Guest blog for the Southwest River Protection Program by Mike DeHoff, Returning Rapids Project

Recently I found myself looking up the definitions for “cubic feet per second” and “acre feet.”

Cubic Feet Per Second (cfs) – a means to measure water in motion.

Acre Foot (af) – a means to measure impounded water.

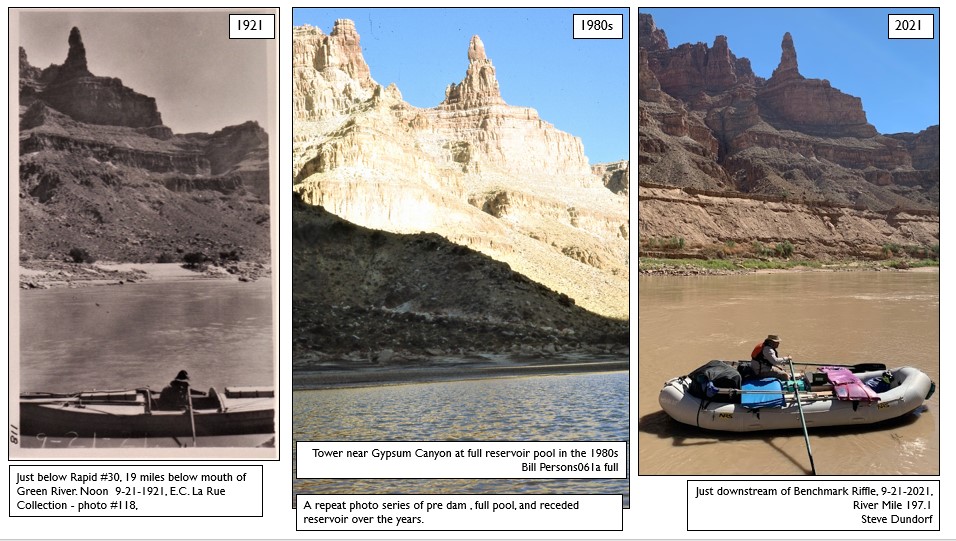

When Lake Powell reservoir behind Glen Canyon Dam was full or nearly full in the 1980s and 90s, both means of water measurement could be found in Cataract Canyon. In the heart of Canyonlands National Park, Cataract Canyon starts where the Green River and Colorado River come together in a craggy and uniquely sublime landscape where sun, sandstone, and ravens dominate the 2,000-foot-deep canyon system. This 41-mile stretch of river corridor is the furthest upstream section of the Colorado River that was affected by Glen Canyon Dam’s impoundment of river water.

Much like other western spaces, the boundary between river and reservoir was drawn with manifest destiny in mind. Elevation was used to create this boundary, drawing a topographic line from the massive concrete dam structure that sits 186 river miles downstream from the heart of Cataract Canyon. Three thousand seven hundred and twenty feet above sea level designates a man-made water storage basin for the reservoir known as Lake Powell.

Let's Stay In Touch!

We’re hard at work for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

Anyone who traveled through Cataract Canyon in the last two decades of the 20th century would have encountered both cubic feet per second and acre-feet: Cubic feet per second as a flowing living river for the first 40% of Cataract where boaters were greeted with a symphony of successive rapids. Then the river would slow down and the water’s character would change – not only in color as the river dropped its sediment but also in definition. In the heart of Cataract Canyon, you had to travel across miles of impounded water – many thousands of acre-feet of impounded water – until the canyon walls finally permitted a place where a road met the flooded river corridor and you could take your boat out of the water.

Over the last 20 years, this has changed. Cataract Canyon has seen a fascinating transformation as Lake Powell reservoir has receded in the face of climate change and overallocation. Now, even though the reservoir has left an impact, acre feet cannot be found in Cataract Canyon. Now it is all flow. With the full shift to cubic feet per second – to water in motion – ecologic characteristics that only a flowing river can bring have returned. Native plants and animals are thriving again in a now healthier high plateau desert canyon.

The reservoir, the dam, and its acre-feet of impounded water still persist downstream. Nature is challenging this engineered boundary allowing Cataract Canyon to be the last wild – non-engineered – section of the Colorado River. Downstream in Glen Canyon is where the Colorado does shift from its wild cubic foot per second self into being a commodity that is separated, distilled, stored, and used by millions of people for personal and economic benefit.

For anyone who finds rivers fascinating, Cataract Canyon is now one of the finest open-air river laboratories in North America. The Colorado River gathers a healthy sediment load as it flows from its mountainous source and into the expansive Colorado Plateau. When Lake Powell reservoir was full and the waters shifted from cubic feet per second to acre-feet in lower Cataract Canyon – all the sediment load carried by the river was dropped out of suspension and into the submerged river corridor. That sediment buried rapids, cultural and historic sites, side canyons, and a fascinating geologic record that was displayed in a deep canyon.

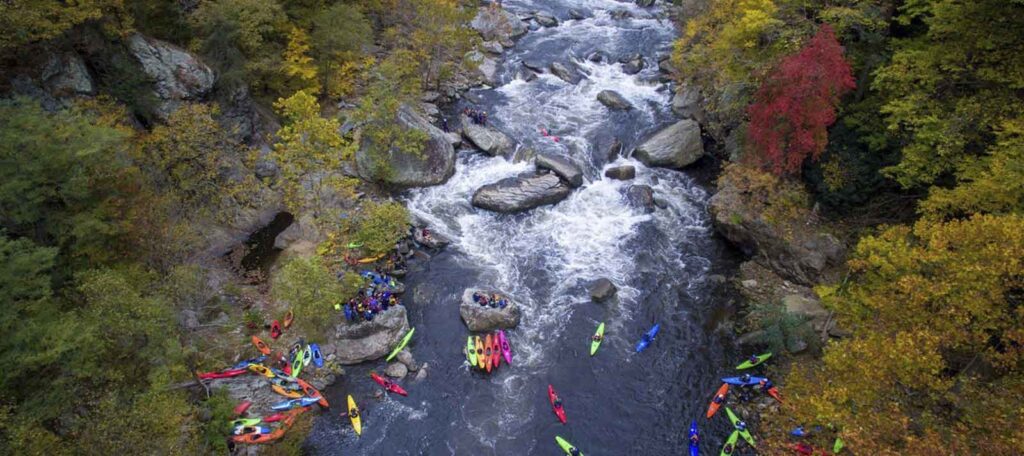

The natural processes that coincide with cubic feet per second are now at work remobilizing the sediment that was left behind as Lake Powell reservoir retreated from Cataract Canyon. Rapids that were covered with mud – the byproduct of impounding the Colorado into acre feet – are being carved back out. The river is reclaiming its gradient as Lake Powell shrinks to one-third of its former self. Where once there was the silence of still water, there is now the purring of eddy currents, burbles of boulders rerouting the current, and as of Fall 2023, 10 rapids have been carved back out of the mud.

When impounded water was contained in lower Cataract Canyon, the annual fluctuation of the reservoir level scrubbed the canyon walls of any vegetation. Thanks to flowing water, now there are willows, cottonwoods, and other native plants populating the river banks as they have out-competed invasives. Side canyons are scouring out the reservoir-deposited sediment and similar riparian recovery can be seen there as well. This speedy large-scale ecological repossession is incredible to observe and brings many questions to mind. Will the reservoir ever be so full that it inundates Cataract Canyon again? How do we manage this river corridor for the future? What resources do we prioritize over others?

This is just one capsule exemplifying bigger dilemmas we now face in the Southwest. While acre-feet of water may enable the quenching of economic thirsts in the region, it is a river flowing with cubic feet per second that will continue to bring life to the canyons and river corridors we revere. Mike DeHoff lives near the Colorado River in Moab, Utah, and is part of the Returning Rapids Project research team. Visit the Project’s webpage for a detailed dive into the returning rapids of Cataract Canyon, as well as photo matches, maps, data, preliminary findings, and a portal to donate.