than 91,000 dams inventoried by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and several hundred thousand more low-head dams, aquatic ecosystems in steep decline (freshwater ecosystems are dealing with extinction at twice the rate of terrestrial ecosystems), and the impacts of climate change altering weather and precipitation patterns threatening the stability and durability of water infrastructure, dam removal has become an increasingly urgent priority in terms of ecological health, community safety, and climate resilience. Simply put, the fastest way to heal a river is to remove a dam.

The flash flooding currently happening in Southern California and Nevada is the latest example of why we must transform the management and health of rivers and streams to strengthen communities in the face of climate change. Tropical Storm Hilary was the first tropical storm to hit California since 1939 and it has dropped historic amounts of rainfall on parts of communities from southern California to Las Vegas and across the Southwest. This event follows just weeks after major floods caused widespread damage across Vermont and the Northeast.

Climate change is fueling more frequent and intense storms, putting pressure on federal and state agencies to help communities manage the runoff and stormwater from these extreme events. This means adapting our existing infrastructure–elevating roads, expanding bridges, setting back levees- and it means making smart decisions about how we are developing along rivers and throughout watersheds.

American Rivers is calling on federal, state, and local governments to protect communities from increasingly severe flooding. Decision-makers must:

- Give rivers room to flood safely: Naturally functioning floodplains (the low-lying lands along a river) are a community’s natural defense against flooding. These areas soak up and store floodwaters and reduce downstream flooding. Keeping floodplains natural and undeveloped is the best way to avoid flood damage to begin with. Governments must prioritize protecting undeveloped floodplains and putting in place policies like the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard that require development to be resilient to Increasingly severe floods.

The fact is, many communities have already developed in their floodplains and have channelized and leveed their rivers, disconnecting them from their floodplains. All of this puts people and property at risk. Wherever possible, communities must work with residents and landowners to find solutions that improve their resilience and leverage state and federal funding to restore damaged floodplains to give rivers room to flood safely.

- Protect wetlands and small streams: The Supreme Court’s recent Sackett v. EPA ruling stripped federal Clean Water Act protections for small streams and 50% of the nation’s wetlands. These wetlands, along with perennial and ephemeral streams, are critical to public safety because they absorb and store floodwaters. By leaving streams and wetlands vulnerable to destruction and pollution, more communities are now at risk. State and federal decision-makers must shore up protections for wetlands to safeguard public health and safety.

This record Southwest flooding highlights the important connection between rivers and the ephemeral and intermittent headwater streams that lost protection under the Sackett case and are now at risk of unregulated development. Ephemeral and intermittent streams are dry for much of the year but fill with water during heavy rains. These headwater streams make up 81% of the arid and semi-arid Southwest and are the source of drinking water for people in the Southwest. Unchecked development on headwater streams could further increase future flood damage.

- Remove unsafe, outdated dams and levees: More frequent extreme rain storms mean more risk of dams, levees, and other infrastructure being overtopped or failing resulting in catastrophic loss of life and property. We cannot wait until dams fail to take action. Poorly maintained and improperly designed dams and levees need to be removed to protect downstream communities and infrastructure before they fail. States need programs that work with dam and levee owners to provide technical and financial support to remove dams and levees that they no longer want or need.

In addition, many dams are outdated and unsafe. Hundreds of dams have breached or failed in recent years because of heavy rainfall and flooding, putting communities at risk. The Association of State Dam Safety Officials estimates that aging dams across the nation need more than $70 billion in repairs.

Communities are not prepared for the increasingly frequent and severe flooding fueled by climate change. Our infrastructure was not built for this. We must help communities prepare, and that means protecting and restoring rivers. A healthy river is a community’s best and first line of defense against flooding and other climate impacts. When we pave over streams, disconnect floodplains, and destroy wetlands, we strip communities of these vital defenses. We must protect and restore rivers to make our communities stronger, safer, and more resilient.

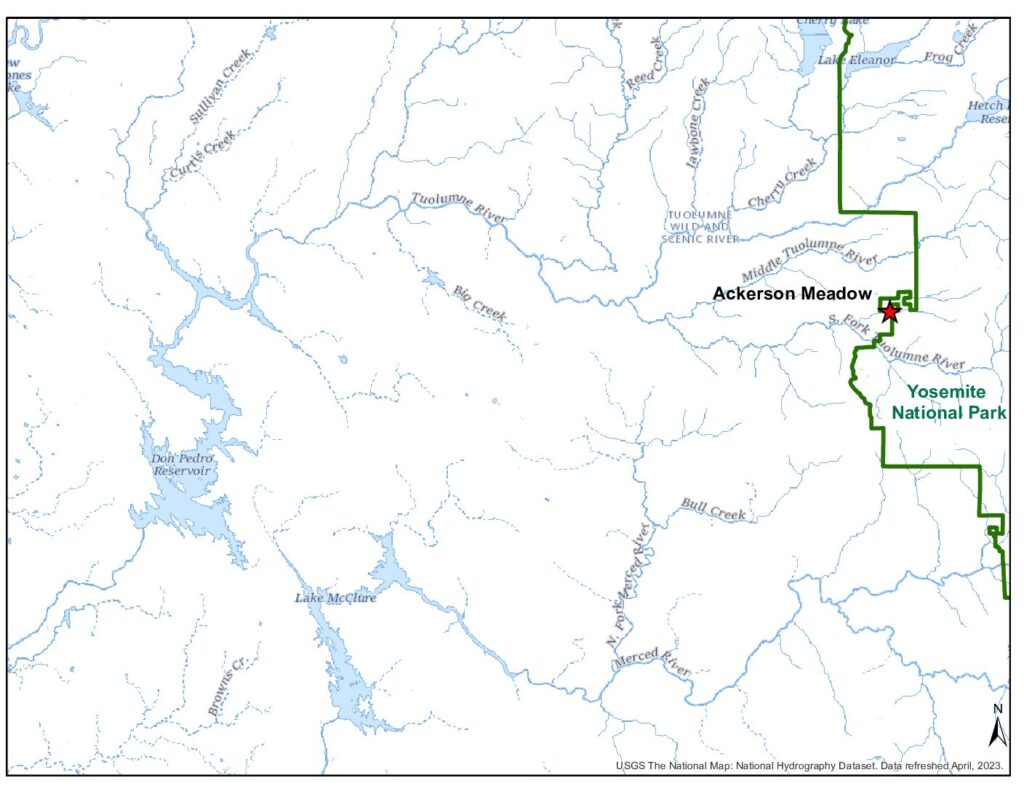

Shovels are in the ground, and the Ackerson Meadow Restoration Project is underway! Ackerson Meadow in Yosemite National Park and Stanislaus National Forest is one of the most significant biodiversity hotspots in the Sierra Nevada mountain range, providing habitat for two California Endangered Species (Great Gray Owl and Little Willow Flycatcher), a federally endangered species (fisher), a California Species of Special Concern and petitioned for Federal listing (Northwestern Pond Turtle), and a number of rare plants. And this is all despite Ackerson’s highly modified and degraded state. What might Ackerson Meadow look like when flows once again nourish the landscape? What native species might decide to make it their home?

The site’s restoration and biodiversity potential compelled the acquisition of Ackerson Meadow from a private landowner in 2016. This purchase, aided by American Rivers, National Park Foundation, National Park Trust, Trust for Public Lands, Yosemite Conservancy, and Yosemite National Park, was the largest addition to the park since 1949.

Since then, Americans Rivers, Stanislaus National Forest, Yosemite Conservancy, and Yosemite National Park have been working in partnership to realize the vision of a healthy Ackerson Meadow. The Ackerson Meadow Restoration Project shows the amazing work that can be done through diverse public-private partnerships. Multiple federal agencies, nonprofits, and foundations, and the state of California have come together to make this project a reality. In that sense, it is a significant landmark; however, the project will also be the largest “full-fill” (i.e., replacement of the meadow soils that have eroded away) meadow restoration project in the Sierra Nevada. Over the next two years, 150,000 cubic yards of soil (more than 15,000 10-yard dump trucks) will be used to fill in the eroded stream channel and restore the natural hydrology of the meadow. The restoration design also includes extensive revegetation of the meadow to enhance habitat for native species.

Why restore Ackerson Meadow now? After more than a century of degradation resulting from past land uses like road building, water diversion, logging, and grazing, the stream that used to spread out and slowly drain across the surface of Ackerson Meadow has now eroded fourteen feet into the meadow, constraining streamflow to an erosion gully, lowering the water table of the meadow. It was clear, even at first glance, that focusing our collective efforts on Ackerson Meadow could have a huge impact. Meadow restoration is incredibly important for reasons besides biodiversity: healthy meadows improve water supply and water quality, healthy meadows store groundwater that can support Californians during the warm summer months and periods of drought, and meadows, much like floodplains and wetlands, tend to filter pollutants, such as sediment and wildfire ash, out of our water. There’s also recent research demonstrating that functional healthy meadows are among the densest stores of carbon that we know of (they can sequester more carbon per acre than a tropical rainforest), but while in a degraded state, they are actually sources of carbon emissions to the atmosphere.

By scaling meadow restoration in the Sierra Nevada, we can address the ecological threats facing both California’s rivers and the communities that depend on them. Ackerson is a significant piece of a regional effort to create resilience in California’s headwaters. American Rivers is working alongside conservation organizations in the Sierra Meadows Partnership (SMP) to restore 30,000 meadow-acres by 2030. This partnership provides a roadmap for collaboration in the conservation sphere, and the ambitious goal of 30,000 acres depends on support from the state and federal government, tribal nations, conservation organizations, private philanthropy, and local communities.

Montana is known as Big Sky Country, the poster child for the great outdoors. When you visit, it all hits you – the lush green trees, abundant wildlife, wide open spaces, and crystal-clear waters. In the resort community of Big Sky, all of those things converge in the shadow of 11,167-foot Lone Mountain. What an ideal location for the 2023 Wildlands Festival.

This year’s Wildlands Festival at the Big Sky Events Arena was the second annual event. Produced by Outlaw Partners in partnership with actor Tom Skerritt, American Rivers, and Gallatin River Task Force, the festival was billed as “the largest event to ever be held in support of conserving the Gallatin River and rivers across the country.”

This year being the 30th anniversary of the release of A River Runs Through It, which was filmed on the nearby Gallatin River, it was fitting to partner with Tom Skerrit, who played Reverend Maclean in the film. Mr. Skerritt joined in the festivities and participated in a panel discussion during the fundraising dinner Friday night.

“Of the 50 years I was in Hollywood, that’s (A River Runs Through It) my favorite movie,” Mr. Skerritt shared.

It was a full weekend of opportunities for folks to learn about the importance of rivers and how they can help protect them. The weekend’s agenda included a dinner and silent auction on Friday and a star-studded lineup Saturday and Sunday featuring Lord Huron and Foo Fighters.

Despite the parade of thunderstorms and torrential downpours that rolled through each night, the show went on and the festival raised over $500,000 for river conservation. This incredible feat will support our work to protect one million miles of rivers in Montana and across the country.

“We’re working together with the Gallatin River Task Force to pass a bill called the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act that will permanently protect 20 of Montana’s most cherished rivers, including the Gallatin River,” said Scott Bosse, American Rivers’ Northern Rockies Regional Director.

We greatly appreciate all of our partners and the work they are doing to take care of our rivers, and we can’t thank Outlaw Partners and the other sponsors of this event enough. Through ticket purchases, silent auction bids, merchandise purchases, and generous donations, you supported us and the rivers. Without you, we couldn’t do this important work.

This weekend proved just how much Montanans love their priceless rivers. Now it’s up to the state’s congressional delegation to listen to them and take action.

For the rivers!

Farmers face some of the most daunting challenges to stay in business. Over the last decade, we’ve seen increased flooding which leaves many farmers, landowners, and ag producers at risk. The economic impact of severe storms, fires, drought, and flood disasters can be quite expensive. As a result, farmers experience crop loss, contamination, soil erosion, equipment and property loss, livestock loss, and debris deposition. This upcoming Farm Bill will provide the biggest opportunity to fight climate change and keep family farms and other small-scale producers financially sound so they can feed the world.

What Does the Farm Bill Mean for Farmers?

Every five years, Congress must reauthorize the Farm Bill to reassess, reevaluate, and reform key provisions to ensure programs from crop insurance to voluntary conservation practices are assisting everyday farmers. The bill includes $6 billion in annual conservation funding to improve soil health, restore watersheds, increase water quality, and protect wildlife while building resilience to climate change. The current Farm Bill expires on September 30th, 2023, and Congress is already drafting the bill.

Through USDA’s conservation programs, farmers are able to tap into innovative, nationwide on-the-ground technical support and financial assistance as a way to incentivize and implement best practices. These methods include building riparian zones, creating streamside buffers, and adopting easements to tackle excessive nutrient pollution among many other multi-use benefits. Strengthening key programs like the Water Source Protection Program, the Emergency Watershed Programs, the Regional Conservation Partnership Program, and the Environmental Quality Incentives Program are just a few examples where farmers, landowners, and ag producers need Congress to act to keep up with the constantly changing markets, global economic outlook, production demands, population growth, and climate change.

How Climate Impacts Rivers and Farming Communities

Across the nation, our research finds flooding has caused $59.2 billion in damages over the last decade. Over that same period, farmers enrolled in the Federal Crop Insurance Program reported $29 billion in damages caused by floods and excess moisture, with Upper Mississippi River Basin states representing 34 percent of those damages. The cost of flooding impacts is rising as precipitation increases, and damages are expected to continue to escalate as climate change impacts intensify.

In the West, acequias are falling through the cracks when it comes to fire and flood recovery assistance. Flood damage after the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon fire in the summer of 2022 impacted more than 700 people in New Mexico. The average market value for farms in the region is about $20,000. Yet these communities rarely receive any help. Local and state governments simply do not have the cash reserves to deploy financial resources to help small acequias associations. Rio Gallinas serves as a critical tributary to the Pecos River which is currently threatened by outdated watershed management plans. Traditional Hispanic acequia systems, with a 500-year history on the landscape, depend on the river to sustain agricultural and ranching communities. Unfortunately, these reoccurring natural disasters that farmers experience are making it harder to stay in agriculture.

As a third-generation farmer, Brian Wong, who owns and operates BKW Farms, grows crops including nearly extinct heritage grains like white Sonora wheat on 4,500 acres in the heart of the parched Sonoran Desert. His farm is about 25 minutes northwest of Tucson, Arizona. Bakeries, restaurants, breweries, and flour mills as far away as Minnesota and Florida rely on their grain to sustain their own businesses. But extreme drought is taking a tremendous toll on the Colorado River, the nation’s #1 Most Endangered River. In partnership with BKW Farms, American Rivers is urgently working with partners such as utilities, and municipalities to fix the massive imbalance between rising consumer demands and a shrinking water supply.

Congress Must Protect Farmers from Climate Change

Right now, Congress can make it easier for farmers to lead in innovation and conservation by making policy changes that will most effectively and efficiently encourage more farmers to adopt multi-use approaches for long-term sustainable agriculture which will help rivers bounce back. These program refinements and investments will not only improve water quality and quantity but also keep our farmers farming for years to come. We can maximize yields and ensure river protection by taking the following steps for a successful Farm Bill:

- Prioritize floodplain easements and other nature-based solutions with multiple-use benefits to address climate change.

- Promote the implementation of river and land management best practices paired with intentional and purposeful climate-smart goals.

- Support source water protection to reduce the risk of contamination to people, the environment, and wildlife.

- Increase drought resilience by enhancing water infrastructure to alleviate water shortages impacting vulnerable populations.

- Increase authorized levels of funding for programs that improve river health including water quality and quantity.

- Remove barriers to technical assistance and capacity-building.

- Increase funding for research and development on equitable and sustainable land and water stewardship.

- Assess the safety of dams, levees, and reservoirs, and improve rehabilitation of infrastructure and safety assessments.

See American Rivers’ Farm Bill Policy Priorities advocacy platform for more details.

Today, we’re continuing our work on Capitol Hill to advocate for key reforms that will restore rivers and revitalize farming communities for future generations. Together, we can ensure farmers are not left behind and their families can reliably and confidently depend on key conservation programs to withstand natural disasters. Congress must help farmers stay in business and ensure healthy rivers are a priority in the 2023 Farm Bill.

We urge you to send a message to your members of Congress. Will you join us?

June is National Rivers Month and summer is upon us! What better way to celebrate than getting out on your local river? There are many steps you can take to help keep our rivers healthy this summer, whether you’re having fun out on the water or recreating elsewhere in nature.

- Join an existing cleanup: check out our cleanup map to look for events happening near you!

- Connect with your local river outfitter: this is another great way to find fun events in your area led by experts in river health and safety. You can also reach out to other local parks or recreation departments, nonprofits, or recreation clubs which may also be hosting public cleanups.

- If there are no events near you, you can host your own cleanup!

Of course, you don’t need to join an existing cleanup to have an impact; you can still take actions to promote river health when you’re out on the river alone or with family and friends. It’s always a good idea to follow the “leave no trace” principles when recreating in nature to conserve the natural environment. These are small but impactful steps you can take to preserve your local river – for example, repackaging snacks and drinks into reusable containers to avoid leaving trash behind, looking up regulations and concerns for the area you’ll be recreating in, observing wildlife from a distance, and leaving natural objects as you find them. Even if you’re just lazing down the river, you can bring a mesh bag to collect trash as you’re floating by!

Whatever your plans, we wish you a fun and safe summer outdoors and hope you’ll join us in keeping our rivers healthy for many generations to come!

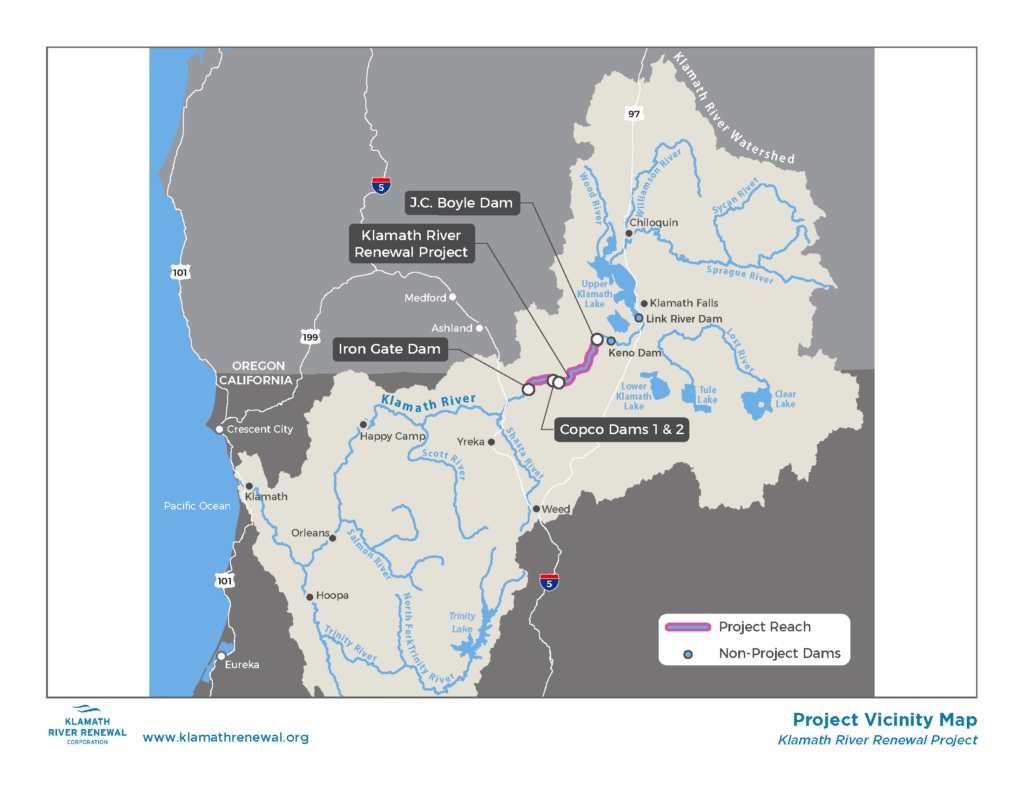

Update January, 2024: Copco No. 2 was fully removed in October 2023, marking the first of four dam removals along the Klamath River. The other three dams on the Klamath River that are part of this project are slated to begin removal in January of 2024!

For nearly 100 years, dams on the Klamath River have blocked salmon and steelhead trout from reaching more than 400 miles of habitat, encroached on indigenous culture, and harmed water quality for people and wildlife. The time has finally come for the four dams – J.C. Boyle, Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2, and Iron Gate – built between 1908 and 1962, to come down. This river restoration project will have lasting benefits for the river, salmon, and communities throughout the Klamath Basin. Here are 6 things you need to know about the Klamath River Dam Removals.

- One of the largest dam removals in world history

Four dams along the Klamath River, which runs from Oregon into northwestern California, are scheduled to be removed in 2023 and 2024 – Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2, Iron Gate, and JC Boyle. These dams total 400 vertical feet and choke fish passage along hundreds of miles of waterways, making this a historic opportunity and one of the largest dam removal projects to date. And construction has started! American Rivers is working in partnership with Tribal Nations, NGOs, the state and federal government, and local communities to ensure the health of the Klamath Rivers and the people who depend on its vitality.

- Tribal advocacy created this opportunity

Tribal nations whose ancestral lands and histories have intersected with the Klamath watershed since time immemorial – including the Hoopa, Karuk, Yurok, Shasta, Klamath and Modoc people – have spearheaded the collective effort to remove the Klamath dams. The health of the Klamath is a key facet of these peoples’ history, culture, and subsistence, and tribal leadership and perspective has profoundly shaped the course of events on the Klamath over the past two decades. Tribally led advocacy included a high-profile protest when Berkshire Hathaway and PacifiCorp executives visited the Klamath in 2020. River advocates, led by the tribal nations, pushed the executives to join the effort to remove the Klamath dams.

- Many years, many players, many obstacles

Dam removal is far from a linear process, and the journey to get to the key milestone of removal began decades ago. Though Tribes had been advocating for dam removal prior to a series of legal conflicts amongst rightsholders in the Klamath basin in 2001, a catastrophic fish kill in 2002 catalyzed wider action for dam removal. Following the fish kill, which resulted in the death of nearly 70,000 adult salmon, Tribes, NGOs, agencies, the States of California and Oregon, and individual rightsholders began working together collaboratively to address the health of the Klamath River and its communities and the movement towards dam removal began to gain momentum. Discussions around a far-ranging restoration plan in the Klamath basin began in 2005, with a proposed plan introduced to Congress in 2010. This initial legislation, the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement (KBRA), failed to pass through Congress. After the KBRA failed, several parties to that agreement worked to find a solution to dam removal, ultimately known as the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement (KHSA). The signatories to the KHSA, which include several NGOs, Tribes and the States of California and Oregon, created this plan as way to get dam removal done without having to seek Congress’ approval. Under the KHSA, the states and PacifiCorp take on the liability for and cost of the dams’ deconstruction, avoiding Congress entirely. This Agreement was signed in 2016, setting this new path in motion and creating the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, the entity tasked with removing the dams.

- Creating ecological resilience

Removing the Klamath dams promises a wide range of ecosystem benefits that enhance regional climate resilience and aid the imperiled salmonid populations that once surged into the watershed from the ocean (now only 5% of historic averages). Significantly, dam removal expands spawning habitat for fish. Damming on the Klamath has also contributed to warmed water temperatures, leading to toxic algae blooms and decreased dissolved oxygen in the river. By removing the four dams, we can help bring salmonid populations back from the brink, while restoring habitat for other species. Restoration doesn’t end with the removal of the dams: additional restoration on Klamath River tributaries is needed to enhance fisheries, as well as the other flora and fauna that depend on healthy rivers to thrive. Land that was formerly inundated in reservoirs will be revegetated with native plant species following dam removal through natural seed dispersal, assisted by a program to plant millions of native and culturally significant starts and trees, providing ecologically vital riparian habitat.

- Strengthening communities through dam removal

As salmon in the Klamath River have declined, commercial and recreational fishing have had to periodically close, impacting tourism, fishing, and other economic drivers. Dam removal along the Klamath will create newfound recreation opportunities for local communities, while also helping provide and sustain the comprehensive impacts healthy rivers have on communities, including subsistence. PacifiCorp also determined that dam removal was the best economic decision for ratepayers in the region.

- Key Dates to Know

June 2023 – The removal of Copco No. 2, the smallest of the dams, begins.

September 2023 – Full removal of Copco No. 2 and its related infrastructure is expected to be completed.

January 2024 – Reservoir draw down begins for Iron Gate, Copco 1, and JC Boyle and will continue through the spring. Once drawdown is completed, dam removal and lakebed restoration activities will begin.