New Safety Measures Needed to Protect Montana’s Flathead

Oil train derailment could ruin pristine Middle Fork Flathead River, join us in urging the Federal Railroad Administration to develop safety guidelines and agreements.

This guest blog by Jack Stanford is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Middle Fork Flathead River.

When I came to the Flathead in 1971 to begin work at the University of Montana’s Flathead Lake Biological Station, I was stunned by the clarity and purity of Flathead Lake. All these years later, water quality in the lake remains largely pristine; indeed, it is the cleanest large lake in the world with significant human population in the watershed. That is largely because almost all of the inflowing water comes from Glacier National Park and surrounding wilderness, and people have taken care to minimize pollution through adherence to forestry best management guidelines, floodplain protection, and effective treatment of urban sewage.

However, one thing that has stayed the same for years is the presence of the railroad and highway corridor along the Middle Fork Flathead River and on past Whitefish Lake. In the early years, most of the commercial hauling involved materials that were fairly innocuous if spilled into the rivers. Wrecks inevitably occurred. I’ve seen several over the years: lumber, grain, TV,s and other goods floating down the river from train derailments and a couple of small petroleum spills from truck wrecks.

Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) says the rail line is as modern and safe as it can be given the terrain it follows through this mountainous river corridor. However, a good share of the rail traffic these days involves long trains composed of 80 to 100 or more tank cars full of petroleum products, including crude oil. Actually, BNSF does not say exactly what’s in the tankers because they are not required to do so. Nor do they have a publicized, robust plan for prevention, much less, what to do if a huge spill does occur.

Let’s say a derailment happens in Nyack, Montana — several huge tankers brake open and thousands of gallons of crude oil spill into the river. It would be a toxic mess beyond comprehension, going rapidly downstream and penetrating into the alluvial aquifers killing everything in its path that cannot somehow get out of the way.

Oil would be in Flathead Lake within hours.

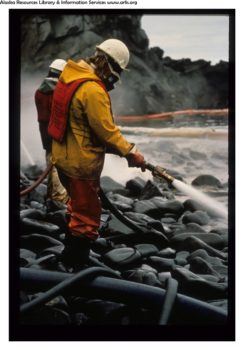

A worker assists in the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill cleanup in the Prince William Sound September 11, 1989. | Photo: ARLIS Reference

Even if soaker booms were deployed in time to be ahead of the plume, they would only capture some of the heavy stuff, while the volatile and soluble pollution would escape into our environment where it will persist for decades (think Prince William Sound – the Exxon Valdez spill impacts remain prevalent in that ecosystem 28 years later).

Crude oil and processed fuels contain a wide variety of pollutants including, for example, benzene and PCBs that are extremely toxic in high doses and cause cancer and other health issues, even in extremely low doses. Scientists at the Biological Station have monitored small truck spills around the lake in the past, and the pollution was measurable for years even though enormously expensive restoration was implemented. Suffice to say that our lives in the Flathead will never be the same if a major railroad oil spill occurs in our ecosystem.

What can be done to prevent a disaster?

Well, it has to start with BNSF recognizing that a major spill simply cannot happen. Our water, our national park, our rivers, and our lake are priceless.

No amount of post-spill payoffs or restorations will repair the damage. I and others have repeatedly called for serious, comprehensive consultations with BNSF, civil authorities, land and water management agencies, and the public on preventive measures. It starts with complete transparency on track and train monitoring, along with complete clarity on what is in the tankers for every train that passes through our watershed (the same should apply to tank trucks on the highways).

Next, stringent safety measures must be developed and implemented, such as speed limits and additional snow sheds to protect the track from avalanches. Of course, planned and practiced actions for response if a derailment does occur are also important, but effective safety measures to make a worst case scenario derailment, spill, explosion, and fire as unlikely as possible are absolutely essential. Response actions have to take into account the wide array of chemicals involved and detailed knowledge on how those chemicals mobilize in the environment. Consultation will raise other issues.

The bottom line is to think the unthinkable. It could happen. We need to minimize the chance and be ready if and when it does occur so that the impact is minimized. Thousands of people just found out what “worst case scenario” means in Houston. Let’s not let a worst case scenario happen here.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/705/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Jack Stanford is Director Emeritus of the University of Montana’s Flathead Lake Biological Station.

1 response to “New Safety Measures Needed to Protect Montana’s Flathead”

I want the Federal Railroad Administration to protect the Middle Fork Flathead by developing a safety agreement with Burlington Santa Fe that helps prevent train derailments.