Why Protecting Wild and Scenic Rivers is Vital for Wildlife Resilience

Water is arguably our most precious resource—especially during times of drought and fire.

Kyle Allred is a physician assistant who has practiced in both family medicine and urgent care. He also has a keen interest in wilderness and travel medicine and is an instructor at the National Conferences on Wilderness Medicine. Kyle lives in Ashland, Oregon.

Kyle Allred says he’ll never forget standing in 40 mph wind gusts as his neighbor told him a fire was heading toward them, and they needed to evacuate—now.

“It was frightening to see a massive, swirling, dark cloud of smoke heading toward us as I gathered a few things along with my car keys,” he says. “The magnitude of the fire didn’t sink in until I evacuated to a vantage point where I could see the town of Talent and house after house go up in flames. Intermittent explosions, presumably from propane tanks, sent shivers down my spine.”

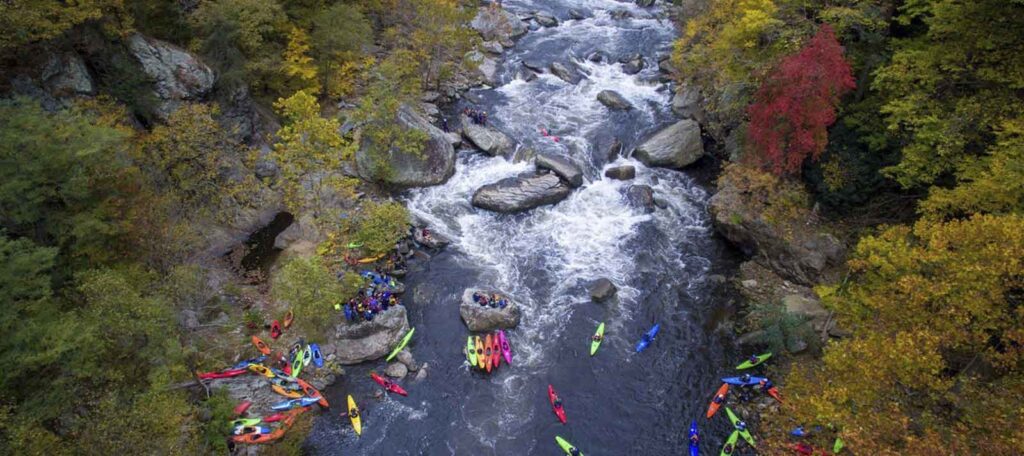

Allred grew up in the small towns of Talent and Ashland in southwest Oregon, in the Rogue River Drainage that he was watching go up in flames that day. In fact, his parents took him down the Wild and Scenic section of the Rogue River for his first river trip when he was just six months old.

“I believe the river landscape had one of the biggest influences on my upbringing,” he says. He started raft guiding on the Lower Klamath River when he was 14 years old and spent nearly every summer in the Klamath drainage for over 20 years. “I developed a deep appreciation for the nature that lives in and around rivers,” he says.

Over the course of those years, like many others around the world, Allred began experiencing a significant increase in nearby wildfires and smoke there in the valley. But the most traumatic experience so far, he says, started on September 8, 2020, with what’s now known as the Alameda Fire.

After quickly evacuating his home, he watched from afar as flames consumed the town of Talent. Scattered communication with family and friends added to the sense of chaos. He describes bumper-to-bumper traffic and the relief that came with finding that everyone he knew in the fire’s projected path was OK.

“But the fire raged on and it was a helpless and humbling feeling to hunker down and watch,” he says. Allred was certain his house would be destroyed. About 24 hours later, he learned that the fire had burned within 100 yards of it—but his neighborhood had been spared.

Almost half of the structures in Talent and the next town north—Phoenix—were not so lucky. Amidst a pandemic, thousands of people lost nearly all of their possessions, were displaced, and needed a roof over their heads, he says. “The firefighters and first responders were nothing short of heroic in their response to the fires with limited resources.”

Less than a year later, Allred says the rebuilding effort continues, and the burned corridor along Bear Creek is regrowing a new post-fire character. But most people are nervous about upcoming fire seasons amidst historic drought conditions.

Let's Stay In Touch!

We’re hard at work for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

“As the climate and wildfire crisis worsens, the protection of rivers seems more important than ever,” Allred says. “Water is arguably our most precious resource—especially during times of drought and fire.”

In many of the communities Allred has lived and worked in, the health of the community is linked to the health of the rivers within them. “For example, ample fish populations allow Native communities, the fishing industries, and tourism industries to all sustain their respective livelihoods,” he says.

Senator Wyden, as part of his River Democracy Act, is including measures for fire management and funding. Drawing from his experience with the Alameda Fire, Allred is hoping to see that include incentives for home and business owners to use or upgrade to fire-resistant materials and incentives and grants for property owners to manage the vegetation on their land in a way that helps prevent fire growth/spread. And with his background as a medical professional, he’s hoping for more resources and education about air quality, safe outdoor activities amidst smoke, and smoke mitigation through air filters, purifiers, mask or respirator use.

Watching his community rebuild after the fire, Allred sees the need for a simple, integrated, perhaps statewide, fire and smoke warning system or app for communities. It could be the key to evacuating people safely—but it could also help connect people to opportunities to help in the aftermath of a fire.

“I’ve witnessed the impressive resilience of the people of Southern Oregon who’ve been affected by fire,” he says. “It takes incredible resilience to lose your home, be displaced, and navigate the many challenges to follow from finding a new place to live, to dealing with insurance companies, to finding a new job.”

Allred takes inspiration from his local rivers, which he says are incredible examples of resilience. “We’ve seen dam removal and other mitigation measures result in an amazing renewal of river health and riparian species. If given the opportunity to thrive, rivers will. And as a result, the surrounding communities will have a better shot at thriving as well.”

He hopes his community will lean into that sense of renewal, too, instead of anger, fear and sadness. “In the aftermath of the fire, I hope that the wonderful and resilient sentiment of ‘We will rebuild’ will be expanded to something like, ‘We will rebuild: effectively, creatively, and in a way that minimizes fire risk and spread.’”

Learn how Oregon Senator Wyden’s River Democracy Act is fighting catastrophic wildfires and climate change here.