Here in Montana, we like to gamble, as evidenced by the hundreds of small casinos scattered across the state. But we’re gambling with the health of downstream residents by storing decades of industrial waste in the floodplain of the Clark Fork River while we cross our fingers that the next big flood never happens. Tons of industrial toxins could wash down the Clark Fork River. It could happen next year. It could happen ten years from now. It’s not a matter of if the next big flood will happen, but when.

And when we double down on flood risk coupled with industrial toxins, the stakes are just too high.

For over a half-century ending in 2010, the Smurfit-Stone pulp mill along the Clark Fork River near Frenchtown, Montana produced cardboard. Industrial processes to manufacture parts of cardboard boxes left tons of hazardous cancer-causing toxins including heavy metals, PCBs, dioxins, and furans strewn across nearly 1,000 acres next to the river. These toxins have been partially protected from flooding by a decrepit gravel berm separating the mill from the river channel. But a recent berm failure study commissioned by American Rivers and the Clark Fork Coalition predicts a scary re-enactment of the infamous 1908 flood and the toxic waste it swept downstream.

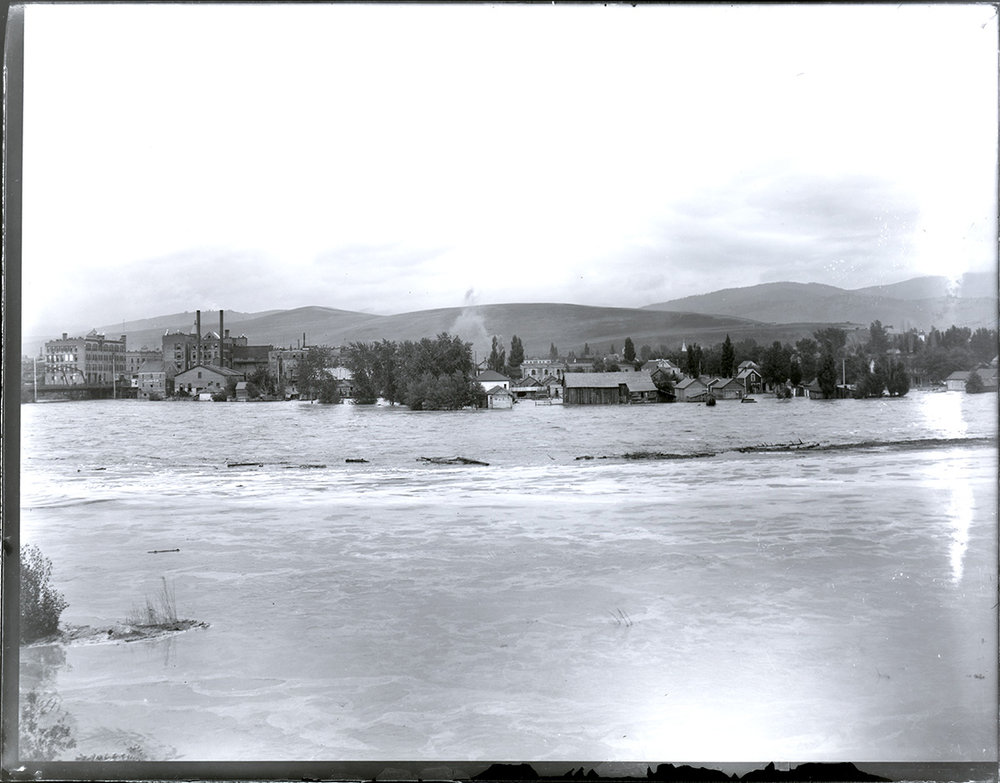

The 1908 flood is the largest on record for the Clark Fork River. It inundated portions of Butte and Missoula, washed out numerous bridges, threatened the then-new Milltown Dam, and dispersed copper mine waste for more than 100 miles. More than a century later, we are still in the midst of grueling, complex efforts to clean up this waste. Sadly, a complete cleanup is simply not possible. Back then, it would have been very difficult to anticipate the catastrophic outcomes of such a large flood, but we know better now.

Let's Stay in Touch!

We’re hard at work in the Northern Rockies for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

Estimating the size of future floods requires extending beyond the historical record, and the use of climate forecasting tools to describe expected changes in local river systems. As climate change continues to tighten its grip on the Northern Rockies region, we can expect a shift in the causes, timing, and frequency of higher flows in western Montana, with less snowfall and more rain. Floods triggered by heavy rain, or rain-on-snow, can raise river levels faster and more unpredictably–just like during the 2022 Yellowstone River flood. The chances of that flood happening in any given year were infinitesimal–less than one-in-a-thousand. Yet it happened less than three decades after back-to-back 100-year floods wreaked havoc on the upper Yellowstone River in the mid-1990s.

We now know that a catastrophic flood on the Clark Fork River would breach the berm at the Smurfit-Stone pulp mill and could deposit industrial waste for miles downstream. While catastrophic flood risk may be small for any given year, that risk compounds over time the longer we wait for a cleanup. The extreme toxicity and persistence of waste at the Smurfit-Stone pulp mill underscores the need to consider flood risk over generations and to avoid leaving waste in place long-term, as has happened elsewhere across Montana.

American Rivers and the Clark Fork Coalition are calling on the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to include the 2024 berm failure report in its risk assessment for the Smurfit-Stone pulp mill. Ensuring that flood risks inform cleanup plans means completely assessing waste stored in – and next to – the floodplain without delay and adopting a cleanup that removes waste, eliminates the berms, and fully restores the floodplain.

At the Smurfit-Stone pulp mill, the consequences of a future flood just aren’t worth the gamble.

Help safeguard the Clark Fork River – Tell the EPA to take flood risks seriously!

Co-authored with: Sam Carlson, Staff Scientist, and Andrew Gorder, Legal & Policy Director, at the Clark Fork Coalition work to protect and restore the Clark Fork River. Together, Clark Fork Coalition, American Rivers, and other partners commissioned the berm failure study from River Design Group, a local engineering firm.

1 response to “Taking a High-Stakes Gamble on Montana’s Clark Fork River”

This article really shows how risky the situation is on Montana’s Clark Fork River. Leaving decades of toxic waste sitting in a floodplain feels like a disaster waiting to happen, especially with flooding becoming more unpredictable. It’s wild that communities downstream are basically forced to gamble on whether the next big flood will spread heavy metals everywhere. Stories like this remind me how ignoring environmental cleanup always comes back to bite us, just like people ignore risks in things like kolkata ff until the stakes suddenly get real.