The Strength of Salmon

As a species, salmon have an unrelenting, almost maddening streak of stubborn.

In the Pacific Northwest, salmon are so much a part of the landscape that their DNA is in the trees — literally.

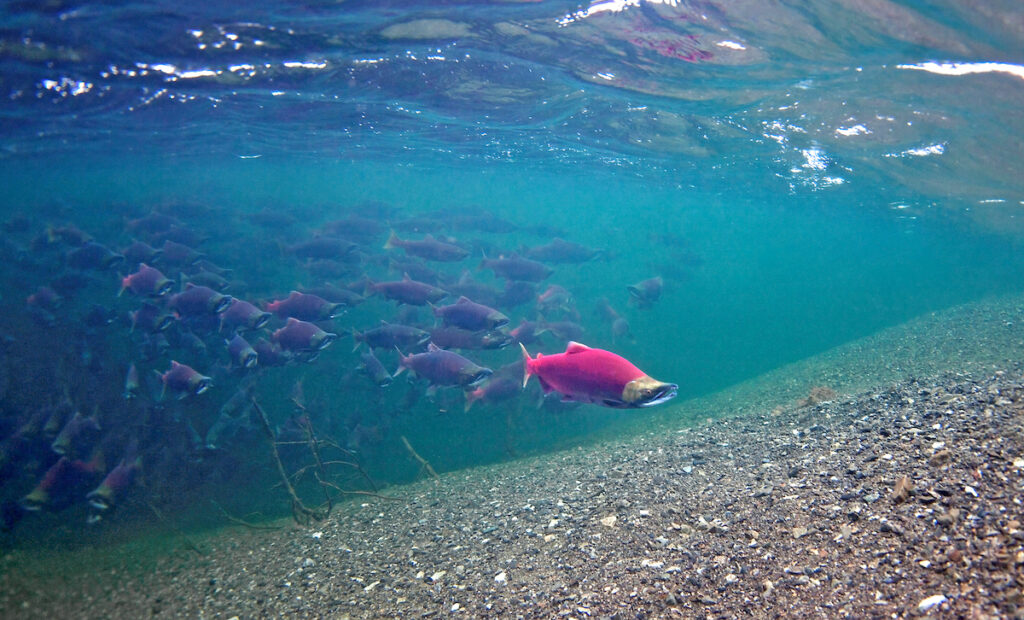

Born in the small freshwater streams of the Northwest, the smolt, or young fish, migrate out to the ocean where they transform into sleek, strong predators, gorging themselves on the bounty of the sea. How long they spend there depends on the species and the individual fish. When they return — some traveling thousands of miles — to spawn in those very streams where they hatched many years before, salmon nourish ospreys, eagles, bears, otters, people and the forests themselves. It is an inbound and outbound web of anadromous fish that has gone on for millennia.

Some studies show that more than 130 wildlife species rely on salmon as a food source. This lies at the heart of the conundrum facing rivers as salmon populations continue to decline. Let the salmon disappear, and you threaten the existence of all life up and down the food chain, including people, economies, and the Indigenous cultures that orbit these irreplaceable fish.

“Salmon are critical to the cultural lifeways of Columbia-Snake River Basin tribes, like my own people of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, Oregon,” says Alyssa Macy, CEO of Washington Environmental Council/ Washington Conservation Voters. “And they are integral to regional identity, economies, and even the orcas and the Puget Sound.”

An “extinction vortex”

A 2020 report from the state of Washington described the plunge of salmon populations as a crisis, citing both climate change and habitat loss as the primary culprits in that downward spiral. Of the 14 endangered species of salmon in the state, 10 lag in their recovery goals. Five species are in dire straits.

Throughout the Northwest, the decline of salmon has reached critical levels. In the Columbia Basin at large, salmon have become a mere whisper of their historical selves. Once home to the largest salmon run on earth, 30 million strong, rivers of the Columbia Basin now host only 1.5 million individual salmon per year. And just 400,000 of those are wild fish.

A Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) study on migratory fish, published in the spring of 2021, found that wild Snake River Basin populations of spring and summer Chinook were declining 19 percent every year, putting 77 percent of populations close to extinction by 2025. Historically, the Snake River Basin was the major producer of salmon and steelhead in the Pacific Northwest.

Climate change + dams = deadly for salmon

The threats facing salmon are as complex as the natural web salmon help to weave. First in line, as with so many species, are the threats posed by a changing climate.

Lower snowfall averages mean less water for everyone. Less water plus higher summer temperatures equal lethal conditions for fish. Warming ocean temperatures also impact the availability of marine food at a time in salmons’ life when they should be theoretically bellying up to the buffet, packing on pounds and muscle that will serve them in their massive migration to spawn. Hobbled by heat and hunger, disease and predators get the upper hand.

Dams make the problems ever more dire: Dams block adult salmon from migrating back to their historic spawning beds. Salmon that can’t migrate can’t procreate. Plus, the stagnate water in reservoirs held behind dams become hot bathtubs — a deadly recipe for outgoing smolt.

For Snake River salmon, four federal dams and reservoirs in eastern Washington kill up to 80 percent of juvenile fish. If the four dams remain in place, global warming could push the Snake River’s remaining wild salmon runs to extinction.

Even with such obstacles, there is room for hope. If we were to anthropomorphize salmon, it could be said that the entire species is characterized by a strong, unrelenting, almost maddening streak of stubborn.

Put another way, if you give salmon half a chance, they’re going to take it and — literally — run.

Salmon will return to healthier rivers

Take for example the restoration of the Elwha River. After decades of work, the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, American Rivers and other partners succeeded in authorizing dam removal and securing federal funding for the Elwha River restoration project. Elwha Dam removal began in 2011, and the river was fully reconnected with the final blast to the Glines Canyon Dam in 2014. Almost immediately there were salmon. Hundreds of thousands of them. The Elwha is on track to surpass 400,000 fish in the next 30 years, putting it back on track with historic run numbers.

The opportunities to restore Northwest salmon populations are numerous. Here are two that top the list.

Snake River: Tribes are advocating for the removal of the four federal dams on the Lower Snake River in eastern Washington to honor treaties and restore healthy salmon populations. Restoring a free-flowing lower Snake River would be the biggest river and salmon restoration effort in history.

“We view restoring the lower Snake River as urgent and overdue,” said Nez Perce Tribe Vice Chairman Shannon Wheeler. “To us, the lower Snake River is a living being, and, as stewards, we are compelled to speak the truth on behalf of this life force and the impacts these concrete barriers on the lower Snake have on salmon, steelhead, and lamprey, on a diverse ecosystem, on our Treaty-reserved way of life, and on our people.”

It’s now or never for meaningful action to recover the Columbia and Snake basin’s iconic wild salmon and steelhead runs and invest in the region’s future. American Rivers is supporting calls from Native American tribes across the region to remove the dams, and we named the Snake America’s Most Endangered River in 2021 to draw national attention to the issue.

Klamath River: On Oregon and California’s Klamath River, the Karuk, Yurok, Klamath and other tribes have led the effort to remove four dams to bring back salmon runs and improve water quality. Dam demolition is scheduled to begin in 2023.

“My worst day as chairman is when I said there were no fish available for our tribal members, our elders, our children,” says Karuk Chairman, Russell “Buster” Attebery. “I’m looking forward very much to having the best day as chairman of the Karuk Tribe when I can say we have restored those fish and we can enjoy those bonding times with our children, when we can go to the river and put the food on the table together.”

“We hope it is a benefit to everyone. Everyone who comes into contact with the Klamath River. Everyone who lives close to the river who wants to vacation here, the farmers and irrigators who live in the upper basin. We want to make sure there is enough water for everybody. Working together, we can do that.”

Salmon are truly one of the planet’s most incredible creatures — and they rely on healthy, clean, free-flowing rivers. We must do all we can to ensure the survival of both.

4 responses to “The Strength of Salmon”

Leave the lower Snake dams alone.The three dams in Hells Canyon are the problem.When the dams we’re put in ,the Weiser,Boise,Payette,Malhuer,Owyhee and Powder rivers were blocked off.

At one time the Salmon and Steelhead runs were the biggest outside of Alaska.Every body of water, no matter how small had fish in them.

The Native Fish Coalition, Maine Chapter, is a start…

https://nativefishcoalition.org/maine

I know your focus is on the western part of the country but perhaps sometime you could do something with restoration efforts of the Atlantic salmon. And as a bonus, they live after spawning.

Finally, Nevada Irrigation District promises to allow fish passage at the Hemphill Dam site in Lincoln, California. How wonderful will be to witness the return of salmon in the Klamath River….