Treasures of the Lost Gorge: An Urban River’s Redemption

Work has been done to improve water quality in the Mississippi River Gorge, but dam removal would help improve water quality further while bringing rapids and riverside parkland back to the Twin Cities.

This guest blog from Mike Davis is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Mississippi River Gorge.

“The channel was very crooked, winding about between reefs of solid rock, with an eight to ten mile current… he knew that the drift of a minute in that white water would pile us up on the next reef below… for the next six miles he turned and twisted among the reefs, under a full head of steam, which was necessary to give us steerageway in such a current.”

– From “Old Times on the Upper Mississippi” by George Merrick

Although this does not sound like a description of any river channel within the Twin Cites, Minnesota, it is.

Only a century ago, the reach of the Mississippi River downstream of St. Anthony Falls met this description. Depending on the season, a raging white-water torrent or a more docile rapids and riffle channel flowed around a dozen or more islands on the way to its confluence with the Minnesota River. Early explorers remarked often about the majesty of the falls, and were amazed by the huge numbers of eagles and other fish-eating birds that congregated in the gorge below to feed. This was no accident since the rapids below the falls was one of only three that existed upstream of St. Louis. With the falls blocking further upstream movements, the rapids area of the Mississippi’s only gorge was no doubt a destination for both migratory and resident rock-loving fish species. Although historic accounts lack detail, it is probable that this rapids was a critical spawning habitat for several large river fish species, such as sturgeon and paddlefish. Today the rapids are “lost” beneath the impoundment created by the Ford Dam.

Historically the Mississippi River between St. Anthony Falls and Lake Pepin (68 river miles) supported at least 43 species of native mussels. Native freshwater mussels have been integral players in river ecology for millions of years. Mussels feed on bacteria and fungi that they filter from the river water, stabilize the riverbed with their shells and provide attachment and habitat for other life ranging from algae to walleye. They are unique among the world’s mollusks in having a parasitic life stage using fish as temporary hosts. Numerous fascinating adaptations of females deliver larvae onto the fish species of choice.

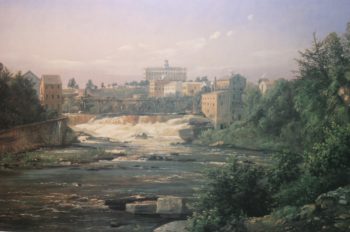

Painting of the Mississippi Gorge | Minnesota Historical Society

Once so abundant that the river bottom was literally made of mussels, by 1900 water quality in this reach of the Mississippi River had declined enough to nearly eliminate them. Giant floating bogs of rotting sewage sucked the life-giving oxygen out of the water for decades. These degraded conditions continued until the 1970s when Congress passed, and President Nixon signed, the Clean Water Act. Water quality improved during the 1980s and 1990s with the separation of sanitary and storm sewers in the Twin Cities Metropolitan area and wastewater treatment was much improved.

Today, both native fish and mussels are again thriving in this reach of the river. However, 20 species of native mussels have yet to recolonize this improved habitat. In order for this to occur, host fish carrying mussel larvae must travel from a part of the river still supporting these species – travel greatly impeded by dams today.

With large river species of fish far below their reported historic abundances and with spawning rapids obliterated elsewhere on the Mississippi below the falls, restoration of these rapids and access to them by migrating fish would be an enormously important ecological achievement. A modern-day redemption for the uses conceived of at the close of the 1800s, but still with us today.

Below the Mississippi Gorge falls | BF Upton

Moreover, with the recent return of good water quality, restoration would create recreational and scenic opportunities not found in a large urban setting anywhere else in the U.S. Redemption of these rapids would create 2 to 300 acres of accessible riparian parklands and 15 miles or more of high quality shoreline angling opportunities.

Kayaking anyone?

You can help us Restore the Gorge! If you are in the area, attend a public meeting:

July 16th at 6PM at Mill City Commons, 704 Second St. S., Minneapolis, MN 55401

July 17th at 6PM at Highland Park Senior High School auditorium, 1015 Snelling Ave S, Saint Paul, MN 55116

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4987/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Author: Mike Davis

Author: Mike Davis

Mike Davis is a River Ecologist.

1 response to “Treasures of the Lost Gorge: An Urban River’s Redemption”

there are already hundreds of rowers, canoe paddlers, and kyakers enjoying the river gorge every day! the dam removal will take out the home for all of us who care about the gorge deeply, and take good care of it daily! Why are you ignore our existence, our love and our daily training in the passage of the river? How often do you come to the river? how often do you get into the river? How much knowledge do you have about the river in the present day? The past is past. The river changes every day. The river never goes back to the old time, old place. It is not science to discard us hundreds of local rowers, paddlers, and kayakers and fishermen who pay local taxes, who love and use and take care of the river gorge every day, and to fantasize and favor about some potential kayakers from distance, who’d just come and make noise and drink and pollute and pad their butts and leave. Who’s going to clean up after them? We the taxpayers. Will the mussels come back? maybe, a big maybe. But the dam removal will definitely expose hundreds of years of toxic sediment, poison the eagles that have just come back from extinction, cranes, foxes, and many other birds, let alone the fish that are flourishing in the pool. The biggest danger, however, is the carp. They’ll have no gate, and migrate freely and happily to the big lakes and the river source.