A healthy river system isn’t static. The flow of a river changes dramatically over the course of a year. The tremendous energy of the spring freshet or a flood event will move boulders, rocks, and sediment to rearrange pools, riffles, and runs to new configurations. A river system like the Connecticut that flows through the soft sediment laid down over thousands of years meanders and moves around its floodplain. A healthy river system is dynamic and dramatic, and many river critters have evolved to live amidst this energy and change.

One of those river critters is the bank swallow, whose Latin name of Riparia riparia doubles down on this fellow’s connection to rivers. Avid birders living in southern New England may have followed the dramatic late summer murmuration of the tree swallows that congregate by the hundreds of thousands in the river’s estuary to rest and feed before their southern migration. This murmuration has been celebrated by Roger Tory Peterson as one of the most dramatic natural events he ever experienced.

The bank swallow does not attend that particular avian party in the Connecticut River’s estuary. Riparia riparia is also a social species that nests in colonies they seem to prefer smaller and less dramatic but still noticeable gatherings a bit farther upstream on the Connecticut River.

I spend a lot of time on the Connecticut River north of my home in Holyoke, Massachusetts, including many special trips along the stretch between Lemington, Vermont and Lancaster, New Hampshire. This stretch includes many miles of meanders north of the reaches impounded by hydropower dams. There are many places along the entire river to spot bank swallows, but I have had wonderful visits with these tiny birds in this reach. The gradual bends and turns of the meanders are great places to spot bank swallows. The eroding banks created by energy of water moving around the meander curves exposes the soft and friable alluvium that makes the Connecticut River valley soils so productive. It is easy to spot the dozens of small entrance holes to the bank swallow nests as you round a corner. And while the outside of river bends are always eroding, the inside bends usually provide a wonderful beach from which you can sit and watch the aerial ballet. And at certain times of years if you watch the nests carefully you can see the chicks waiting in the doorway for a food delivery from mom (or dad?).

The bank swallows are the smallest species of swallow and have the characteristic angular wing and tail shape of the swallow family with a similar tawny coloration to many of their cousins. They are not as brightly colored as the blue-green of the tree swallow, but they are fetching enough I say. If you have had a chance to stop and watch the bank swallows dart, swoop, dive, and swerve just over the surface of the water you’ve seen these little birds in their glory. Their strength and grace in pursuit of one tiny insect after another is a humbling reminder of the effort these birds make to survive and thrive.

The experts say that the population is healthy, which is good news. Part of the reason for that healthy population is the abundant riverine habitat along the banks of the Connecticut and other alluvial river systems.

That however is a good news / bad news story.

While alluvial river systems like the Connecticut River naturally erode and move and meander around their flood plains, humans have artificially increased bank swallow habitat by cutting down the bankside floodplain forests for agriculture, development, and views. The loss of riparian forests accelerates bank erosion, particularly the loss of the majestic silver maples with root systems able to hold together our friable soils. So while the bank swallows can easily adjust to an eroding bank by digging out a deeper or newer cavity, fixing eroding banks that eat away prime agricultural soils or eventually undermine houses and structures is not an easy fix. A healthy riparian forest allows a river to move at its own pace which creates abundant natural bank swallow habitat while protecting human homes. These little birds with little brains have evolved to succeed with healthy riparian forests.

With our big brains and creativity, we can too.

Here’s to the strength and dynamic energy of the bank swallow, a successful resident of our river valleys. I pay homage to those same characteristics that I see in the many human residents working on behalf of rivers everywhere to make them a better place for everyone and everything.

A version of this blog was first published in the Winter 2024 edition of Estuary, a quarterly magazine for people who care about the Connecticut River; its history, health, and ecology—present and future. Find out how you can subscribe at estuarymagainze. com

What are wetlands? Why are they so important? Here’s what you need to know about wetlands and why they are vital to rivers and your clean water.

1. What are wetlands?

A wetland is a low-lying area of land that is saturated with water, either permanently or seasonally. You can’t really talk about wetlands without streams. Small streams and wetlands are where a multitude of our rivers and lakes originate from. Some are so small they don’t even show up on a map yet these headwaters heavily influence the character and quality of things downstream.

2. Why are wetlands important?

Wetlands play a vital role in improving water quality, controlling floods, providing habitat, and supporting the overall health and function of the ecosystem. Consider this:

- Wetlands are the first line of defense for communities facing severe weather.

- Coastal wetlands physically slow down storms by impeding their path to land and minimize their full force.

- Freshwater wetlands and headwater streams inland act as sponges, absorbing significant amounts of rainwater and runoff before flooding can occur.

3. Why is it important to prioritize restoring and protecting wetlands?

Ensure access to clean water

Healthy wetlands and streams are critical to healthy downstream rivers, lakes, and estuaries. These headwaters have proven especially important because of their significant capacity to store and transform nutrients, specifically nitrogen and phosphorus. Without wetlands absorbing these nutrients, downstream waters would receive elevated amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus that cause nasty algal blooms and low oxygen levels in downstream waters. Protecting and restoring wetlands ensures wildlife and humans who depend on rivers for clean, safe drinking water continue to thrive.

Mitigate Climate Change

The effects of climate change will continue exacerbating extreme weather events, such as fires in California, hurricanes in the Southeast, and drought across the country. Draining wetlands, drying up streams, and paving over floodplains have destroyed the habitats fish, birds, and wildlife need to nest, feed, reproduce, and thrive. Protecting and restoring rivers and their headwaters is the best defense against climate change.

Protect habitats and biodiversity

Small streams and wetlands offer an enormous array of habitat for plant, animal, and microbial life. These small freshwater systems provide shelter, food, and protection from predators as well as spawning sites and nursery areas for fish. In fact, many species depend on small streams and wetlands at some point in their life history. Amphibians such as frogs and salamanders rely heavily on these aquatic systems for some part of their life cycle. While fish such as trout require these cool, small streams for both habitat and spawning sites.

Whether you’re making coffee in the morning, brushing your teeth, or filling up your kids’ water bottles, we all want to be confident that the water flowing from our faucets is safe.

But the water sources for too many Americans are contaminated or at risk:

- A recent news story raised concern about toxins in drinking water supplies and possible links to cancer.

- Los Angeles residents have been cautioned to not drink the water following the catastrophic fires.

- Toxic algae outbreaks – fueled by polluted runoff – have shut down water supplies in places like Toledo, Ohio, and also make playing in rivers and lakes potentially deadly for pets and wildlife.

- Asheville, North Carolina residents were without clean drinking water for nearly two months following Hurricane Helene.

Our nation may be divided on a lot of issues, but one thing we can all agree on is that clean water is a human right and a basic need. No matter who you are or where you live, we all need clean, safe, reliable drinking water. And most of our water comes from rivers.

The affiliate of American Rivers, the American Rivers Action Fund, has been conducting public opinion research to understand how people think about water. The findings show that concerns and support for clean water cuts across party lines and demographics.

The main takeaway? Water is a unifying issue that can bridge divides and bring us together around urgently needed solutions for our rivers and communities.

Voters agree. In 2024, all 23 water-related ballot measures across the country passed, safeguarding clean water for millions.

But we have a lot more work to do.

We must continue investing in river protection and smart water infrastructure to improve water quality and reliability for all Americans. Not only is this good for our health and safety, but investing in clean water creates jobs and stimulates the economy.

In addition, decision-makers must resist efforts by polluters to unravel longstanding, common-sense clean water protections. That’s because prioritizing polluter profits over our clean water will compromise the health of our families and make regular people shoulder the costs.

Pollution isn’t patriotic. Every American deserves clean water and healthy rivers. American Rivers is building a bigger, more inclusive effort for our water and rivers. We hope you will join us.

No matter where you live, you are feeling the impacts of climate change and extreme weather.

Right now, the stakes couldn’t be higher — fires are growing increasingly severe, dangerous floods are threatening communities, drought is putting water, food supplies and our livelihoods at risk, and fish and wildlife are being pushed closer to extinction as their streams dry up.

Rivers give us so much; they support the web of life from providing our drinking water to watering our crops and so much in between. In an era of climate change, communities with clean, healthy, free-flowing rivers will be the ones that thrive. We must ensure that all communities, not just a privileged few, benefit from healthy rivers now and in the decades to come.

To address some frequently asked questions about extreme weather and how it affects our nation’s rivers and your clean water, we put together some important information to know:

How can healthy rivers help prevent catastrophic fire damage?

Protecting and restoring rivers and their watersheds, including forests and headwater meadows, can both decrease the risk of catastrophic fire, and help ensure clean, reliable water supplies.

- In a healthy watershed, rain can soak into the ground and replenish groundwater supplies.

- We can manage fuels (excess vegetation) in a way that is sensitive to river health and fragile ecosystems.

- Fuels management over less than 10% of a watershed can have a significant impact on water supply while simultaneously reducing wildfire risk.

How does protecting a river ensure clean, safe, reliable water?

Most of our drinking water comes from rivers. Healthy rivers and watersheds work as a natural filtration system, cleaning and storing water for nearby communities.

- Pollution and habitat destruction through harmful logging, mining, agriculture or other irresponsible development contaminates water supplies with sediment and toxins. This can increase water treatment costs (and the cost of your water bill) and in extreme cases, impact public health.

- Smart stewardship of public lands is critical to safeguarding clean, reliable water supplies. Forest Service lands are the largest source of municipal water supply in the nation, serving over 60 million people in 3,400 communities in 33 States. Major U.S. cities including Los Angeles, Portland, Denver, and Atlanta rely on water from Forest Service lands.

How can restoring and reconnecting a floodplain protect homes and businesses?

Floodplains (the low-lying areas along a river) are an integral part of healthy rivers, and the first line of defense when it comes to safeguarding a community from flood damage.

- When the water level rises in a flood, that water needs somewhere to go. This is why a river needs room to move across its floodplain. It’s also why we should build smart, and keep homes and businesses out of harm’s way.

- A floodplain can act as a sponge: when a flooding river can move into its floodplain, the water can slow down, get absorbed into the ground, and prevent damage to homes and businesses.

- Paving over floodplains and walling off the river with levees can make flood damage worse in downstream communities.

How helpful are dams?

While dams can provide water storage and hydropower, they can also take a significant toll on a river’s health. Many dams are useful, but some are destructive. We must evaluate dams on an individual basis and weigh their costs and benefits when determining how to manage them, and whether to keep them in place or remove them.

- When it comes to preparing for increasing floods, drought, and fires, different communities will have different needs. There is no “one size fits all” solution. Many communities depend on a balance of traditional infrastructure (such as dams) and natural approaches (such as river restoration). Protecting and restoring free-flowing rivers is always a smart strategy.

- Building a dam doesn’t create “new” water, it simply stores the water that’s available. As drought shrinks reservoirs across the country, we need to increase water conservation and watershed protection to help secure our water supplies.

- There are already hundreds of thousands of dams across our country. We must optimize the operations of existing dams, and remove the ones that no longer make sense.

- Reservoirs also lose a significant amount of water each year through evaporation – in some regions up to 15% of the water is lost each year to evaporation.

How can removing a dam improve public safety?

Outdated, unsafe dams can fail, with devastating consequences to downstream communities. Dams can also harm water quality, and can be drowning hazards.

- Flood protection: Floodwaters can overwhelm aging dams and cause them to fail, taking lives and destroying property as has recently happened. Many dams have exceeded their design life and require costly maintenance or upgrades to remain safe. Taking down an unsafe dam eliminates the risk of catastrophic failure and can improve flood protection.

- Clean water: Dams can encourage the growth of toxic algae, by slowing and warming the water. Toxic algae harms water quality and can be lethal to wildlife and pets. Dam removal can restore a river’s flow and water quality, and help eliminate this public health risk without removing the potential of the river as a drinking water source for local communities.

- Drowning risk: Low-head dams can create a recirculating hydraulic at the base of the dam. These hydraulics can trap and drown and drown swimmers, boaters, and anglers who get too close. There have been more than 1,400 fatalities at low-head dams across the U.S.

Following his inauguration, President Trump issued a number of executive orders focused on climate and energy—actions that could have major impacts on the rivers and clean water that all Americans depend on. President Trump has said he wants our country to have “the cleanest water,” which is why we must prevent any actions that harm our rivers and drinking water sources.

That’s why we need a responsible national energy strategy that is considerate of our water resources. Responsible energy development means meeting the needs of people without damaging the environment that our health and water wealth depend on.

No matter who you are or where you live, we all need clean, safe, reliable drinking water. Most of our country’s water comes from rivers. Public opinion research shows that Republican, Democrat, and Independent voters of all ages and races overwhelmingly support protections for clean water. Clean water is a basic need, a human right, and a nonpartisan issue we can all agree on.

The details and implementation of these executive orders will matter as we pursue the dual goals of energy and water security.

We cannot return to days where polluters were allowed to devastate rural and urban communities and their natural resources. But these executive orders eliminate efforts to safeguard communities from environmental harm, putting their drinking water at risk.

In addition to protecting Americans from pollution, we also need to help families and businesses prepare for increasingly extreme weather. As Asheville, North Carolina and other communities in the Southeast continue to recover from Hurricane Helene, and thousands in Los Angeles are without homes following recent catastrophic fires, we should be bolstering policies to fight climate change and working to strengthen communities in the face of severe floods, droughts, and fires.

Here’s a look at some of the executive orders that could have significant impacts on water and rivers, as well as communities’ ability to have access to and a say over decisions about their rivers:

Declaring a National Energy Emergency executive order:

- Directs agencies to use their authorities under the National Emergencies Act (“NEA”) to speed the development of fossil fuels on federal lands and elsewhere. Using the NEA authorities, agencies may use emergency regulations and waivers under the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act and eminent domain to fast-track energy projects, including hazardous materials, pipelines, fossil fuels extraction, and hydropower dams, lessening protections for free-flowing rivers risking increased watershed impairment from leaks, spills, and industrial accidents while further exacerbating the climate crisis.

Unleashing American Energy executive order:

- Establishes the policy of the United States “to encourage energy exploration and production on Federal lands and waters.” Under this order, agencies are tasked with identifying “burdensome regulations” and implementing action plans to address these burdens. In many cases, regulations that may slow down project development also serve to protect communities from the impacts of energy development. Fast-tracking permitting for oil, natural gas, coal, hydropower, biofuels, critical minerals, and/or nuclear energy can leave public health and environmental protections behind. This order also undoes appliance efficiency policies. Securing enough water quantity is a significant problem for many communities, particularly in the West, and this new policy could further deplete rivers of their waters.

Putting America First In International Environmental Agreements executive order:

- Withdraws the United States from the Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The 2015 Paris Agreement is a voluntary global climate accord agreed to by almost all countries to progressively reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Climate change impacts water quality, water quantity and severity of catastrophic floods, droughts, and fires.

Rescinding of Executive Order 14030 Climate-Related Financial Risk

- Revokes the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard (FFRMS). The FFRMS was developed to improve the resilience of communities and federal assets from flooding. It addressed flood risk and limited flood damages by focusing on the protection and restoration of wetlands in addition to the recognition of an expanded floodplain at risk of future flooding. Without the FFRMS in place, communities nationwide will be less prepared and more vulnerable to hazardous weather.

Rescinding of Executive Order 14094 Modernizing Regulatory Review

- Will reduce opportunities for public participation in regulations and meetings with decision-makers, particularly for underserved communities.

Rescinding of Executive Order 14096, Revitalizing Our Nation’s Commitment to Environmental Justice for All

- Eliminates the government-wide approach to environmental justice and equitable access to nature for all communities.

Executive orders impacting specific rivers:

- Certain executive orders have a direct impact on individual rivers, including the San Joaquin, Sacramento, Rio Grande and the rivers of Alaska. In California, agencies are directed to route more water out of the rivers. In the Rio Grande, border wall construction could impact water flow and flooding. In Alaska, thousands of miles of rivers in the Tongass National Forest could lose protections.

Water is a shared resource, and all life depends on healthy rivers. For more than 50 years, American Rivers has been successful in bringing people together for river and water solutions. We remain committed to working with our elected leaders to ensure that this shared resource is protected. American Rivers and our affiliate, the American Rivers Action Fund have a blueprint for the Trump administration and Congress, which includes proactive steps to protect clean water and rivers.

Read the blueprint and voice your support.

The water challenges facing the Southwest are no secret. Frequent local and national headlines highlight the challenges facing the Colorado River, and the Rio Grande has long been the subject of concern across its 1,885-mile journey. Closer to home, communities along the Rio Grande and Colorado River are experiencing drier soils, shrinking rivers, invasive species, and disconnected floodplains. The ecosystems that make up these mighty rivers, including their tributaries, wetlands, and surrounding lands are the backbone of our economies, communities, agriculture, and western lifestyle are at risk. Increasing temperatures, wildly variable precipitation, more frequent wildfires, and greater human demands are pushing these systems to their breaking point.

Congress recognized the challenges these rivers face, and the intrinsic reliance that communities have on their rivers, and took action in 2022 by allocating $4 billion in the Inflation Reduction Act to the Bureau of Reclamation to mitigate the impacts of drought in the Colorado River Basin and other western river basins that experiencing serious disruption and future risk from drought (including the Rio Grande). These federal investments are essential in helping communities manage limited water supplies as well as the increasing threat from wildfires and other natural disasters exacerbated by hotter and drier conditions.

Last week, the Bureau of Reclamation announced over $388 million in funding to support projects in the Upper Colorado River Basin states and over $29 million in the Upper Rio Grande. This infusion of funding will support an array of projects that benefit communities, agriculture, and the environment and represent the type of holistic approach that prioritizes and recognizes the importance of a healthy river system in mitigating the impacts of drought and other natural hazard risks.

In the Colorado River Basin, over $388 million was allocated to over 40 projects in the Upper Basin States of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming through their “Bucket 2 – Ecosystem Restoration” funding. This funding will support projects to restore struggling rivers, streams, forests, and wetlands, mitigating the impacts of drought.

Additionally, Reclamation also announced more than $29 million to mitigate the impacts of drought by supporting water conservation and habitat restoration efforts in the headwaters of the Rio Grande. This investment will ensure greater drought resilience and water security for Colorado’s San Luis Valley and northern New Mexico communities, while significantly enhancing the quality of fish and wildlife habitat in the region.

American Rivers is proud to work closely with a number of applicants on securing these funds including Mesa County Conservation District’s proposal to improve drought resilience on conserved lands by implementing various ecological restoration strategies, like the wetland restoration and floodplain reconnection to reduce sediment and enhance water quality, while promoting habitat restoration for at-risk species like the yellow-billed cuckoo and Gunnison sage-grouse, improving watershed resiliency and aquatic connectivity on the Gunnison and Grand Mesa National Forests and the Colorado River Water Conservation District’s proposal to permanently protect the Shoshone Water Rights in the Upper Colorado River Basin to ensure a reliable water supply for ecosystem, agricultural, municipal, and recreational uses. We were also excited to support many other applications in the Upper Basin. In the Upper Rio Grande, projects in Colorado’s San Luis Valley such as the Teacup Restoration Project will support healthy rivers and wetlands while also improving water management and agricultural resilience. In New Mexico, we are pleased to support projects that mitigate erosion and sedimentation, improve downstream water supply and quality, restore wet meadows, and improve soil health, among other projects.

These investments demonstrate Reclamation’s commitment to mitigating drought and are an excellent first step in acknowledging the importance of healthy rivers, streams, and wetlands in addressing the ongoing water crises in the West. To ensure long-term resilience and sustainability of the Colorado and Rio Grande Basins, durable investments are vital to fully address the challenges these regions are facing today, and will be for the foreseeable future.

Jimmy Carter loved rivers. He grew up fishing as a child in Georgia, and later in life became an avid paddler. As Governor of Georgia, Carter was instrumental in securing protections for the Chattahoochee River. As President, he played a key role in strengthening the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, and securing federal protection for the Chattooga River. Carter also ensured a legacy of healthy, free-flowing rivers by vetoing construction of the harmful Sprewell Bluff Dam on the Flint River in Georgia, and other unnecessary, destructive dams across the country.

In 2018, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, and to highlight President Carter’s leadership and connection to the Chattooga, American Rivers produced the film The Wild President with our partners at NRS.

Below are some quotes from the interview that we did with President Carter for the film, that did not make it into the final production. These words share additional insight on Carter’s connection to rivers and his commitment to their protection:

On his love of fishing:

“I was an avid fisher from my boyhood days…some of the most vivid memories of my childhood is going fishing with my father who was also an excellent fisherman. Back then it was all warm water because we lived in South Georgia. And it wasn’t until I became Governor in the 1970’s that I began to learn about flyfishing on the Chattahoochee River.”

On his values:

“My motivation I think was trying to preserve as much as I could of the beauty of God’s world. Based on my early religious feelings and the heritage that I got from my father and others who would try and do the same thing from a sportsman’s point of view… still, you know, being on a trout stream which is always lovely, the water’s always pure, the environment’s always conducive to preservation or protection, that’s still some of the most awe inspiring experience I’ve ever had.”

On the photo of Bull Sluice Rapid (taken when he was Governor):

“I think people who are explorers and innovators and wildlife experts like Claude Terry [Note: Claude Terry was one of the founders of American Rivers] were a little bit skeptical at first because the Governor actually wanted to ride in the canoe and go down this precipitous falls in the Chattooga River. So, Claude Terry kind of adopted me as one of his students and I learned all I could about handling a canoe and then handling a kayak. And Bull Sluice was a double waterfall, each one was about 5 or 6 feet high, and it precipitated down, and to go down Bull Sluice in an open canoe had never been accomplished. So, Claude and I decided we’d try it. And we actually made it successfully, we only had about 4 inches of freeboard left when we got to the bottom of a thing but that photograph became very famous…since we were the first ones to go down Bull Sluice.”

On vetoing proposals to build harmful dams:

“I vetoed I think 16 different dam projects all over the United States which aroused a great deal of animosity and also condemnation among members of Congress and Chambers of Commerce and so forth. But I tried to maintain as close as I could my commitment that these dams were unnecessary and counterproductive for the future and well- being of American citizens.”

On the power of wild rivers:

“I think that the Chattooga was the first time I ever risked my life, I’d say, in going down a wild river. And I think it gave me an element of both satisfaction and a sense of you might say heroism in confronting the awe- inspiring power of the Chattooga River when I had a major responsibility as a Governor of a state…So I was more deeply immersed in the extreme advantages of wild rivers like the Salmon River which is called the River of No Return as well as those in Alaska and also the Chattooga in Georgia than I ever had before. So, it kind of opened my eyes to a relationship between a human being and a wild river that I had never contemplated before that.”

On his hope for future river protections:

“I think it’s very important for all Americans to take a stand, a positive stand, in protecting wild rivers and scenic areas. I hope that all Americans will join together with me and others who love the outdoors to protect this for our children and our grandchildren.”

The road to recovery is slow after powerful storms like Hurricane Helene and Milton which left devastating destruction across the southeast. As we reel from the lives lost and the sheer scope of the damage, many of us are now also grappling with the new realities of the climate crisis that played out before us in ways few imagined. U.S. Senators and Representatives from the impacted areas — like Rep. Chuck Edwards and Senator Thom Tillis — have been making the case to their colleagues and Congress can no longer delay a significant investment in the recovery process.

The storms’ most apparent impacts were in the shattered homes, damaged roadways, and the extensive loss of property left behind in the immediate aftermath. While the community impacts have been extensive, the storms left a major mark on our rivers as well – which supply drinking water to hundreds of thousands of people and are the backbone of local economies. The immense volume of water altered the path of the rivers, undermined the safety of many of the 1,500 dams in the region, while pulling in unfathomable amounts of structural debris which if left unattended will pose serious long-term threats to drinking water supplies and all of the people and wildlife who depend on our rivers.

Dedicated disaster recovery funding is desperately needed in North Carolina to protect people and restore rivers. With unprecedented hurricane damage ranging from Lake Lure to Asheville and up to Boone, the scope and scale of the debris removal is unprecedented. In many cases, traditional debris removal strategies would be ineffective and environmentally destructive. An investment through AmeriCorps or similar programs within the Department of Labor would create the workforce to address the state’s cleanup needs in an environmentally and economically effective way while also investing in the impacted communities. These activate regional stream debris teams would partner with federal, state, and local agencies to restore rivers like the Green, French Broad, Watauga, and Catawba Rivers in time for spring.

The flood waters took a severe toll on the aging and often unmaintained dams across western North Carolina. Inspections by local, state and federal officials are underway and dozens of dams have been identified as a high threat to public safety. If a major winter storm were to hit the region, it is not likely these compromised dams would be able to withstand the increase in water flows – and the failure of these dams could unleash a deluge that claims more lives and causes more devastation.

The North Carolina dam safety program needs an influx of resources from Congress to assess dam conditions and remove those that are unsafe and unneeded. Additionally, the U.S. Forest Service manages a significant amount of land in the impacted area and they have not yet had the capacity to assess the status or condition of the numerous dams within the boundaries and affecting the Forest Service lands. Regularly inspected and assessed dams are crucial to keeping people safe. The better data we have, the quicker decisions can be made to save lives.

The North Carolina General Assembly will adjourn in short time without any meaningful investments in the recovery of western North Carolina, leaving the federal government as the only option for relief funding to help our state recover in an ecologically and economically resilient manner.

A coalition of 132 organizations and businesses including public health professionals, community associations, think tanks, land trusts, floodplain managers, conservation districts, waterkeepers, rural voices, farm workers, and more, called on Congress to invest in the restoration of our rivers and communities through the passage of an emergency supplemental appropriations bill before Congress adjourns. This legislation must include enhanced public safety, restoration, and infrastructure to help our communities rebuild.

The opportunity to invest in restoring our storm-damaged rivers and in removing failing infrastructure cannot be missed.

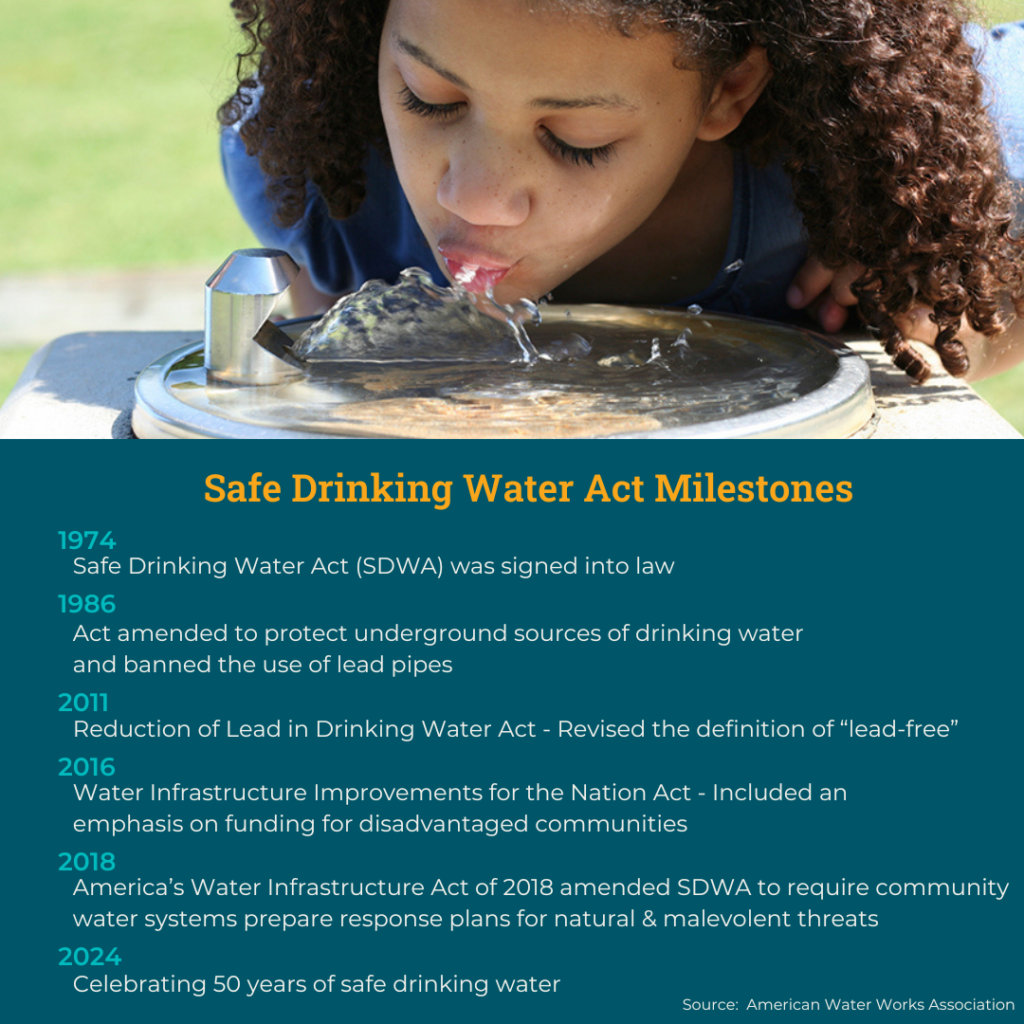

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) is celebrating 50 years! The act was signed into law in 1974 to protect public health by enforcing national standards for drinking water quality. Clean water is a basic human right and is essential to all life.

Fun fact: more than half the country gets its drinking water from rivers!

Below are some notable milestones since the SDWA was signed:

Even still, American clean water supplies are becoming increasingly stretched each year—the pressures of rising population, agricultural and energy demands, and the growing effects of climate change all have a major impact on rivers and water resources. Communities across the nation are without access to safe, clean drinking water. Most recently, Hurricane Helene devastated the Southeast and left millions without clean water for weeks. If we do not embrace innovative solutions, delivering clean drinking water will become more and more difficult.

We must continue to safeguard the clean water that is the lifeblood of our communities and environment. Below are ways to learn more and get involved to help ensure our clean water is protected for generations to come.

This is a guest blog by Rachel Kelleher.

On September 27, 2024, our lives, as we knew them, were forever changed. Hurricane Helene decimated Western North Carolina, a place I call home. The mountains and rivers in this region have brought me peace and healing while supporting my growth and encouraging my strength to blossom. The landscapes here have shaped me. We are collectively grieving the loss of lives, homes, businesses, and the sanctuary of our rivers as we once knew them, so intimately. When I close my eyes, I can run the Green River Narrows in my mind. Every move, like a dance to the sweet song of homecoming. Forever changed, the Green flows naturally, each move a new sequence to explore, discover, and unlock. There are new landscapes to traverse — a mystery to unfurl.

When the rivers swelled to historic peaks, I was directing a mountain bike festival in Fayetteville, Arkansas. I was enveloped by a feeling of helplessness not being there to help physically. Hurricanehelenewnc.com was born on the side of the highway on my way back home. This webpage was built to support my friends in the Whitewater community who had mobilized a direct action response team in Asheville to help communities and individuals in need. We have developed into Helene Rebuild Collaborative. We allocate resources directly to communities that are underserved, isolated, and cut off. We coordinate a variety of specialized volunteer operations that serve to fill in the gaps of aid provided to our rural communities.

Rainpursuit.org reported 32 inches of rainfall in 72 hours near my home at the Green River Cove in Polk County, Saluda, NC. The sheer volume of water that inundated the landscape was not only incomprehensible but landed with such a devastating force that it forever altered the region and the people who survived. The communication grid broke down and people found themselves disconnected from the outside world. Cell phones didn’t work and no one had power. Flooded rivers and devastated infrastructure isolated communities creating fragmented pockets of people scattered throughout the region, completely cut off. In these isolated communities, basic needs were met by humans coming together to support and share resources – neighbors helping neighbors. The initial response was geared towards primal life-saving efforts, then moved towards basic survival needs of water, food, and shelter.

Energetically toggling between mayhem and mass destruction, chaos and catastrophe, devastation and gratitude. I haven’t even begun to unpack the cacophony of emotions brought on by this disaster and I believe we will need new vocabulary words to encapsulate these feelings. The scene here is post-apocalyptic. Wide-spread wreckage, major sand deposits, destruction, and trash piles scattered everywhere. You are left to confront the dualities of our human experience at every intersection, while your nervous system is stretched to an unfathomable capacity. I imagine that we have evolved to a higher capacity of functioning under high loads of stress because of the direct, focused response required by the magnitude of this historic event.

Living through a disaster chimes you into experiencing more gratitude for the simple things we’ve grown accustomed to taking for granted. Having a safe, warm place to rest your head at night, access to clean water, access to food, and connection to emergency medical services. We’ve been challenged both as individuals and communities by this disaster to rise to the occasion to help and support each other. I now understand directly what it means to be displaced and unable to meet your basic needs. To ask for help from this place of need requires a tremendous amount of vulnerability and courage and is one of the most difficult places I’ve ever found myself in. I’ve seen people soften with compassion as a result of empathetic understanding of these new found hardships. At this time, everyone is reaching out a hand and it’s a beautiful miracle to witness and be a recipient of such kindness. There’s a grand illusion of sorts that serves to divide us and entangle us in fear while our natural pulse is towards connection and community with each other. We have to remember that we can accomplish anything when we work together, set aside our differences, and help support one another in times of need. It’s really quite simple.

The force of the Appalachian people is as strong as the mountains in this region. The landscape is vast, steep, hard, and weathered. Water is abundant here and flows like arteries and veins directly into the heart of Appalachia. We stand together in our strengths, united by this life force, and nothing can bring us down. Our collective pulse is vigorous like the creeks and rivers flowing that provide life to our communities and biota. Each individual, when brought together in community, forms the powerful and steady heartbeat of Appalachia. We will sustain connection with each other while rebuilding and maintain unity throughout these lands as a direct reflection of our American dream. Sometimes, it’s only through a path of destruction and deep turmoil that can shepherd us towards an opportunity to cultivate ripe ground. To forge a new dawn and restore humanity back into deep connection and community.

Rachel lives in Western North Carolina and is an avid mountain biker, whitewater kayaker, and nature lover.

There’s a lot going on in a river in the fall. Flows are changing and the temperature is dropping and there’s a bit of fish whimsy happening. In the October afternoon, as the gloaming comes on, the river margins of the Connecticut and other coastal rivers begin to pop and flash with glints of silver. These are the juvenile American shad who were born in the river a few months back and are soon bound for their journey downstream to the Atlantic.

At times I see hundreds of these little silver fish, just a few inches long, leaping a tiny leap out of the water making it ripple and flash in the low light of dusk. I’m told there’s no reason for the leaps, so I just assume the behavior is the group gearing itself up for the collective journey downstream to the Atlantic and their multi-year stint in the ocean as they mature into adults and prepare to return to their natal river to spawn.

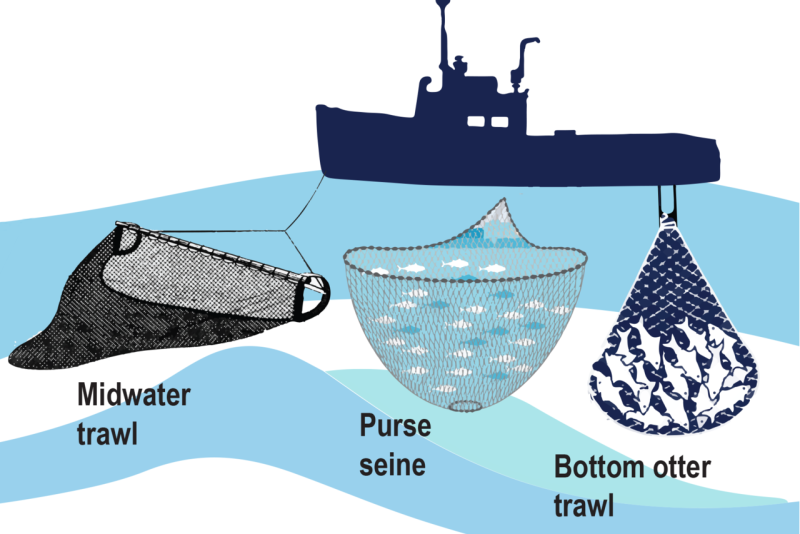

But in southern New England the journey into the Atlantic for these juvenile shad and their river herring colleagues is fraught. For too many years marine fish regulations in the waters off of New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and parts of Massachusetts have allowed overfishing of Atlantic herring. The damage to this ecologically and economically important fishery is a double whammy. Atlantic herring are different from the diadromous alewives, blueback herring, and shad that live in our rivers. But those river herring and shad that are heading out to the Atlantic this month will swim and live amongst the Atlantic herring. That means these river fish also end up in the nets with the Atlantic herring, which are being caught for their use as bait in the lobster industry, for fish oil, or sold as sardines. In regulatory lingo, the river herring and shad that are caught alongside the Atlantic herring are “by-catch.”

Stick with me here, fishing regulations are really complicated. I’m getting to the problem – and the solution!

Marine fishing regulations control amounts, gear, timing, location, and the number of times you can fish in a season. They also try to control by-catch by setting limits on how much non-target fish can be caught. Unfortunately, in southern New England, these regulations have allowed too many Atlantic herring to be caught and too much by-catch of river herring and shad. And the consequences of that have meant dramatically reduced spring returns in our river systems of those 3 and 4-year-old adults. And these reduced returns correspond to the timeframes in which the overharvesting of by-catch was being allowed.

Another way to demonstrate how marine fishing can impact our river herring and shad runs is to look north to the Gulf of Maine where diadromous runs are surging up rivers including those newly opened up due to dam removals and modern fish passage structures. The Gulf of Maine ocean fishing regulations include governing the time and location of Atlantic herring fishing in ways connected to spring migration season. These controls allow river herring and shad time in April, May, and June to head into rivers absent the boats and nets looking for Atlantic herring.

Dropping some regulatory-speak here – that type of regulation is called a time and area control. And American Rivers along with many other conservation organizations, small-scale fishing boats, and state agencies are working to re-establish time and area regulations in southern New England that will allow for a sustainable Atlantic herring fishery as well as rebounded river herring and shad runs.

So where’s that flash of hope?

In late September the New England Fishery Management Council took action to dramatically limit the Atlantic herring fishery due to overfishing, a limit that will effectively close the fishery. This will help to protect the river herring and shad returns for now.

The longer term work of the Council and other fishery managers is to continue developing the basis to reinstate time and area limitations as well as appropriate limits on by-catch in the waters of southern New England.

That work is a few years off and will undoubtedly be fought again by some of the commercial fishing interests. American Rivers will be there along the way with our many partners, scientists, and fishers to ensure our work to remove dams and reconnect thousands of miles of habitat for migratory fish is not for naught.

Want to dive into this issue? The New England Fishery Management Council has a lot of good information on this recent action. Forewarned for the novice – there’s more acronyms and statistics than you can imagine so gear up if you are going in!

Here’s some good general info on Atlantic herring and river herring and their fellow Alosine, the American shad

Our colleagues at the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership have a good website on the issue of forage fish and their connection to sportfishing that includes really great video.

Hand-thinning: The manual removal of vegetation in forested areas to prevent the spread and intensification of wildfire.

Mastication: The use of several different types of equipment to grind, chip, or break apart fuels such as brush, small trees and slash into small pieces.

Prescribed fire: A planned fire intentionally set by land managers to achieve management objectives such as wildfire mitigation or restoration.

These terms may be unfamiliar. In the Yuba River watershed, we are using these methods alongside our partners to manage the forests of the Sierra Nevada and create climate resilience, enhance public safety, and most relevantly to the name and mission of American Rivers, protect river health by reducing wildfire risk. The Hoyt-Purdon Prescribed Fire and Fuel Reduction Project will treat 570 acres within a 918-acre project area along the South Yuba River at a strategic location between the river and surrounding local rural communities. The project will use a combination of the approaches described above to reduce the risk of wildfire and increase forest and watershed resilience. The essential design will reduce the horizontal and vertical continuity of fuels (e.g. make it so fire can’t carry along the ground horizontally or get into the tops of trees vertically) to make it easier to fight a fire should it occur. The project is also designed to protect ecological function and sensitive species.

Hoyt-Purdon Fuel Reduction and Prescribed Fire Project in California

The Hoyt-Purdon Fuel Reduction and Prescribed Fire Project encompasses 570 acres of private land, extending along approximately two miles of the South Yuba River in Nevada County, California. The project will reduce wildfire risk and impacts for six nearby communities and the Yuba watershed, resulting in multiple watershed, ecological, community, and capacity benefits and will increase the pace of ecologically sound forest management in the long term.

At first glance, it might seem confusing that a river-centric nonprofit is involved in forest management and wildfire mitigation, but the impacts of catastrophic wildfire extend beyond the immediate physical destruction of ecosystems and property, and the release of smoke, having severe consequences for the headwaters of California’s rivers. High-severity fires burn vegetation and can even burns soils, preventing regrowth. This lack of vegetation eliminates cover and shade, which raises water temperatures for aquatic species and leads to less dissolved oxygen in the water, a key parameter for healthy aquatic ecosystems. Loss of vegetative cover also prevents precipitation from infiltrating the soil and leads to erosion, releasing sediment downstream and impacting key life-cycle processes such as spawning. On a community level, excessive sediment can disrupt the operations of key infrastructure such as water treatment plants and hydropower production, and if a fire is severe enough, erosion can even reduce the capacity of reservoirs downstream as they receive sediment and debris post-fire.

Fire has always been a part of the ecology of California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range, whether naturally ignited burns that arise from events like lightning strikes, or the prescribed burns by the Tribes that have lived in, cultivated, and stewarded the watershed since time immemorial. But a pattern of Euro-American fire-suppression that began in the 19th century has allowed fuels to build to dangerous levels across the range, putting communities and watersheds at risk from catastrophic high-severity wildfire. This is true of current conditions along the South Yuba River. The Hoyt-Purdon Project aims to address this by first implementing hand and mechanical thinning (i.e. mastication) to reduce vegetation to levels that allow for the safe reintroduction of fire. The project will then implement initial prescribed burning, with a plan to reburn the project area at regular intervals to maintain lower fire risk conditions. As temperatures climb with a changing climate, leading to hotter and drier summers and increasingly risky fire conditions, this work is more important than ever and needs to be scaled.

American Rivers is working to pursue integrated forest and watershed restoration in the California headwaters, recognizing the important role the surrounding landscape plays in protecting and maintaining downstream rivers. The Hoyt-Purdon Project will provide wildfire risk reduction at a strategic location between the South Yuba Canyon and adjacent communities including Nevada City and Grass Valley, thereby protecting both communities and the forested ecosystems that the South Yuba River needs to thrive. American Rivers and partners initiated project activities in spring 2024 and have completed significant hand and mechanical thinning. We plan to conduct initial prescribed burning in fall/winter 2024/2025.

This project and wildfire risk reduction and mitigation across the headwaters of the Sierra Nevada is only possible through strong collaboration. For this project, we are working with three different private landowners, and the project team includes Terra Fuego Resources Foundation, Open Canopy LLC and Stillwater Sciences, with funding from the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Bella Vista Foundation to restore a healthy fire regime to the Yuba River Canyon. Watch the video below to learn more about wildfire risk reduction and the projected impacts on the landscape!