There’s a lot going on in a river in the fall. Flows are changing and the temperature is dropping and there’s a bit of fish whimsy happening. In the October afternoon, as the gloaming comes on, the river margins of the Connecticut and other coastal rivers begin to pop and flash with glints of silver. These are the juvenile American shad who were born in the river a few months back and are soon bound for their journey downstream to the Atlantic.

At times I see hundreds of these little silver fish, just a few inches long, leaping a tiny leap out of the water making it ripple and flash in the low light of dusk. I’m told there’s no reason for the leaps, so I just assume the behavior is the group gearing itself up for the collective journey downstream to the Atlantic and their multi-year stint in the ocean as they mature into adults and prepare to return to their natal river to spawn.

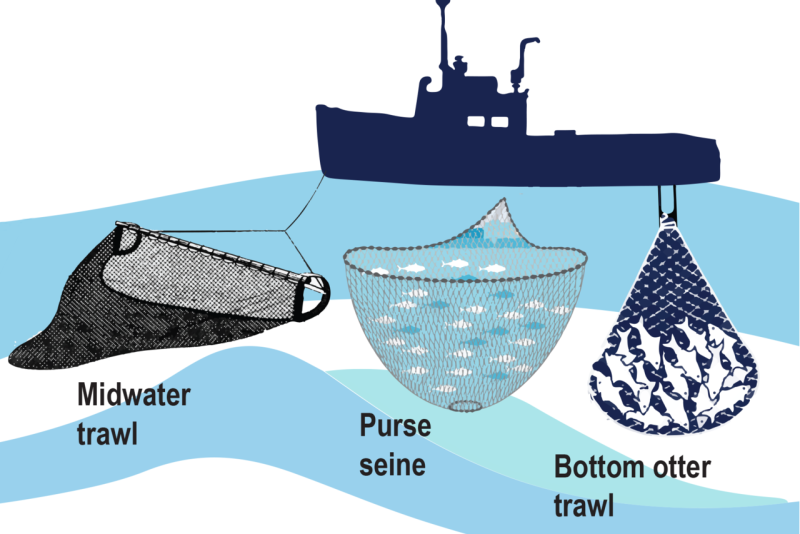

But in southern New England the journey into the Atlantic for these juvenile shad and their river herring colleagues is fraught. For too many years marine fish regulations in the waters off of New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and parts of Massachusetts have allowed overfishing of Atlantic herring. The damage to this ecologically and economically important fishery is a double whammy. Atlantic herring are different from the diadromous alewives, blueback herring, and shad that live in our rivers. But those river herring and shad that are heading out to the Atlantic this month will swim and live amongst the Atlantic herring. That means these river fish also end up in the nets with the Atlantic herring, which are being caught for their use as bait in the lobster industry, for fish oil, or sold as sardines. In regulatory lingo, the river herring and shad that are caught alongside the Atlantic herring are “by-catch.”

Stick with me here, fishing regulations are really complicated. I’m getting to the problem – and the solution!

Marine fishing regulations control amounts, gear, timing, location, and the number of times you can fish in a season. They also try to control by-catch by setting limits on how much non-target fish can be caught. Unfortunately, in southern New England, these regulations have allowed too many Atlantic herring to be caught and too much by-catch of river herring and shad. And the consequences of that have meant dramatically reduced spring returns in our river systems of those 3 and 4-year-old adults. And these reduced returns correspond to the timeframes in which the overharvesting of by-catch was being allowed.

Another way to demonstrate how marine fishing can impact our river herring and shad runs is to look north to the Gulf of Maine where diadromous runs are surging up rivers including those newly opened up due to dam removals and modern fish passage structures. The Gulf of Maine ocean fishing regulations include governing the time and location of Atlantic herring fishing in ways connected to spring migration season. These controls allow river herring and shad time in April, May, and June to head into rivers absent the boats and nets looking for Atlantic herring.

Dropping some regulatory-speak here – that type of regulation is called a time and area control. And American Rivers along with many other conservation organizations, small-scale fishing boats, and state agencies are working to re-establish time and area regulations in southern New England that will allow for a sustainable Atlantic herring fishery as well as rebounded river herring and shad runs.

So where’s that flash of hope?

In late September the New England Fishery Management Council took action to dramatically limit the Atlantic herring fishery due to overfishing, a limit that will effectively close the fishery. This will help to protect the river herring and shad returns for now.

The longer term work of the Council and other fishery managers is to continue developing the basis to reinstate time and area limitations as well as appropriate limits on by-catch in the waters of southern New England.

That work is a few years off and will undoubtedly be fought again by some of the commercial fishing interests. American Rivers will be there along the way with our many partners, scientists, and fishers to ensure our work to remove dams and reconnect thousands of miles of habitat for migratory fish is not for naught.

Want to dive into this issue? The New England Fishery Management Council has a lot of good information on this recent action. Forewarned for the novice – there’s more acronyms and statistics than you can imagine so gear up if you are going in!

Here’s some good general info on Atlantic herring and river herring and their fellow Alosine, the American shad

Our colleagues at the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership have a good website on the issue of forage fish and their connection to sportfishing that includes really great video.

Hand-thinning: The manual removal of vegetation in forested areas to prevent the spread and intensification of wildfire.

Mastication: The use of several different types of equipment to grind, chip, or break apart fuels such as brush, small trees and slash into small pieces.

Prescribed fire: A planned fire intentionally set by land managers to achieve management objectives such as wildfire mitigation or restoration.

These terms may be unfamiliar. In the Yuba River watershed, we are using these methods alongside our partners to manage the forests of the Sierra Nevada and create climate resilience, enhance public safety, and most relevantly to the name and mission of American Rivers, protect river health by reducing wildfire risk. The Hoyt-Purdon Prescribed Fire and Fuel Reduction Project will treat 570 acres within a 918-acre project area along the South Yuba River at a strategic location between the river and surrounding local rural communities. The project will use a combination of the approaches described above to reduce the risk of wildfire and increase forest and watershed resilience. The essential design will reduce the horizontal and vertical continuity of fuels (e.g. make it so fire can’t carry along the ground horizontally or get into the tops of trees vertically) to make it easier to fight a fire should it occur. The project is also designed to protect ecological function and sensitive species.

Hoyt-Purdon Fuel Reduction and Prescribed Fire Project in California

The Hoyt-Purdon Fuel Reduction and Prescribed Fire Project encompasses 570 acres of private land, extending along approximately two miles of the South Yuba River in Nevada County, California. The project will reduce wildfire risk and impacts for six nearby communities and the Yuba watershed, resulting in multiple watershed, ecological, community, and capacity benefits and will increase the pace of ecologically sound forest management in the long term.

At first glance, it might seem confusing that a river-centric nonprofit is involved in forest management and wildfire mitigation, but the impacts of catastrophic wildfire extend beyond the immediate physical destruction of ecosystems and property, and the release of smoke, having severe consequences for the headwaters of California’s rivers. High-severity fires burn vegetation and can even burns soils, preventing regrowth. This lack of vegetation eliminates cover and shade, which raises water temperatures for aquatic species and leads to less dissolved oxygen in the water, a key parameter for healthy aquatic ecosystems. Loss of vegetative cover also prevents precipitation from infiltrating the soil and leads to erosion, releasing sediment downstream and impacting key life-cycle processes such as spawning. On a community level, excessive sediment can disrupt the operations of key infrastructure such as water treatment plants and hydropower production, and if a fire is severe enough, erosion can even reduce the capacity of reservoirs downstream as they receive sediment and debris post-fire.

Fire has always been a part of the ecology of California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range, whether naturally ignited burns that arise from events like lightning strikes, or the prescribed burns by the Tribes that have lived in, cultivated, and stewarded the watershed since time immemorial. But a pattern of Euro-American fire-suppression that began in the 19th century has allowed fuels to build to dangerous levels across the range, putting communities and watersheds at risk from catastrophic high-severity wildfire. This is true of current conditions along the South Yuba River. The Hoyt-Purdon Project aims to address this by first implementing hand and mechanical thinning (i.e. mastication) to reduce vegetation to levels that allow for the safe reintroduction of fire. The project will then implement initial prescribed burning, with a plan to reburn the project area at regular intervals to maintain lower fire risk conditions. As temperatures climb with a changing climate, leading to hotter and drier summers and increasingly risky fire conditions, this work is more important than ever and needs to be scaled.

American Rivers is working to pursue integrated forest and watershed restoration in the California headwaters, recognizing the important role the surrounding landscape plays in protecting and maintaining downstream rivers. The Hoyt-Purdon Project will provide wildfire risk reduction at a strategic location between the South Yuba Canyon and adjacent communities including Nevada City and Grass Valley, thereby protecting both communities and the forested ecosystems that the South Yuba River needs to thrive. American Rivers and partners initiated project activities in spring 2024 and have completed significant hand and mechanical thinning. We plan to conduct initial prescribed burning in fall/winter 2024/2025.

This project and wildfire risk reduction and mitigation across the headwaters of the Sierra Nevada is only possible through strong collaboration. For this project, we are working with three different private landowners, and the project team includes Terra Fuego Resources Foundation, Open Canopy LLC and Stillwater Sciences, with funding from the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Bella Vista Foundation to restore a healthy fire regime to the Yuba River Canyon. Watch the video below to learn more about wildfire risk reduction and the projected impacts on the landscape!

This is a guest blog written by Julie Kramer, America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2024 Intern

What is it about a dry riverbed that brings so many people together? To outsiders, our desert rivers may look odd, uninviting, and honestly not much like rivers at all. As a resident of Tucson, the Santa Cruz River is my home water. I’ve ridden my bike along its banks numerous times, for simple enjoyment, world-class birdwatching, learning about watershed management and city water treatment, or to commute downtown. In any given month, you might find events in and around the river with the Feminist Bird Club, Sky Island Alliance, Tucson Birthplace Open Space Coalition, and Watershed Management Group, just to name a few.

I attended a Santa Cruz River Day of Connection event in April, to clean up a small section of the river within city limits. In the past three years, I’ve participated in a few river cleanups led by just one or two organizations and the turnout was often fewer than 25 people. The current collaborative efforts of Sonoran Institute with The Wilderness Society, Tucson Clean & Beautiful, Tucson Audubon Society, Ironwood Tree Experience and others have led to much higher turnout. In other words, hundreds of people are picking up debris in a single outing, removing thousands of pounds of trash from the river.

Luke Cole is Sonoran Institute’s director of the Santa Cruz River program within their Resilient Communities and Watersheds team. Starting in 2023, he began to connect a variety of local organizations to the cleanup efforts, and he added a DJ and food trucks for extra appeal. His plan is to host four of these cleanup days throughout the year, in February, April, October and December. This magic formula is not only bringing people together to clean our riverbed, but also showing what is possible on a much larger scale. Due to climate change, water scarcity and loss of federal protections, we have no time to waste in getting our river in the best shape of her life.

For thousands of years, this ribbon of water took care of the people and land of the Sonoran Desert. In turn, Indigenous tribes including the Hohokam, Pasqua Yaqui and Tohono O’odham were excellent stewards of the river. It takes an unusual path, flowing from the San Rafael Valley, into Mexico, then back across near Nogales on the border, turning north through Tucson. Outside interests like ranching and mining were first introduced to the area in the 19th century, relying heavily on the water supply. Rapid population growth and development in the 20th century increased demand for drinking water, agriculture, and industry, draining the river in a relatively short period.

We bent and shaped the river to our needs, often to the detriment of nature. Slowly but surely, we are returning this land and water to some semblance of former glory. In the past few years, treated wastewater has been released into the Santa Cruz River, encouraging fish and wildlife, as well as cottonwoods, willow, and other vegetation to return to this corridor. The City of Tucson and Pima County initiated a program to discharge the recycled water and it’s already making a difference.

The Santa Cruz River lives within Pima and Santa Cruz counties, firmly ensconced in the Sonoran Desert. This region receives anywhere from 3-15 inches of rainfall per year, with both summer and winter rains. The vegetation here is the most biodiverse of all North American deserts. Within the boundaries of the Sonoran Desert, public lands currently include Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, and Saguaro National Park. The proposal to establish more public lands in the form of an Urban National Wildlife Refuge, the first of its kind in Tucson, would help to secure the sustainability of the Santa Cruz River.

Throughout the world we have many examples of rivers that have been loved to death. In the case of the Santa Cruz River, the strong connections between residents and key regional organizations are showing that the opposite is possible, to love a river to life. I hope you’ll take action for the Santa Cruz, ensuring the future of this important waterway in the heart of the Sonoran Desert. The next cleanup events will be on Saturday, October 12th and December 14th. See you there?

Life Depends on Rivers℠. That’s why World Rivers Day is so important. Most people who live in America live within 1 mile of a river, they just don’t know it. This upcoming election will determine the fate of our nation’s rivers, yes, even the ones in your backyard, for years to come. That is why we encourage you to take the time this World Rivers Day and the days leading up to Election Day to get familiar with the candidates on your ballot and where they stand on your rivers and clean water.

Check out these four easy things you can do for World Rivers Day and be a confident voice for rivers come Election Day in November. Don’t forget – #VoteRivers!

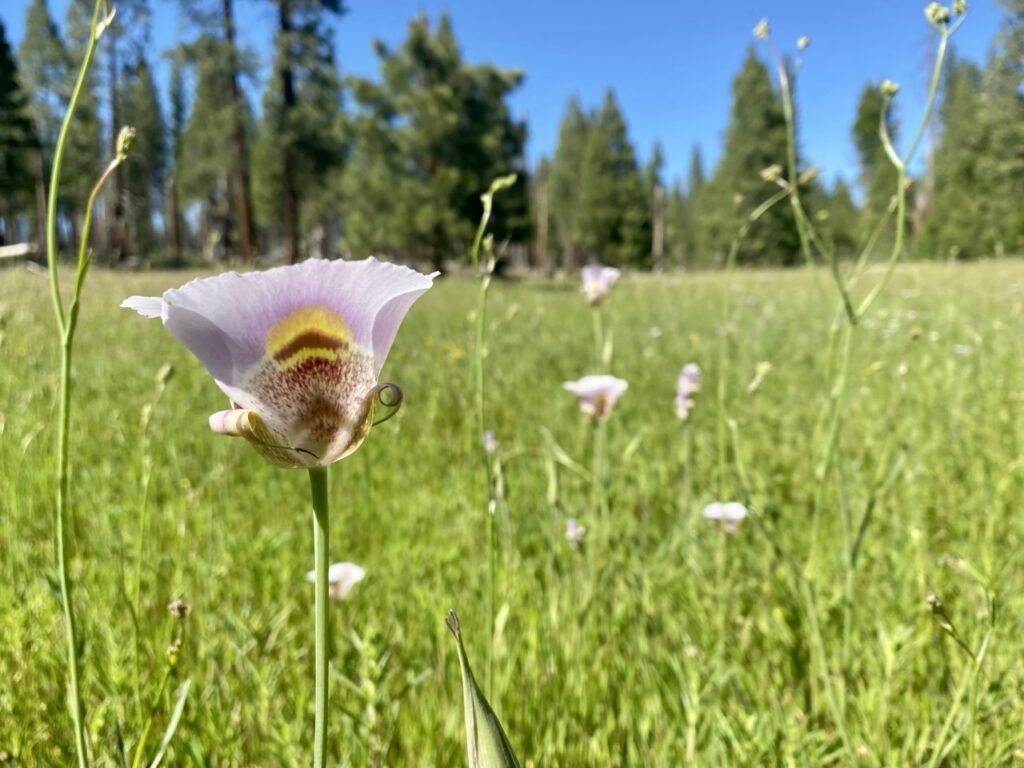

During the Californian winter and spring, the Sierra Nevada’s mountain meadows are covered in snow and inaccessible, so when the season shifts and the snow melts, we jump into action alongside our partners, putting boots on the ground and shovels in the dirt. Mountain meadows are critical to the hydrology of the landscape and provide a unique home to native plant and animal species, anchoring soil and storing groundwater. While they may be comparatively small in area, covering 191,000 acres of the Sierra Nevada, mountain meadows are critical to the health of California’s headwaters, which provide clean drinking water to more than 75% of Californians. Beyond this, they provide essential habitat, recreational opportunities, and increase regional resilience to climate change. With around 50% of the Sierra Nevada’s mountain meadows significantly degraded, scaling mountain meadow restoration across the Sierra Nevada is more important than ever.

Our Headwaters team leads meadow restoration from concept to completion, including initial assessment to identify meadows in need of restoration, design and permitting, on-the-ground restoration, and monitoring to quantify project benefits. And this summer and fall, our team has been in the field ensuring the health of Sierra Nevada mountain meadows. Read about our projects to stay in the loop on our progress!

Ackerson Meadow

Ackerson Meadow is a low-elevation wet meadow straddling the boundary of Yosemite National Park (YNP) and Stanislaus National Forest (SNF), and provides critical breeding habitat for the CA Endangered Great Grey Owl and Willow Flycatcher. Over a century of land use including logging, ditching, and grazing led to the deep incision of the creek that flows through the meadow, which empties into the Tuolumne River, and the dewatering of the meadow. This summer, work began on the second and final phase of implementation, which will culminate in the restoration of the upper meadow (158 acres). A healthy Ackerson Meadow means more habitat for a wide range of native species, expanded wet meadow vegetation, enhanced groundwater storage (an estimated 217 acre-feet per year) and water filtration, as well as increased carbon sequestration.

This is a collaborative project the partnership of American Rivers, National Park Service Yosemite National Park, US Forest Service Stanislaus National Forest, and the Yosemite Conservancy (listed alphabetically).This project was funded in part by the donors of American Rivers, Bonneville Environmental Foundation, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, California Wildlife Conservation Board, Google (in association with their Water Stewardship pledge and strategy), National Park Foundation (provided by The Coca-Cola Company, The Coca-Cola Foundation, and Stericycle), National Park Service (provided by Bipartisan Infrastructure Law-Ecosystem Restoration, Concessions Franchise Fee, and NPS Operations), US Forest Service, and Yosemite Conservancy (listed alphabetically).

Faith Valley

Faith Valley is a 200-acre wet meadow site in Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest (HTNF). American Rivers implemented Phase 2 of the Faith Valley Restoration Project in 2023 in partnership with the HTNF, which included installing 25 new Beaver Dam Analogues (BDAs), repairing 4 BDAs installed during phase 1 in 2022, and repairing the OHV road along the west side of the meadow. In 2024, the project team is conducting adaptive management to repair the BDAs installed in 2023, install additional new BDAs, and repair a rocked swale installed on the OHV road during Phase 2. These actions will ensure that the BDAs and road repairs continue to function effectively. Adaptive management work at Faith Valley is funded by the California Wildlife Conservation Board.

Log Meadow

Log Meadow is surrounded by Sequoia National Park’s Giant Forest, one of the world’s most important sequoia groves. Hand crews wrapped up the final season of implementation at Log Meadow in Sequoia National Park during summer 2024. After filling the main Crescent Creek gully during summer 2023, crews focused on filling two smaller ditches on the northwest side of the meadow this summer. Restoration at Log Meadow piloted a novel wilderness-friendly meadow restoration technique that involved harvesting meadow vegetation, mixing it with sediment sourced from the gully banks, and packing the resulting “haydobe” material into the gully. Work on Log Meadow this summer was funded by the California Wildlife Conservation Board.

Grouse Meadow

American Rivers and the Humboldt-Toiaybe National Forest implemented restoration at 40-acre Grouse Meadow in the West Walker River watershed during September 2024. Grouse meadow is located near the top of the Grouse Creek watershed, which is a tributary to the West Walker River. The meadow has numerous headcuts and gully features, including a large headcut near the bottom of the meadow that threatens to migrate upstream and “unzip” the relatively healthy meadow habitat upstream. Restoration work will include constructing a valley grade control structure at this large headcut, treating other headcuts in the meadow, filling the deepest gully reaches, and installing low-tech process-based restoration structures including Beaver Dam Analogues (BDAs) and Post Assisted Log Structures (PALs). Restoration at Grouse Meadow is funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and by Point Blue Conservation Science through the Sierra Meadows Partnership Block Grant Program.

What Does Meadow Restoration Have to do with Rivers?

Dr. Ann Willis took a moment on the American Rivers Tuolumne River trip with OARS to discuss why meadow restoration is critical to clean water and river health.

Wilson Ranch Meadow

Wilson Ranch Meadow (60 acres) was selected as a priority site for restoration during American Rivers’ 2017 assessment of meadows in the American River watershed, which overlaps significantly with Eldorado National Forest (ENF). The primary problem at Wilson Ranch was a road crossing at the top of the meadow. This crossing created a pinch point, channelizing flows entering the meadow, which resulted in a large gully cutting through the entire meadow. To address this, the project team replaced the crossing with a series of eight culverts and fully filled the gully with onsite soils to spread flows and improve groundwater storage! Now, after restoration concluded in October 2023, Wilson Ranch Meadow’s hydrology has improved significantly. In summer 2024, American Rivers and the Eldorado National Forest are conducting adaptive management at Wilson Ranch Meadow to finish filling the lower portion of the gully through the meadow to further improve site conditions. This work has also expanded the U.S. Forest Service’s capacity to conduct meadow restoration and enhanced the meadow restoration community of practice’s ability to implement this type of project across the Sierra Nevada. Funding for this project was provided by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the Wildlife Conservation Board.

Caldor Fire Meadows Assessment

American Rivers has been hard at work assessing meadow health within the Caldor Fire burn scar this summer. Following the catastrophic Caldor Fire in 2021, American Rivers collaborated with the Eldorado National Forest (ENF) to acquire funding for planning and prioritizing meadow restoration in the Caldor Fire footprint. Funding for this project was provided by the Inflation Reduction Act, Vegetation and Watershed Management Fund, and Sierra Meadows Partnership Block Grant through the Wildlife Conservation Board.

As I stood on a bridge and looked upstream along the Klamath River, I felt confused. For over 15 years, I had stood in the same stop and gazed on the earthen face of Iron Gate Dam. But on this day, I saw…space. Framing the edges of that space, I saw canyon walls, river bed, floodplains and terraces, and miles of vista.

I lost my dad last year, so I understand having the experience of noticing the absence of someone who had been monumental in my life – both physically and metaphorically. I understand the confusion that results from seeing a space where he used to be and being keenly aware of his absence. I noticed the absence of Iron Gate Dam in the same way – the loss of something that had been monumental in my life and in the lives of thousands of others. But unlike the absence of my dad, seeing the absence of Iron Gate Dam stirred feelings of wonder, joy, hope, and gratitude.

Undammed: The KLamath River Story

The history of water in the West has been shaped by conflict, greed, and scarcity, but in a remote pocket of Southern Oregon and Northern California, a different Western water story is taking shape. The largest dam removal in history is on the verge of completion on the Klamath River. This moment is the result of a historic decades-long Tribally-led campaign to free the Klamath River and restore salmon and steelhead populations, which are core to Native traditions and foodways. This is undoubtedly a huge triumph.

The first episode of this in-depth podcast dives into the past, present, and future of the world’s largest dam removal project and features Dr. Ann Willis, American Rivers’ California Regional Director.

We live in a world where we are experiencing seemingly insurmountable crises that threaten our way of life every day: human-caused climate change, biodiversity loss, and unfair practices. While we know people are causing these crises, it feels harder to believe that people can similarly act to solve these crises. The solutions feel too big and too complicated to achieve given the deep differences we perceive in one another.

But if there’s one thing I’ve learned in my time working in the Klamath, it’s that no matter what my preconception of others have been, we all share a core of humanity. When we come together and name the feelings and values we share, rather than categorizing our differences, we can accomplish amazing feats.

With the cofferdam gone at Iron Gate, we are part of a historic shift in how we exist with the Klamath River flows freely from Lake Ewauna to the Pacific Ocean. The Klamath River dam removals mark an inflection point from the past century, when the river was dominated by people who saw it as a catalogue of resources to be extracted and exported, to a new chapter where we more fully embrace a lesson from deep time: rivers have value in on of themselves, not just for the environment or fish, but for people, too. This is the moment where we give ourselves over to the belief that nature is a better steward of life than we are, where natural processes can take the helm.

For those of us who are nervous or afraid about following nature’s lead, consider that there are people who can guide us through this transformation in how we exist with a river. We often talk about people living in tension with or opposition to nature, but there has been a long history of life lived in alignment with nature that stretches back to time immemorial. Recognizing this goes beyond simply acknowledging the sovereignty and rights of Tribes; it means we might also begin to see how dam removal isn’t just a revitalization a river, but of traditions and ways of life that were demolished when these dams were constructed. The Tribes of the watershed and their relationship with the Klamath are truly the origin point of the movement to heal, and the most committed advocates for the river’s recovery. Working together has been an opportunity to learn about and begin the process of addressing historic unfairness to heal our relationships with each other, our histories, and the heritages and traditions that give our lives meaning.

With the removal of the final cofferdam and the dawning of the Klamath River’s revitalization, I have learned more than the power of collaboration. I have learned about the power of now: we don’t need to wait for generations to celebrate incredible milestones of success. We can celebrate all we can save right now. We can remove dams without displacing people. We can do it on time and on budget while undertaking critical work that sits in alignment with the needs of the environment. This incredible effort has created a much-needed precedent and expanded the vision for what successful dam removal can be.

Most dam removals will not share the scale of the Klamath. Most dam removals are small, but their cumulative impact is immense. No one project will solve all of our overlapping crises, but everyone has a role to play in the solution. I feel hopeful knowing that even though there’s still much to do, a lot has been accomplished. As we move into a future where more dams become obsolete, we can reflect on the success of the Klamath River and its people as a guide for how to move forward together.

Often, there is a naïve perspective that environmentalists are busy conserving natural land and protecting untouched waters. This may be true in some places, however, in many communities, natural lands are parking lots, streams are buried, and rivers are impaired. In cities, community members step up to challenge climate change and long-standing environmental burdens. As climate change intensifies, the frequency of climate-related threats impacting public health and safety is rising.

Over 50 years ago, Congress enacted the Environmental Protection Agency and federal regulations, like the Clean Water Act, to safeguard our communities from the harmful effects of pollution and to restore our urban rivers back to health. Today, more than 80% of rivers remain unsuitable for fishing, swimming, or drinking, and less accessible natural places are near Black, Latino, and Asian American communities. Decades of broken promises from federal agencies and local governments to reduce pollution and restore rivers ignited the next generation of advocates to speak out – loudly – on behalf of their communities.

A new generation of climate leaders is tackling local environmental challenges through culturally centered solutions, community-led science, and genuine conversations. Young environmental leaders are harnessing the power of new technology and social media to ignite a global movement for change. By leveraging these platforms, they are effectively mobilizing communities, raising awareness about pressing environmental issues, and advocating for innovative solutions. This new generation of activists is uniquely positioned to address environmental challenges through a holistic lens, recognizing the interconnectedness of ecological, economic, and social well-being. Their digital prowess enables them to build strong momentum, foster collaboration, and drive impactful change on a local and global scale. Nancy, a multidisciplinary artist in metal, ceramics, jewelry, and plants, shows up for community with nurturing love and support. Erica enjoys being outdoors and hiking, and with a contagious enthusiasm, she motivates action.

Recently, I had the privilege of catching up with a few of my local climate sheros in Grand Rapids over lunch in a nearby cafe. Erica Bouldin and Nancy Morales advocate for equitable access to natural spaces, investment to remediate brownfields alleviation, and inclusive participation in local decision-making.

Driven by a desire to connect with the community and bridge the gap between local issues and climate change, they created the Green Rapids podcast. Erica and Nancy wanted to create a fun and engaging platform to share not only the urgency of the climate crisis but also practical solutions and actions. Passionate about climate and environmental fairness, they bring the community access to critical information on environmental issues in our city and state and connect listeners to activism across the globe.

The Green Rapids podcast takes a refreshing approach to serious environmental issues, engaging its audience in pressing topics like flooding, air quality, pedestrian safety, and food access. With a mix of humor and expertise, the show delves into pressing ecological challenges while keeping the mood light. By interviewing local experts in a fun and engaging manner, Green Rapids makes complex environmental topics accessible and enjoyable for any listener. Our local partners, the West Michigan Environmental Action Council and the Lower Grand River Organizations of Watersheds, were featured on the podcast to share insights on the collaborative efforts, environmental practices, and river restoration. Carlos explains watershed on “Soak it All In” or catch the LGROW Flow and learn about the importance of Urban Waters Network for communities. Are you curious about the threats we can’t see? Listen to the Green Rapids conversation about More Than Water Under the Bridge.

As women of color, they emphasized their role as advocates for their communities, working to dismantle unfair policies and practices. However, they also highlighted the immense pressure they face to address the community’s needs. They shared the difficulties they face in a white-led environmental movement and the desire for traditional knowledge and cultural perspectives to be prioritized in land and water management.

Like any good tea, take a sip for yourself.

Green Rapids podcast is available on your favorite streaming app and social media platforms.

Green Rapids podcast is part of the Urban Core Collective. If you’re in the area, you can catch the Green Rapids podcasters at the Urban Core Connect event on August 22nd and learn more about the amazing work UCC does for the Grand Rapids community.

This guest blog was written by Anneli Chow, our summer California River Restoration Intern at American Rivers

Where Great Valley Grassland State Park’s single boat ramp meets the San Joaquin River, the water ripples with non-native mosquito fish, darting aimlessly in the murky water. Sparse riparian vegetation along the river bank provides little protection from the stinging Central Valley sun. Dry floodplains surround us, and a single social trail, an unofficial trail formed from people repeatedly walking that way, winds through the tall invasive plants that thrive on the unnaturally parched land. I wonder how many cars whooshing by on the Central Yosemite Highway know that the space they’re passing is a state park.

At Great Valley Grasslands State Park (GVGSP), American Rivers is combining levee deconstruction, native plant revegetation, habitat restoration, and community outreach to conserve one of the California Central Valley’s last native grasslands, restore the San Joaquin River’s natural floodplain hydrology, and create an accessible and inclusive community space for recreation, environmental and cultural education, and stewardship. When I first visited GVGSP with my supervisor and Associate Director of California River Conservation at American Rivers, Kristan Culbert, during the second week of my internship, I was still grasping the multipronged goals of this project. But even then, seeing invasive species growing over the floodplains, feeling the warm and turbid water, and wishing there were more signs to engage with communicated one thing clearly: this place holds so much potential.

Back in my home office, something else strikes me. This expanse of native grassland sits amidst acres and acres of agriculture fields, like a diamond in the rough. I wonder why this land, seemingly suitable for plowing and planting rows of crops, hasn’t been changed, seeing as agriculture is the most lucrative sector of the San Joaquin Valley’s economy. But relief races my wonder and wins. California’s Central Valley has some of the poorest access to green spaces in the nation, and growing up in the Pacific Northwest made me confident that green spaces – that protect the liberty to walk without waiting for cars, breathe air exhaled by plants instead of pipes, and bathe in the sight, sounds, and streams of free-flowing water – are worth fighting for. Thank goodness this grassland remains.

GVGSP has survived over a century of development, but it needs lots of love. To share this newfound affection for the park, I started creating a factsheet. A few iterations and some suggestions from the Central Valley and marketing teams culminated in a four-page magazine-like spread that tells the stories of habitat fragmentation faced by native wildlife like the San Joaquin kit fox, Chinook salmon, riparian brush rabbit, and fairy shrimp. This piece is both a plea to slow the growth of state and federal listings of endangered species, and a plan for doing so, illuminating the restoration and river-floodplain reconnection work American Rivers champions. It will be distributed to the public, policymakers, and decision-makers, and join a bank of American Rivers factsheets. My hope is that it will convey that GVGSP will one day be a properly accessible park, but it is a home to wildlife first.

Still, in line with the demands of multi-benefit restoration, American Rivers aims to do it all. The Grasslands Floodplain Restoration Project places a strong emphasis on soliciting community input to ensure park infrastructure, interpretation, recreation, and educational opportunities are accessible and aligned with local community needs and wishes. In preparation for public outreach events, I used CalEnviroScreen 4.0, municipality websites, and even a trip to the Hilmar Cheese Company to research community demographics, environmental exposure burdens, and existing community spaces. This information illuminated much about the towns surrounding GVGSP, such as Gustine, Stevinson, Hilmar, and Merced, and came in handy when writing a Public Access Scoping Report and community survey questions. Writing this report was an opportunity to be clear-eyed and critical about the existing conditions of GVGSP, but it also allowed me to imagine people using the park, and push this vivid vision for their sake.

During my internship, I also got to visit Dos Rios State Park, California’s newest state park, located about thirty-five miles north of GVGSP. Here, I witnessed an actualization of the improvements I imagined for GVGSP, and the progress that can come of pursuing a vivid vision. We waited for a few minutes, then the wooden gate before us began to slide, revealing the entry path into the park. A sleek California State Parks pickup truck led us to a parking lot demarcated by evenly-spaced boulders.

We were greeted with a warm welcome from park interpreter Julian Morin, who invited us into his truck to begin a guided tour. Julian drove us slowly through dense vegetation, a green marshy area, and the shade of valley oaks and Fremont cottonwoods. He pointed out lines on the tree trunks that show how high floodwaters can rise in the park. We stopped often for quails crossing the trail, because here, they have the right-of-way. We observed a water pump and cement pillars, which comprise the irrigation system supporting the newly restored plants. We spotted a Swainson’s hawk soaring purposefully above an area with bunny mounds and blackberry shrubs. After the tour, some of the other CA State Parks staff invited us into their office for water and shade, and we talked amiably about the Parks Online Resources for Teachers and Students (PORTS) program and an NPR team coming tomorrow to promote the park opening. Though everything was still emerging at Dos Rios State Park, everything already seemed to be thriving. Dos Rios was a simple space, but it felt inviting, safe, shady, and green, the hallmarks of a greenspace. There is so much work to be done to reach this state at GVGSP, but that means there is also so much potential. Working on this planning project has helped me see it as a space that will one day be the place people didn’t know they needed.

As my internship concludes, I want to thank Stanford University’s Bill Lane Center for the resources and support they have provided to allow me, and many other interns, to contribute to meaningful work in American West. I also want to thank my supervisor, Kristan Culbert, the Central Valley team, and all the American Rivers staff who have helped me feel welcome and trusted me with worthy work. Most of my interactions were over Zoom or Slack, but my coworkers’ humanity, humility, and support always showed, testifying to the incredible interconnectedness and robustness of this remote workplace. Over only a couple of weeks, I came to understand that American Rivers is able to create impact from the local to national scale because everyone’s investment in each others’ work, wellbeing, and ideas supersedes any desire to simply clock in and clock out. Whoever I was meeting with would always ask me about my work and interests, and I often concluded 1:1 meetings with an abundance of resources and an invitation to chat again. Working as part of the American Rivers community has been fulfilling and inspiring to say the least. I’ll definitely be taking up those invitations.

Anneli Chow’s internship was sponsored by the Bill Lane Center for the American West. This piece was originally published on the Bill Lane Center’s Out West Student Blog. You can learn more about the Bill Lane Center at their website (west.stanford.edu).

As someone who has spent his career working to save rivers, I’ve had the opportunity to explore some of the most spectacular waterways North America has to offer. Some of my favorites include the Middle Fork Salmon River in Idaho, the Middle Fork Flathead River in Montana, the Skeena headwaters in British Columbia, and the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon.

While all these rivers are special, none, for me, compares to the Alsek. This remote, relatively obscure river flows for 174 miles from its headwaters in the Yukon Territory, across the northwest panhandle of British Columbia, then makes its final run to the Pacific Ocean through Alaska’s Glacier Bay National Park. Among its superlatives, the Alsek traverses the largest non-polar icefield, the largest protected wilderness area, and the second highest coastal mountain range on the planet.

Back in 2012, a friend of mine from Montana who had guided on the Alsek for years invited my wife and me to join him on a private trip down what he called “the wildest river on earth.” We jumped at the opportunity, and that August, fourteen of us embarked on an epic two-week adventure. The thing I remember most about that trip was the bears – we saw 53 of them, including one large male grizzly that charged full speed into our camp when we were cooking bacon on the first morning.

There are precious few trips that are truly life-changing. That trip down the Alsek was one of them for me. I had to totally recalibrate my concept of wildness.

I never thought I’d get a chance to return to the Alsek. But then a few months ago, American Rivers’ President, Tom Kiernan, had to drop out of an Alsek River donor trip due to an injury. The main purpose of the trip was to discuss with our supporters how we plan to expand our river protection work in Alaska. I was asked if I could take his place. I felt terrible for Tom because I knew how much he was looking forward to this trip, but I could barely contain my excitement at the prospect of returning to the river that had so captivated me.

So, on the summer solstice, my wife and I flew from our home in Montana to Juneau, Alaska, where our adventure began. Early the next morning, we boarded the ferry for the four-hour trip up the Lynn Canal to Haines, where we met the other trip participants and guides at the historic Hotel Halsingland that evening. As the guides handed out personal river gear to everyone, I felt the same giddy anticipation that I felt 12 years ago.

Our expedition team included five highly skilled guides from Haines Rafting Company; American Rivers’ Northwest Regional Director, Sarah Dyrdahl; a mother-daughter duo from Wyoming; a retired couple from Sitka, Alaska; a gentleman in his 70s from California who once hiked the entire the Pacific Crest Trail; another gentleman in his 70s from Florida who had never camped before; a whip-smart young investor from Colorado; a professional photographer from Haines; and my wife and me.

The following morning, we made the three-hour drive to Haines Junction in the Yukon Territory, checking in at the international border station along the way. From there, we drove another hour on a rough four-wheel drive road to the put-in on the Dezadeash River. After loading our rafts in a light drizzle, we were finally ready to launch into the great beyond.

A few hours into our float, we spied a grizzly bear swimming across the river a few hundred yards downstream. It disappeared into a thick patch of willows on a peninsula right where we planned to camp for the night. “Here we go again with the bears,” I thought to myself. But the only large animals we saw that evening were a dozen trumpeter swans in a backwater slough.

For the next several days, we made our way down the upper Alsek, marveling at the glacier-polished landscape and soaking in the warm sunshine. As we approached our camp at Lava Creek, we pulled over at a familiar point on river right where one of our fearless team members, Ariana, took a swim in a gin-clear pond while the rest of us hiked around on the sand dunes and rock outcroppings. On that upper section of the river, the land is so freshly sculpted it feels like you’re floating through the Pleistocene. You half expect to see a wooly mammoth around each bend.

On day three of the trip, we arrived at iceberg-studded Lowell Lake, created by a 50-mile-long glacier that dammed the entire width of the river not long ago. Words can’t describe the beauty of this place. We camped beside the lake for two nights, spending our days hiking, swimming in off-channel ponds, and glassing for wildlife. We had planned to climb Goat Herd Mountain, which affords dazzling views of the 15,000-foot-high Hubbard massif, but a swollen side-channel of the river blocked our way. In the evenings when the sun dipped behind the mountains, we sipped tequila by the campfire and listened to the faint roar of distant waterfalls and the occasional thunderclap of calving icebergs.

As we departed Lowell Lake through a maze of icebergs, we entered the most perilous whitewater section of the trip – first Sam’s Rapid, and then Lava North (named after the notorious Lava Falls rapid in the Grand Canyon). We pulled over on river left to scout our line through Lava North. You don’t want to flip your raft here, as the consequence is a long and harrowing swim in 35-degree water. Only after we made it through safely did we hear the story of one of our guide’s friends who did just that, got sucked down into a thundering hole, and “saw the darkness.” He hasn’t rowed the river since.

As we made our way downriver, both the mountains and the river grew in size, making our rafts seem like tiny specks in comparison. We arrived at the entrance to Turnback Canyon and pulled into the portage camp on river right. As we unloaded our gear from the rafts, someone noticed a chocolate-brown sow grizzly and her three cubs at the foot of an alluvial fan across the river. We took turns looking at them through binoculars for hours.

Later that afternoon, we took a short hike onto the Tweedsmuir Glacier until we got bogged down in knee-deep mud. The glacier hems the Alsek River against a waterfall-studded mountainside, turning it into an unrunnable maelstrom of whirls and boils. The only way rafters can get around the canyon is via a helicopter portage. So, we got up early the next morning, wolfed down breakfast, and laid out all our gear in neat piles so the helicopter could haul it in a cargo net dangling from a longline. Once the helicopter transported us and our gear around the canyon and onto a sandy island, we reinflated our rafts, reassembled the frames, and reloaded our gear. The whole operation took four trips and about three hours.

Downriver from Turnback Canyon, the climate rapidly changes from continental to coastal. As we made our way towards our camp at the confluence of the Tatshenshini River, we added layers of clothing to ward off the damp chill. The confluence is one of those power spots that heightens all your senses and makes you feel incredibly alive. On maps, it is known as the Center of the Universe because there are petroglyphs carved into a rock outcropping on a nearby island that tell the story of how the world was created.

Before we departed the confluence camp, we gathered in a circle on the beach to share the story of how, over three decades ago, U.S. and Canadian conservationists fought off the proposed Windy Craggy copper mine. At the time, it was called the most environmentally destructive project ever proposed in Canada. It would have lopped off the top 2,000 feet of Windy Craggy Peak, sending acid mine drainage into the Tatshenshini and lower Alsek rivers, devastating their salmon fisheries. After a long battle, the Canadian government designated the Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Wilderness Park in 1993, closing the door to future mining. A year later, the area was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Below the confluence, the Alsek doubles in size and glaciers and waterfalls plunge into it from every direction. While there are no large rapids in this reach, rowers must stay laser focused and follow the deepest channel in the labyrinth of braids, lest you run aground on a submerged sandbar or worse yet, get carried across the floodplain and separated from the group. In the latter case, you might not reconnect with your party until the next day.

The last major landmark on our trip was Alsek Lake, the entrance to which is marked by a distinct promontory known as Gateway Knob. You can enter the lake through one of three doorways. We chose door #3, to the right of the knob, because you can get your rafts trapped in a dangerous traffic jam of constantly shifting icebergs if you enter through the other routes. We set up camp on a wildflower-spangled beach, then scrambled up to the top of the knob through a dense forest of alders and devil’s club. From that vantage point, we could absorb the grandeur of the landscape we had traversed over the past two weeks – the huge, silt-laden river slithering across its floodplain like a thousand snakes, the massive glaciers pouring off the Fairweather Range, and the giant icebergs sailing across the lake like frozen ocean liners.

On our last morning, we rowed across the outlet of the lake in a silvery fog, then made our way downriver, escorted by icebergs that occasionally would hit the bottom, rear up, and then roll over. Arriving at the takeout near Dry Bay, we formed a firemen’s line to unload our gear from the rafts for one last time. Soon, our bush plane would arrive and fly us up the coast to Yakutat where we would say our farewells, catch our commercial flights, and go our separate ways.

Epilogue – On July 20, two weeks after our trip ended, a small plane carrying our bush pilot, Hans Munich, and his partner, Tanya Hutchins, disappeared on Mt. Crillon in the Fairweather Range in poor weather conditions. A few days later, the U.S. Coast Guard called off the search for the plane and its occupants. Our hearts go out to all who knew them.

Here in Montana, we like to gamble, as evidenced by the hundreds of small casinos scattered across the state. But we’re gambling with the health of downstream residents by storing decades of industrial waste in the floodplain of the Clark Fork River while we cross our fingers that the next big flood never happens. Tons of industrial toxins could wash down the Clark Fork River. It could happen next year. It could happen ten years from now. It’s not a matter of if the next big flood will happen, but when.

And when we double down on flood risk coupled with industrial toxins, the stakes are just too high.

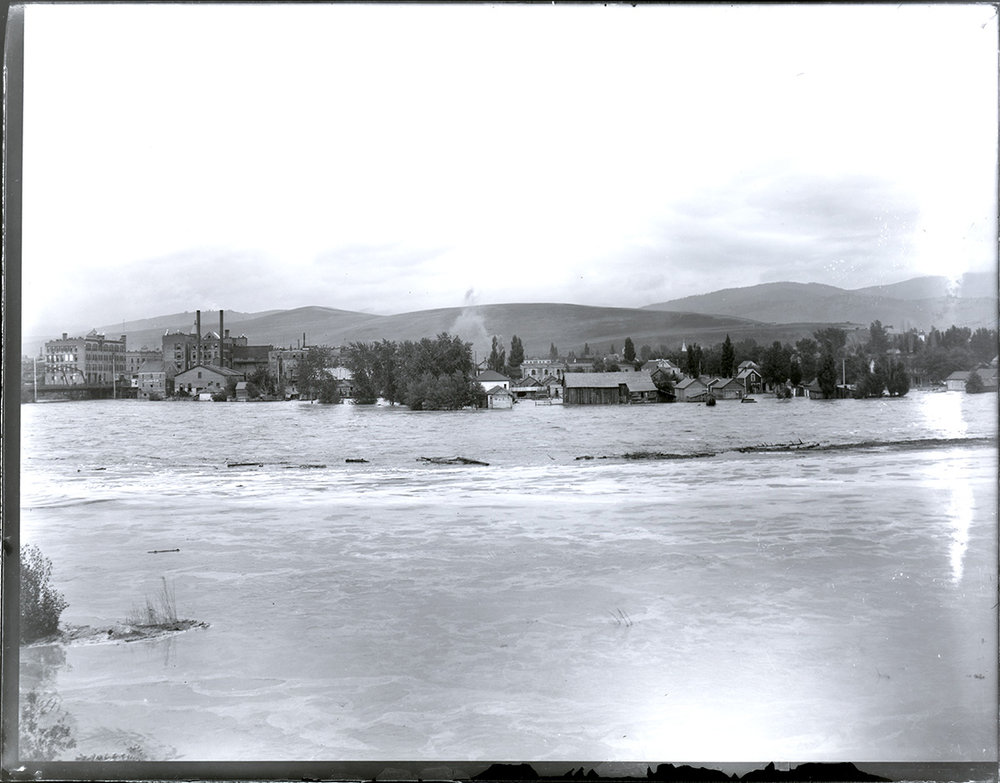

For over a half-century ending in 2010, the Smurfit-Stone pulp mill along the Clark Fork River near Frenchtown, Montana produced cardboard. Industrial processes to manufacture parts of cardboard boxes left tons of hazardous cancer-causing toxins including heavy metals, PCBs, dioxins, and furans strewn across nearly 1,000 acres next to the river. These toxins have been partially protected from flooding by a decrepit gravel berm separating the mill from the river channel. But a recent berm failure study commissioned by American Rivers and the Clark Fork Coalition predicts a scary re-enactment of the infamous 1908 flood and the toxic waste it swept downstream.

The 1908 flood is the largest on record for the Clark Fork River. It inundated portions of Butte and Missoula, washed out numerous bridges, threatened the then-new Milltown Dam, and dispersed copper mine waste for more than 100 miles. More than a century later, we are still in the midst of grueling, complex efforts to clean up this waste. Sadly, a complete cleanup is simply not possible. Back then, it would have been very difficult to anticipate the catastrophic outcomes of such a large flood, but we know better now.

Estimating the size of future floods requires extending beyond the historical record, and the use of climate forecasting tools to describe expected changes in local river systems. As climate change continues to tighten its grip on the Northern Rockies region, we can expect a shift in the causes, timing, and frequency of higher flows in western Montana, with less snowfall and more rain. Floods triggered by heavy rain, or rain-on-snow, can raise river levels faster and more unpredictably–just like during the 2022 Yellowstone River flood. The chances of that flood happening in any given year were infinitesimal–less than one-in-a-thousand. Yet it happened less than three decades after back-to-back 100-year floods wreaked havoc on the upper Yellowstone River in the mid-1990s.

We now know that a catastrophic flood on the Clark Fork River would breach the berm at the Smurfit-Stone pulp mill and could deposit industrial waste for miles downstream. While catastrophic flood risk may be small for any given year, that risk compounds over time the longer we wait for a cleanup. The extreme toxicity and persistence of waste at the Smurfit-Stone pulp mill underscores the need to consider flood risk over generations and to avoid leaving waste in place long-term, as has happened elsewhere across Montana.

American Rivers and the Clark Fork Coalition are calling on the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to include the 2024 berm failure report in its risk assessment for the Smurfit-Stone pulp mill. Ensuring that flood risks inform cleanup plans means completely assessing waste stored in – and next to – the floodplain without delay and adopting a cleanup that removes waste, eliminates the berms, and fully restores the floodplain.

At the Smurfit-Stone pulp mill, the consequences of a future flood just aren’t worth the gamble.

Help safeguard the Clark Fork River – Tell the EPA to take flood risks seriously!

Co-authored with: Sam Carlson, Staff Scientist, and Andrew Gorder, Legal & Policy Director, at the Clark Fork Coalition work to protect and restore the Clark Fork River. Together, Clark Fork Coalition, American Rivers, and other partners commissioned the berm failure study from River Design Group, a local engineering firm.

A benefit of working for a river conservation group as an avid angler is that you have a chance to get to know some excellent fishing rivers. This past month has been a great example of that, where I’ve been able to visit some amazing rivers, many of which American Rivers has worked on.

The month started on a small tributary to the Watauga River. American Rivers and Mountain True were spearheading the removal of Shull’s Mill Dam on the Watauga, which is a special river to me because that’s where my dad taught me to fly fish. Seeing the dam come out was meaningful, and catching trout in a healthy feeder stream nearby made it even more so. When a river is dammed, there’s nothing better you can do for it than taking the dam out.

From there I had a chance to fish on the Penobscot River in Maine. This river benefited from two major dam removals and a fish ladder around a third that were done about ten years ago in collaboration with the power company that owned the dams. The negotiated deal allowed the power company to generate more power from their tributary dams, and the native fish (Atlantic salmon, alewife, herring, etc.) got access to 1,000 miles of spawning habitat. That’s a huge number

and the fish are now returning in record numbers. And by the way, the fishing was tremendous – working the banks with popping bugs for eager smallmouth bass – and it was fun to be joined by a local Bald Eagle who fished near us.

The next trip was a driving tour of Wyoming trout streams with my son. We have been taking fishing trips since he was about six, and they just keep getting better. Our first stops were tributary streams to the Snake River near Jackson – cold, crystal-clear creeks that hold native Fine Spotted Snake River Cutthroat Trout. That’s kind of a mouthful, but the fish are gorgeous and have been there since the Ice Age. When you hold them near the river bottom, you can see how their colors match the colors of the rocks, and they blend in perfectly. All these streams have been protected by “Wild and Scenic River” designations (led by my colleague Scott Bosse several years ago), so the creeks and the fish will continue as they were meant to be forever.

From there we went up to Yellowstone National Park where we fished for native Yellowstone Cutthroats. If you’ve not been to the Lamar Valley, I would highly recommend it. Driving past herds of bison and pronghorns was thrill enough, but then to catch native Cutts in the beautiful Soda Butte Creek was icing on the cake. Though crowded, if you’re patient and careful, the fishing is tremendous.

After Wyoming, my son and I met up with the rest of the family in northern California. We stayed on the Middle Fork of the Feather River, which glistens beautifully in the morning sun. Like the Snake River headwaters mentioned above, the Middle Fork of the Feather River is protected by “Wild and Scenic River” designation. There are some small streams that feed into it that have clear, cold water that support native Rainbow trout, which my daughter and I love to fish for. Sometimes they jump several feet out of the water – pretty impressive for a six-inch trout.

For me, my love of rivers is coupled with my love of fishing. We’re blessed to have such wonderful rivers and fishing in this country, and American Rivers is working to keep it that way.

Good luck the next time you’re on the water.

Michigan is a state defined by water. Well known as a Great Lakes state, Michigan also has 51, 438 miles of rivers and is home to some of the most outstanding rivers in the contiguous United States: the Au Sable, Manistee, and Pere Marquette rivers in the south and the Presque Isle, Ontonagon, and Paint rivers in the Upper Peninsula to name a few. Thankfully some of these rivers, especially those in the northern part of the state, are permanently protected either as nationally designated Wild and Scenic Rivers or as Michigan Natural Rivers under state law. American Rivers is working with its partners to enhance these protected rivers and explore opportunities to protect more rivers — including the Huron River in southeastern Michigan.

This continues a legacy of work by American Rivers going back to the 1980’s, when we, along with local river groups and the Michigan United Conservation Clubs, championed the Michigan Scenic Rivers Act which protected 569 miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers. Today, Michigan has more protected miles of rivers than any state east of the Rocky Mountains.

Many of the state’s most outstanding rivers are part of the National Wild and Scenic River System, supporting habitat, clean water, and recreation for surrounding communities. American Rivers recently surveyed local river groups and state and federal agency staff to assess the opportunities to protect more rivers and streams and improve stewardship for currently protected rivers. Based on the feedback, we are leading efforts to explore improving stewardship, increasing restoration funding for protected rivers, and seeking new protections for rivers such as the Huron River, a candidate for a Partnership Wild and Scenic River study and designation. This designation would substantially increase annual funding to support the successful restoration and stewardship of this outstanding river.

The Huron is known for having outstanding fishing and recreation and the river hosts a number of historic and Native American village sites. The river provides for a wide range of quality gamefish species such as smallmouth and largemouth bass, trout, and steelhead. The Huron River Water Trail, a part of the National Water Trails System provides an exceptional 104-mile-long water-based recreational opportunity for paddling, fishing, and hiking through a significant number of public access sites.

American Rivers is working with our partners to actively explore the Huron River for Partnership Wild and Scenic River status. We are especially grateful for the support of Michigan’s representatives in the U.S. Congress, including U.S. Senator Peters and U.S. Representative Dingell, who are river champions and whose staff have expressed support for exploring opportunities to protect the Huron River.