Bringing Voices Together to Remove Obstacles: Three Dam Removal Handbooks Completed in Three Years

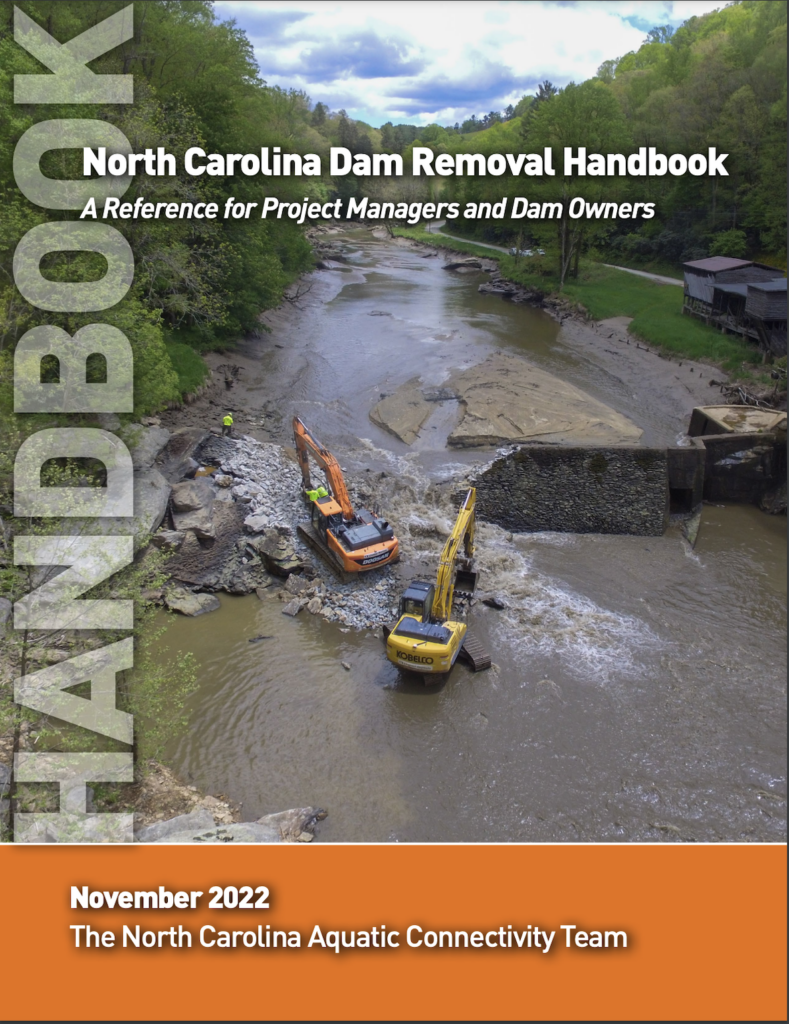

Announcing the Release of the “North Carolina Dam Removal Handbook: A Reference for Project Managers and Dam Owners.”

In 2015, Erin McCombs of American Rivers invited the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to join the North Carolina Aquatic Connectivity Team (ACT), a group focused on river connectivity and dam removal. This was an unusual move as regulators do not often get invited to participate in such groups — but the brilliant approach of the ACTs was to invite all voices to the table. My colleague and I hopped in a car and headed to North Carolina, unsure what – if anything – we could bring to the table. We were surprised when Erin urged us to consider how the regulatory/permitting process could be an obstacle to river restoration. I thought, “Clarifying the regulatory process in North Carolina was surely something we could do. How hard would that be?” As it turns out, it would take 7 years. But along the way, we would learn a lot and we now celebrate three dam removal handbooks completed in three years! But I’m jumping ahead.

I served my entire 35-year career as a regulator at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), working under federal statutes and regulations to protect, maintain and restore the environment. Serving under seven Presidents, the majority of my career was spent protecting rivers and streams under the Clean Water Act. The job was often contentious with countless hours spent across the table from folks with widely divergent, strongly held positions. Perhaps surprisingly, I came to value those widely diverging positions. Early in my career as a field inspector and enforcement officer, I learned that listening to all voices often resulted in win-win outcomes that were better for the environment and often had numerous, often unacknowledged economic or other co-benefits.

Let's Stay In Touch!

We’re hard at work for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

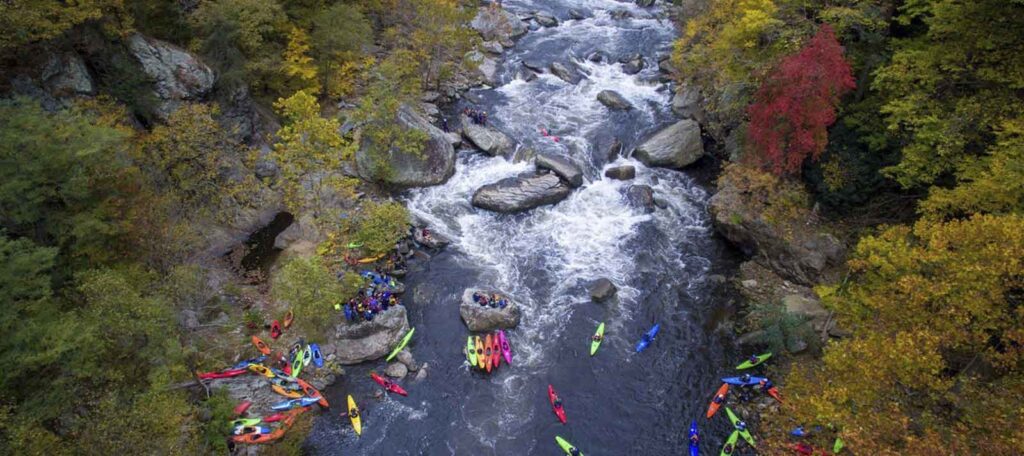

For the past 14 years, I served as technical lead for addressing pollution from hydrologic alteration, such as dams, diversions, and surface and groundwater withdrawals for the Southeast. This was sometimes an area of great controversy, but over the years, removing dams to restore the natural infrastructure of rivers and streams emerged as a concept on which almost everyone agreed. Dam removal restores connectivity for fish and other aquatic life, enables threatened and endangered species to thrive, re-establishes thermal and sediment regimes, and restores dissolved oxygen and could accelerate long-delayed land building in the coastal zone. Dam removal could enhance local economic development, restore safe river recreation, and remove public safety hazards. Where appropriate, the EPA supported these restoration projects, published dam removal success stories, and provided EPA grants.

In 2016, I was offered an opportunity to pull together a team to develop national guidance on how dam removal is viewed under the Clean Water Act. It was an opportunity to clarify the ecological and water quality benefits of removal, as well as co-benefits to public safety, economic development, connectivity, river recreation, and more. Keeping in mind Erin’s request, we sought to clarify the permitting process. One obstacle was instantly clear – the process was different in every state – and in each of the 38 Army Corps of Engineers Districts. We could not fully clarify the process in a national document.

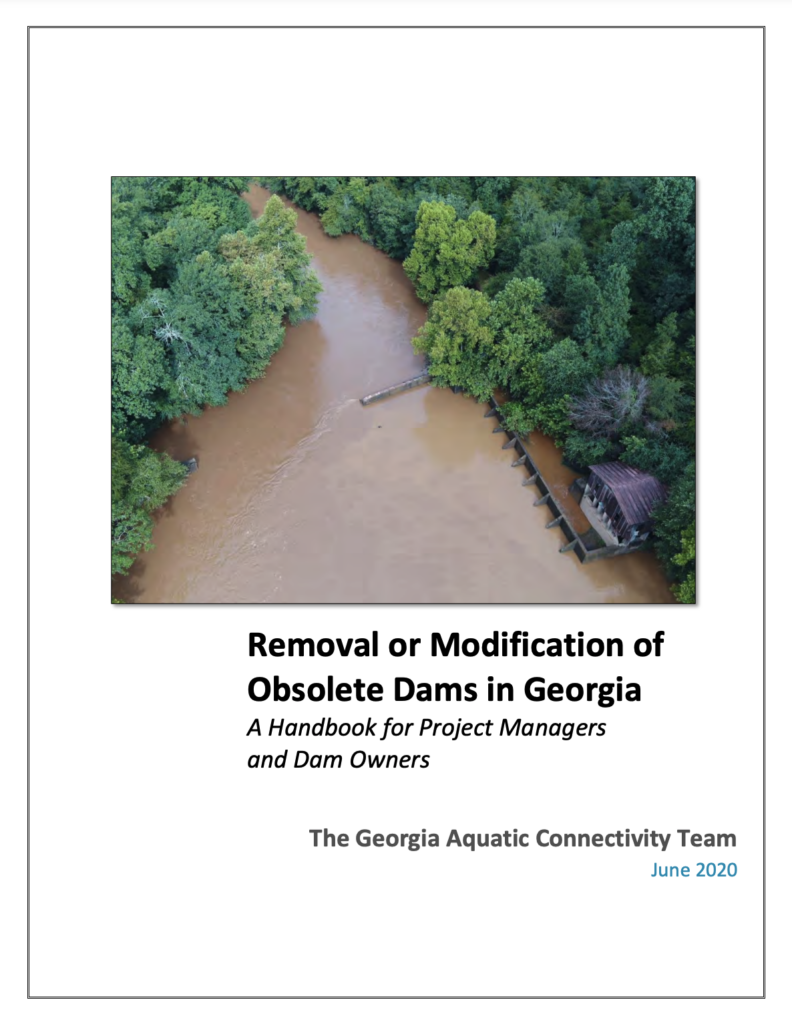

To clarify the process at the state level, we started with a group from the Georgia Aquatic Connectivity Team including state and federal regulators, natural resource agencies, the University of Georgia, utilities, dam owners, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), determined to capture the information needed for any project manager or dam owner interested in removal. It was not as straightforward as we hoped – there is no one agency that is fully over all dams or the process of dam removal. Through productive conversations, we drafted language collaboratively and outlined regulatory processes without promising regulatory outcomes. In June 2020, the Georgia Dam Removal Handbook was published – a state and US Army Corps of Engineers-specific guide for dam removal. The document has been downloaded hundreds of times. One email we received in response stated, “…check out the contributors on this document. Can you believe all of these people worked together?”

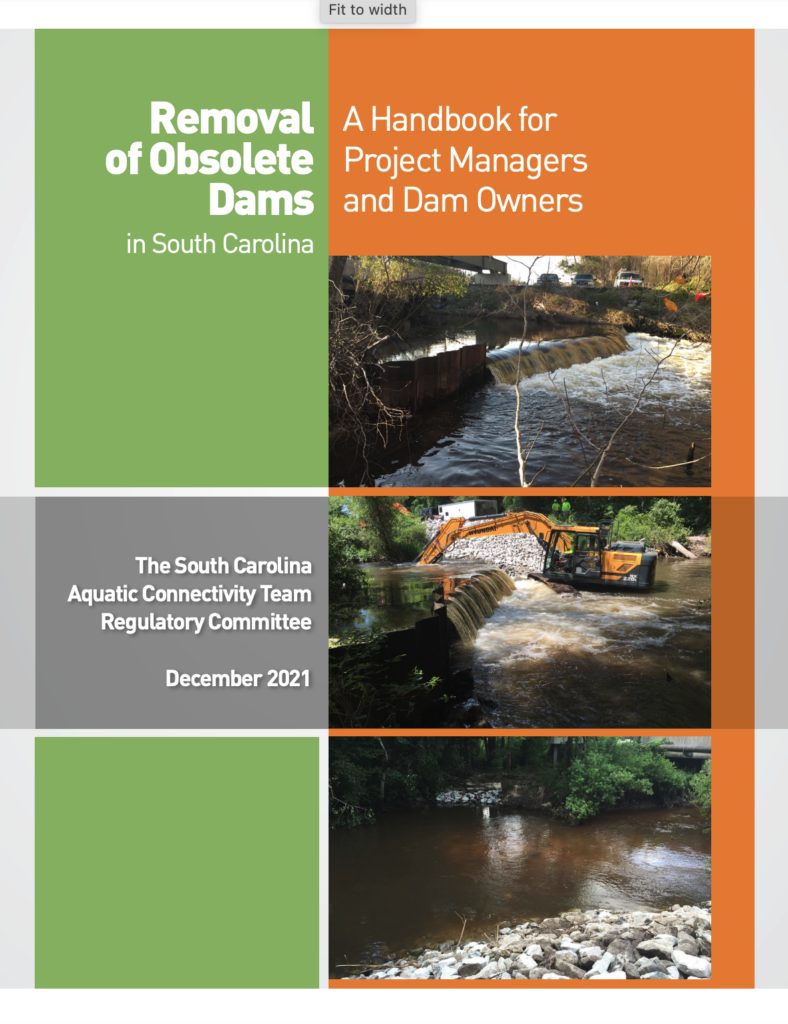

The following year, American Rivers asked us to pull together a Regulatory Committee for the South Carolina ACT to create a state- and Corps-specific Handbook. This time, we were prepared to hear all of the voices and urged them to tell their story of dam removal – which was different than Georgia’s. We spent six months learning each other’s processes and in December 2021, published the South Carolina Dam Removal Handbook.

I decided to retire in October of 2022. I had a lot to wrap up, but it troubled me that I had never fulfilled my promise to Erin to clarify the regulatory process for dam removal in North Carolina. Erin gave me a hard nudge. We pulled together an experienced group of state and federal regulators, state and federal natural resource agencies, and NGOs with extensive experience in dam removal who agreed to work together in record time to create a Handbook. North Carolina is one of the most successful southern states for dam removals and we wanted to tell North Carolina’s story from the mountains to the sea. For the first time, we included the tribal perspective on dam removal thanks to the input and perspective from the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Eleven days before retiring, we turned over the NC Dam Removal Handbook final draft to Erin. We completed three state- and Corps-specific dam removal handbooks for the Southeast ACTs in three years. I hope the publications, and the relationships formed along the way, will help to significantly remove regulatory barriers to the restoration of rivers and streams through dam removal in the Southeast. Thank you to all who contributed to this Handbook. And special thanks to American Rivers, The Nature Conservancy, and Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership (SARP), for creating collaborative platforms through the ACTS bringing disparate voices together to have meaningful collaborations – and for not being afraid to invite a regulator to the table.

This is a guest blog written by Lisa Perras Gordon, (retired) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

1 response to “Bringing Voices Together to Remove Obstacles: Three Dam Removal Handbooks Completed in Three Years”

If a dam has to go, it would be far better to convert it to a bridge instead of completely removing it. This would save a lot of time, money and resources and greatly reduce pollution and landfill.

It would work at many dams. Some of them already serve as bridges. A bridge provides the best possible view of the river, not possible any other way, while allowing the river to return to its natural course, which is the only purpose of such projects.

If most of the dam is still in place, it would be easy to use it to block the flow of the river temporarily to prevent flood damage downstream.

Converting a dam to a bridge provides many benefits and no causes no problems.