Neuse River: 2022 River of the Year

On the 50th Anniversary of the Clean Water Act, a North Carolina river is on the comeback

American Rivers is excited to announce the Neuse River as our 2022 River of the Year. The Neuse has seen major progress in recent decades, with cleanup efforts improving water quality and restoration efforts improving habitat for wildlife and access for fishing and boating. The river’s rebounding health has benefited wildlife and people alike, and as the nation celebrates the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act this year, the Neuse illustrates how positive steps for clean water benefit both the environment and economy.

Returning a river to good health does not happen overnight, nor is it a guarantee moving forward. For us to continue celebrating the Neuse as a regional and national treasure, we have to remain diligent and pay attention to threats to the river. The growing effects of climate change are continually putting new stresses on the river and its water supplies, and we must ensure that the benefits of a healthier river are enjoyed equitably among the communities in the watershed, especially communities of color that have faced systemic environmental injustice and continue to bear the brunt of river pollution and increased flooding.

Tom Kiernan, President of American RiversThe River of the Year honor celebrates the outstanding progress toward a cleaner, healthier Neuse River that is the lifeblood of this region. This river is a national success story, and we need to keep writing this story together.

We support frontline partners who are working hard to ensure a just, equitable, climate-resilient future for the millions who live along the Neuse. Everyone who lives in the watershed should take pride in the river and its progress.

Communities along the Neuse River are setting a national example for river stewardship. We must use these lessons to ensure healthy rivers, equitable access and clean water nationwide.”

About

The iconic Neuse River’s name is derived from the Neusiok people, who once lived near the mouth of the river, and means “peace river,” likely because of its slow moving nature in contrast to the powerful Cape Fear to the south. The Neuse watershed is also the traditional territory of numerous other tribes including the Lumbee, the Skaruhreh/Tuscarora, the Saponi, the Occaneechi, and the Cheraw.

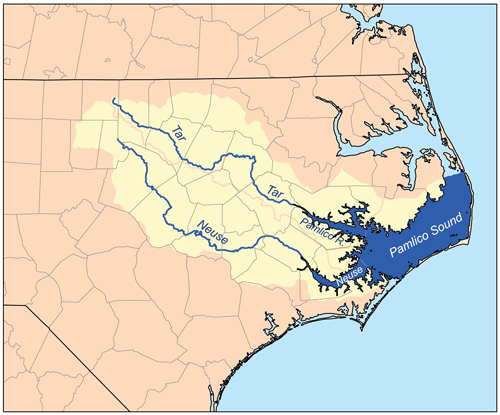

Flowing 275 miles from the Piedmont of North Carolina to Pamlico Sound on the Atlantic coast, the headwaters are located at the confluence of the Eno and Little Rivers, just before flowing through Falls Lake Reservoir outside of Durham, NC.

The main stem pours out of the 12,000-acre Falls Lake Reservoir — a well-loved recreation destination and the drinking water source for half a million people — at Raleigh, NC. In the upper part of the watershed, the river runs fast, with rocky whitewater, riffles and shallow pools, but on its path to the sea, the Neuse widens and slows. Numerous smaller streams flow into the Neuse, including Crabtree Creek, Walnut Creek, Swift Creek, Little River, Contentnea Creek, and the Trent River, connecting the Neuse with communities across its more than 6,200-square-mile watershed.

Did You Know?

DRINKING WATER

The river provides drinking water for the vast majority of the approximately 2.5 million people — a quarter of North Carolina’s population — who currently reside in the 77 established communities within its watershed.

PROTECTED LAND

Of the 3.5 million acres that comprise the Neuse basin, 48,000 acres are state parks, 110,000 acres are game lands held by the Wildlife Resources Commission, and 58,000 acres are National Forest.

RECREATION

The Neuse River Greenway Trail winds along the river as part of NC’s Mountains-to-Sea Trail that runs from the Great Smoky Mountains to the Outer Banks. The Neuse River Blueway goes past the impressive 100-foot Cliffs of the Neuse canyon.

LOCAL LORE

The Neuse flows through a remote portion of cypress swamp and hardwood forest the locals call the “LetLones.” It was thought to be so full of moonshine stills and poisonous snakes it got the reputation for being best left alone.

The Neuse meets the Pamlico Sound just beyond New Bern, the original capital of the state, founded in 1710 and a center of maritime and agricultural commerce at the time. There, the river becomes brackish with wind-driven tides, and widens to become the widest river in the country — about six miles across at the town of Oriental. At its confluence with the Pamlico Sound, the Neuse River joins one of the most productive estuaries in the country and the largest lagoonal estuary in the world.

As a quarter of North Carolina’s population live in the Neuse basin, and the river provides drinking water for most of them. These locals have been connected to the river for centuries, building a culture of fishing and boating from tubes and kayaks in the headwaters, to large sailboats and fishing boats in the estuary. Today, the watershed is home to both North Carolina’s historic agricultural and manufacturing economies and its new, robust information technology and pharmaceutical economy. The density of people, along with the diversity of industries between growing urbanized centers and critical agricultural lands, make it critically important to resolve water resource issues facing the watershed.

Reasons to Celebrate

WATER QUALITY IMPROVEMENTS

The federal Clean Water Act, signed into law in 1972, has driven most of the improvements for the Neuse River and the communities that rely on it. The Act stemmed the dumping of untreated pollution into the river and the state and communities along it rallied to the Act’s ambitious call to make the river “fishable and swimmable” for everyone.

This meant textile mills and other manufacturing had to clean up their discharges, putting a stop to the kind of pollution in the Neuse and its tributaries that famously caused it to run different colors depending on what was being dyed that day.

Recent cleanup efforts on the Neuse were catalyzed by a series of fish kills in the mid-1990s that were attributed to excessive pollution coming from sewage treatment facilities and untreated urban and agricultural stormwater run-off. This pollution created toxic algal outbreaks along the river and in the estuary that killed millions of fish.

The ensuing cleanup plans improved water quality by reducing pollution from the sewage treatment plants, including significant investments by the large cities along the Neuse, like Raleigh, which built and now operates a state-of-the-art facility.

The communities in the upper Neuse River watershed are forging a new course for improving clean water supplies and meeting the goals of the Clean Water Act. In 2015, the communities began developing the new approach based on sound science and delivering benefits to human and natural communities. The new regulatory structure reimagines the regulatory structure to stress investing in practices that restore natural function to rivers and streams and provide numerous benefits to improving clean water.

The watershed has also seen the value in protecting critical watershed lands for the preservation of water quality over the last 20 years. The upper portion of the watershed is one of the fastest growing in the nation with huge development pressures for new housing.

The state of North Carolina has invested more than $68 million through the NC Land and Water Fund (once the Clean Water Management Trust Fund) in protecting land in the watershed, and an additional $75 million restoring the river and improving clean water. A recent example: the state’s buyout of over one thousand acres of remote wilderness along the Neuse River lowlands in the Brogden Bottomlands — one of the last vestiges of wilderness in the rapidly growing Triangle. This has been supplemented by the City of Raleigh’s innovative source water protection plan that allocates $0.15 per 1,000 gallons of water used, and has invested more than $10 million to protect prioritized watershed properties. This idea has spread in recent years to other communities, with Durham also initiating investments in watershed protection in the last five years.

Coal Ash Pond Cleanup

Duke Energy constructed the HF Lee Power Station in 1951, on the banks of the Neuse River just upstream of the city of Goldsboro. The plant, which had three coal-fired units, was retired in 2012. Over its functional life the power plant dumped more than 6 million tons of coal ash into unlined pits along the Neuse riverbank. The horrific spill of coal ash into the Dan River in 2014 resulted in a renewed effort to eliminate these threats statewide, which led to closing down the storage pit on the Neuse. In 2020, an agreement was reached between Sound Rivers, the Southern Environmental Law Center and other state non-profits, along with Duke Energy and the NC Department of Environmental Quality to excavate and recycle all of the coal ash stored along the Neuse by 2035. As of April 2022, Duke Energy has removed over 400,000 tons of coal from the banks of the Neuse River.

Dam Removal

For years, antiquated dams blocked the Neuse River, harming water quality and habitat for fish and wildlife. But today the Neuse is a river reborn, thanks to the 1998 removal of the Quaker Neck Dam outside of Goldsboro and the 2017 removal of Milburnie Dam in Raleigh. These removals were triggered through the regulatory process under the federal Clean Water Act as they offset unstoppable impacts in other parts of the watershed. The removal of the dams improved water quality, creating cooler, more natural river flows. Now the river flows freely from Falls Lake Reservoir all the way to the Atlantic, making it one of the longest free-flowing rivers in the Southeast.

Work left to be done

As impressive as it is, the story of the Neuse River’s restoration is not complete. While the Clean Water Act has delivered major benefits, it still hasn’t fully delivered on its promise of fishable and swimmable waters. The added pressures from the rapid pace of development, an increase in densely packed industrial hog and poultry operations, and climate change threaten to undercut the progress that has been made.

The river and its communities experience spikes of bacterial pollution after most significant rains, as discharge from outdated septic and faulty sewage systems backflow in urban and low-lying areas, and flooded industrial hog waste lagoons and spray field runoff contaminate waterways in rural communities.

Addressing the environmental injustice of industrial agricultural practices needs to happen to fulfil the promise of the Clean Water Act. The Neuse River watershed has one of the largest concentrations of Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) in the country, rivaled only by its neighbor watershed to the south, the Cape Fear. The operations of those CAFOs have created a significant environmental injustice legacy due to the mismanagement of the waste ponds and spray fields that cause bacterial infections, polluted streams, and community disinvestment due to odor contamination. The neighbors of many of these facilities are often people of color who only see the negative impacts of CAFOs, and receive no benefits from their operation. The Clean Water Act can provide the tools to reform these practices and balance the benefits across the community.

As a result of ongoing under-regulated development, the Neuse also suffers from dirty water laden with sediment run off due to disturbances to the land around it. Too often large swaths of critical land right along the streams that feed the Neuse are being clearcut, graded and paved, and too many exceptions to environmentally protective rules are made, regularly causing them to lose their effectiveness. The conversion of green spaces to impervious surfaces from development increases the events of community flooding, not just from major storms like hurricanes, but also from the more intense seasonal storms, where more rain is dropped than can be absorbed by the land.

In the summer of 2021, two animals that are almost exclusively found in the Neuse were added to the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s list of endangered species: the Carolina Madtom and Neuse River Waterdog. Habitat surveys show that the Carolina Madtom has lost over 60% of its historical range, and the Neuse River waterdog over 35% due to increased pollution, erosion and sedimentation from developments and urban runoff.

Both species are indicator species for water quality, meaning they are the first to suffer from the impacts of significant pollution. Now that they are listed as threatened species, they will receive protections from the federal Endangered Species Act, and hundreds of miles of the Neuse has now been listed as critical habitat for their survival.

At this critical juncture in the story of the Neuse River, investments in sustainable climate resilience are critical. Over the last 10 years the river has been impacted by the most significant floods in its history, and the longest drought of record has endured over the last 15 years. Efforts to reduce flooding and improve resilience to drought cut across all the water management issues in the watershed. This has created calls for new dams to be built or other structural so-called ‘flood control’ options. Other choices that look to use natural functions to protect communities from flooding while absorbing water to reduce the threat of drought are more cost effective and provide numerous other benefits to communities and the ecology of the river.

American Rivers would like to thank our partners at True North, an Energized Sparkling Water, for their support of our River of the Year program.