Finding the Flint: A Bold Vision for Restoring Urban Headwaters

A group of local activists and organizations are working together to restore the Flint River’s urban headwaters for the benefit of the local community and the river system downstream

Georgia’s Flint River: I grew up just one watershed away, and with friends I paddled nearly the whole navigable length of the river in the summer of 2003. But as for the river’s source, until I started working on the Flint six years ago, I’d always just taken as a given what I’d always heard as I was coming up in the river community in Georgia. And what I’d always heard was a sardonic line invariably delivered with a sad shake of the head or maybe a sarcastic chuckle:

“You know, the Flint starts at the airport.”

Minus the exceptional presence of a major international airport in the description, it was the kind of line we hear often about urban streams. Its utterance is a way for river-lovers to grapple with the concept that some streams may seem so degraded as to be past the point of no return. But that attitude threatens to write these streams off. And in the case of the Flint, it threatened to write off the very source of the river.

The author examining the headwaters. Photo credit to: Hannah Palmer.

So one blazing hot day in July six years ago, after doing just a little homework with aerial photos and topographic maps, my colleague Jenny Hoffner and I set out for a day of urban exploring to find the source of the river for ourselves.

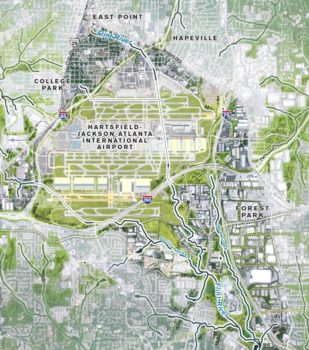

We saw what a few other brave souls – or at least hydrologically savvy folks – already knew: The Flint doesn’t quite start at the airport. It starts with a few urban streams emerging from storm sewers and culverts in the communities just north of the airport. These streams come down off of ridges in the cities of East Point, College Park and Hapeville – originally railroad towns that have become a part of the sprawl of Metropolitan Atlanta and have been re-shaped by its booming international airport in recent decades.

The creeks come down off of the ridges that still carry the railroads today. These urban streams run in and out of culverts, under roads and parking lots, behind buildings and through undeveloped lots, and they join together to flow under the airport in pipes about a mile and a half long. Coming out the downstream side is a stream large enough to start earning the name “river” as it flows southward through the rest of Georgia.

A History Hidden in Road Signs

Along the way in this exploration, I found a U.S. Geological Survey topography map dated 1895 that shows many more little tributary streams throughout the headwaters than you can find in the landscape today: most of them over time have been converted into typical urban storm sewer infrastructure. But even in today’s landscape, there are plain-as-day clues to the river’s role in the history of the area, if you’re looking for them.

The beginning of the Flint River isn’t actually the airport.

For instance, a little dead-end street at the edge of airport property is called Terrell Mill Road. A few minutes south of there, you come across Lee’s Mill Road, where trucks now haul trash to a landfill and rocks out of a quarry. Both of these road names refer to the water-powered grist mills that were central to the communities in the area long before airfields were ever contemplated.

All of these ironies stand out because the Flint River is Georgia’s second-longest waterway, and it’s a critical water source for human and non-human Georgians across the state. It is one of the longest free-flowing rivers in the country and home to unique biodiversity, but it toils under the strains of land development and water use for much of its length.

Teaming Up to Restore a River

Since 2013, I’ve had the honor to convene water utilities and environmentalists in the Upper Flint River Working Group – a collaborative forum for finding ways to restore drought resilience to the entire upper Flint River basin and the communities that depend on it. For four years now, we at American Rivers have collaborated with Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport to identify opportunities for green stormwater infrastructure – not on the runways, but along roads, parking lots, and landscaped areas across the airport’s 4,700 acres – where we can do a better job of infiltrating rainwater into the ground rather than letting it rush quickly downstream.

In 2017, American Rivers, The Conservation Fund and the Atlanta Regional Commission launched Finding the Flint, an effort to support the health of the Flint while reconnecting people to the hidden river. These groups worked with Sixpitch, a design firm founded by Atlanta BeltLine visionary Ryan Gravel, in partnership with Hannah Palmer, author of Flight Path: A Search for Roots beneath the World’s Busiest Airport, a book about urban planning and history in area, with a big focus on how the airport changed the region.

Finding the Flint is an ambitious vision. It incorporates strategies for bringing the river to the forefront in a landscape where the airport, interstate highways and urban development loom large. These approaches range from facilitating more urban exploring to using the Flint as a focal point in future airport and airport-area plans and improvements. Sixpitch analyzed several areas around the airport where the piped Flint River could be unearthed and restored, and where inviting green spaces could make the area around the airport destinations in themselves, rather than places to pass through in order to get somewhere else. The primary goal of Finding the Flint is putting the Flint River back on the map.

Where We Go From Here

How do we turn this vision into reality? By introducing the vision to partners of all kinds who have a role to play in airport-area redevelopment, who want to join in for ambitious urban watershed restoration in metro Atlanta, and who want to see authentic urban development that connects communities to one another and to their own intrinsic natural assets. Hannah Palmer now serves as Coordinator for Finding the Flint, a role that includes creating and shepherding the Finding the Flint Working Group, a big-and-getting-bigger task force of stakeholders and “doers” from local governments, the airport, corporations, community groups and elsewhere.

The Flint headwaters. Photo Credit to Hannah Palmer

The level of enthusiasm for this vision from all quarters and from local residents throughout the area has been staggering. Working Group participants include representatives from Atlanta’s airport, Delta Airlines, the cities of East Point, Hapeville and College Park, Clayton County Water Authority, Flint Riverkeeper, the Metro Atlanta Urban Farm, Woodward Academy and many more.

The environmental justice organization ECO-Action and the Atlanta-based Partnership for Southern Equity have become key partners in Finding the Flint, and their perspectives provide a necessary ingredient to the project: an educated eye for equity, justice and an improved quality of life for all as the area sees re-development and greener urban infrastructure. This year, Flint headwaters residents have taken part in the Atlanta Watershed Learning Network, an advocate training course that helps residents develop the tools to influence urban development plans with an awareness of green gentrification and affordability concerns, for the benefit of those who live there now and for decades into the future.

Restoration Starts at the Source

What these partners are building is the opposite of the sad joke I used to always hear about the source of the Flint. They understand that restoring a river’s health starts at the source.

As Finding the Flint takes off (pun intended), we’re excited to be at the forefront of a new vision for the world’s busiest airport and its neighboring communities. Central to this vision are local people, local businesses, and the local environment. Being a steward of the highly contested Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint river basin is a big responsibility for Atlanta, and as this effort continues to be realized, as more partners buy into the idea and start implementing projects big and small, the Flint River will come to serve as a focal point for a world-class airport that prioritizes urban planning, resilient natural resources and community cohesion.

Then, perhaps, the Flint River will find its way back on the map.

1 response to “Finding the Flint: A Bold Vision for Restoring Urban Headwaters”

Hi. I grew up where the airport is now, and played along the Flint River (ew) as a child in another home. I was happily surprised to see this. But I moved away to Northern California a while back. I was looking up rivers. I’m still shaking my head wow. Good for you man!