A River with a Fever Threatens Native Salmon

The Lower Green-Duwamish River is getting too hot for salmon to survive. Counties and cities in the Green-Duwamish watershed must do more to revegetate the river for the health of salmon and local communities.

This post by American Rivers’ Lapham Fellow, Jonathon Loos, is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Green-Duwamish River.

In Western Washington, the Lower Green-Duwamish River has a severe temperature problem that is jeopardizing the sustainability of native fish populations.

The Green-Duwamish watershed is home to native populations of Chinook, chum, pink and coho salmon and steelhead trout. These fish use the lower river as a migration corridor when heading to the Puget Sound as juveniles, and again as adults returning upriver to spawn and reproduce where they were born.

This Green River Chinook salmon died before she could mate and lay her eggs. A pathology exam found evidence of a bacterial disease known to thrive in warm water. | Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

Historically, the Green-Duwamish River supported populations of salmon large enough to feed generations of Native Americans. Today, this is not the case, as Green River Chinook salmon and steelhead populations have declined and are listed as Threatened Species under the Endangered Species Act. Unhealthy temperatures have likely contributed to the declines in native salmon stocks. Warm water holds less dissolved oxygen, which leads to stressed fish and promotes outbreaks of warm water-related bacterial and parasitic diseases in salmon and trout. These factors can create enough conditions to kill fish as they migrate upstream. Instances of pre-spawn mortality have been observed for Chinook; this is an enormous loss after salmon survive such a long perilous journey from egg to adult— from river to the ocean and back again.

Federal and state governments are tasked with defining healthy water quality standards for fish and people. The Washington State Department of Ecology defines the healthy maximum temperature threshold for the Lower Green River to be 63.5 °F. However, daily summer temperatures in the Lower Green River typically reach 70-72°F, and sometimes even exceed 74°F, a lethal temperature range for cold water fish like salmon and trout. In fact, in July 2015, the temperatures observed exceeded the lethal threshold at almost every mainstem location sampled in the lower 45 miles of the Green-Duwamish River (Green-Duwamish River 2015 Temperature Data Compilation and Analysis (Draft), King County).

Engineering Away Cold-Water Habitat

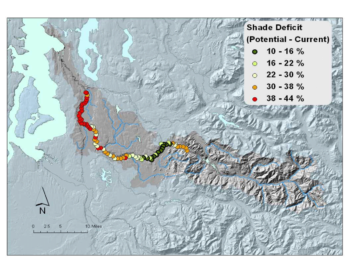

Much of the Green River is bordered by parking lots and asphalt trails. This figure shows the effective shade deficit by 1,000 m increments. The deficit is the difference between the mature riparian shade condition (i.e., lots of trees) and the current riparian shade condition (i.e., lots of roads and buildings). | Washington Department of Ecology

The Green-Duwamish’s heat problems are a consequence of development and flood-control infrastructure that has constricted the river channel. Over the past century, the Lower Green-Duwamish watershed has developed into a thriving hub of urban and industrial development. As a result, buildings have encroached on the river and squeezed out space for trees and riparian vegetation. Levees and concrete riprap have been installed along much of the Lower Green-Duwamish, intended to provide protection from floods and reduce erosion hazards. As river channels and floodplains are urbanized and engineered into controlled waterways, the natural processes that regulate a river’s water temperature become lost; riparian and forest shade is removed and cool groundwater exchange pathways are disrupted.

The middle and lower sections of the Green-Duwamish River need more shade. Development has led to few trees on riverbanks and increased water temperatures. | Washington Department of Ecology

Only a fraction of the lower 30 miles of the Green River has adequate riparian shade. Mature native trees, such as cottonwood, fir, maple, alder and willow, are cut down to accommodate levee construction and repairs. Rules set by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers restrict the growth of vegetation along levees and require their continual removal or pruning as they mature. While some trees have been planted to mitigate levee work, these plantings sit on benches that are often less than 10 feet wide— too narrow to support a robust shade-giving stand of trees and riparian growth. In an effort to comply with levee maintenance policies, local levee sponsors often remove planted trees before they mature.

As the influence of climate change intensifies, the Green-Duwamish’s degraded riparian habitat and harmful temperature conditions will persist or worsen until riverside management practices are changed. Salmon are resilient creatures, but they will not survive in the Green-Duwamish unless riparian shade is restored along the river.

What Needs to Happen

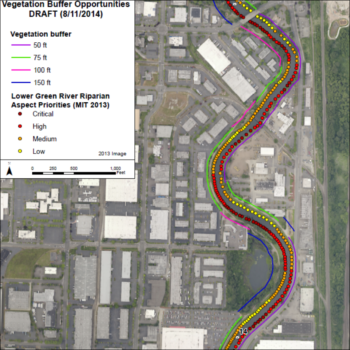

This is an example of a Sun Map, which shows potential vegetation buffer widths based on existing land use constraints. | King County, Washington

In 2011, the Washington Department of Ecology issued a call to action for local governments and citizens to help reduce water temperatures in the Green River watershed. The two top actions identified were: “Protect and restore streamside vegetation” and “Plant tree borders”. Unfortunately, very little action has been taken since the report was published five years ago.

Recently, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and King County have been working on the Green River System-Wide Improvement Framework— a plan to advance flood risk reduction in the lower Green River. As part of that effort, the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Fisheries Division prepared “Sun Maps” to prioritize areas of riverbank where trees would be most effective in shading the river based on solar aspect (see Appendix G). That mapping effort was first completed in 2013 and presented a clear analysis of where shading is needed most. However, the combined influence of the Sun Maps, water quality regulations, and the listing of Puget Sound Chinook on the Endangered Species Act has not spurred the full level of action needed.

The King County Flood Control District, together with the cities of Kent and Tukwila, are choosing floodwalls and rip-rap bank armoring instead of sustainable levee designs that provide room for trees to shade the river. Image: Floodwall on Boeing Levee, completed 2013. | City of Kent, WA

King County hosts a grant program called “Green the Green” that promotes voluntary efforts by cities and private landowners to plant trees in riparian areas. However, funding for the program is lean and progress is likely to be slow unless the Green River’s health becomes a much higher priority for everyone, including the cities of Kent, Auburn and Tukwila, and the King County Flood Control District. Programs must be designed to encourage riparian landowners to maintain streamside buffers with native riparian vegetation and trees. Concurrently, new levee designs are needed that incorporate space for riparian buffers. This could be achieved through the inclusion of a wide and gently-sloped tree and riparian planting area on the riverside of levees, or by setting levees further back from the channel where possible.

Restoring riparian shading along the lower Green will not come at the cost of greater flood risk to people and property. In addition to shading the river, trees’ roots hold onto soils and slow bank erosion, provide habitat for birds and small mammals, and create green landscapes that improve the aesthetics, and even health, of urban residents and workers.

Moving Forward

We need to remind our decision-makers that implementing riparian vegetation and levee design solutions that support the ecological integrity of the Green-Duwamish River must be a priority. Investments in functional riparian buffers and multi-benefit levee projects promote the health of our ecosystems and our communities. If you live in the Green River watershed, please take the time to contact your County Council representative, mayor, and city council members and tell them that flood control plans need to do more for the Green River.

4 responses to “A River with a Fever Threatens Native Salmon”

I am suspect of that river crossing- living about an eight of a mile upstream, I have seen in the early morning some sort of truck with a big pipe on the back pumping something into the river

I took a 40 hour Duwamish Superfund clean-up course offered by the Federal government four years ago.

It was a joke- the whole course was supposed to encourage minority participation in the cleanup training, and out of 200 people who showed up and were tested for two days 15 were selected

Only two were racial minorities, and those two were 65 and in no condition to do physical labor

The course was absurd- two days of classes on race (silly) and then hours and hours of just reading the text

the instructors were nice guys but no experts in clean-up of a waterway

After two months only one person was hired by a cleanup company, but for machine repair, which he already knew before the course

Three months later they announced the planned superfund cleanup was cancelled due to funding cuts

“this is an enormous loss after salmon survive such a long perilous journey from egg to adult— from river to the ocean and back again.”

The salmon are us. We are the salmon.

Thank you for doing this important work!

Interesting! I hadn’t thought much about the impact of shade on our rivers before. Keep up the good work!

I was in Green river area, near Van Doren’s Landing Park.

The sewage smell was pretty noticeable. I am not sure how water treatment works.