Whispers of Water Called Gila – A Returning and Exploration

Guest blog by Leeanna T. Torres, 2021 Southwest Emerging Artist Scholar; American Rivers and the FreeFlow Institute

I’d been to the Gila before, many times before, but not like this. Never like this.

Santiago’s head cocked sideways, his little body limp, held up only by car-seat straps across each shoulder. Instead of mule panniers, food, and horse-tack in the bed of the truck, there are Legos on the floorboard, crumbles of colorful Play-doh, an empty Big-League-Chew bubble gum packet. Water bottles instead of whiskey.

Santiago sleeps as the first sight of the mountain is revealed, at last and for the first time in years, alive as can be, seen through my truck’s front windshield. Haven’t been this close – physically – to the Gila in sixteen years. But here I am again, my boy in tow.

I turn up the radio, and a part of me stiffens as we begin to ascend into the Black Range.

Santiago remains asleep as the truck swerves its way through all the turns, dozens of mountainous switchbacks. Llano turns to juniper turns to piñon turns to ponderosa. This two-lane highway, so familiar, yet I haven’t driven it in nearly twenty years. A playlist on the radio—Lucinda Williams, John Fogerty and Steve Earle, but also Las Hermanas Huertas, Paquita La Del Barrio, and Cornelio Reyna—familiar voices and songs, and the truck sways, and Santiago remains asleep in the back.

We cross into National Forest land, past the towns of San Lorenzo and Mimbres. Into Apache land, what the Warm-Spring Apache’s call NDE BEHNA, true name for the place we now call Gila.

At last, Santiago and I are here, and I imagine the water he’ll soon touch. Agua santa.

In May 2020, New Mexico Senators introduced the M.H. Dutch Salmon Greater Gila Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which would protect nearly 450 miles of the Gila and San Francisco Rivers and their tributaries under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the premiere federal river protection legislation in the United States.

But what does this mean to a six-year-old boy more concerned with Legos and MineCraft than any of the ‘boring’ news I read and watch?

The Senator’s email came through five days before Santiago and I set foot in the Gila, for the first time, together, mother and son.

Let's Stay In Touch!

We’re hard at work for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

Never really understanding much about legislation, and even less about congressional committees, I did know the power of law, so I read the Senator’s email carefully.

“My legislation to protect one of the nation’s most iconic and treasured rivers just passed out of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee with a bipartisan vote!…”

What did this email mean to me, a native Nuevo Mexicana? And what did this email mean to my six-year-old sleeping in the back seat, already three hours into our drive, up the valley into the Black Range, driving due east and closer to the great Gila?

“…The Gila and San Francisco Rivers are the heart of southwest New Mexico and are home to some of the most outstanding places in the entire West to go rafting, fishing, or camping…” continued the Senator’s email.

I thought of the time I first saw the Senator in-person, his tall stature, his chiseled face. I thought of what it was to have such power, such influence. A Senator, taut with insight and influence to propose legislation to protect a place and its resources. And what did it mean to protect anyway? Who defines ‘protection’, and what expandable definition can this concept have? Again, I thought of my own boy in the back seat of my truck. It was my duty now, to protect him. But how? And in both the immediate and deeper sense, what does it mean to protect?

Words from the email lingered; I too had worked in the Gila, much like Senator Heinrich, in the early days of my career. In what I’d gained from articles and interviews, he’d worked with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) on Mexican Wolf Recovery.

He was still doing great things for the Gila—he’d proposed legislation. He was making a difference. All I was doing was bringing my little boy to the Gila’s water,no power or political stature to my name. The email continued:

The Greater Gila watershed, including the San Francisco River and other main tributaries, comprises the largest remaining network of naturally flowing river segments in the Southwestern United States.

I thought of the many ríos that had shaped me, influenced me in more ways than words could describe. The Rio Grande of central New Mexico, its café-colored water flooding my Papa’s alfalfa fields each summer con benedición. The Rio Lucero of Taos, searching for Rio Grande cutthroat alongside Pueblo War-Chief staff and the tribal biologist of a federal agency; a wild July thunderstorm moved in, and we were taught humility in the deepest sense. The San Juan spanning both New Mexico and Utah’s corners; again, work had allowed me to know and learn about the ecology of a place most people only see in photographs, or now in Instagram posts.

Yes, rios had shaped me into the woman who now drove a truck heading deep into the Gila, a boy in tow.

“New Mexicans treasure the Gila because it provides unique and memorable outdoor experiences for families, spectacular scenery and wildlife habitat, and the foundation of a rural economy. Protecting the river will support enhanced water quality, local economic development, increased recreation opportunities, and healthy populations of fish and wildlife.”

And yes, I was a mother now, bringing my boy to a place important to me. It was this simple. This uncomplicated.

“It is time for us to provide the Gila with our nation’s highest form of protection and stewardship,” ended the Senator’s email. I thought about this last free-flowing river in our Southwest home. And I thought about how each of us who cared about this place, this río, had our part to play.

I couldn’t propose legislation, but I could sign petitions, I could remain aware and eager and spread the word about the Gila’s protection within my own familia. I could bring my boy to witness the Gila. It was this simple. This uncomplicated.

What Santiago didn’t realize is I forgot to pack a flashlight.

What the hell. How foolish was this? In all my hurried packing of food, sleep gear, water, emergency tools—in all my well-timed logistics, how the hell had I forgotten a flashlight?! I thought of the wild dark nights we’d be spending in the Gila, how this remote mountain-river-wilderness in southwestern New Mexico knew darkness. I’d forgotten to pack a flashlight.

And it was too late to turn back now. Already long past Hillsboro, past Iron Creek, Upper Gallinas, then Lower Gallinas. A winding Forest Service road. Already in the Mimbres Valley, I calculated the risk of this item I’d forgotten. My phone had a flashlight, and I had battery packs and a charger in my truck.

Santiago still asleep in the back. He didn’t care I’d forgotten a flashlight. At his age, carefree. I watched as the rio, adjacent to the road,ran wild—full, thick with a deep reddish-brown-color, clear remnants of an upper water-shed monsoon storm—evidence of rain. With evidence of rain in the river, I decided then and there we’d drive on. It was too late to turn back now.

The Gila River, a 649-mile-long tributary of the Colorado River flowing through New Mexico and Arizona, is also one of the longest rivers in the west. And I sit and wonder HOW to introduce my boy to this place.

The river is the heart, the lifeblood of the Gila Wilderness, National Forest, and surrounding landscape and ecosystem.

The Wild & Scenic legislation would protect 450 miles of river, keeping it free flowing in the face of development or other ‘use.’

But the question remains, HOW to introduce my boy to this place?

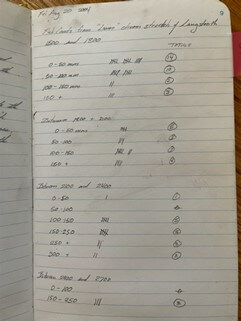

My OLD field notes as a fish biologist in the Gila read like this entry from 2005: Something tells you to listen. Something tells you to listen carefully. Thunder in the canyon. Rain speaking. Water speaking. And a cold August dampness in the air forming words on your skin like an orange tattoo.

It is now the year 2022—17 years later. I am no longer a fish biologist working in the Gila. I am a visitor again, as I always was. A visitor.

The yellow Rite-in-the-Rain hardcover book containing all my old Gila notes is only half-full of the notes I used to take while working deep within the Gila Wilderness, what now feels so long ago. The first date reads Friday, August 20th, 2004, and the last, March 28th, 2008. Four years spanned my formal working days in the Gila Wilderness and River, a wannabe biologist among the headwaters, los rítos. I was a young woman, struggling to find my way into a career, but more honestly, through life, searching for a space of identity and understanding among men and wilderness.

I was introduced to the Gila long before I became a mother to a son. Even as a native Nuevo Mexicana, a brown girl raised in the farm fields of the middle Rio Grande valley, I did not know the Gila in my childhood days. It was a place I’d only heard of.

With today’s current climate conditions—megadrought looming in the American West—I search back through memory and time, trying to define for myself, as much as for my young son, why exactly the Gila has become so important to me.

The yellow Rite-in-the-Rain hardcover book containing all my old Gila notes is only half full. And as I drove INTO the Gila again for the first time in 17 years, I thought about all I’d written back then. More importantly, I thought of the empty pages the book still contained, what more I had to discover, what more left to learn.

JOURNAL ENTRY, 2005. In the mountains, thunder directs your thoughts. And bees gather around objects—your backpack, the bucket, the yellow book, wet shoes. Everything is the way the mountain wants it. In the rain, you’ve got to keep your head down, it teaches you humility. Sometimes the Gila is about slow and deliberate motion, or that thick smell of whiskey in a tin cup. Sometimes it’s about the way paper warps in the rain… There is yellow in only the smallest places of the mountain. In the flowers, on the bees, on the flowers. Most of this mountain is a thousand shade of browns and greens, and the combination of all this color is like waiting for the sound of water to break into you.

Your hands smell like tree sap and purple flowers. The rain has stopped, for now, and you wait for Richard to arrive from the upstream duty post. You listen for the sounds of his arrival – the splashing of water and gravel and rocks, the occasional breaking of branches, his movement downstream. There is stillness again, under a grey sky of occasional thunder, and we work through it all, a color green.

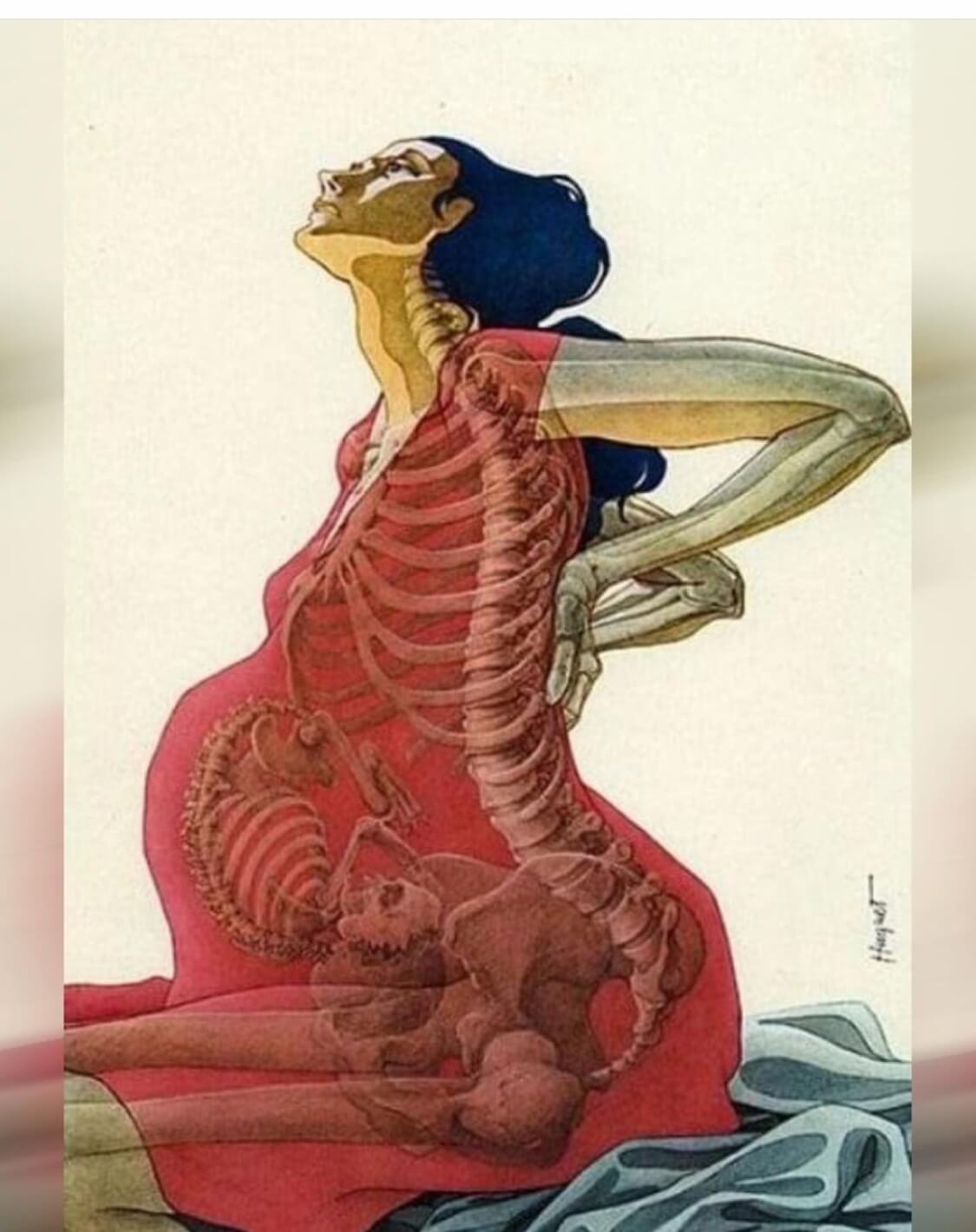

In her essay, “The Vessel & the Water,” Kailea Frederick describes, “In those nine full months, my womb was neither fully mine nor his, our bodies blurred so completely that even when he finally came through and out of me, our delineation of self remained soft and unfocused, a horizon line of hazy blue touching the forever expanse of the sky, indistinct in color or shape. I was the vessel that held the waters in which he grew” (https://humansandnature.org/the-vessel-and-the-water/).

My boy was born on a Friday, 2:51 am. I labored for 17 hours until at last the nurses gave the C-section order, and they cut him out of me.

“I was the vessel that held the waters in which he grew,” states Kailea Frederick in her gorgeous description.

Looking through my notebooks—the kind I’ve kept for years—of daily notes and ritos of time and place, I try and find the earliest instances, phrases, documentation of what it was like for baby and me starting off together as one. There are writings, mentions during pregnancy, but not after. Nothing in the days, hours, months, after his actual birth. They cut him out of me. This time frame, these days AFTER the baby’s birth—all my writing entries fall short.

I wrote nothing about the baby. I wrote about other things, many other things, but NOT about the baby.

This biologist and writer who was TRAINED and DISCIPLINED in writing and note-taking, could suddenly not write. I did not write about the baby, or even about me as mother.

Was I afraid to write the truth? Or at the time, did I simply not know the truth?

The closest I find to mention of baby or motherhood, or ANYTHING tangible, isn’t until one year and one month later.

Something in me was hesitant, afraid to write, until, at last, it wasn’t.

JOURNAL ENTRY, OCT 25th, 2016 (one year AFTER my baby’s birth). Eating fruit with a fork reminds me it is Tuesday, and last night Santiago woke at 01:30 AM, crying, but was calm and quiet as soon as I picked him up. He is comforted just by my touch. I hold him close to me, and the room is completely dark. He is leaning into me. I am holding him close and tight to my chest. I am just beginning to understand what it is to be a mother. At last, it feels like love to hold him.

My boy was born on a Friday, 2:51 am.

“I was the vessel that held the waters in which he grew.…” And yet it was a struggle, all the early days, a deep struggle, a wilderness even now I cannot name, cannot admit to. Where does one hide from the sin of a mother who cannot, does not, love in those early days? Even the expanse of the great Gila wilderness cannot contain such darkness. Even the free-flowing Gila River cannot wash away such disdain.

JOURNAL ENTRY, SEPTEMBER 2005. Soaking rain during the ride that took us six and a half hrs. Slept warm with the saddle blankets beneath a grey tarp in the tent that was set up between Jerry and Johnny. As for now, I am alone with this mountain, ‘watching’ the two lowest buckets on Langstroth creek wondering if I will make it out of here unharmed. In many ways you are useless among all of this. Out here, if you get hurt, you’re on your own.

The sun keeps coming in and out, in and out…there is thunder. Orange flagging marks the lowest bucket of chemical treatment as we work. Thunder. And it is only fourteen minutes past noon. Yesterday at this time we were in the saddle, taking the trail that eventually leads into and out of Hell’s Hole.

The presence of thunder is never mistaken for anything other than thunder. And yet here in the mountain it is common. They say these are the days of the monsoon. It is so different to experience all this wetness and rain than to merely hear news of it through a coworker. So much more terrifying to experience. It forces you into being right now, right now, right now. And never any time before or after or otherwise. The way thunder-rain comes into a canyon is fast.

Thunder-rain thru the mountains. Dressed in a color we had never seen before. Speaking something blue. And it rumbles the silence right out of the trees while the wildflowers are busy at conversation.

When working in the Gila, it was always about the fish. But also, it was never about the fish. Gila trout, a federally listed species, was reclassified from endangered, down to threatened in 2006.

Gila trout: one of the rarest trout species in the United States.

Native to mountain streams of the Gila, their populations HAVE seen an increase in total WILD populations through recovery efforts over the years.

In 1992, their numbers were estimated to be less than 10,000 fish older than 1 year.

In 2001, the population in New Mexico was estimated to be over 37,000.

Intensive stream renovation and transplantation efforts have worked.

But what does it mean to ‘recover’ a species? What does it mean to protect a place? What does place TEACH us? How do species and ecologies of PLACE inform our own human lives, and why does any of it matter?

I used to work on fish-recovery efforts: treating upper watershed creeks with chemicals, eliminating all fish existing within very specific stretches to ‘make room’ for this rare and threatened trout. I used to pack in to the Gila Wilderness with large crews, mostly men, working for days that turned into weeks.

Now I am mother to a young boy. I no longer work as a biologist or field tech.

But even now, I still ask, often and always, what does it mean to ‘recover’ a species? What does it mean to protect a place, how do places become IMPORTANT to us?

I reach out to Chad Baulmer, the USFWS biologist currently assigned to Gila trout public inquiries. I reach out via email, and he replies, tables and numbers attached. But what I really want to ask him is, “Did your heart skip a beat when you first held a Gila Trout? Do you still remember the fire-orange along its lateral line and fins? What excitement still lives within you since the first time you witnessed this species in the wild, this endemic fish, this species worth saving?

But I don’t write that in the email. Instead, another ríto wells up inside me, another question, another source. It begins slowly, agua moving thru soil and boulders of a high-mountain forest. Headwaters of my alma—the smallest ríto already inching its way into the expansive eternity of an ocean source not yet realized. “Thank you for the information,” states my emailed reply to Chad the biologist, and I sign the end of the email with my three initials—LTT—the way the field fish biologists taught me so long ago, always 3 initials instead of just two. Three initials in honor of my old field days of taking notes in the Gila. Will Chad the biologist notice this end-of-email signatory? Will he sense I TOO once worked on recovery efforts? No, he doesn’t know me. And I smile at my own anonymity.

For a good six months or more, Santiago’s favorite snack has remained apple slices and Funyuns. Although his likes and dislikes change much like his padrino, my brother, THIS snack of choice has remained. Yes, apples and Funyuns. Yes, those ridiculous salty corn rings sold in a bright yellow bag, marketed to look like onion rings, but really the only ‘onion’ ingredient is ‘onion powder’ listed as one of the very last ingredients. My boy loves apple slices and Funyuns, and I won’t try to describe to you the wicked-strange breath out of his little laugh after he eats his snack.

“Mama, I LUHHHOVE YOU,” he pushes out hot intentional breath trying to reach me as he jokes, knowing this annoys me as much as it makes me laugh.

“Uhhhgg, go brush your teeth!” I yell back as he continues to breathe on me, laughing, trying to climb up on me, pulling on my hips while I push him back, my palm on his forehead. Both of us laughing, Funyun-crumb residue on his shirt chest and belly, his fingers sticky from the apples too.

“No, for reals, go brush your teeth,” I finally insist, and off he goes to the bathroom, stepping up on a little stool to reach the sink. My boy brushes his teeth, and I stand outside against the door, a space where he can’t see me, and just listen to him hum a little song while he brushes his teeth. Looking down at my own shirt, there’s Funyun powder residue all over me now, but I leave it there, and keep listening until he’s done, and in a hurried rush he slams the wood cabinet drawer shut with a loud thud as he puts his wet toothbrush away.

River and boy, river and boy—both teach me not only about wildness, but about what it is, not to be a mother, but to become a mother.

Just as rivers become rivers from headwaters, so have I struggled to become a mother. Gentle. Peaceful. Teacher. Loving.

Water connects us in obvious ways. But it’s the smaller ways, the intimate ways that take us by surprise, that hold a different color, that remain.

Thus, in many ways, mine is a story about water—agua. Es una estoria de cambio—change—and of how our relationship to a place—an element, like water, like mountain, like wilderness—can change over time.

I lean into the fragments, the many tributaries of my querencia.

Querencia: a deep love of place, or belonging to a place. Fragmented tributaries of experience, stories, and time spent IN and AT the Gila’s water. Creeks, streams, and headwaters converging and leading always into the deeper understanding.

The word querencia is a popular term in the Spanish-speaking world that is used to express a deeply rooted love of place or people. And though it’s a Spanish word, the idea of Querencia is truly universal, its translation endless and ever widening.

Querencia: the place of your deepest identity, your deepest longing; a place in which we know exactly who we are; the place from which we speak our deepest beliefs.

Writers such as J. Drew Lanham might refer to this concept as “home-place.” Similarly, Robin Wall Kimmerer might call it “kinship.” But here in Nuevo Mexico, some of us call it “querencia,” that which anchors us to the land. A deeply rooted knowledge of place.

It is strange returning this way, returning to the Gila not as a fish biologist, but as a mother. My title, my qualifications are gone. I still have the university degree and an old resumé, but what does that matter when returning to a place you knew and observed from a worker’s perspective?

I think of the men who taught me about and in this place. Jim, Johnny, Dave, Vern. Where are they now? I think of the horses and mules, those who had nicknames, and those who didn’t. Where are they now? Time has passed. Seasons and years.

“Mama, can you take off this Lego for me?” asks Santiago, holding up a little tower he’s constructed. “This yellow one is stuck to the black one, and I want to change it but can’t get it off.” He holds up his toy creation as I try to get our gear out of the truck and set up for our stay in the Gila.

His little toy tower, and I am focused on logistics. I am too caught up in the past to notice the urgency right in front of me. The present. The now.

That night my boy and I sleep under a Gila sky, the cosmos laid out in deep black, a scattering of constellations. “What’s that one?” asks Santiago. “And what about that one?” playfully. “No se, mi hito, I only know the Seven Sisters.” There is so much I don’t know, and yet he’s aways asking me for the answers.

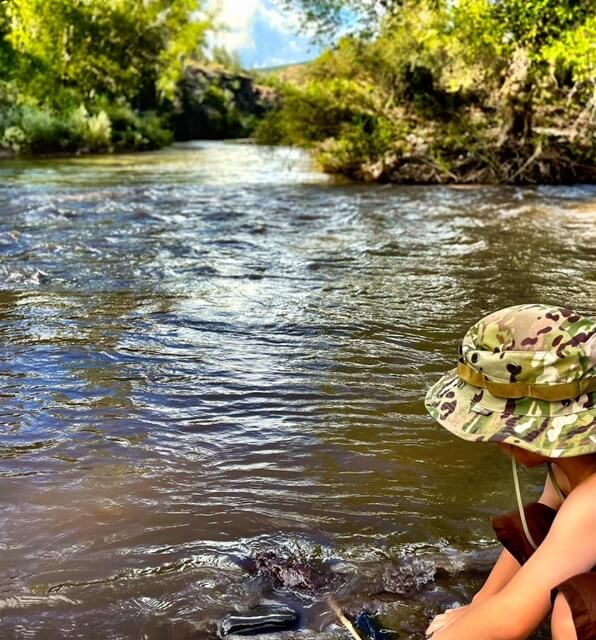

The next day, we find a ríto named Sapello. We look for fish, turn over rocks, eat apples and a bag of Cheetos at the edge of where the stream runs endlessly. I sit there, considering the Gila as STILL the last free-flowing river in NM, thanks to the EFFORTS of so many intent on protecting its wild and native flow.

Willow and olive trees provide shade as Santiago plays—splashing his feet in the water, throwing sticks, asking, “Is that a fish, Mama, is that a fish?”

“No loco, that’s just algae, see?” And we proceed to pull some of the silky green off rocks, exposing it above water to get a better look.

We had no real agenda that afternoon, I realized later, and Santiago never asked for one. We were just at the creek. Looking for fish? Climbing rocks? In its very essence, we were just at the creek.

What sort of privilege is this? To have time and resources to just play in the water. Previously, all my time in the Gila was dedicated to work. Labor. Pack this, plan that, pack in on mules, take notes on water quality, habitat elements like substrate and bank-width, then pack it all out. This is how it used to be. This is who I was. Trabajo. Work.

What Santiago was suddenly offering me was the notion of playfulness, enjoyment. I’d never had that in this place. Even as a child, we were not a ‘family’ of ‘recreators.’ Papa worked. Mama worked. We didn’t take camping trips, or boat at the lake, or fish in the streams. Papa worked. Mama worked. Then I worked. Then when I was introduced to the Gila, it was with men and work and whiskey. But here I was with my boy, and his playfulness surprised me.

We’re still exploring, Santiago still playing, and I begin to sense and see a monsoon storm moving in.

“Hey, let’s go,” I say to Santiago. Downstream, thunder rumbles, the sound getting closer than just a few minutes ago. I hustle, making sure we’ve got everything, preparing to leave.

I start scrambling, moving faster to get our things gathered up, backpacks, rain jackets, water bottles, snacks. Santiago is still playing. “Hey, for reals, let’s go,” I say to him, my tone dropping. “Ok, ok,” he responds. He’s still at the edge of the water. “Let’s go, let’s go,” urges my voice out loud again. Still, I’m scrambling, watching the sky, the movement of storm, but also making sure I’ve picked up everything.

It’s then I hear: from the water’s edge, Santiago says to me, “Mama, bless…” I turn to see him standing in the water, at its edge, calling me over.

I go to him and almost instinctively, I crouch down. We are both at the water. Mother and son. Presence of incoming rain tells me we should hurry. But Santiago’s sudden calmness tells me not to rush. “I gotta bless you, Mama,” and he puts his hand in the stream, and with a scooped hand, he pours water on my head.

Then he does it again, this time smushing his hand in my hair. More water, messing up my hair with his motions. He scoops water from the creek. Again. Again. He’s getting my head all wet.

A blessing.

I think then of all the times I’VE blessed my boy, a tradition given to me by my own mother and father. When we were children, Mama and Papa would always bless my brother and me with a holy sign, a physical gesture. With the right hand, they’d touch our forehead, chest, shoulders, speaking aloud, “padre, hijo, spiritu santo…”

A blessing.

They’d bless us when we’d leave the house. They’d bless us if we’d go with our primos or to Nana’s house. They’d bless us before going to school. They blessed me when I left to the Marine Corps. This blessing also extended to include water—especially on June 24th, dia de San Juan—when Papa would playfully bless us with water, spraying us kids with the hose, or splashing water on our faces first thing in the morning.

Mama and Papa were always blessing me. Even today, they still do. And in turn, I’ve extended this tradition to my own boy.

For the last six years, I’d blessed Santiago too. But in my own way, I’d also extended this tradition, often blessing him with water. When walking along the Rio Grande near the house, I’d say, “Bird, come here. Let me bless you.” I’d touch my fingers to water, then to his forehead.

When playing or working near the acequias at home, I’d dip a finger in the water and bless him, finger to water, then to his forehead.

His first time at the San Juan near Pagosa Springs, I led him to the stream edge, scooped water from a riffle, and wet his head. A blessing.

This is what my familia did. It is what I’d been taught. It was the action I took.

But what I didn’t realize is that it had translated. THIS small action had translated. Santiago had been paying attention, and now suddenly, completely unprompted, he was asking to bless me. He was asking to bless me with Gila water, and all I was concerned about was outrunning the rain and ensuring we’d picked up all our Cheetos bags.

Santiago scooped up more water from the creek. He poured water on my head, messed up my hair. A blessing from the ríto. My boy, suddenly blessing me.

As a New Mexico native, born a daughter to this American Southwest, my desert life has always been a story about water—agua.

I’d followed through television and reported news stories, the battles and controversies to dam the Gila River. I’d supported federal legislation proposals to protect certain portions of the river. I’d tracked the news stories as fires and then floods moved across the Gila landscape.

But among and within all of it—current, historical, political, or otherwise—it is our RELATIONSHIP to place that inspires action, cambio, querencia.

My head now dripping with water, I look up. Santiago is smiling. He’s smiling and almost laughing. It isn’t him being travieso (ornery or badly behaved), it’s him being playful. And I let him.

“One more time,” I ask him, and immediately he reaches for more water, drips it on my head.

His playfulness isthe prayer offered to the Gila. His playfulness is a re-envisioning of my own relationship to this place, mi querencia. I am not here in the Gila as a girl who works, but as a woman and mother now.

Similarly, my deep hope for Santiago is that this playfulness will also be the origin of this as his own querencia. Maybe. Si Dios quiere.

Thunder rumbles in the distance, not low and deep as before. “Eeee, let’s go,” I say to Santiago. “Ok!” he replies and jumps easily and willfully up and out of the stream, his botas sopping wet. He could care less and starts running up the trail. I scoop up bags, wipe water from my face, all of it still from Santiago’s playful blessing.

Then rain begins to fall. We rush back up the trail, upstream toward the truck, Legos still scattered on the floorboard, apple juice instead of whiskey.

THE END.

Leeanna T. Torres is a native daughter of the American Southwest, a Nuevomexicana who has worked as an environmental professional throughout the West since 2001. Her essays have appeared in various print & online publications (Blue Mesa Review, High Country news, High Desert Journal), as well as anthologies. She is also currently at work on a creative-non-fiction book manuscript centered-on landscape, culture & querencia. Leeanna received the 2021 Southwest Emerging Artist Scholarship from American Rivers to participate in a FreeFlow Institute writing workshop with William DeBuys on the Green River, which led to this essay.

Thank you to Senator Martin Heinrich, Senator Ben Ray Lujan, Representative Melanie Stansbury, and Representative Teresa Leger-Fernandez for working with their leadership to try to get the M.H. Dutch Salmon Greater Gila Wild and Scenic Rivers Act passed before the end of 2022!

2 responses to “Whispers of Water Called Gila – A Returning and Exploration”

Beautiful story. I grew up in the desert of Las Vegas NV. But, my family spent MANY memorable times on Lake Mead, created by Hoover Dam on the Colorado river. We fished from a boat, skied, and swam the water and had lots of picnics on the shore of the lake. My parents had the same house in Las Vegas from 1943 until sold 61 years later in 2004. I understand that Lake Mead is being irreversibly drained by the unsustainable population and their thirst for golf courses, grass lawns, swimming pools…

It´s all another aspect of global ecocide that is leading us into Mutually Assured Death; without any nuclear weapons ever being launched by adversaries… My 21yo granddaughter has decided against having children because she sees no future for them. I´ll be 80yo in January 2023 and seriously wonder if I can die a natural death before Mother Earth gasps her last breath and collapses…

p.s. My mother´s name was Lee Anna in high school in Denver CO.

She changed to Leanna when she and my dad moved to Las Vegas.

p.p.s. I´m an expat living in Valencia Spain. I am too disgusted with the usa system of exploitation…

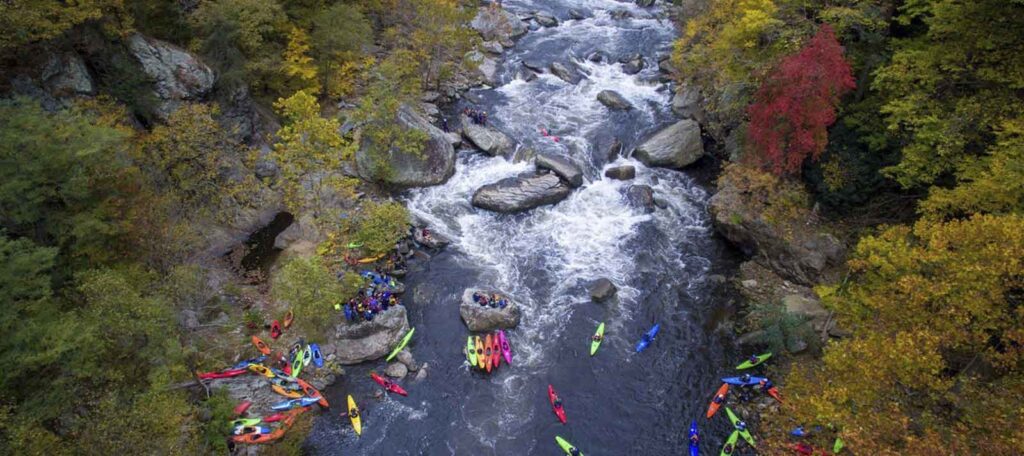

I was privileged to hear Leeanna speak at the 2022 Gila River Festival. What a gift and inspiration to those of us who have experienced the Gila and love her dearly. I rafterd the Gila in March 2020 just before Covid lockdown. It was a magical time.