The birds and the bees is a well-known shorthand response to a child’s inquiry about reproduction. Adults have long noted that a bird laying an egg or a bee collecting pollen show examples in nature for how new life comes along.

But the fish and the flowers?

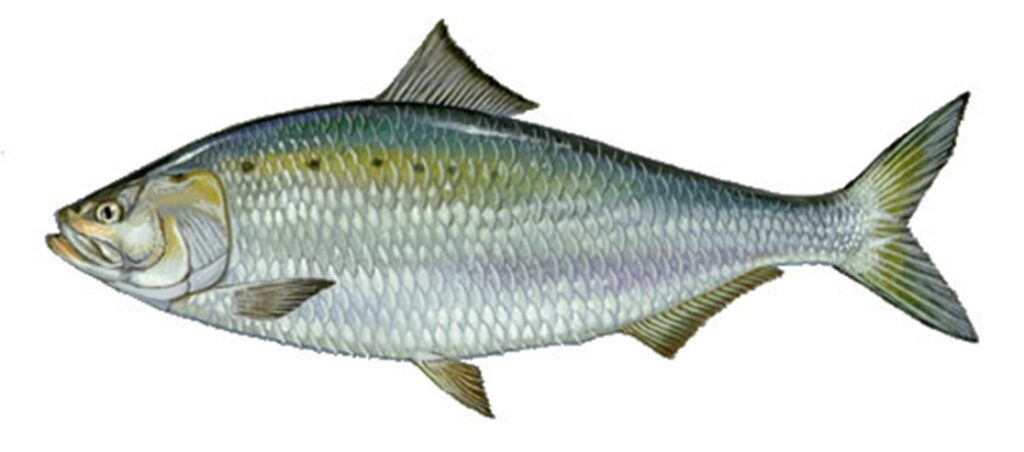

Along the northeast coast as spring weather is rolling on one of the earliest blooming trees is what many call the shadbush (Amelanchier arborea) a lovely deciduous tree that produces edible berries. The name shadbush, or as some say shadblow, is attributed to the fact that people noticed that the flowering of this tree corresponded to the annual spring migrations of American shad (Alosa sapidissima). Shad are a very tasty fish whose early spring runs were avidly waited following a long winter of relying on stored food by indigenous peoples as well as colonial settlers. Shad were also long used as fertilizer, being buried alongside seeds planted in the spring soil.

People have long used a variety of natural cues to help them understand or anticipate how their environment might provide for them. Today we have more cues and data that are much stronger predictors of coming events that help to confirm or clarify these traditional environmental signals. So while we know that trees leaf out and flower in response to both increasing daylight and temperatures, fish also respond to temperatures. For the migration of American shad, the principal cue is water temperature. When river temperature hits 50 to 55 degrees Fahrenheit shad will begin to swim upstream after congregating nearshore at the outlet of coastal rivers. The migration typically runs from mid-April to June. And as the shad runs taper off the shadbush fruits emerge and add an early season sweet complement to the nutrient and protein rich shad.

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Northeast for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

And you have no doubt already come to the thought that if temperature is an important cue to shad migration, what does climate change mean for them and our work to rebuild populations to the millions that our ancestors saw? Increasing temperatures are expected to shorten the duration of the run as spring temperatures rise earlier and faster. Less obvious is the impact of warmer water on reproductive success.

Their work to ascend tens or hundreds of miles up freshwater rivers to spawn consumes energy during a time when these fish are not feeding. Swimming through warmer water in both the ocean and rivers, and working hard to make it past dams burns calories that would otherwise be devoted to producing roe (eggs) or milt (sperm), reducing reproductive success. Shad are repeat spawners (or what the scientists call iteroparity) meaning they will migrate up and down river systems several times throughout their lifecycle. An indicator of a robust population structure of shad would show about 30% of the returning fish in any one year being a repeat returner. Unfortunately today many populations have far fewer repeat spawners, including in the Connecticut River watershed where less than 8% are returning adults.

So as we see the shadbush blooming every spring and we wait for the return of the shad, river herring, eels, and lampreys here at American Rivers, like our many partners and collaborators, we recommit to our work to remove dams, remove pollution, and work for climate justice.

We’re doing this work for the fishes. And we’re doing the work for you.

Want to read more?

A charming children’s book about shad migration is When the Shadbush Blooms, written by Carla J. S. Messinger a Turtle Clan Lenape member and Susan Katz.

North Carolina SeaGrant has a good summary of how climate change is impacting shad migration.

Going really deep, you can read a management plan for restoring shad populations in the Connecticut River watershed.