I’d been to the Gila before, many times before, but not like this. Never like this.

Santiago’s head cocked sideways, his little body limp, held up only by car-seat straps across each shoulder. Instead of mule panniers, food, and horse-tack in the bed of the truck, there are Legos on the floorboard, crumbles of colorful Play-doh, an empty Big-League-Chew bubble gum packet. Water bottles instead of whiskey.

Santiago sleeps as the first sight of the mountain is revealed, at last and for the first time in years, alive as can be, seen through my truck’s front windshield. Haven’t been this close – physically – to the Gila in sixteen years. But here I am again, my boy in tow.

I turn up the radio, and a part of me stiffens as we begin to ascend into the Black Range.

Santiago remains asleep as the truck swerves its way through all the turns, dozens of mountainous switchbacks. Llano turns to juniper turns to piñon turns to ponderosa. This two-lane highway, so familiar, yet I haven’t driven it in nearly twenty years. A playlist on the radio—Lucinda Williams, John Fogerty and Steve Earle, but also Las Hermanas Huertas, Paquita La Del Barrio, and Cornelio Reyna—familiar voices and songs, and the truck sways, and Santiago remains asleep in the back.

We cross into National Forest land, past the towns of San Lorenzo and Mimbres. Into Apache land, what the Warm-Spring Apache’s call NDE BEHNA, true name for the place we now call Gila.

At last, Santiago and I are here, and I imagine the water he’ll soon touch. Agua santa.

In May 2020, New Mexico Senators introduced the M.H. Dutch Salmon Greater Gila Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which would protect nearly 450 miles of the Gila and San Francisco Rivers and their tributaries under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the premiere federal river protection legislation in the United States.

But what does this mean to a six-year-old boy more concerned with Legos and MineCraft than any of the ‘boring’ news I read and watch?

The Senator’s email came through five days before Santiago and I set foot in the Gila, for the first time, together, mother and son.

Never really understanding much about legislation, and even less about congressional committees, I did know the power of law, so I read the Senator’s email carefully.

“My legislation to protect one of the nation’s most iconic and treasured rivers just passed out of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee with a bipartisan vote!…”

What did this email mean to me, a native Nuevo Mexicana? And what did this email mean to my six-year-old sleeping in the back seat, already three hours into our drive, up the valley into the Black Range, driving due east and closer to the great Gila?

“…The Gila and San Francisco Rivers are the heart of southwest New Mexico and are home to some of the most outstanding places in the entire West to go rafting, fishing, or camping…” continued the Senator’s email.

I thought of the time I first saw the Senator in-person, his tall stature, his chiseled face. I thought of what it was to have such power, such influence. A Senator, taut with insight and influence to propose legislation to protect a place and its resources. And what did it mean to protect anyway? Who defines ‘protection’, and what expandable definition can this concept have? Again, I thought of my own boy in the back seat of my truck. It was my duty now, to protect him. But how? And in both the immediate and deeper sense, what does it mean to protect?

Words from the email lingered; I too had worked in the Gila, much like Senator Heinrich, in the early days of my career. In what I’d gained from articles and interviews, he’d worked with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) on Mexican Wolf Recovery.

He was still doing great things for the Gila—he’d proposed legislation. He was making a difference. All I was doing was bringing my little boy to the Gila’s water,no power or political stature to my name. The email continued:

The Greater Gila watershed, including the San Francisco River and other main tributaries, comprises the largest remaining network of naturally flowing river segments in the Southwestern United States.

I thought of the many ríos that had shaped me, influenced me in more ways than words could describe. The Rio Grande of central New Mexico, its café-colored water flooding my Papa’s alfalfa fields each summer con benedición. The Rio Lucero of Taos, searching for Rio Grande cutthroat alongside Pueblo War-Chief staff and the tribal biologist of a federal agency; a wild July thunderstorm moved in, and we were taught humility in the deepest sense. The San Juan spanning both New Mexico and Utah’s corners; again, work had allowed me to know and learn about the ecology of a place most people only see in photographs, or now in Instagram posts.

Yes, rios had shaped me into the woman who now drove a truck heading deep into the Gila, a boy in tow.

“New Mexicans treasure the Gila because it provides unique and memorable outdoor experiences for families, spectacular scenery and wildlife habitat, and the foundation of a rural economy. Protecting the river will support enhanced water quality, local economic development, increased recreation opportunities, and healthy populations of fish and wildlife.”

And yes, I was a mother now, bringing my boy to a place important to me. It was this simple. This uncomplicated.

“It is time for us to provide the Gila with our nation’s highest form of protection and stewardship,” ended the Senator’s email. I thought about this last free-flowing river in our Southwest home. And I thought about how each of us who cared about this place, this río, had our part to play.

I couldn’t propose legislation, but I could sign petitions, I could remain aware and eager and spread the word about the Gila’s protection within my own familia. I could bring my boy to witness the Gila. It was this simple. This uncomplicated.

What Santiago didn’t realize is I forgot to pack a flashlight.

What the hell. How foolish was this? In all my hurried packing of food, sleep gear, water, emergency tools—in all my well-timed logistics, how the hell had I forgotten a flashlight?! I thought of the wild dark nights we’d be spending in the Gila, how this remote mountain-river-wilderness in southwestern New Mexico knew darkness. I’d forgotten to pack a flashlight.

And it was too late to turn back now. Already long past Hillsboro, past Iron Creek, Upper Gallinas, then Lower Gallinas. A winding Forest Service road. Already in the Mimbres Valley, I calculated the risk of this item I’d forgotten. My phone had a flashlight, and I had battery packs and a charger in my truck.

Santiago still asleep in the back. He didn’t care I’d forgotten a flashlight. At his age, carefree. I watched as the rio, adjacent to the road,ran wild—full, thick with a deep reddish-brown-color, clear remnants of an upper water-shed monsoon storm—evidence of rain. With evidence of rain in the river, I decided then and there we’d drive on. It was too late to turn back now.

The Gila River, a 649-mile-long tributary of the Colorado River flowing through New Mexico and Arizona, is also one of the longest rivers in the west. And I sit and wonder HOW to introduce my boy to this place.

The river is the heart, the lifeblood of the Gila Wilderness, National Forest, and surrounding landscape and ecosystem.

The Wild & Scenic legislation would protect 450 miles of river, keeping it free flowing in the face of development or other ‘use.’

But the question remains, HOW to introduce my boy to this place?

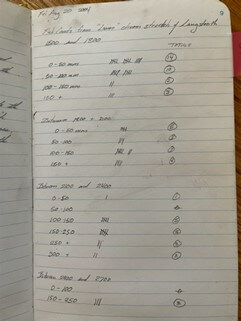

My OLD field notes as a fish biologist in the Gila read like this entry from 2005: Something tells you to listen. Something tells you to listen carefully. Thunder in the canyon. Rain speaking. Water speaking. And a cold August dampness in the air forming words on your skin like an orange tattoo.

It is now the year 2022—17 years later. I am no longer a fish biologist working in the Gila. I am a visitor again, as I always was. A visitor.

The yellow Rite-in-the-Rain hardcover book containing all my old Gila notes is only half-full of the notes I used to take while working deep within the Gila Wilderness, what now feels so long ago. The first date reads Friday, August 20th, 2004, and the last, March 28th, 2008. Four years spanned my formal working days in the Gila Wilderness and River, a wannabe biologist among the headwaters, los rítos. I was a young woman, struggling to find my way into a career, but more honestly, through life, searching for a space of identity and understanding among men and wilderness.

I was introduced to the Gila long before I became a mother to a son. Even as a native Nuevo Mexicana, a brown girl raised in the farm fields of the middle Rio Grande valley, I did not know the Gila in my childhood days. It was a place I’d only heard of.

With today’s current climate conditions—megadrought looming in the American West—I search back through memory and time, trying to define for myself, as much as for my young son, why exactly the Gila has become so important to me.

The yellow Rite-in-the-Rain hardcover book containing all my old Gila notes is only half full. And as I drove INTO the Gila again for the first time in 17 years, I thought about all I’d written back then. More importantly, I thought of the empty pages the book still contained, what more I had to discover, what more left to learn.

JOURNAL ENTRY, 2005. In the mountains, thunder directs your thoughts. And bees gather around objects—your backpack, the bucket, the yellow book, wet shoes. Everything is the way the mountain wants it. In the rain, you’ve got to keep your head down, it teaches you humility. Sometimes the Gila is about slow and deliberate motion, or that thick smell of whiskey in a tin cup. Sometimes it’s about the way paper warps in the rain… There is yellow in only the smallest places of the mountain. In the flowers, on the bees, on the flowers. Most of this mountain is a thousand shade of browns and greens, and the combination of all this color is like waiting for the sound of water to break into you.

Your hands smell like tree sap and purple flowers. The rain has stopped, for now, and you wait for Richard to arrive from the upstream duty post. You listen for the sounds of his arrival – the splashing of water and gravel and rocks, the occasional breaking of branches, his movement downstream. There is stillness again, under a grey sky of occasional thunder, and we work through it all, a color green.

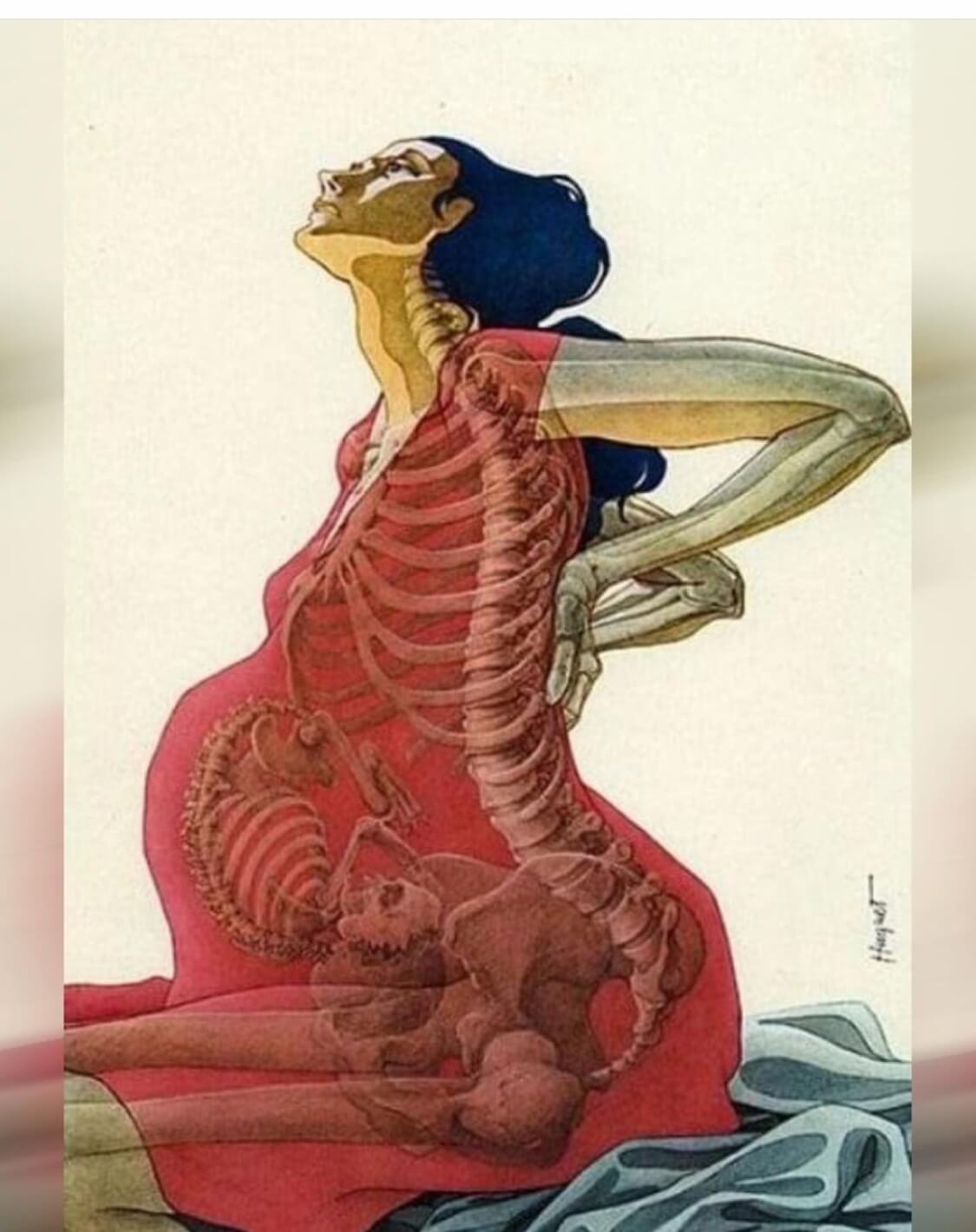

In her essay, “The Vessel & the Water,” Kailea Frederick describes, “In those nine full months, my womb was neither fully mine nor his, our bodies blurred so completely that even when he finally came through and out of me, our delineation of self remained soft and unfocused, a horizon line of hazy blue touching the forever expanse of the sky, indistinct in color or shape. I was the vessel that held the waters in which he grew” (https://humansandnature.org/the-vessel-and-the-water/).

My boy was born on a Friday, 2:51 am. I labored for 17 hours until at last the nurses gave the C-section order, and they cut him out of me.

“I was the vessel that held the waters in which he grew,” states Kailea Frederick in her gorgeous description.

Looking through my notebooks—the kind I’ve kept for years—of daily notes and ritos of time and place, I try and find the earliest instances, phrases, documentation of what it was like for baby and me starting off together as one. There are writings, mentions during pregnancy, but not after. Nothing in the days, hours, months, after his actual birth. They cut him out of me. This time frame, these days AFTER the baby’s birth—all my writing entries fall short.

I wrote nothing about the baby. I wrote about other things, many other things, but NOT about the baby.

This biologist and writer who was TRAINED and DISCIPLINED in writing and note-taking, could suddenly not write. I did not write about the baby, or even about me as mother.

Was I afraid to write the truth? Or at the time, did I simply not know the truth?

The closest I find to mention of baby or motherhood, or ANYTHING tangible, isn’t until one year and one month later.

Something in me was hesitant, afraid to write, until, at last, it wasn’t.

JOURNAL ENTRY, OCT 25th, 2016 (one year AFTER my baby’s birth). Eating fruit with a fork reminds me it is Tuesday, and last night Santiago woke at 01:30 AM, crying, but was calm and quiet as soon as I picked him up. He is comforted just by my touch. I hold him close to me, and the room is completely dark. He is leaning into me. I am holding him close and tight to my chest. I am just beginning to understand what it is to be a mother. At last, it feels like love to hold him.

My boy was born on a Friday, 2:51 am.

“I was the vessel that held the waters in which he grew.…” And yet it was a struggle, all the early days, a deep struggle, a wilderness even now I cannot name, cannot admit to. Where does one hide from the sin of a mother who cannot, does not, love in those early days? Even the expanse of the great Gila wilderness cannot contain such darkness. Even the free-flowing Gila River cannot wash away such disdain.

JOURNAL ENTRY, SEPTEMBER 2005. Soaking rain during the ride that took us six and a half hrs. Slept warm with the saddle blankets beneath a grey tarp in the tent that was set up between Jerry and Johnny. As for now, I am alone with this mountain, ‘watching’ the two lowest buckets on Langstroth creek wondering if I will make it out of here unharmed. In many ways you are useless among all of this. Out here, if you get hurt, you’re on your own.

The sun keeps coming in and out, in and out…there is thunder. Orange flagging marks the lowest bucket of chemical treatment as we work. Thunder. And it is only fourteen minutes past noon. Yesterday at this time we were in the saddle, taking the trail that eventually leads into and out of Hell’s Hole.

The presence of thunder is never mistaken for anything other than thunder. And yet here in the mountain it is common. They say these are the days of the monsoon. It is so different to experience all this wetness and rain than to merely hear news of it through a coworker. So much more terrifying to experience. It forces you into being right now, right now, right now. And never any time before or after or otherwise. The way thunder-rain comes into a canyon is fast.

Thunder-rain thru the mountains. Dressed in a color we had never seen before. Speaking something blue. And it rumbles the silence right out of the trees while the wildflowers are busy at conversation.

When working in the Gila, it was always about the fish. But also, it was never about the fish. Gila trout, a federally listed species, was reclassified from endangered, down to threatened in 2006.

Gila trout: one of the rarest trout species in the United States.

Native to mountain streams of the Gila, their populations HAVE seen an increase in total WILD populations through recovery efforts over the years.

In 1992, their numbers were estimated to be less than 10,000 fish older than 1 year.

In 2001, the population in New Mexico was estimated to be over 37,000.

Intensive stream renovation and transplantation efforts have worked.

But what does it mean to ‘recover’ a species? What does it mean to protect a place? What does place TEACH us? How do species and ecologies of PLACE inform our own human lives, and why does any of it matter?

I used to work on fish-recovery efforts: treating upper watershed creeks with chemicals, eliminating all fish existing within very specific stretches to ‘make room’ for this rare and threatened trout. I used to pack in to the Gila Wilderness with large crews, mostly men, working for days that turned into weeks.

Now I am mother to a young boy. I no longer work as a biologist or field tech.

But even now, I still ask, often and always, what does it mean to ‘recover’ a species? What does it mean to protect a place, how do places become IMPORTANT to us?

I reach out to Chad Baulmer, the USFWS biologist currently assigned to Gila trout public inquiries. I reach out via email, and he replies, tables and numbers attached. But what I really want to ask him is, “Did your heart skip a beat when you first held a Gila Trout? Do you still remember the fire-orange along its lateral line and fins? What excitement still lives within you since the first time you witnessed this species in the wild, this endemic fish, this species worth saving?

But I don’t write that in the email. Instead, another ríto wells up inside me, another question, another source. It begins slowly, agua moving thru soil and boulders of a high-mountain forest. Headwaters of my alma—the smallest ríto already inching its way into the expansive eternity of an ocean source not yet realized. “Thank you for the information,” states my emailed reply to Chad the biologist, and I sign the end of the email with my three initials—LTT—the way the field fish biologists taught me so long ago, always 3 initials instead of just two. Three initials in honor of my old field days of taking notes in the Gila. Will Chad the biologist notice this end-of-email signatory? Will he sense I TOO once worked on recovery efforts? No, he doesn’t know me. And I smile at my own anonymity.

For a good six months or more, Santiago’s favorite snack has remained apple slices and Funyuns. Although his likes and dislikes change much like his padrino, my brother, THIS snack of choice has remained. Yes, apples and Funyuns. Yes, those ridiculous salty corn rings sold in a bright yellow bag, marketed to look like onion rings, but really the only ‘onion’ ingredient is ‘onion powder’ listed as one of the very last ingredients. My boy loves apple slices and Funyuns, and I won’t try to describe to you the wicked-strange breath out of his little laugh after he eats his snack.

“Mama, I LUHHHOVE YOU,” he pushes out hot intentional breath trying to reach me as he jokes, knowing this annoys me as much as it makes me laugh.

“Uhhhgg, go brush your teeth!” I yell back as he continues to breathe on me, laughing, trying to climb up on me, pulling on my hips while I push him back, my palm on his forehead. Both of us laughing, Funyun-crumb residue on his shirt chest and belly, his fingers sticky from the apples too.

“No, for reals, go brush your teeth,” I finally insist, and off he goes to the bathroom, stepping up on a little stool to reach the sink. My boy brushes his teeth, and I stand outside against the door, a space where he can’t see me, and just listen to him hum a little song while he brushes his teeth. Looking down at my own shirt, there’s Funyun powder residue all over me now, but I leave it there, and keep listening until he’s done, and in a hurried rush he slams the wood cabinet drawer shut with a loud thud as he puts his wet toothbrush away.

River and boy, river and boy—both teach me not only about wildness, but about what it is, not to be a mother, but to become a mother.

Just as rivers become rivers from headwaters, so have I struggled to become a mother. Gentle. Peaceful. Teacher. Loving.

Water connects us in obvious ways. But it’s the smaller ways, the intimate ways that take us by surprise, that hold a different color, that remain.

Thus, in many ways, mine is a story about water—agua. Es una estoria de cambio—change—and of how our relationship to a place—an element, like water, like mountain, like wilderness—can change over time.

I lean into the fragments, the many tributaries of my querencia.

Querencia: a deep love of place, or belonging to a place. Fragmented tributaries of experience, stories, and time spent IN and AT the Gila’s water. Creeks, streams, and headwaters converging and leading always into the deeper understanding.

The word querencia is a popular term in the Spanish-speaking world that is used to express a deeply rooted love of place or people. And though it’s a Spanish word, the idea of Querencia is truly universal, its translation endless and ever widening.

Querencia: the place of your deepest identity, your deepest longing; a place in which we know exactly who we are; the place from which we speak our deepest beliefs.

Writers such as J. Drew Lanham might refer to this concept as “home-place.” Similarly, Robin Wall Kimmerer might call it “kinship.” But here in Nuevo Mexico, some of us call it “querencia,” that which anchors us to the land. A deeply rooted knowledge of place.

It is strange returning this way, returning to the Gila not as a fish biologist, but as a mother. My title, my qualifications are gone. I still have the university degree and an old resumé, but what does that matter when returning to a place you knew and observed from a worker’s perspective?

I think of the men who taught me about and in this place. Jim, Johnny, Dave, Vern. Where are they now? I think of the horses and mules, those who had nicknames, and those who didn’t. Where are they now? Time has passed. Seasons and years.

“Mama, can you take off this Lego for me?” asks Santiago, holding up a little tower he’s constructed. “This yellow one is stuck to the black one, and I want to change it but can’t get it off.” He holds up his toy creation as I try to get our gear out of the truck and set up for our stay in the Gila.

His little toy tower, and I am focused on logistics. I am too caught up in the past to notice the urgency right in front of me. The present. The now.

That night my boy and I sleep under a Gila sky, the cosmos laid out in deep black, a scattering of constellations. “What’s that one?” asks Santiago. “And what about that one?” playfully. “No se, mi hito, I only know the Seven Sisters.” There is so much I don’t know, and yet he’s aways asking me for the answers.

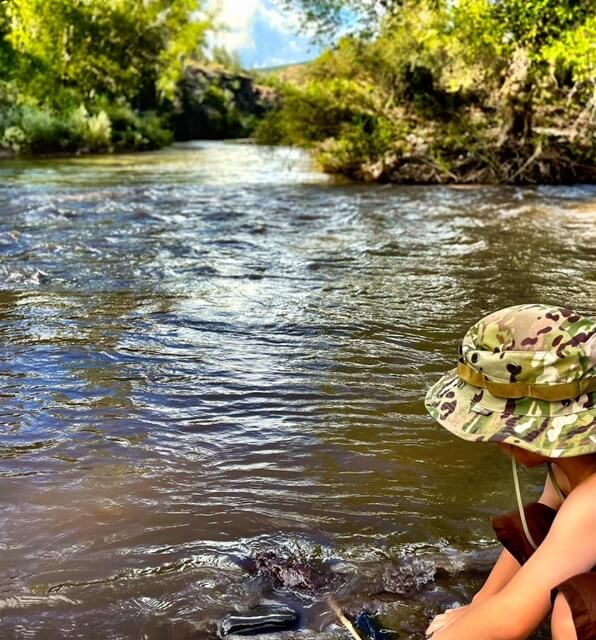

The next day, we find a ríto named Sapello. We look for fish, turn over rocks, eat apples and a bag of Cheetos at the edge of where the stream runs endlessly. I sit there, considering the Gila as STILL the last free-flowing river in NM, thanks to the EFFORTS of so many intent on protecting its wild and native flow.

Willow and olive trees provide shade as Santiago plays—splashing his feet in the water, throwing sticks, asking, “Is that a fish, Mama, is that a fish?”

“No loco, that’s just algae, see?” And we proceed to pull some of the silky green off rocks, exposing it above water to get a better look.

We had no real agenda that afternoon, I realized later, and Santiago never asked for one. We were just at the creek. Looking for fish? Climbing rocks? In its very essence, we were just at the creek.

What sort of privilege is this? To have time and resources to just play in the water. Previously, all my time in the Gila was dedicated to work. Labor. Pack this, plan that, pack in on mules, take notes on water quality, habitat elements like substrate and bank-width, then pack it all out. This is how it used to be. This is who I was. Trabajo. Work.

What Santiago was suddenly offering me was the notion of playfulness, enjoyment. I’d never had that in this place. Even as a child, we were not a ‘family’ of ‘recreators.’ Papa worked. Mama worked. We didn’t take camping trips, or boat at the lake, or fish in the streams. Papa worked. Mama worked. Then I worked. Then when I was introduced to the Gila, it was with men and work and whiskey. But here I was with my boy, and his playfulness surprised me.

We’re still exploring, Santiago still playing, and I begin to sense and see a monsoon storm moving in.

“Hey, let’s go,” I say to Santiago. Downstream, thunder rumbles, the sound getting closer than just a few minutes ago. I hustle, making sure we’ve got everything, preparing to leave.

I start scrambling, moving faster to get our things gathered up, backpacks, rain jackets, water bottles, snacks. Santiago is still playing. “Hey, for reals, let’s go,” I say to him, my tone dropping. “Ok, ok,” he responds. He’s still at the edge of the water. “Let’s go, let’s go,” urges my voice out loud again. Still, I’m scrambling, watching the sky, the movement of storm, but also making sure I’ve picked up everything.

It’s then I hear: from the water’s edge, Santiago says to me, “Mama, bless…” I turn to see him standing in the water, at its edge, calling me over.

I go to him and almost instinctively, I crouch down. We are both at the water. Mother and son. Presence of incoming rain tells me we should hurry. But Santiago’s sudden calmness tells me not to rush. “I gotta bless you, Mama,” and he puts his hand in the stream, and with a scooped hand, he pours water on my head.

Then he does it again, this time smushing his hand in my hair. More water, messing up my hair with his motions. He scoops water from the creek. Again. Again. He’s getting my head all wet.

A blessing.

I think then of all the times I’VE blessed my boy, a tradition given to me by my own mother and father. When we were children, Mama and Papa would always bless my brother and me with a holy sign, a physical gesture. With the right hand, they’d touch our forehead, chest, shoulders, speaking aloud, “padre, hijo, spiritu santo…”

A blessing.

They’d bless us when we’d leave the house. They’d bless us if we’d go with our primos or to Nana’s house. They’d bless us before going to school. They blessed me when I left to the Marine Corps. This blessing also extended to include water—especially on June 24th, dia de San Juan—when Papa would playfully bless us with water, spraying us kids with the hose, or splashing water on our faces first thing in the morning.

Mama and Papa were always blessing me. Even today, they still do. And in turn, I’ve extended this tradition to my own boy.

For the last six years, I’d blessed Santiago too. But in my own way, I’d also extended this tradition, often blessing him with water. When walking along the Rio Grande near the house, I’d say, “Bird, come here. Let me bless you.” I’d touch my fingers to water, then to his forehead.

When playing or working near the acequias at home, I’d dip a finger in the water and bless him, finger to water, then to his forehead.

His first time at the San Juan near Pagosa Springs, I led him to the stream edge, scooped water from a riffle, and wet his head. A blessing.

This is what my familia did. It is what I’d been taught. It was the action I took.

But what I didn’t realize is that it had translated. THIS small action had translated. Santiago had been paying attention, and now suddenly, completely unprompted, he was asking to bless me. He was asking to bless me with Gila water, and all I was concerned about was outrunning the rain and ensuring we’d picked up all our Cheetos bags.

Santiago scooped up more water from the creek. He poured water on my head, messed up my hair. A blessing from the ríto. My boy, suddenly blessing me.

As a New Mexico native, born a daughter to this American Southwest, my desert life has always been a story about water—agua.

I’d followed through television and reported news stories, the battles and controversies to dam the Gila River. I’d supported federal legislation proposals to protect certain portions of the river. I’d tracked the news stories as fires and then floods moved across the Gila landscape.

But among and within all of it—current, historical, political, or otherwise—it is our RELATIONSHIP to place that inspires action, cambio, querencia.

My head now dripping with water, I look up. Santiago is smiling. He’s smiling and almost laughing. It isn’t him being travieso (ornery or badly behaved), it’s him being playful. And I let him.

“One more time,” I ask him, and immediately he reaches for more water, drips it on my head.

His playfulness isthe prayer offered to the Gila. His playfulness is a re-envisioning of my own relationship to this place, mi querencia. I am not here in the Gila as a girl who works, but as a woman and mother now.

Similarly, my deep hope for Santiago is that this playfulness will also be the origin of this as his own querencia. Maybe. Si Dios quiere.

Thunder rumbles in the distance, not low and deep as before. “Eeee, let’s go,” I say to Santiago. “Ok!” he replies and jumps easily and willfully up and out of the stream, his botas sopping wet. He could care less and starts running up the trail. I scoop up bags, wipe water from my face, all of it still from Santiago’s playful blessing.

Then rain begins to fall. We rush back up the trail, upstream toward the truck, Legos still scattered on the floorboard, apple juice instead of whiskey.

THE END.

Leeanna T. Torres is a native daughter of the American Southwest, a Nuevomexicana who has worked as an environmental professional throughout the West since 2001. Her essays have appeared in various print & online publications (Blue Mesa Review, High Country news, High Desert Journal), as well as anthologies. She is also currently at work on a creative-non-fiction book manuscript centered-on landscape, culture & querencia. Leeanna received the 2021 Southwest Emerging Artist Scholarship from American Rivers to participate in a FreeFlow Institute writing workshop with William DeBuys on the Green River, which led to this essay.

Thank you to Senator Martin Heinrich, Senator Ben Ray Lujan, Representative Melanie Stansbury, and Representative Teresa Leger-Fernandez for working with their leadership to try to get the M.H. Dutch Salmon Greater Gila Wild and Scenic Rivers Act passed before the end of 2022!

Progress is the reason American Rivers named the Neuse River its 2022 River of the Year — progress since the passage of the Clean Water Act 50 years ago and progress that is yet to come. None of it could be accomplished without the dedication and determination of the communities along the Neuse’s banks. Leading the movement to protect the Neuse and its sister river, the Tar-Pamlico, is nonprofit Sound Rivers, with a mission to guard the health of these two critical watersheds.

Sound Rivers’ Neuse and Pamlico-Tar Riverkeepers work with concerned citizens and state and federal agencies to monitor, protect and restore the two river basins. Founded in 2015 with the merger of two of North Carolina’s oldest grassroots conservation organizations, Sound Rivers combined the deep history of advocacy of the Neuse River Foundation, established in 1980, with the Pamlico-Tar River Foundation, established in 1981, to form an environmental powerhouse. Today, Sound Rivers celebrates more than 40 years of advocacy and action on behalf of the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico rivers and the communities that rely on them.

This is no small job. The two river basins cover nearly one-quarter of North Carolina and provide drinking water to most of their residents. Together, they contain unique habitats including bald cypress swamp, mixed oak, and pine forest, and salty estuary, and are home to a huge array of plant and animal species, including the threatened Neuse waterdog, the Tar River spiny mussel, and the Carolina Madtom — each of which can only be found in the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico watersheds. The rivers are the lifeblood of outdoor recreation, providing world-class opportunities for fishing, kayaking, birdwatching and simply soaking in the natural beauty of North Carolina’s Piedmont and Coastal Plain. To many, the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico rivers are what make southeastern North Carolina home.

Sound River’s long history of work protecting the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico watersheds is a testament to its grit as an organization. Over the years, they have faced off against powerful opponents and netted some unlikely victories in defense of water quality and river-reliant communities. In its 40-year history, Sound Rivers has gone head-to-head with big mining proposals to dump toxins in the water, shined a light on waste from concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) polluting waterways, advocated to stop the leveling of riverside forests, and worked tirelessly to reduce pollution from wastewater treatment plants and big industry.

Sound Rivers’ core belief is that all people should have access to and enjoyment of natural resources, as well as a powerful voice in decisions that may affect their environment and health. While we have come a long way since the early days of dumping toxins directly into the Neuse, many communities along the river still bear the burdens of pollution, outdated infrastructure, and flooding. For Sound Rivers, challenging environmental injustice is a critical part of watershed advocacy — addressing these issues in the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico watersheds must start in their most vulnerable communities. Working hand-in-hand with community members most impacted by pollution, Sound Rivers aims to kick polluters out of underserved communities and ensure watershed benefits can be shared by everyone.

Sound Rivers’ work is not limited to the reactive — the organization also does plenty of proactive work. Its Campus Stormwater Program partners with local schools and universities to assess campuses and implement green stormwater infrastructure to prevent polluted runoff from pouring off buildings and parking lots, straight into waterways. Sound Rivers also seeks grants to fund and create watershed restoration plans with local municipalities and install trash-collecting devices to passively collect trash flowing downstream in critical urban waterways.

Encouraging public enjoyment of the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico waterways is another part of this work: Sound Rivers participates in Swim Guide, an international program, sampling popular recreational spots and publishing data-driven, weekly swim advisories each summer. In all, Sound Rivers is a champion for the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico watersheds, a watchdog dedicated to calling out polluters, and a caretaker working tirelessly in loving service to its charges.

While Sound Rivers recently marked its 40th anniversary, the story of the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico rivers is still being written. In the face of increasing threats from a changing climate, Sound Rivers continues to work hand-in-hand with communities to improve water quality and safeguard these rivers from the challenges ahead. Much has been accomplished over the years, but there is much more work to be done. Looking ahead, Sound Rivers intends to write 40 more years of progress into the next chapter of the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico rivers — chapters of hope for generations to come. Achieving its goals requires collective effort. All are welcome to join the fight for clean water.

For more information, visit soundrivers.org.

There’s a stillness that comes with rivers in winter months. Many rivers freeze over in the north, while some rivers in the south have never seen ice. But they all know winter. The sound of water running over rocks is almost more palpable as a brisk wind flows over the river and hits your cheeks. As fish retreat further underwater to conserve their warmth, as birds have flown south to follow warmer temperatures, as friends once sunbathing on riverbanks now gather at their houses around a fire, the feeling a winter river brings is noticeably different.

For me, rivers in the winter make me more reflective. While the sun rises later and sets earlier, the hours in which you can spend at the river become fewer. You learn to cherish the times you can make it down to the banks to catch the small moments that make each river so unique and special. My favorite river, The James River, in Richmond, Virginia, has a different personality in the winter. Rafters and kayakers don’t spend as much time throwing tricks in the rapids as the bundled layers under dry suits make it harder to manipulate their boats. Students from nearby universities aren’t splayed out on the rocks blasting their favorite tunes. Not as many dogs are swimming around – but there are still a select few that can’t resist a nice stick tossed in the water.

It brings me such joy when I see all those wonderful things happening in the summer, but in the winter it’s quieter. You can hear each small ripple of moving water. You can see the large nests beautifully constructed by Bald Eagles and Osprey in trees no longer full of vegetation. You experience the bare bones of the river, which reminds me that the river is not there to just support human life, it supports an entire ecosystem of plants and wildlife year-round.

We asked some of our staff members to reflect on their favorite river in the winter. What makes their river special? What lessons do winter rivers hold? What is their relationship like with rivers in this colder season? Is there a specific stream or river they like to visit this time of year? We received some beautifully written responses.

Please share with us your favorite winter river and what makes it so special!

“My favorite part of winter with our local river, Russian River, is the way the fog rolls in and blankets the river and surrounding forest creating a cottony, mysterious, yet calming place…The river always flows, the ocean is always there, waiting for it.”

“Nine Mile Run in Frick Park, which I enjoy for “snow treks” because there are great walking trails along the creek and it is less than a mile from my house… “Snow treks” are soul-restoring ventures that I really look forward to.”

“I like to walk the higher-elevation sections of the [Nooksack] river in the winter as the snow-covered banks do little to hide the tracks of river visitors who I don’t get to see every day (mink, otter, deer, bear, coyote). It reminds me of how important this river is to things/beings that I might not get to see.”

“Sandy Creek is a small stream in the headwaters of the Youghiogheny River that flows through the woods in the backyard of our family cabin. In the winter, when all the undergrowth except the rhododendrons has died back and snow covers the ground, it is a magical time to follow the stream and try to find where it starts.”

“My favorite trails took us along the Saco River…the ice flows stacked chunks of ice on one another making for awesome shapes with blue reflecting on the underside. I loved those days when even the rivers seem to quiet for a bit hidden under the ice.”

“My favorite winter river is a small tributary of French Creek, outside of Saegertown, PA, just south of Lake Erie…The silence in the woods was magical, punctured only by the sound of the wind and the stream running, still alive, under the snow and ice.”

P.S. As always, please be sure to tag us (@AmericanRivers) in your outdoor adventures along with True North (@TrueNorthEnergy). True North shares American Rivers’ goal of protecting the outdoor spaces we love to play in, as well as protecting what goes into your body with their energized Sparkling Water with an organic plant-based energy blend.

After more than 100 years of being dammed, the lower Klamath River will flow free once again.

To be able to make that statement, it has taken decades of advocacy by Tribes who depend on a living Klamath River for their cultural identity and for their food security. It has also taken years of effort by the Tribes, the states of California and Oregon, the dams’ owner, federal agencies, and several nonprofits, including American Rivers, to navigate the lengthy planning, fundraising, regulatory and project design processes. But finally on November 17, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approved the hydropower License Surrender to remove four dams from the Klamath River. The License Surrender follows from earlier this year, when FERC issued a Final Environmental Impact Statement recommending that the dams be removed due to their cultural and environmental impacts. There are more steps that need to be taken, including additional regulatory steps, before deconstruction can begin in 2023, but a project that has been decades of struggle and seemed to be falling apart as recently as two years ago, now feels inevitable.

The Klamath River basin is home to the Karuk, Yurok, Hoopa, and other Tribes. Salmon are both a food source and a focal point for their cultural identity. The Klamath was once a highly productive salmon river with one million fish returning to the river each year. Largely because of the four dams, there are no longer enough fish for the Tribes to have Klamath salmon as a primary food source.

In 1918, the Copco 1 Dam was completed, cutting Klamath salmon off from the upper part of the basin. Over the next 44 years, three more dams were built (Iron Gate, Copco 2, and J.C. Boyle dams) on the river in California and Oregon, effectively closing off 400 miles of habitat to salmon and steelhead, ultimately resulting in dramatic fish population declines.

Perhaps even more devastating to life in the river, the dams’ reservoirs became breeding grounds for cyanobacteria. It is a substance that looks like a blue-green algae and is toxic to aquatic life, to humans, to livestock, and to pets. The Karuk tribe measured a Klamath toxicity content that exceeded World Health Organization guidelines by almost 4,000 times. There are warning signs near the water. When you look at the reservoirs, they look wrong, a color that makes you instantly cringe when you see it. The phosphorescent film also traps heat and depletes the oxygen content in the water. As a result, 90% of the small number of salmon that return to the river become seriously ill. Between habitat fragmentation and terrible water quality, the fish do not stand much of a chance with the dams in place.

Removing the dams will end these problems. The fish will be able to return to habitat they have not seen for a century. Cyanobacteria will be no longer be a problem – it does not persist in flowing water. The beautiful Klamath River will be better able to sustain life.

Now that the Klamath project is closer to the end than it is to the beginning, I wanted to share a few reflections on things I have learned through the project and how the project resonates nationally:

1. We need to do better for tribes and justice and food sovereignty.

The Klamath story is one that is too common for Indigenous people. While the outcome on the Klamath will be positive, the path to get there has been a struggle. In 1864, the Klamath Tribes negotiated a treaty with the United States that affirmed their sovereignty and included rights to fish for salmon. It was signed and ratified by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1870. Over the next century, U.S. companies built dams on the Klamath River that wiped out two species of salmon and brought the populations of the remaining salmon to 5% of what they were. The tribes had the right to fish, but the fish were nearly gone. In 2000, when the dam owner, PacifiCorp, did not include provisions for fish passage in their initial bid to relicense the dams, tribal members went all the way to Scotland to protest to PacifiCorp’s parent company. Later, when Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway acquired PacifiCorp, tribal members went to Nebraska multiple times to protest at the company’s annual meetings. A real turning point in the project happened in 2020 when Berkshire Hathaway executives accepted the tribes’ offer to visit the dams and meet with tribal members on the river. The tribes’ advocacy made these dam removals possible, but it should not have taken this much for the tribes to retain a cultural focus that they have had since time immemorial – that the Klamath River is free to sustain life.

2. Dam removal makes economic sense.

In ultimately deciding to decommission the dams, PacifiCorp made a sound economic decision. An early draft FERC report estimated that the dams would lose $20 million per year including expenses to operate the dams and expenses to address the dams’ water quality impacts. The California and Oregon Public Utility Commissions confirmed this, determining that dam removal would result in cheaper energy costs for their ratepayers than relicensing the dams, so much so that ratepayers are contributing hundreds of millions of dollars to remove the dams. Paying to eliminate underperforming infrastructure is a sound fiscal decision. What’s more, the power from the dams can be replaced with clean renewables and efficiency, without contributing to climate change.

3. We need to make it easier to decommission hydropower dams.

PacifiCorp originally agreed in principle to remove the dams in 2010 as part of the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement (KHSA). In 2016 the KHSA was amended with a more defined plan to transfer the dams for removal to a new nonprofit entity, the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC). But then, in 2020, FERC denied the initial license transfer from PacifiCorp to the KRRC. The states of Oregon and California stepped in and agreed to become co-licensees, an unprecedented step that rescued the project. With the new license transfer structure in place, FERC was able to issue the Final License Surrender Order. It took 12 years after PacifiCorp agreed to remove the dams in principle, and 22 years after they first started the relicensing process, to finally determine the fate of the hydropower license and the dams. As is usually the case with dam removals, the dams will come down faster than the process to get to removal. American Rivers will continue to advocate for improvements in the processes that allow dam owners who consent to removal to remove their dams.

4. The States of California and Oregon continue to prioritize river restoration.

Through various programs, both California and Oregon provide millions of dollars each year for river and wetland restoration projects. Along with rescuing the Klamath project during the license transfer process, both states have supported the Klamath Dam removals from the beginning. Their restoration ethic should serve as models for states throughout the country.

5. The approach to develop a new nonprofit to implement a complex project has worked (again).

The Klamath River Renewal Corporation was modeled after the Penobscot River Restoration Trust, a similar structure developed to remove hydropower dams in Maine. In both cases, very complex projects were well managed by skilled staff hired for the purpose. The staff at the KRRC and their consultants (Resource Environmental Solutions (RES) and Kiewit Infrastructure West) are making the nuts and bolts of the Klamath project possible. There is no better example of that than the Final Environmental Impact Statement issued by FERC. It includes hundreds of pages of challenging issues, from cultural resources to sediment management to engineering design to public safety issues, that all need to be managed in a complex project like this. Every one of them has a clear statement of how they will be managed, demonstrating the level of thought and analysis and engineering that the KRRC has put into the project. I have seen reports on similar projects stating the impossibility of managing this much complexity. KRRC is making it all possible and clarifying that while there are many issues , they can all be reasonably managed.

This effort on the Klamath River will make history: never before have four dams of this magnitude been removed at once. The Klamath dams are large structures, ranging in height from 33 feet to 172 feet. Every successfully completed project makes the next project easier. I hope that the Klamath projects will serve as models to complete more large-scale river restoration projects throughout the country.

The Klamath dam removals will begin in 2023 and will be completed in 2024.

Sometimes the threads through our project work loop around in seemingly random yet occasionally beneficial or surprising ways.

The story of the Van Reed Paper Mill Dam removal project began more than 10 years and two staff coordinators ago on Cacoosing Creek in Reading, Pennsylvania. But in some ways, it began in the 1800s when the mill was in full operation.

The thing about dam removal projects is that you don’t always know what the path will look like between the start and the end. Getting from here to there, that path can be interesting, frustrating, exciting, challenging, enlightening, and so many other things that make doing this work so fulfilling. The journey is not wasted (although you may wish at times that you did not have to take a certain meander).

So, the journey.

There it sat in 2019. Paper Mill Dam. A relic of a former time. At least seven years of project history behind it already (we’ll get to some of that). The permit package had been submitted, but there were UNANSWERED QUESTIONS on the design. No one wants to deal with those. So procrastination sets in. And so it was that I picked up this project. Just get it done. Easier said than… well, you know.

I get the answers. We get the permits. Someone else already did the fundraising. So, we just pull the sucker out, right? Wrong. There I was, rolling along— hired a construction contractor (Flyway Excavating) and construction oversight engineer (Kleinschmidt). I have a baby (awwww). I come back from maternity leave ready to hit the ground running. We all go to the pre-construction meeting to walk through the plan before the actual work begins and representatives from the neighboring homeowners association (HOA) appear on the scene. We had been planning to dispose of the dam material in an existing open concrete basin on the opposite side of the river from the mill. The dam owner, Rob Marella, had an agreement with a builder to be able to use that bank along the river. The HOA did not want to adhere to that agreement. You see, these are the crazy things that pop up when projects take so many years to do.

I’ll back up a little further in the story to explain why it took so long to get to this point. It wasn’t just the UNANSWERED QUESTIONS. You see, when they built the neighborhood across the river, the dam owner allowed them to install a natural gas line upstream in exchange for his use of the opposing river bank downstream. When conversations started about removing the dam, it took quite a lot of back and forth negotiation (i.e., years) with the natural gas company to come to an agreement on the design approach in the upper end of the impoundment where the gas line was located. We thought that was all settled, then LOOP here it comes back around with the HOA.

So, we had built in some contingency funding, but as costs go up over time, it was not enough to cover a change the design plan to haul an unplanned amount of material offsite. So, the project goes on pause. No construction for me in 2019.

We go through a period of problem solving—what are our options for disposing of this material? Where can we get additional project funding? (It turns out that raising funds for this project was not easy to begin with. Many thanks to our steadfast partners at Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission and Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection for their contributions to the project.) We develop an on-site disposal plan. That does not ultimately work out.

It took some time, but fortunately with the support of our amazing local partner, Berks Nature, we were able to secure additional funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Delaware River Program. Whew! Okay, we can get back on track. However, our access point is still through the HOA property. No problem, they told us it would not be an issue as long as we found another disposal option. So I go back to the HOA. Crickets. For months. And months.

This is why you need good partners and contractors. Flyway told me they would figure out how to access the dam from the “hard side.” They did it too.

Finally, June 2022, construction begins. I can’t even allow myself to celebrate. I am waiting for the other shoe to drop. (Other people: “Are you excited?” Me: “Perhaps? <nervous laugh>”.) At American Rivers, we share “WOO HOOs” amongst our staff. I cannot WOO HOO this yet.

A good chunk of the dam is removed. Now, this project was permitted with a passive sediment management approach, which means that everyone anticipated that a volume of sediment would be released. These rivers of central PA move lots of sediment. They are dynamic. Dams trap sediment then some amount of it scours out during big storm events. They are not a permanent storage solution. And the volume released at this site can be handled by the downstream river. But the general public often does not know about all of these dynamics.

In the meantime, I am having conversations with Amy Kober who leads our communications team and our partners at Berks Nature about when and how we should share news of the dam removal with the press. (It turns out that Amy has a fascinating history with this dam in a surprising LOOP that goes back generations. Check out her story in The Revelator.)

Y’all, the shoe drops. Or the YouTube video, as it turns out.

From a concerned fisherman. Not that I blame him. The outreach for the project was done years before it actually happened (because delays). Anyway, someone saw sediment moving down the river and got very upset and made a video about it.

The video starts flying through the dam removal community in Pennsylvania. PA Department of Environmental Protection is not happy. We must initiate a change of plans. The ghosts of the Kehm Dam project are coming back to haunt me.

We can’t let all of this sediment go downstream. What are we going to do about it? Initiate problem solving mode. Gather the brains together—engineers from Inter-Fluve (the original designer), Kleinschmidt (the construction monitoring firm), Flyway Excavating (the implementors), and me (oy…).

We talk through possible options at the site. It turns out that the additional fundraising I did will come in handy (those lemons turn into lemonade when you least expect it). We develop a plan of action. We decide to haul some of the sediment off-site. We employ additional erosion protection measures along the bank. We adjust some of our other previous plans that no longer seem to make sense for the site. We find some bedrock (yay! We love bedrock. Very stable.).

One more hurdle though. There is a closure window for in-stream work that starts on October 1. It is nearly October 1. We reach out to the PA Fish and Boat Commission and request a waiver to work during October. The Commission agrees that it would be better to do additional work now than wait until next year, as it is early in the closure window and impact to fish should be minimal compared to benefits, so they grant the waiver. (Whew!)

October 17. The second phase of construction work is done. The site is evolving nicely. The river is adapting to its new normal as we expect it to. Unfortunately, I can’t see the finished product yet as I am having a back problem. This is why it is great to have good contractors.

So, we finally made it. It’s still rough looking, but once it fills in with plants, it will be a beautiful free-flowing stream once again.

By the way, the dam owner, Rob Marella, was very patient over the course of these many years. For that I am grateful. I hope to see his vision of a revitalized mill restaurant come together.

Now we see what happens over the next few months and meet back in 2023 to see if any additional work needs to be done.

Lessons Learned

While I have taken much away from this project, I want to highlight a few key lessons learned:

- Always plan for the unexpected. You never know what unanticipated issues might arise, so build contingency funding into your grant proposals. Costs are constantly rising as well, so this is critical. Then when the unexpected happens— don’t panic. Just start working through your options to address the hurdle.

- Have a confident project team. Being able to trust your team in times of challenge really helps to alleviate anxiety and stress. You are not an island and you do not need to know everything in order to manage a dam removal project. Good leaders know what they don’t know and find people who do.

- Community outreach is essential. People are more comfortable when they can put a face with a project. Ultimately, awareness of the concerns of the community will allow you to prepare accordingly, even if you cannot avoid opposition to the project.

- Don’t give up. Sometimes these projects can take a long time to move from concept to reality. It is important to keep chugging over and through the hurdles. It takes patience.

- Sediment is a thing. There are a myriad of opinions on sediment in rivers and what is good/bad/negligible. For better or worse, Pennsylvania is on the hot seat in the Chesapeake Bay (and to a lesser degree Delaware River) region for issues involving sediment. If there is sediment behind a dam, which there is in many cases in this region, there will need to be conversations about how to handle it.

It’s been a wild ride. More than anything, I appreciate the good partners that we have who help us accomplish this work. A solid team is essential. Without them, it wouldn’t happen.

Election Day 2022 has come and gone. Today our team at American Rivers went to work to protect rivers, just like yesterday – and just like we will tomorrow.

We are a nonpartisan, practical organization full of individuals who work with anyone interested in advancing policies and projects for healthy rivers and healthy people. Practical is the word that rings the loudest today.

This election season defied a lot of predictions. The President’s party loses on average 26 seats in the midterms for the U.S. House of Representatives. Further, global inflation has demonstrated voters’ resounding rejection of incumbents repeatedly in 2022. So, the odds were in favor of Republicans easily winning the already slimly Democratic-held U.S. House and U.S. Senate.

As of this writing, Democrats are expected to have their best midterm with a Democrat in the White House since 1950 and the Republicans will likely take the House, and still could make a play for the Senate.

In the House, Republicans flipped eight previously held Democratic seats (FL-7, FL-13, GA-6, NJ-7, TN-5, TX-15, VA2, and WI-3) and are leading in eight others (AZ-2, IA-3, MI-10, NY-3, NY-4, NY-17, NY-19, OR-5). Democrats flipped six Republican seats (IL-13, MI-3, NM-2, NC-13, OH-1, TX-34) with leads in four others (AZ-1, CA-41, CO-8, WA-3).

The Senate now stands at 48 Democrats to 48 Republicans with three races yet to be called in Arizona, Georgia (where we expect a December run-off), and Nevada.

So, the bottom line is we don’t know who will govern each chamber of Congress at this moment, but no one can legitimately claim a national mandate or broad support from voters.

And I think that uncertainty is a message in and of itself. The American people aren’t really thrilled with either party. The rhetoric has driven leaders away from addressing the most pressing issues – including climate change, injustices, and loss of nature — towards scoring political points.

Here is the reality that I think most everyone sees:

CLIMATE CHANGE: Extreme weather is happening more often as climate change settles in. According to the U.S. EPA:

- Nine of the top ten warmest years on record have occurred since 1998,

- Heat waves are occurring three times more often than they did in the 1960s,

- A higher percentage of precipitation in the US has come in the form of intense single-day events. Nationwide, nine of the top ten years for extreme one-day precipitation events have occurred since 1996.

- Floods have generally become larger across parts of the Northeast and Midwest and smaller in the West, southern Appalachia, and northern Michigan. Large floods have become more frequent across the Northeast, Pacific Northwest, and parts of the northern Great Plains, and less frequent in the Southwest and the Rockies.

In my home region of Appalachia, we have seen deadly flooding becoming a greater risk every year with a combination of climate change, mountainous topography, and economic decline that has come about as people failed to transition away from coal as it became less competitive.

PERMANENT DROUGHT: Lake Mead and Lake Powell – which together release two trillion gallons of water to cities and farms each year – are at their lowest point since the dams were built. The federal government just issued a warning to the seven states (CA, CO, UT, WY, NM, NV, and AZ) that they will consider changing the way water is released unless the states can agree to a reasonable plan to deal with this reality. Failure to find an agreement has severe implications to the millions who depend on those reservoirs for drinking water, the millions who depend on the hydropower for energy, not to mention all who depend on those farms for their food. It threatens species, water affordability, and some of our most iconic places, like the Grand Canyon.

The solutions aren’t easy and that is why American Rivers will work with our political leaders to try to reduce the rhetoric and work together to find a real path forward.

WILD FIRE: According to National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration, “Research shows that changes in climate create warmer, drier conditions, leading to longer and more active fire seasons. Increases in temperatures and the thirst of the atmosphere due to human-caused climate change have increased aridity of forest fuels during the fire season.”

We know river health starts with forest heath. Uncharacteristically intense wildfires can change the course a river takes, erode its banks, disrupt biological processes, and fill reservoirs with excess nutrients and sediment. More intense fires endanger our rivers and water.

We need decision-makers who are willing to work together to find scientifically based solutions and this is what American Rivers will continue championing. We need our leaders to end the rhetoric and start to work together to find a real path forward.

Last night, voters sent a message to Congress that they need political leaders to work together to address the real issues that are impacting our lives. They want leaders to be thoughtful about our future and get to work.

Now, back to the practical work of American Rivers.

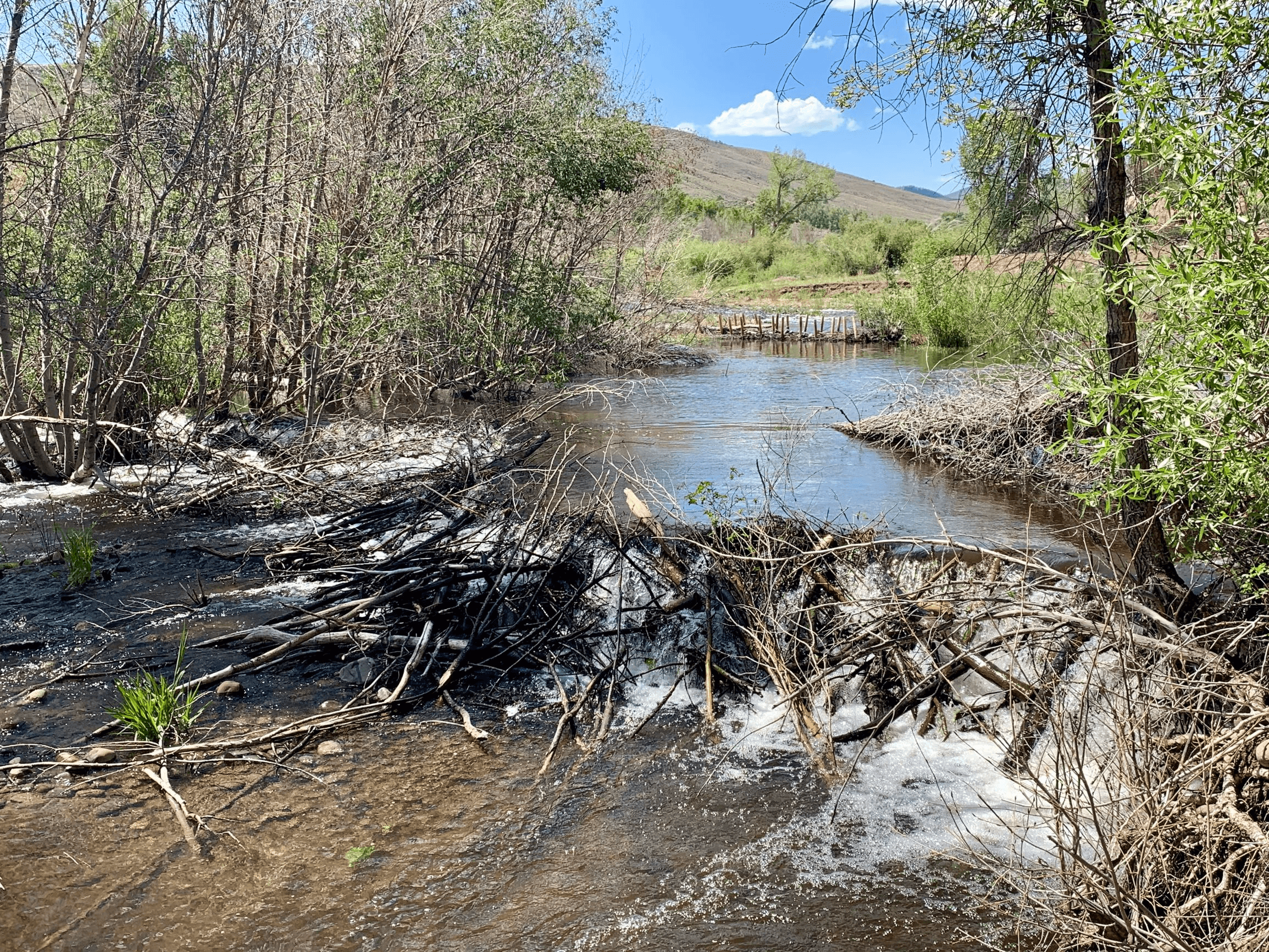

As western mountain snowpacks diminish and wildfires race across parched landscapes, appreciation has grown for the moist mountain meadows and wetlands that hold water up high, feeding streams throughout the summer and providing fire-resistant refuges for wildlife. Before beavers and their dams were largely eliminated by the fur trade, these natural water storage features and refuges were common across western states’ mountain landscapes.

The removal of beavers and other land disturbances have led many creeks to cut deeper into their valleys and detach from their floodplains, dropping the water table and drying out the landscape. A growing field of stream restoration, known as low-tech process-based restoration (LTPBR), seeks to reverse these changes through methods that mimic beaver activity in hopes of enticing them to return.

Projects across the west have demonstrated the benefits of LTPBR on the landscape. Projects have improved water quality, provided important habitat, trapped sediment, increased riparian vegetation and forage, and bolstered resilience against drought, fire, and floods. These benefits are achieved by installing low-tech, hand-built structures, creating “speedbumbs” that enable water from snowmelt and storms to spread across the riparian area, slowing peak flows and recharging groundwater. The rewetted soil “sponge” supports healthy riparian vegetation and reduces wildfire risks.

As LTPBR projects have proliferated across western states, both excitement about their benefits and questions about potential impacts have grown. A new report from American Rivers reviews the published science and case study information on LTPBR to better understand the full range of benefits these projects can provide, and provides scientific evidence to address potential concerns. The report finds ample evidence for LTPBR benefiting habitat and buffering the impacts of droughts, floods, and wildfires, but concludes that more research is needed to better understand the full suite of ecosystem service benefits. It also provides insights on how to address human and social factors related to LTPBR projects, such as mitigating beaver dam impacts to infrastructure.

Click here for full report

CLICK HERE FOR STATE OF SCIENCE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

From Portland, Oregon to Bucksport, South Carolina, communities have been creatively addressing flooding issues by seeking nature-based solutions. For the Gullah Geechee community of Bucksport in South Carolina, rain gardens will empower the community to manage water on properties that are prone to flooding nuisance.

Bucksport is situated in the southern portion of Horry County, at the confluence of the Waccamaw and Pee Dee rivers, adjacent to the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge and just a short thirty-minute drive from the popular tourist destination of Myrtle Beach. The community has an extensive cultural history. In the 18th century, the area, identified as the “Great Bluff” on many topographical maps, was possibly the location of where trade was conducted with the Waccamaw and Pee Dee people at nearby Bull Creek. Burroughs, John Benjamin, “In Search of Uauenee (or the Great Bluff)” (2005). HCAC Research.1.

Bucksport’s recent history lends to an earlier colonial period of timber mills and trade along the river, with the production of the lumber that was used for building homes and businesses throughout Horry and Georgetown counties, as well as ships that were built and then launched from the thriving Bucksport Marina. These booming industries were buttressed by the labor of enslaved people – Indigenous, African and African Americans whose descendants continue to reside in Bucksport and throughout the region.

Today, the community of Bucksport is made up of families that have lived in the area for generations. For many, their way of life is rooted in their connection to family, land and local rivers through long-held traditions such as fishing, gardening and farming. Like many Gullah Geechee communities, that way of life is under threat from unbridled development, political disenfranchisement, economic exclusion, and the many vulnerabilities associated with heirs’ property. Persistent flooding in the community has both exposed and exacerbated these issues.

Over the last 6 years, the community of Bucksport has experienced five major flood events and many smaller flooding issues. Two of those events were caused by riverine flooding related to Hurricane Matthew in October of 2016 and Hurricane Florence in September of 2018. Flooding is also linked to heavy rainfall during the winter months that contributes to rising water levels in the Waccamaw River. Many residents have suffered repetitive damage to their homes and other property, even as the cost of flood insurance has increased almost ten-fold. Additionally, the issue of heirs’ property has historically created a limitation on access to assistance for a declared disaster. This has only recently changed in 2021, with FEMA allowing for heirs’ property owners to provide additional documentation to prove ownership; a crucial step in getting disaster assistance to historically black communities. Post and Courier-Hurricane Wire.

In June 2021, the Association for the Betterment of Bucksport partnered with American Rivers to form the Bucksport Community Partnership, a collaboration comprised of non-profit organizations, universities and governmental agencies dedicated to supporting residents’ efforts to find equitable, holistic and nature-based solutions to flooding and the variety of other issues that have created social, economic and ecological vulnerabilities for the community. The Partnership wasted no time getting to work. Guided and motivated by the thoughtful leadership of Bucksport residents, the Partnership completed a sustainability assessment and a community flood assessment with a user-friendly story map. It also supported residents’ advocacy work, quest to bring attention to their story in local media (see this link; and here), and successful efforts to secure funds from the American Rescue Plan Act to implement a project focused on cultural preservation and economic development.

On June 4th, 2022, the Partnership held a community rain garden event. Rain gardens are gardens planted with grasses, flowers and other plants that collect rainwater from driveways, roofs and streets and allow the water to soak into the ground. Rain gardens not only minimize nuisance flooding, but they also beautify the landscape and filter pollutants from rainwater before it flows into rivers and streams. The event took several months of planning as partners collaborated with staff from the Clemson University Extension Master Rain Gardener Program and Horry County Parks and Recreation Department to identify soil composition, native and culturally significant plant species, and location options for two gardens to be installed at the James R. Frazier Center, a community center located in the heart of the Bucksport community. The Partnership engaged community members in voting on the potential locations for the gardens, with the final vote identifying the two sites near the community center’s picnic shelter and parking lot where rainwater could be captured. The locations along with educational signage would also be accessible to visitors and visible from the roadway. The sites were prepared before the event to avoid a lengthy installation that would continue into the hottest part of the day. Staff members from the Horry County Parks and Recreation Department staff excavated the sites. The Association for the Betterment of Bucksport, American Rivers and partners from Clemson University Extension and Coastal Conservation League worked together to purchase and transport compost, mulch, sand, and plants to the community center.

On the day of the event, Bucksport resident Kevin Mishoe, along with partners, briefly shared stories about how the project was conceived, their participation in the project and plans to offer a Master Rain Gardener class for residents through Clemson University Extension. Dan Hitchcock, with Clemson University Extension, gave an outline of the rain garden installation process with Ashley Cowan from Horry County Parks and Recreation describing the benefits of rain gardens for flood mitigation.

Following the presentation, residents and partners worked together to install the plants in the rain gardens.

Installations were finished by late morning just before the heat of the summer day made the work too exhausting.

The installation was topped off by a catered lunch that included an array of southern foods, like fried chicken, pulled pork, stewed corn, baked beans, slaw, and fresh fruits. Horry County Council Member, Orton Bellamy, attended the lunch and noted the success of the rain garden installation, engaging with community members and partners throughout the meal. To determine interest in attending a Master Rain Gardener class, American Rivers provided a sign-up sheet for community members. As more residents arrived the list began to fill up. Residents who signed up for the class were given a raffle ticket. The winners were awarded a waterproof map of the Waccamaw River Blue Trail. Within the map, pages 25 and 26 offer images of the Waccamaw River which passes through the Bucksport community.

The community rain garden event marked the first step in empowering residents to manage the water that flows to their properties. While the rain gardens will not reduce the impacts of severe flooding, they will absorb runoff from light and moderate rainfall events that result in nuisance flooding and standing water. The Partnership is currently planning a large and ambitious restoration project for the community that will mitigate severe flooding, enhance the area’s natural character, and promote economic growth and cultural preservation.

The next step of Partnership’s rain garden initiative will ensure that residents can install rain gardens on their properties. The Association for the Betterment of Bucksport and American Rivers have collaborated with Clemson University Extension and Horry-Georgetown Technical College to bring the Master Rain Gardener Program to Bucksport so that residents have the opportunity to learn how to install and maintain rain gardens on their own properties. Additionally, since the program is offered as an online course, American Rivers will be bringing a Certified Master Rain Garden installer to provide further hands-on demonstrations during installs for some of the senior residents in the Spring of 2023.

As Hurricane Ian recently impacted the Coastal region of northern South Carolina excessive rain allowed for the rain gardens to be tested. Fortunately, flooding was not as much of an issue as it has been with past flood events. The image below offers a glimpse at the effectiveness of how using rain gardens help to mitigate flooding.

Midterm elections can create obstacles or open opportunities for clean water and healthy rivers. They often give the party in power the advantage and ability to set the congressional agenda including substantive policy matters, fiscal spending priorities, and nominations for key agencies.

Midterms are a Referendum on the President’s Performance

Every two years, our nation holds Congressional elections. The election that occurs two years after a presidential election is known as the midterms and is a referendum on the president’s performance. The midterms are where voters get to decide who serves in Congress and is a primary indicator of the public’s approval of the incumbent president. Biden’s latest job approval rating of 42 percent is a slight improvement from his 38 percent low in July. Historically, the president’s party loses ground in the midterms.

In 2022, all 435 seats in the House are up for grabs as well as 35 Senate seats. However, public attitudes about environmental protections in the Clean Water Act, for example, remain resiliently strong with 75 percent in favor of protecting more waters and wetlands.

Since taking office, the Biden-Harris Administration has led the Democratic Party holding power in House and Senate. Their administration has made climate and environmental justice a priority. The majorities in both chambers, although marginally thin (220-212), created significant victories such as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), a historic law dedicated to rebuilding our nation’s crumbling infrastructure system, and the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), a transformative climate tax law in clean energy.

Taken together, both the BIL and IRA restores and reaffirms our nation’s commitment to fighting climate change, improving the health of our waterways, enhancing water quality, increasing access to clean water, and advancing environmental justice for all.

Key Races to Watch

Earlier this year, nearly 30 Democratic House members announced they would not seek reelection which makes the House all that more important. A pickup of only five seats would transfer control of the chamber to Republicans. The Senate is split 50:50 and the election is a toss-up. There is a slight chance Republicans can overtake the chamber. Below are some key races we are watching.

The House

- Ohio’s 9th: Rep. Kaptur (D)

- 2020 Results: Biden 47.7– Trump 50.6

- What to Watch: Leans Republican +3 points. She is one of the longest serving lawmakers and is Co-Chair of the House Great Lakes Task Force. Has led several bipartisan efforts to address algae blooms and raw sewage dumping in Lake Erie.

- 2020 Results: Biden 47.7– Trump 50.6

- Michigan’s 7th: Rep. Slotkin (D)

- 2020 Results: Biden 49.6 – Trump 48.7

- What to Watch: Leans Republican +2 points. Over the last few years, she has played an instrumental role in helping the Department of Defense with PFAS cleanup efforts – toxic chemicals contaminating water resources and impacting the health of servicemembers.

- 2020 Results: Biden 49.6 – Trump 48.7

- Virginia’s 7th: Rep. Spanberger (D)

- 2020 Results: Biden 52.4 – Trump 45.7

- What to Watch: Leans Democrat +1 point. A member of the Sustainable Energy and Environment Coalition in the House, she has actively worked to upgrade water treatment plants and reduce energy costs for farmers.

- 2020 Results: Biden 52.4 – Trump 45.7

The Senate

- Arizona: Sen. Kelly (D)

- 2020 Results: Biden 49.36 – Trump 49.06

- What to Watch: Toss-up. He has negotiated and secured $4 billion in the IRA for drought mitigation and called on Interior to outline comprehensive actions to compel a Basin-wide agreement for the Colorado River system.

- 2020 Results: Biden 49.36 – Trump 49.06

- Georgia: Sen. Warnock (D)

- 2020 Results: Biden 49.5 – Trump 49.3

- What to Watch: Toss-up. Has made climate and environmental justice part of his platform. Advocated to protect the Okefenokee Swamp from a proposed titanium mining operation which would have impacted freshwater resources including fish and wildlife.

- 2020 Results: Biden 49.5 – Trump 49.3

- North Carolina: Rep. Ted Budd (R)

- 2020 Results: Biden 49.9 – Trump 48.5

- What to Watch: Leans Republican +2 points. Supports building more pipelines and less regulation specifically on the Clean Water Act’s definition of “waters of the United States”.

- 2020 Results: Biden 49.9 – Trump 48.5

Three Most Likely Midterm Election Result Scenarios:

American Rivers anticipates three main scenarios impacting the legislative activity and congressional action on our federal priorities.

1 – Republican House, Democratic Senate

Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) will likely become speaker in January if Republicans retake the House. The GOP intends to jam up the legislative process by prioritizing and launching investigations into the Biden Administration. Under this scenario, we can expect legislative action to stop or slow down outside must-pass funding bills. If this happened, we would likely see a prolonged lame duck in November and December to accomplish legislative victories remaining for the Biden-Harris Administration.

2 – Republican House, Republican Senate