Heat + drought strike Southeast rivers and communities…again

Welcome to the era of “hot drought.”

It was the summer that felt like it would never end. Here in Atlanta, we had a nearly unbroken heat wave through August and September, with record-high daytime temperatures steadily hitting the mid-90s. Fall has finally arrived, bringing cool temperatures and even a little rain—but the drought conditions that arrived in force in September remain with us.

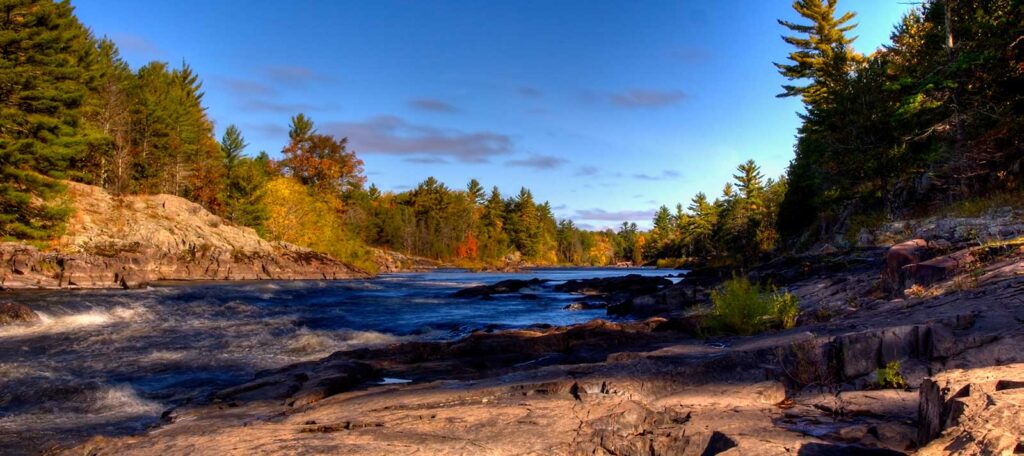

In fact, overall it has felt a lot like fall 2016, when wildfires raged over large swaths of the north Georgia mountains. That year, for much of the state, the rain quit in about May. This year, the weather really started drying out in north Georgia in late August. But conditions have been largely similar: hot and dry, with rivers and reservoirs dropping fast. The upper reach of the Flint River here in Georgia dropped quickly to very low levels just like in fall 2016—and lower than the river had been in any recorded droughts before 2000.

Welcome to the era of “hot drought.”

Hot drought is the deeply concerning phenomenon that increased temperatures exacerbate the impact of drought. It is natural for water to be lost from the landscape into the atmosphere. But the many ways in which this occurs are amped up in a hotter world. For example, hot sun bakes the moisture out of surface soils and (during the growing season) draws more water out of plants through transpiration—plants’ process of “breathing” water out through their leaves.

In some climates (not Georgia!), hot drought accelerates snowpack melt. And in many places, Georgia included, hot drought results in increased evaporation of water from reservoirs, rivers and wetlands. In fact, in the middle of September a municipal water provider in the upper Flint River basin here in Georgia startled me by reporting that one of his reservoirs had lost 6 inches of elevation in three days—all of it from evaporation. Yikes.

Unfortunate Vanguard

In fact, yet again the communities of the upper Flint River basin find themselves in the bullseye of oncoming drought. Although currently rainy weather might alleviate drought conditions, two communities in the basin are the only communities in the state currently at “Level 2” drought response, enforcing constraints on outdoor water use beyond the standard schedule in Georgia state law. (Much of the state moved into to “Level 1” drought response with a recent State of Georgia announcement.)

The upper Flint River basin, thanks in part to its heavily developed headwaters area and with many communities depending on the river system for water supply, often feels the brunt of drought conditions earlier than the rest of the state. That’s why American Rivers has worked with water providers throughout the basin since 2013 to be sure we’re all communicating about oncoming drought conditions, and to find ways to balance the water needs of communities with the water needs of the river itself.

Similarly, next-door in the Carolinas, we’re helping communities use the precious water we do have more wisely, and making sure all voices are heard when it comes to decisions about our water supplies. Because everyone deserves a future of ample clean water and healthy rivers, year in and year out.

An Uncertain Season

This fall’s conditions in the Southeast are being called “flash drought,” because of the quickness with which the recent hot weather dried out the landscape. Plants show a flash drought, badly and quickly. And as I’ve watched the river drop, it makes me think about the warnings we hear from climate science, the impacts of a warming world on our rivers and water supplies.

It is hard to say how long our newest Southeastern drought will last. Will we get good rain this winter, and start off next spring in better shape? Will this be a one-year affair, like 2016-17? Or will this be a three-year deal, like in 2006-2008, when Metro Atlanta was counting the days of water supply remaining in the Chattahoochee River’s Lake Lanier? Or could it be even longer?

That’s the thing about drought: We know when we’re coming into another one, but we don’t know how long it will last. Our extra-long summer heat wave has ended. But the drought outlook for the rest of this fall is not clear. Even with recent rains, it will be a little while longer before we know just how long our newest drought—hot or not—will last.