Black History Month River Reflections: Water and Writers

As the Vice President for People, Justice, and Cultural Affairs, I am committed to exploring the connection between water and Black writers at the intersection of arts, humanities, and environmental justice.

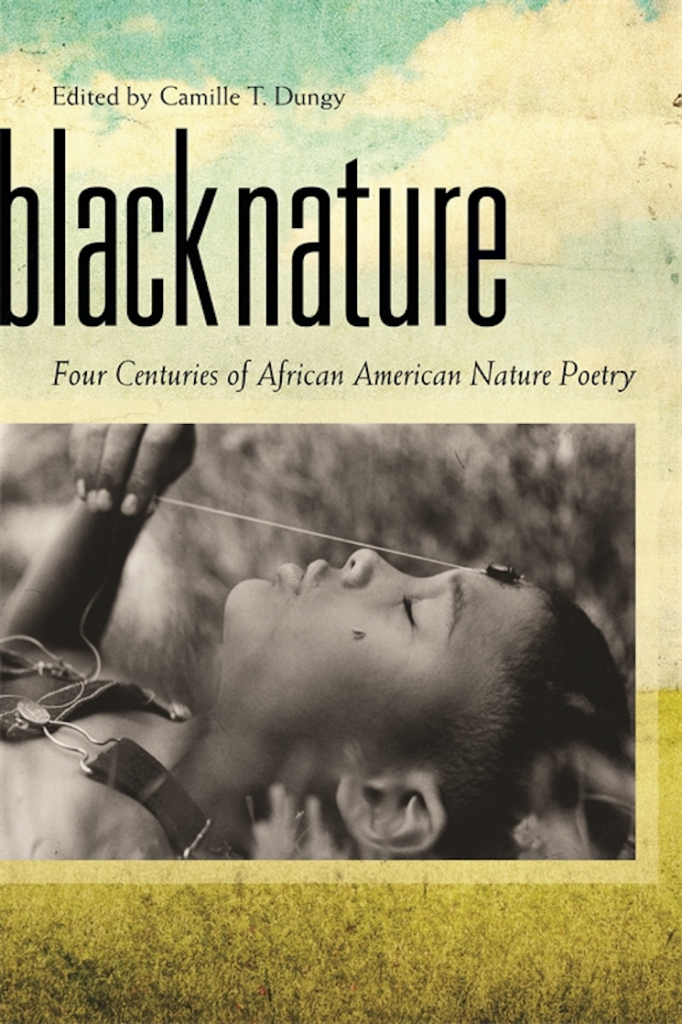

In her anthology Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry, writer and editor Camille T. Dungy sheds a light on nature writing by African American poets; a genre that has not commonly been counted as one in which African American poets have participated. She has noted, “Because of erasures from so many narratives about the great outdoors, the idea that Black people can write out of a personal relationship to nature and have done so since before this nation’s founding comes as a shock to many people.” I’m excited to share the work of “water writers” as I call them, from the Black literary tradition, and illuminate connections between nature and culture. As a multidisciplinary artist and writer myself, I am passionate about telling river and water stories through the genre of nature writing and sharing the works of writers who have influenced me.

Many are familiar with Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes, and may know his poem, The Negro Speaks of Rivers, first published in 1921. Hughes writes of the Mississippi’s “muddy bosom” turning “all golden in the sunset.”

Hughes juxtaposes the Mississippi’s description with regal and ceremonial images and action, including, bathing in the Euphrates, building near the Congo, and looking upon the Nile and her pyramids. This poem elevates and conjures an ancient African regality for the Gulf South’s Mississippi River, and African Americans gazing upon her.

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Hughes begins and ends with, “My soul has grown deep like the rivers.” Mother Mississippi is where my soul grows deep too.

Next, I’m thrilled to highlight the work of the 19th Poet Laureate of the United States (2012-2014), Natasha Trethewey. Like me, she yields from the Gulf Coast and writes about race and relationship through narratives of the river and natural world. Her poem Elegy [“I think by now the river must be thick”] is an elegy for her father, and summons memories of casting and catching. She writes:

All day I kept turning to watch you, how

first you mimed our guide’s casting

then cast your invisible line, slicing the sky

between us; and later, rod in hand, how

The invisible line between them, a color line, becomes invisible as she writes in metaphor about fishing and fathers; a nature writer who invokes cultural and social forces through “water writing.”

Finally, I’ll frame author, anthropologist, and filmmaker Zora Neale Hurston’s work as “water writing.” In Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo, Hurston shares the story of Kossula “Cudjo” Lewis and his community, located where the Mobile River meets the bay, in Plateau, Alabama in 1927.

Hurston relates Kossula’s firsthand account as a survivor of the Clotilda and the community of formerly enslaved Africans said to have been the cargo of this “last slave ship.” In one of her most significant vignettes, Hurston visits this community, situated at the confluence of the Mobile River and Chickasaw Creek, at the mouth of the Bay on a sweltering hot day. Her interview includes the heat and thirst in the cabin, she writes of Kossula’s thirst:

I waited but not a sound. Presently he turned to the man sitting inside the house and said, “Go fetchee me some cool water.” The man took the pail and went down the path between the rows of pole-beans to the well in the daughter-in-law’s yard. He returned and Kossula gulped down a healthy cup-full from a home-made tin cup.

Hurston captured the importance of “cool water” in this passage, allowing readers to experience the swelter, the rustle of pole beans, the metallic clink of the pail, and the relief of the cool water fetched. These cool waters are the site of baptisms in the community, and today, are the sacred waters embracing the remains of the Clotilda.

My hope is that everyone who loves rivers will recognize their cultural significance and celebrate the Black Literary tradition’s nature writing authors. Let us hear the river and water stories of African American writers that claim rivers as spaces of conflict as well as celebration.

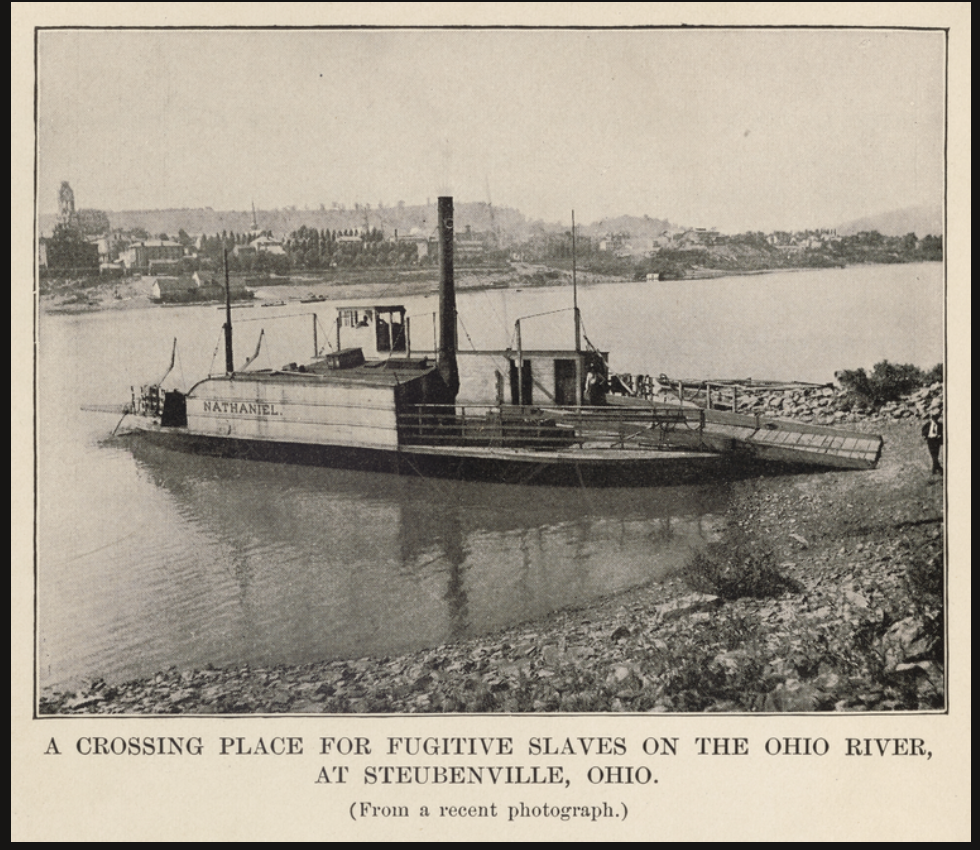

Rivers have been sites of trafficking as well as sites of crossing and emancipation. Rivers have been the sites of lynching and drowning as well as sites of baptism and jubilation.

In his poem, Gwendolyn Brooks: America in the Wintertime, Black Arts Movement poet, author, publisher, and educator Haki R. Madhubuti writes:

you have fought and fought most of the twentieth century

creating an army of poets who learned

and loved language and stories

of complicated rivers, seas, and oceans.

May we all speak the love language of the water writers and commit ourselves to the cause of healthy rivers and clean water for people and nature.

2 responses to “Black History Month River Reflections: Water and Writers”

This is lovely! I’m currently writing a book on this topic. Thank you for writing this!

Wonderful connections, readings, and meditations. Thank you!