Penobscot River

Ancestral homeland in Recovery

Before the 1830s, there were no dams on Maine’s Penobscot River. Atlantic salmon ran upstream in schools numbering 50,000 or more. Shad and alewives migrated 100 miles upriver. Twenty pound striped bass and Atlantic sturgeon ranged far from the ocean into New England’s second largest river.

Since 2013, the fish have had the renewed opportunity to retrace those routes imprinted in their DNA long ago. The removal of two dams and improved operations of a third has reconnected a significant portion of the Penobscot and those anadromous fish to their freshwater home. Hydropower generation, meanwhile, has not diminished at all.

The contemporary salmon run is considerably smaller than its historic counterpart. But after well over a century of manipulation, that’s to be expected. And even numbering around 1,000 fish in recent years, it still qualifies as the largest Atlantic salmon run remaining in the U.S. With the benefits of dam removals, their numbers are expected to grow. And as the fisheries rebound, other wildlife that feeds on migrating fish should also thrive.

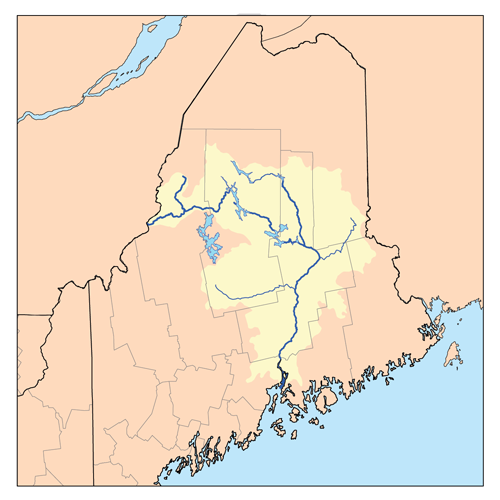

When the Penobscot River Restoration Project is complete, eleven species of native sea-run fish will have renewed access to nearly 1,000 miles of aquatic habitat that stretches across rolling hills, wooded swamps, and marshes from the shadows of Maine’s highest peak, Katahdin, to the Penobscot Bay near the town of Bucksport.

Long dormant cultures will see revivals as well, from the original Penobscot Indian Nation historically dependent upon the fish to Down East traditions of canoe building, fly-tying, and angling embraced by generations past. The reconnected river will introduce a new age of anglers, hunters, boaters, and tourists to the Penobscot already known for its wild brook trout and landlocked salmon fishing on the West Branch, with stout whitewater paddling above.

Did You know?

The Penobscot is New England’s second largest river, behind the Connecticut, and the largest river entirely within Maine.

The river is home to the largest Atlantic salmon run remaining in the U.S.

Up until 1992, it was tradition to send the first salmon caught each year to the President. President George H.W. Bush was the last to participate in the tradition, which was suspended due to declining wild Atlantic salmon populations.

In August 2012, the Penobscot Indian Nation sued the Maine attorney general and the heads of the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife and the Maine Warden Service over who has authority over the water of the Penobscot River surrounding the reservation.

What states does the river cross?

Maine

The Backstory

Archeological evidence of fish bones found in native settlements shows that the Penobscots fished for American shad as long as 8,000 years ago and for sturgeon 3,000 years ago. The subsistence fishing culture continued for generations, even as commercial fishing techniques evolved. But by the early 1900s, impacts of logging, dams, and industrial pollution had taken a terrible toll. By the 1950s, the shad, sturgeon, and Atlantic salmon runs once measuring in the tens of thousands essentially stopped.

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Northeast for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

As the region continued to develop, the river continued to suffer. Paper mills, untreated effluent, overfishing, clear-cut logging, and further dam building all contributed to its demise until federal regulators began to take notice. American Rivers named the Penobscot as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® every year from 1989 to 1996 because of existing or proposed dams.

The Future

Today, the Penobscot is a success story, thanks to advocacy by American Rivers, the Penobscot River Restoration Trust, the Penobscot Indian Nation, and others. The Lower Penobscot River Settlement Accord forged through collaborative efforts established an unprecedented plan to remove two dams and build fish bypass at others, effectively reconnecting the river with no net loss of hydroelectric power generation.

Removal of Great Works Dam, near the Penobscot Indian Nation and Old Town, Maine, began in June 2012, and removal of Veazie Dam began in 2013. And although the Penobscot remains far from dam-free, operators have been required to install improved fish passage systems at remaining dams. The last stage of the river restoration project took place at Howland Dam in 2015, just in time for the 2016 spawning runs.

The overall effort to open access to about 1,000 miles of habitat within the watershed is recognized as the most by any dam-removal project in history, making it one of America’s most significant river-restoration efforts. Reconnecting the Penobscot to the sea is restoring the health of the river and its fisheries. It is also revitalizing a key part of the Penobscot Indian Nation’s culture and creating new recreation and economic opportunities for all of the river’s communities.