The new Colorado River drought plan is an important first step

An increasingly arid Southwest isn’t something we can control. But surviving it with enough water is.

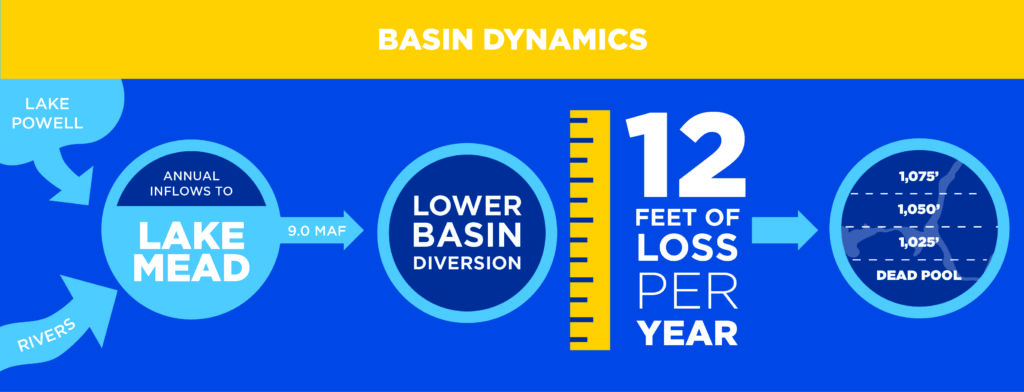

The ominous bathtub rings in Lakes Mead and Powell are evidence of the most serious challenge facing the seven U.S. states that depend on water from the Colorado River. The bands of blanched rock, several stories high, tell the story of the nation’s largest two reservoirs in crisis, and a Colorado River that’s steadily losing its ability to meet all the demands placed upon it.

Falling Lake Mead levels threaten Arizona and California water supply

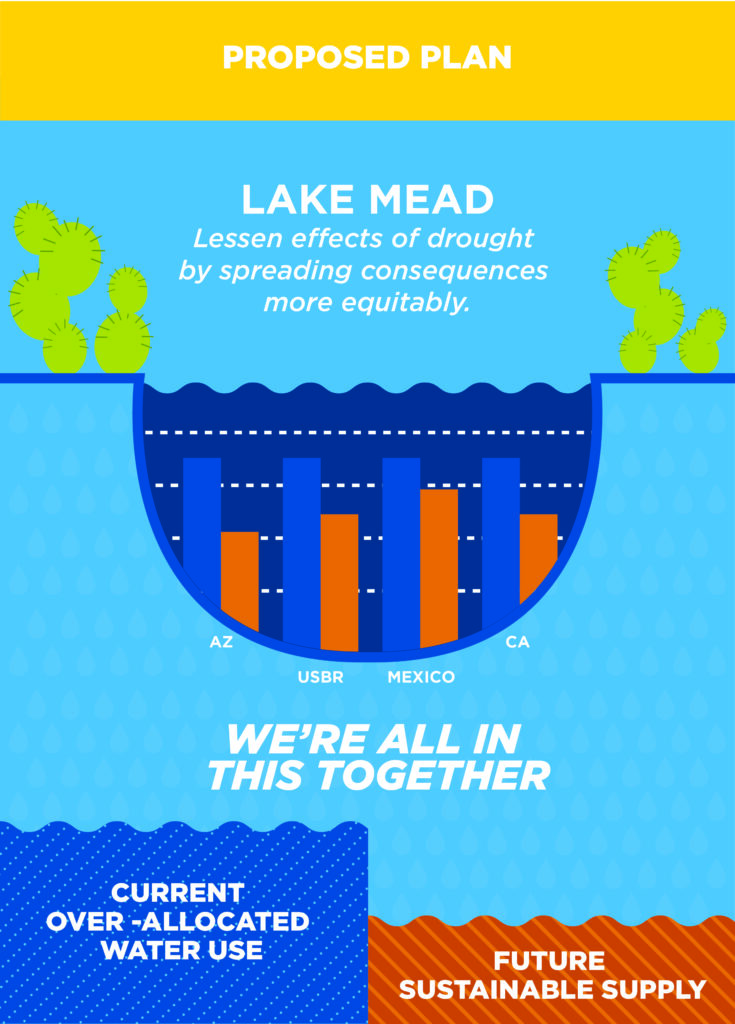

Earlier this month, after years of fitful effort, state agencies and water providers agreed on a Drought Contingency Plan to deal with the very real possibility of shortages in the water supply provided by the river. This tentative agreement is big step toward slowing the decline of Lake Mead and setting up a future of more sustainable water use in the Colorado River Basin.

On the positive side, the tentative agreement creates a framework to save more water in Lake Mead in coming years and to allocate the supply cutbacks that will accompany the nearly inevitable shortage.

According to the Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency which oversees management of the river system, there’s a nearly 60 percent chance that a “Tier 1” shortage will be declared in the Lower Basin states (California, Arizona and Nevada) in 2020. The goal of the Drought Contingency Plan is to prevent even deeper cutbacks in the future supply available to the Lower Basin.

Lake Powell: Photo credit Rainer Krienke

A successfully implemented Drought Contingency Plan will reduce the risk of deeper shortages. It is our best chance to avoid significant cuts to Arizona’s water supply.

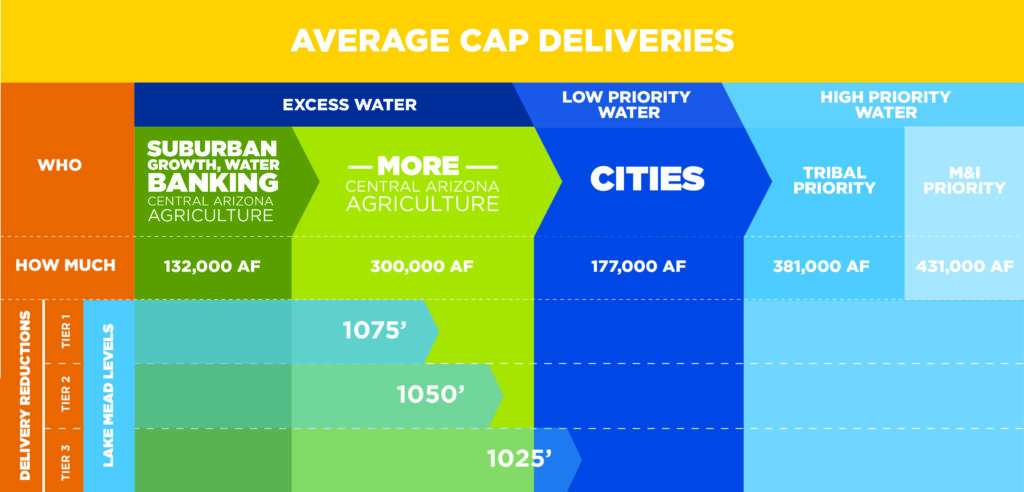

From the moment a Drought Contingency Plan is formally signed, central Arizona will have to live without 192,000 acre feet of water per year. (One acre foot is enough water to cover a football field 1 foot deep.)

It’s also likely that the federal government will declare a “Tier 1” shortage in 2020, forcing a cutback of 512,000 acre feet of water per year, or nearly 30 percent of Arizona’s annual Central Arizona Project supply. Without an Arizona agreement on how to equitably allocate this cutback, shortages on the river will likely deepen, forcing the state to forego an additional 128,000 acre feet.

Right now, all of this water is used by farms in central Arizona, the new subdivisions sprouting up around the Valley of the Sun, and homes and businesses in cities around Phoenix. Protecting people and farms while securing the future of the river is a difficult challenge and must be done in an equitable way within established laws and priorities.

Looming shortages will cut deeply into water available for Arizona

But the Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan only gets us so far. It provides the river community with breathing space to tackle the deeper problems facing the Colorado River and its communities — including the original over-allocation of the river’s water; over-consumption by farms and cities in California, Arizona and Nevada; and the intensified aridification of the region caused by climate change.

Ever-shrinking water levels in the Colorado River Basin aren’t short-term hiccups in hydrology and precipitation. They are the inevitable result of long-term forces that will require bold action to alleviate.

A collaborative Drought Contingency Plan reduces risk to Arizona and Colorado River

This month’s agreements will help get river communities through the near-term shortages that seem inevitable, and they are an important first step toward more lasting solutions. In the next few years, river leaders and water managers have an opportunity to build on the Drought Contingency Plan and to think ahead. Protecting the river and the water it provides will require us to develop resilient solutions that reduce water consumption and efficiently share the river’s waters.