Pulling the Wool Off Our Eyes: Restoring Wilderness Meadows

Historic overgrazing damaged Sierra Nevada meadows and the impacts of overgrazing can still be seen today, even in wilderness areas thought to be pristine. American Rivers is partnering with the National Park Service in restoring meadows in headwater regions in California to make our water supply more resilient in the face of climate change.

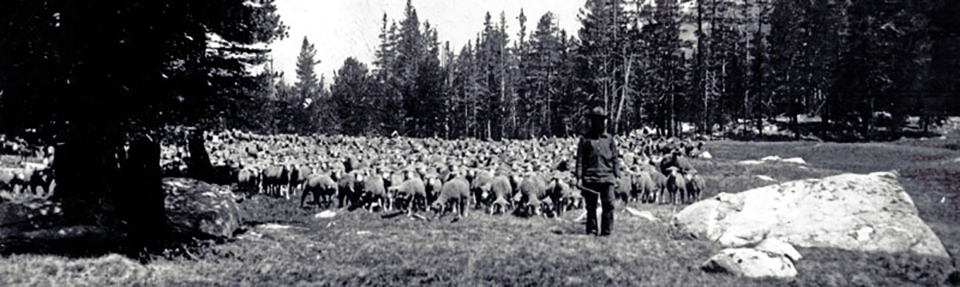

“The Kern Plateau, so green and lovely on my former visit, in 1864, was now a gray sea of rolling granite ridges, darkened at intervals by forest but no longer velveted with meadows and upland grasses. The indefatigable shepherds have camped everywhere, leaving hardly a spear of grass behind them.”

– Clarence King, a member of the Whitney Survey in search of the highest peak in the United States

This past summer, the headwaters team in California was busy assessing wilderness meadows in Kings Canyon National Park. On our last six-day backpacking excursion, we waded through remote meadows perched at 9000 feet, a rugged four miles as the crow flies from the closest trail and ten miles from the nearest potholed dirt road. Throughout the trip, I couldn’t stop wondering about the shepherds and their flocks whose legacies still haunt even the most remote glacially carved canyon in the Sierra. I marveled at their fortitude; lacking such modern luxuries as GPS units, Gore-Tex hiking boots, and titanium trekking poles, these rugged mountain men navigated nearly every nook and cranny in the Sierra Nevada. Though the extreme lengths these shepherds went to are impressive to the modern backpacker, the ecological legacy of sheep grazing is less than admirable. Many Sierra meadows are in poor shape because of the shepherds and their sheep.

Why flock to mountain meadows?

Why did the shepherds traverse rivers and ridges high in the Sierra Nevada in search of remote meadow pastures? A series of floods and droughts from 1862-1864 drove shepherds from the southern San Joaquin Valley to look for higher pastures in the mountains, desperate for a reliable source of forage for their animals. As California’s population grew, so too did the demand for meat. Peak grazing in the park occurred from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s. The transhumance – the movement of livestock from one grazing ground to another in a yearly cycle, from lowlands in the winter to high mountains in the summer – became an established tradition in the Sierra for nearly a century. Even after grazing was banned when Sequoia and Kings Canyon became a jointly operated park in 1940, the impacts of overgrazing are visible today.

Meadows Today

California’s mountain meadows act like sponges – absorbing water during the wet season and slowly releasing it over the dry summer and fall months. In the context of climate change, meadows are an essential component of California’s water supply. As years go by and climate change continues, Californians will likely see less and less snowpack in the Sierra Nevada. Thus, our state will be ever more reliant on healthy meadow systems that act like water reservoirs. In addition to being critical for our future water supply, meadows are biodiversity hotspots and a valuable aesthetic resource.

Why Are Sheep So Baaad?

Overgrazing fundamentally alters how water flows in meadows. In healthy systems, wide stream channels slowly meander through the meadow. However, when meadows are overgrazed, sheep trample stream banks and wipe out the vegetation that stabilizes soil during spring flooding. Without vegetation to anchor down soil, there is widespread erosion and gullying of the stream channel. Once erosion takes hold, spring floodwaters no longer spread out across the meadow surface. Instead, the downcut channel concentrates the energy of high flows, causing a continuous cycle of degradation. When meadow streams incise meadow soils, forming narrow deep channels, the meadow surface dries up. Unhealthy meadows have decreased value in terms of biodiversity, water storage, and aesthetics.

The Role of American Rivers

AmeriCorps member Rachel Friesen and American Rivers volunteer Carson Clark measure a large gully as part of a meadow assessment in Kings Canyon National Park. | Maiya Greenwood

The American Rivers team in California is excited to be partnering with the National Park Service for the first time. Our California Headwaters Conservation team is in the process of performing meadow assessments in order to prioritize wilderness meadows for restoration. Over the last summer, our team has trekked many miles across boulder fields and through aspen thickets to access meadows in remote reaches of the Sequoia-Kings Canyon Wilderness. Currently, we have completed 42 out of the 50 meadows that we aim to assess by 2018. Following the initial assessment phase, we will continue to partner with the National Park Service by piloting meadow restoration techniques that are appropriate in wilderness areas.

We hope to pull the wool off our eyes and not be fooled into thinking that remote wilderness meadows are inherently pristine. Here at American Rivers, we know that some systems are not resilient enough to recover on their own; many wilderness meadows need both time and active restoration efforts to heal after a century of overuse.