Fire, drought and the Colorado River Headwaters — a photo essay

After the COVID daze of the last year and surreal summer of fires the Upper Colorado endured last year, I felt compelled to actually go out and document what was happening, essentially in my home space.

This is a guest blog by Boulder, CO based photographer Tim Romano. All images were taken by him. All rights reserved.

For decades, I have been exploring and photographing the Upper Colorado River and its tributaries. Not for any reason other than I love the watersheds associated with it, have grown up on them, and truly feel connected to these trickles of water. I literally can’t help it. As a photographer and river rat it’s always been something I’ve done. For fun…

Yet something this spring changed for me in that regard. After the COVID daze of the last year and surreal summer of fires the Upper Colorado endured last year, I felt compelled to actually go out and document what was happening, essentially in my home space.

It’s hard to put into words, but after a spring of running river miles by floating the San Juan, main stem of the Salmon, Gunnison, Arkansas, Roaring Fork, multiple small tributaries on the Front Range, and the Colorado I realized I was actually chasing something. Something deeper than simply the next great shot, or the next slick run through roiling whitewater, I literally was chasing the future of my home, and the home of my little girls.

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Southwest for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

For the first time in my life, I felt like I was doing it for something beyond just thrills. A certain truth set in for me this year as my home river was reduced to a mere trickle, smoke filled the air every day for a second or even third summer in a row, fires started, and water temperatures approached the mid-seventies. This is how it’s going to be. Maybe for the rest of my adult life and my kid’s as well? That’s not to say things can’t be done to reverse some of the damage, but throughout this summer I’ve felt like I must see and do as much as I reasonably could with the river. If I was invited on a permit, I said yes. If I could squeak in an extra lap on the St. Vrain after work, I did. If I had to drive four hours to fish a bit of river I’d never seen, I went.

In early July, a commercial photoshoot of mine was canceled due to smoke. I had already booked the time (a few days,) rented some gear, and had my camping stuff packed. I was frustrated, mad, and sad all at the same time. Instead of just moping and being angry, I decided that it would be cathartic for me to go see some of the fire damage from last year and experience what was really happening on some of the drainages that feed the Colorado. My need to document what’s going on was strong. So I went. It wasn’t necessarily uplifting, and the reality of the situation certainly hurt. But I had to share. Maybe you’ll find it depressing, educational, or somehow perhaps it will inspire you to take note of what’s going on, and maybe find something within you that you can do – for the river.

The extent of the devastation from the East Troublesome fire that ripped through much of the Colorado headwaters is like no fire scars I’ve ever seen. In one day the fire burned 120,000 acres and in total destroyed 193,812 making it the second largest in Colorado history. This image was taken just west of the Kawuneeche Valley in Rocky Mountain National Park.

Smoke has filled the air almost every day this Summer and sadly has become so normal that it just seems like a part of life now on the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains. This image is from the top of Independence pass next to one of the nearly dried up feeder streams to the Roaring Fork river – a tributary of the Colorado.

The inflow at Highland Marina is basically non-existent as plants start to take hold on what was once the bottom of Lake Granby. One can almost walk from one side of the bay to the other without getting wet. The lake is the third largest body of water in Colorado and is a major storage reservoir for the Colorado river.

A backhoe pushes the dock store further out into what’s left of Lake Granby and backfills with dirt to make sure people can access it from the water. The background shows damage to the trees from the East Troublesome Fire which basically burned a good portion of the West side of the lake.

Thick smoke fills the air over the dewatered Roaring Fork River near Glenwood Springs while swallows take to the air consuming grasshoppers that are emerging months earlier than normal this year.

The “mighty” Colorado next to I-70 in Glenwood Springs is deeply discolored from fire-caused mudslides in Glenwood Canyon. There’s real concern that these heavy loads of sediment will not be easily washed away as lingering low flows year after year persist, smothering bug life and coating the bottom of the river with thick muck.

A lone trailer sits empty near the nearly dewatered confluence of the North Fork of the Gunnison and and main Gunnison Rivers earlier this summer. The North Fork’s flows were about 10 CFS (Cubic Feet per Second) and temperatures were approaching 80 degrees. Driving into the Gunnison River valley makes you realize that green wouldn’t even be a color on this thin ribbon of land if it wasn’t for this important artery of the Colorado.

Raft guides and clients walk a boat out of the sediment laden waters of the Colorado at the Grizzly Creek Rest Area in Glenwood Canyon on the Colorado, where a 36,631-acre fire that burned almost the entire canyon occurred, burning from August 10th until December 18th, 2020.

A lone raft launches from the Shoshone put-in on the Colorado. Since this image was taken several, 100 & 500 year rain events have coursed through the burn scars, completely covering both the highway and across the entire river, altering rapids and pumping thousands of cubic feet of mud and debris into the river.

A soiled and sad Colorado River below the dam that holds water for the Shoshone power generating station. Shoshone holds senior water rights to more than 1,250 CFS, pulling water from the headwaters of the Colorado westward, but sometimes dewatering this short stretch in Glenwood Canyon.

A quick stop on a misty evening on the top of Independence Pass en-route to a float can sometimes trick you into thinking all is fine down valley with low clouds, moisture and rain cascading down to the river.

Water clarity in the headwaters of the Colorado River seem to be more this color than anything else, after the fires of last year and monsoonal rain events that have followed this summer.

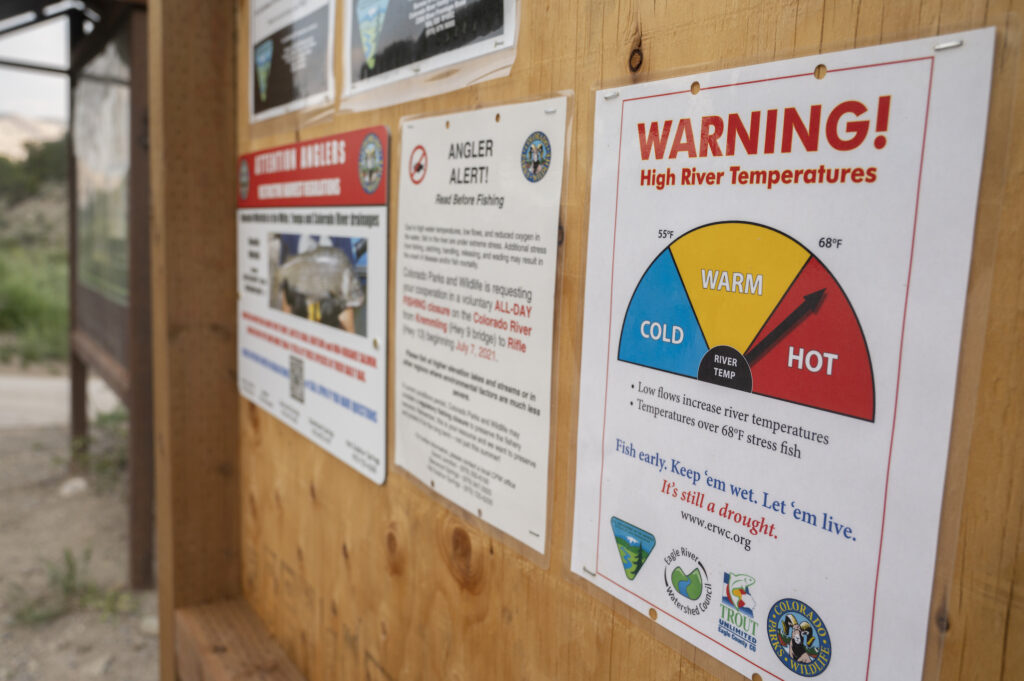

These signs were posted in early June on the upper Colorado. On June 14th, A gauge far upstream of these read 73.76 degrees and a mere 335 CFS of water. During what should have been a raging runoff on the Colorado river.

Riverbanks have looked like this a lot the past few years and I suspect we’re going to have to get used to seeing a lot more of them going forward.

Whitewater enthusiasts may also have to get used to changing landscapes like this one in Glenwood Canyon. Not only is a burnt forest an eyesore, it holds serious complications for the watersheds, infrastructure, and outdoor recreational enjoyment that they once anchored.

It’s never a good sign when plants are growing on mid-stream sandbars in early July. The Upper Colorado River just upstream of Lyons Gulch, one day after a water call bringing the water up from what was about 400 CFS, making what would have been a frightening trickle look almost normal.

Newly installed and updated boat ramps covered in sediment and in some spots becoming almost unusable due to the ongoing low water situation.

A muddy and critically low Colorado river above the Horse Creek Launch shows the disparity of who has water, how it’s used, wasted, and what the land would look like if the water disappeared.

After enduring one of the longest and most severe droughts in recorded history – a length that legitimately amounts to a good portion of my adult life here in the West, I’ve come to realize this isn’t going away. We can do our snow dances, pray for rain and use our magical thinking skills to try and fix it, but the reality is it’s going to get worse. The science says so, and as an observer of the outdoor world I can feel it and see it happening year after year.

It may ebb and flow. We might have some big water years coming up, but more than likely we’re going to be dealing with lots of low water, fires, dewatered reservoirs, and rivers that we once knew – changed for good. As water lovers we all either better be really good at not caring, do what we can now to save what’s left by conserving, or straight up adapt to what’s left. The new reality is here now, and sadly it’s not likely to get a whole lot better soon. Unless we all lean in, and act.

2 responses to “Fire, drought and the Colorado River Headwaters — a photo essay”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DRlGOutxaYg

These images are of my home. Literally.

Sadly, you did not do it justice. Troublesome, yes. Paradise also.

Next time make an effort to capture the beauty of hosting a fury, and not just the simple superficial of what, in my artistic opinion which is professionally known as excellent, reads to me as “band-aid” art.

Sticky, pale and simply the plastic that covers the true reds and blacks of wounds made holy through the apparition of maps of scars charting the route of a journey given, not asked for. Blessed proof of miracles endured, no less worthy of worship than that of the stigmata of Jesus Himself.

Thank you for putting the band-aid on this burn.

Next time, please do this hollowed ground the favor of being brave enough to finally rip it off. Don’t worry, it won’t hurt much. She’s definitely been through much worse.