Catawba River

once wild

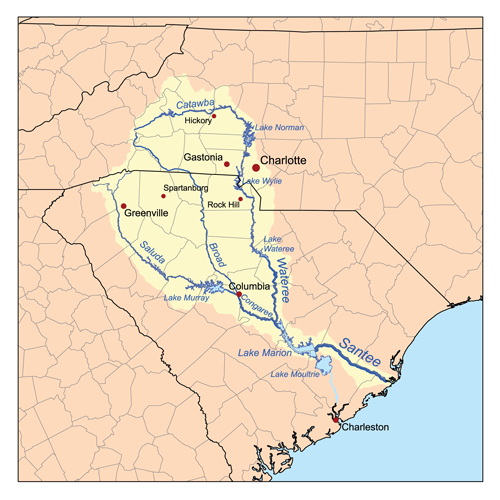

Spanning two states and more than 200 miles, the Catawba is more a linked series of reservoirs than a genuine river anymore.

This once-wild waterway named for the Catawba tribe of Indigenous People — “the people of the river” — rises in the Blue Ridge Mountains just east of Asheville, NC, and yields for no fewer than 11 impoundments on its way to and through South Carolina, where it eventually becomes known as the Wateree River before landing in Congaree National Park for its final 10 miles above Lake Marion.

Along the way, it weaves through some of the finest countrysides in the Carolinas, alternating between rural and urban landscapes, and passes by densely populated Charlotte, where it forms the 33,000-acre Lake Norman, a mecca of outdoor recreation.

The 30-mile stretch of the Catawba River between the Lake Wylie Hydro Station and the upper end of Fishing Creek Lake is now the longest portion of the Catawba River that remains undammed, forming a significant portion of the Wateree Blue Trail that winds 75 miles south to meet the Congaree River Blue Trail within the national park. The land bordering much of the Catawba-Wateree along the Blue Trail remains a wooded and natural floodplain forest, creating a haven for bald eagles, river otters, belted kingfishers, and wildlife of all sorts.

The Catawba River is also rich in history, providing for ancestors of the Catawba Indian Nation for some 12,000 years. European explorers and early American settlers eventually found their way to the valley and continue to flock to the region, all leaving their mark on the river. The basin is one of a precious few areas left in the southeast with significant populations of the rocky shoals spider lily (Hymenocallis coronaria), with notably the world’s largest population left at Landsford Canal State Park.

THE BACKSTORY

Beginning in 1904, a series of hydroelectric dams were constructed to harness the power of the river in an effort to foster growth in the region and meet increasing demands for energy. The hydro station forming Lake Wylie was the cornerstone of what is now Duke Energy, the largest electric power company in the U.S.

More than two million people now live in the Catawba-Wateree basin, and rapid growth is putting a strain on water resources. The lack of an overall plan for efficient water use is one of the reasons why American Rivers named the Catawba River one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® in 2008. In 2010, the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) named the Catawba-Wateree basin one of the top 10 most endangered places in the Southeast for the same reason. The Catawba Wateree Water Management Group has been focused on addressing some of the issues around water management that was highlighted by the droughts from 2007-2009 and the pressures of a growing population.

Did You know?

The Catawba River changes its name to the Wateree near the flooded confluence of Wateree Creek, reflecting the name of the native American tribes that inhabited the various regions of the river.

The Wateree River joins the Congaree River at Congaree National Park, forming the Santee River that eventually makes its way to the Atlantic Ocean.

The 30-mile section of the Catawba River downstream from Lake Wylie dam was designated a South Carolina State Scenic River in June 2008.

The section of the Catawba passing through Landsford Canal State Park is known for its large stand of rocky shoals spider lily, which has a spectacular bloom in mid-May to mid-June that may be viewed by boat or on foot.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

North Carolina, South Carolina

The river’s 11 hydroelectric dams combined with drought, climate change, and rampant development contribute to a variety of issues—including flow management, polluted runoff, and industrial waste—that continue to pose significant risk to the health of the river and the people that depend on it.

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Southeast for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

The tributary rivers that flow into the Catawba are littered with legacy small dams that powered the textile industry of the region but have now fallen into disrepair. Most of these dams have outlived their useful lives and now are just ecological and community liabilities. We have worked with some communities- like Hickory, NC on the Henry Fork- to remove some of these dams to restore the river and improve recreational and economic activities and there are many more such stories to come.

Coal ash, a byproduct of power generation, has historically threatened the river and local water supply with pollution. In 2020, the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality approved a suite of plans to close and excavate the coal ash move it to lined landfills or recycle it for beneficial use. This was a great victory for improving the health of the Catawba River.

The Future

It has been more than 100 years since the town of Great Falls, South Carolina has lived up to its name. But a landmark hydropower operating license has restored continuous flows to areas that have been bypassed since Duke’s Great Falls Hydro and reservoir were built in the early 1900s. In 2022, the new license will restore flows to whitewater rapids, create kayak and raft launches, and provide fishing areas with hopes of introducing ecotourism to the economically struggling town. Special whitewater releases are planned in the late spring and summer for visitors to enjoy.

Duke Energy’s relicensing process was the biggest hydroelectric dam relicensing in the nation, and the outcomes are leading to great improvements to the health of the river by dramatically altering reservoir operations, providing continuous river flows, enhancing water quality and reshaping how people use and value the river for the next half century. The new, 40 year license will improve the entire river system.

The FERC relicensing is reflective of modern conservation values and returns water to five sections of the Catawba-Wateree by establishing continuous flow requirements rather than daily averages, where the river could essentially be turned off and on in order to meet requirements. Some improvements are already being implemented, putting water back in the river channel where it historically has been redirected to generate electricity or cool power stations. That translates to improved recreational access as well as general river health for people, fish and wildlife, including endangered sturgeon and other fish species that make their home in the Catawba-Wateree river system.

Population growth and a changing climate are requiring new strategies for addressing water management in the basin. The most effective way of addressing them is through an integrated water management approach that protects critical areas of the watershed, invests in improved water delivery and treatment systems, and manages stormwater as a resource while restoring floodplains to better store excessive water filtering it and slowly releasing it back to the streams and rivers.

There are hundreds of dams in the watershed that are ripe for removal. We have been building a team of restoration specialist who can work with their communities to address these liability and support the removal of the unnecessary dams.