I was standing along my local river the other day, under a blue sky with a gentle breeze slipping by. Soft sunlight from above reflected off the nearby cliffs and a muted silence surrounded my thoughts – rare for a beautiful Sunday morning in August. Normally there would be kayakers surfing the wave at Smelter, and kids hopping around chasing striders by the water’s edge, and cyclists zipping by on the bike path behind me. But it was silent. Eerie.

By now you have certainly seen the news about the tremendously tragic, toxic release of abandoned mine waste into the Animas River near Silverton, Colorado.

More than 3 million gallons of toxic sludge were blown into Cement Creek, a key headwaters stream to the Animas, turning the river bright orange and sparking a loud outcry of rage, blame, and sorrow.

But unfortunately, this accident has been waiting to happen for decades, as this particular mine was closed in 1923, left abandoned by the mining operators for the public to clean up generations later. This is exactly what the EPA was beginning to do when the release was triggered. Much blame has been laid at the feet of the EPA, and they have expressed their apologies and commitment to address the immediate mess as urgently as possible. But it is really the toxic legacy of abandoned mines, and just within the area surrounding Silverton in San Juan County, there are over 1,100 of these sitting idle, that is the real story.

How much longer will these abandoned mines continue to leach their poisonous legacy into our streams? How much longer will they impact fisheries, agriculture, and the communities that depend on these rivers for their core viability?

In fairness, it’s not like there are floor plans available for the more than 4,000 abandoned mines in Colorado alone. Much work must be done to reduce or eliminate the toxic legacy of mining effluents running into our streams every day, and we hope that this effort will take on an even greater degree of urgency after this tragic event.

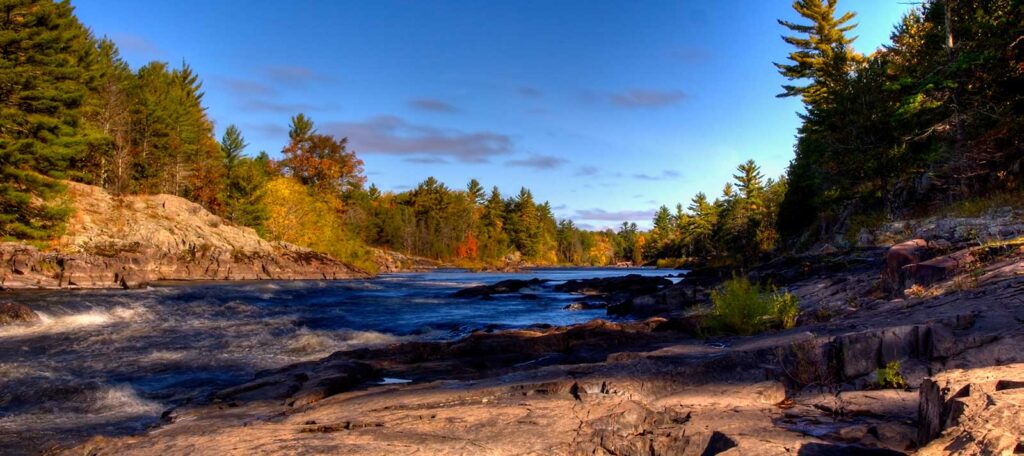

Animas River, CO, after a toxic mining waste spill

It also signals a need for even greater vigilance in protecting our rivers – especially the last remaining pristine rivers across the country, like the Smith River in Montana. Named as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2015, the Smith is cherished by Montana residents and river runners and anglers from across the country, as one of the last, best places to experience a true escape from the pressures and pace of a fast-moving world. It also is a sustainable economic engine, generating over $4.5 million per year in tourism and jobs in central Montana.

Half of the rivers we named in this year’s Most Endangered list are threatened by mining: the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, Montana’s Smith River, Alaska’s Chuitna River, Oregon’s Rogue River, and Minnesota’s St. Louis River. Industrial scale mining can have devastating and permanent impacts and we must mobilize public action to protect clean water and river health.

American Rivers is actively working to protect places where mining is proposed, and we will remain dedicated to the idea that it is unacceptable to put our river economies, river heritage, river recreation, and clean water for people and natural communities at risk.

I don’t want to see another river somewhere else in Colorado, or anywhere else in the country, suffer the same fate as the Animas. Let’s get to work.