Get back to “Good River”

5 million people rely on its water. 150 species of fish live within it. The Ohio River is worth protecting.

You could say the Ohio River is in Heather Sprouse’s blood. A sixth-generation West Virginian, Heather runs a small farm that relies on water from the Ohio watershed. She is also the Ohio River Coordinator for the West Virginia Rivers Coalition, an American Rivers partner organization dedicated to conserving and restoring West Virginia’s waterways and ensuring clean water for all. Sprouse connects with communities to advocate for clean water along the Ohio — one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2023.

“The Ohio River has always humbled me,” Sprouse says. “In parts, the river is a mile wide. From the confluence that begins the river in Pittsburgh to where it meets the Mississippi River in Cairo, Illinois, these waters are the lifeblood of our communities, our economies, and our ecosystems.”

The word Ohio comes from the Seneca (Iroquois) word ohi:yo, meaning “good river” or “beautiful river.” Collecting water from 14 states, from New York to Alabama, the Ohio River basin is one of the largest watersheds in the nation. It supports local economies and communities. The river also supplies drinking water to 5 million people and is home to 150 species of fish and wildlife. But that’s not the whole story.

The threats

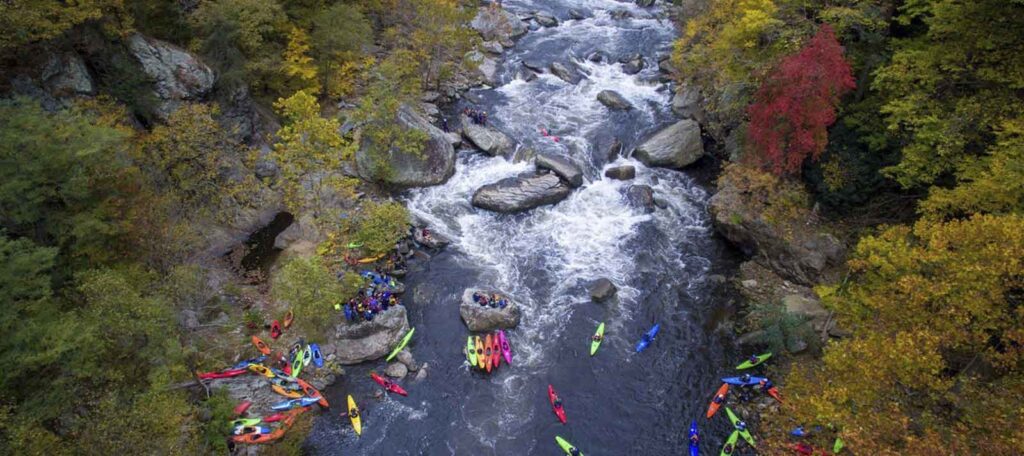

The Ohio is also a case study of many of the threats facing the 10 rivers named among America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2023: fossil fuel development, climate change impacts, such as extreme flooding, vulnerable wildlife, toxic pollution, drinking-water-safety concerns, access to river recreation, and lack of federal support. The list of threats is as varied as the six states the river passes through on its journey to reach the Mississippi.

Let's Stay In Touch!

We’re hard at work for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

A boom in hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia has resulted in toxic waste being barged down the river. That waste and other industrial pollution contain chemicals including PFAS — commonly referred to as “forever chemicals” — which don’t naturally break down and are linked to testicular cancer, kidney cancer, birth defects, and endocrine disruption. Meanwhile, coal-fired power plants have contaminated groundwater with arsenic and mercury. And nutrient runoff contributes to harmful algal blooms that make water unsafe for humans, pets, and aquatic life.

Recently, a Norfolk Southern train carrying toxic chemicals used to make plastic derailed in East Palestine, Ohio, 16 miles from the Ohio River. The train cars were filled with cancer-causing chemicals, some of which leaked into surrounding waterways and made their way to the Ohio River. More than 40,000 fish and aquatic wildlife died, and the communities reported foul-tasting and smelling water, rashes, and body aches. This chemical disaster is yet another reminder of the river’s vulnerability to toxic spills as industry transports chemicals through the watershed.

The Ohio River and its communities deserve better.

What must be done

“Unlike the Great Lakes, Puget Sound, and the Everglades, the Ohio is not designated as a federally protected water system,” Sprouse says. “Federal designation would open the door to much-needed funding for restoration, industry safeguards, and increased river monitoring.”

The West Virginia Rivers Coalition, Ohio Environmental Council, 3 Rivers Water Keepers, and other allies are working with the Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission and the Ohio River Basin Alliance to restore the Ohio River. They are advocating for a basin-wide restoration plan, much like the successful plan that exists for the Great Lakes. Based on insights gathered from communities across all 14 states in the Ohio River basin, the plan is five years in the making and will soon be submitted to Congress. It makes the case for recognizing the Ohio River as a protected water system worthy of substantial, sustained federal funding. It includes a blueprint for safeguarding drinking water, improving access to recreation, and funding pollution control efforts, water-quality monitoring, and ecosystem safeguards.

“We have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to invest in this river as a precious resource that connects us and offers us really high-quality lives,” Sprouse says.

American Rivers named the Ohio River among America’s Most Endangered Rivers® to proudly support local advocates’ call to action: Now is the time to set the Ohio on a positive trajectory that includes clean water, enjoyable recreation, and a healthier environment for all. We know that championing grassroots movements like the one gathering steam right now along the Ohio — and the nine other rivers on this year’s list — is the only way the river movement will protect 1 million miles of rivers that people live near and rely on. Because when many people, each in their own way and in their own place, pull together toward a common goal, we can achieve transformational change.

That’s exactly the kind of future Heather Sprouse envisions for her state and her river.

“I dream of people being able to safely eat fish from the Ohio River. I’d love to see fence-line communities leading the way in making decisions for their communities,” Sprouse says. “If we can shift to valuing and protecting the Ohio River as a resource for our communities, I believe we can create a livable planet, good paying jobs, opportunities for recreation, and a way to invest in our communities.”