A Legacy of River Protection and Restoration in the Rappahannock

In Virginia, there is a history of community interest in protecting and restoring the Rappahannock River, but the Rappahannock is now threatened by proposed changes to fracking chemical disclosure laws in the VA General Assembly.

This guest post by Dr. Jason Sellers is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Rappahannock River.

The Rappahannock River has long been a focal point for Virginia’s human communities, and its health remains vital for Virginians today. Although often confident in the resilience of their natural resources, including the Rappahannock, Virginians have historically taken steps to protect the river and the opportunities it provides. Concerted efforts since the 1960s have revitalized the river, its industries, and its people, even as new threats imperil the Rappahannock today.

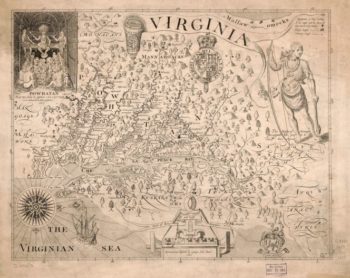

For centuries, anadromous fish runs and fertile soils have attracted Native Americans to Virginia’s river valleys. Algonquian peoples, many of them associated with the Powhatan chiefdom, centered their territories on the major waterways on which they relied for food and travel. John Smith met a number of these groups as he explored the Chesapeake in 1608, including the Rappahannock tribe, whose name means, “the people who live where the water rises and falls,” and from whom the river takes its name. Smith also received reports of Manahoac settlements above the Rappahannock’s fall line.

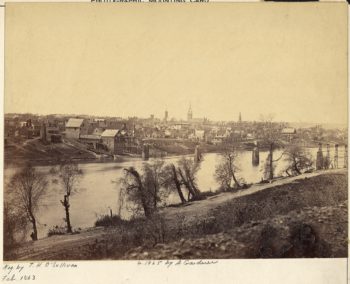

English colonists found Virginia’s rivers attractive for similar reasons, dispersing across plantations on level, fertile land near the waterways that could carry their tobacco and wheat to market. As settlement expanded inland, the House of Burgesses ordered the construction of Fredericksburg in 1728, at the fall line of the Rappahannock. The town was to serve as a distribution center connecting backcountry settlers and the area’s emerging iron industry with Atlantic trade networks. Several years earlier, Governor Alexander Spotswood had established German iron workers on the Rapidan River, the Rappahannock’s largest tributary, and by 1720 Spotswood’s Tubal Furnace was operational, later providing iron for Fredericksburg’s gun manufactories during the American Revolution.

Although the new federal government declined to designate Fredericksburg as a port-of-entry, investors hoping to position the Rappahannock as a regional trade hub constructed an extensive canal system. When the system failed to turn a profit, the Fredericksburg Water Power Company transformed it in 1855, constructing a wooden crib dam to direct water into the canals for water power rather than transportation, and enlivening Fredericksburg’s thriving agricultural and industrial mills. The company modernized this operation in 1910, constructing Embrey Dam to channel water through turbines at its new power plant to provide electricity for the growing region’s industries. The plant ceased operations in the 1960s when power demands exceeded what local water power could supply, but the canal system continued to provide raw water for the city into the early 2000s.

By the turn of the 21st century, intensive agricultural and industrial development had been shaping the Rappahannock for three centuries, and a major dam had obstructed it for over 150 years. As early as 1759, upstream residents complained that mills obstructed fish runs, and the General Assembly ordered mill owners to build fishways through or around their dams — an early example of political action to protect valuable marine species. The watershed’s extensive timbering and mining had less obvious but equally damaging effects on the river’s health, the former removing ground cover and eroding the banks of the river and its tributaries, the latter leaving open slag piles to leach into streams. To protect and manage the valuable fisheries on the Rappahannock and throughout the commonwealth, the state tasked a series of agencies with regulating its finfish and shellfish industries beginning in the 1870s. Similar concerns about industrial pollution, as well as municipal wastewater discharge, led to one of the nation’s first water control laws in 1946 to protect municipal water sources.

Virginia thus had a long history of environmental protections by the time the General Assembly created the Virginia Outdoor Recreation Study Commission in 1964 amid a mounting environmental movement. Anticipating that the mix of counties, cities, and towns comprising Virginia’s metropolitan areas would complicate land-use planning, the Commission’s 1965 report called for regional planning and action when multiple localities shared a resource, identifying waterways and river basins as particular concerns. That report and the 1966 Virginia Outdoors Plan became the underpinning for subsequent legislation that created an open-space easement program designed to protect watersheds, scenic views, historic landscapes, and wildlife habitats by permanently removing land from development. Since 1988, more than forty organizations have secured over 500,000 total acres of perpetual easements in the state.

Such easements constitute one crucial tool for regional conservation efforts on the Rappahannock River. As part of a larger flood control and water supply project, the City of Fredericksburg purchased 4800 acres of forested riparian lands along 32 miles of the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers in 1969, later converting more than 4000 acres into a conservation easement in 2006. Residents along the river have responded to environmental concerns as well, some formalizing their efforts by founding the Friends of the Rappahannock (FOR) in 1985. Besides securing its own property and establishing additional conservation easements, FOR has been instrumental in raising environmental awareness by combining a range of educational and restoration programs throughout the watershed with political advocacy on behalf of the river and its residents. As co-founder Bill Micks explained in 2017, “Almost everybody from top to bottom on this river now realizes the importance of a green 100-foot buffer or 200-foot buffer and how important that is for water quality. I think things have really taken a step in a good direction.”

Perhaps the most visible moment in the Rappahannock’s recovery came with the removal of Embrey Dam. Concerns about declining migratory fish stocks and the poor condition of the dam dovetailed with desires to restore the river and boost tourism, and local officials and conservationists cooperated to secure congressional support. A 1998 federal study determined that fish passage and the restoration of the Rappahannock was in the public interest, qualifying the dam removal project for federal funding. After removing 250,000 cubic yards of accumulated sediment, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers used explosives to breach the dam in 2004, removing the rest in 2005 to restore a free-flowing Rappahannock for the first time in 150 years.

The outcome of years of coordinated efforts between the state, the city of Fredericksburg, federal agencies, the military, and non-profit organizations, the removal of Embrey Dam is a reminder of both the challenges and possibilities inherent in protecting regional watersheds like the Rappahannock from new threats like fracking. Remembering events of the early 2000s, Chief Anne Richardson of the Rappahannock Indians recalls, “We had a tradition of pouring salt in the water to cleanse and so we went and poured salt in the water and prayed that the creator would come because he created this river, it belongs to him, not us. And so we asked for purification and healing and he did it.”

Through the efforts of the citizens and governments it serves, the Rappahannock today is the longest free-flowing river in Virginia. The last decade has seen migratory fish returning to the river’s upper reaches, oyster populations rebounding in the tidal estuary, the river’s banks revegetated, bald eagle nesting sites multiplying, residents and tourists boating and hiking, and a cleaner water supply for the region’s inhabitants. Centuries ago and today, from the mountains to the bay, a healthy Rappahannock remains a center of Virginia life.

FOR THREE YEARS IN A ROW, the Virginia General Assembly has rejected industry attempts to roll back important fracking chemical disclosure rules that would apply to natural gas development in the Rappahannock River Basin. This idea, to keep chemical secrets from the public, continues to rear its ugly head. Despite defeating these bills in past Virginia General Assembly sessions, there is currently another legislative attempt to erode these protections sitting in a subcommittee of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Council and may end up in the Virginia General Assembly for a FOURTH YEAR IN A ROW. This is unacceptable.

[su_button url=”https://salsa4.salsalabs.com/o/50930/p/dia/action4/common/public/?action_KEY=25010″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Dr. Jason Sellers is a professor of history at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, VA. He is a cultural and environmental historian of 17th-and 18th-century North America interested in landscapes and bodies, and is currently working on a project that explores the interactions of Munsee Indians and European colonists in the 17th-century Hudson Valley.

1 response to “A Legacy of River Protection and Restoration in the Rappahannock”

The threat of fracking on the Rappahannock is so bad that it is now rated #5 Most Endangered River in the USA. It is either ironic or hypocritical that FOR opposes fracking – but does not oppose the specific allowance of fracking in conservation easements right across the river from the Rappahannock National Wildlife Refuge, in the most pristine stretch of the Rappahannock.

One conservation easement allows an astonishing 88 oil wells and 24 gas wells! Another allows “subsurface extraction of oil and gas” in the pristine marsh right across from Fones Cliffs! Perhaps the most astonishing is the case of the first conservation easement in Essex County: the original 1977 easement did not reference oil and gas; incredibly, it was amended twice in 2010 to specifically allow oil and gas exploration and extraction.

Why does FOR “look the other way?” Is it because those landowners provide financial and other support to FOR? FOR must address the three conservation easements that allow fracking, even if those landowners donate money to FOR. Otherwise, the Rappahannock will continue to be ranked the 5th Most Endangered River in the USA because of the threat of fracking.